The COVID-19 pandemic and the global reverberations of the war in Ukraine have unleashed a number of socioeconomic, security, political and geopolitical shocks and shifts in North Africa. These changes are driving uncertainties but could also create opportunities across the region.

To what extent is the uncertain economic outlook reshaping regional geopolitics? How are governments responding to current challenges and what potential impacts might arise amid crises? What role can civil society play within countries in domestic turmoil, and what are the obstacles to innovation in North Africa? And how have the region’s international relations evolved in recent years and months?

In a joint effort by the Elcano Royal Institute, the Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI) and the Middle East Institute (MEI), this Dossier seeks to unlock the nuances and details of North Africa’s unfolding dynamics, while contextualising them in the broader geopolitical scenario.

- 1. The Ukraine War’s Economic Impact on North Africa: Winners, Losers, and a Dangerous Lack of Long-Term Vision

- 2. Up in the Air: A Call for Climate Collaboration in North Africa

- 3. Jihadism in North Africa: A ‘Resilient’ Threat in Times of Global Crises

- 4. In Tunisia, Civil Society Is Back in the Trenches

- 5. In North Africa, Startups and NGOs Drive Local Innovation. What Is Missing?

- 6. The Maghreb: Regional Disintegration and the Risks of the Zero-Sum Logic

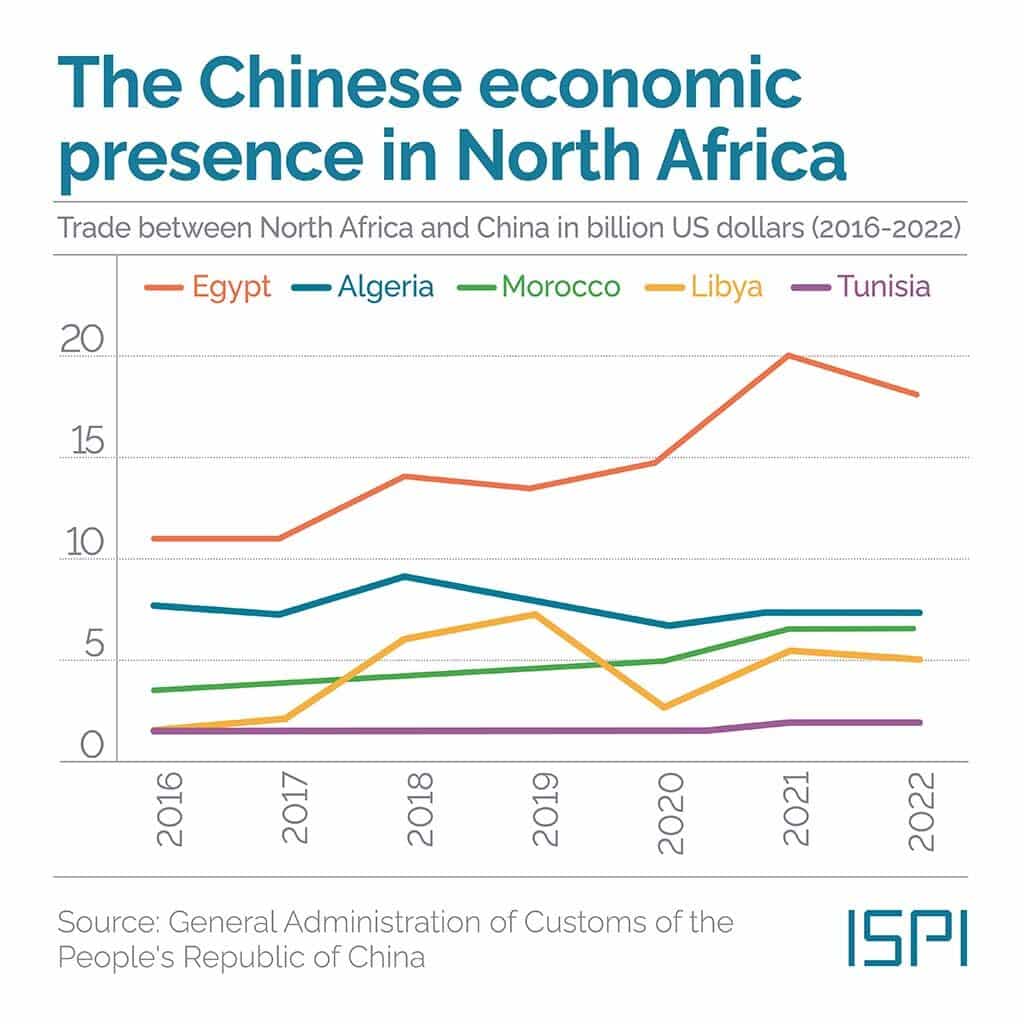

- 7. Shifting Balances in the MENA Region: Russia and China No Longer Behind the Scenes

The Ukraine War’s Economic Impact on North Africa: Winners, Losers, and a Dangerous Lack of Long-Term Vision

Riccardo Fabiani, Project Director, North Africa, International Crisis Group | @ricfabiani

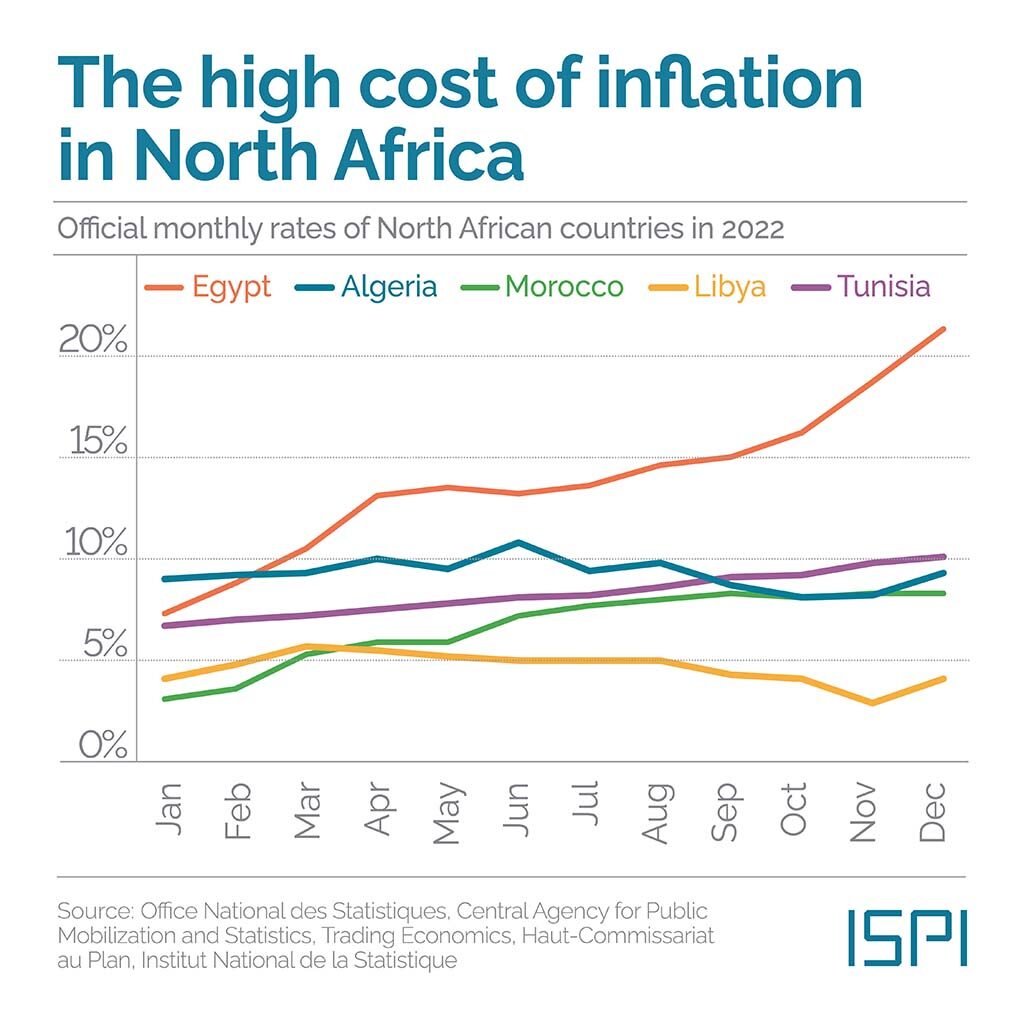

The Ukraine war’s dramatic impact on commodity prices and the global monetary tightening has reshaped the regional political and economic balance. This reshuffling has rewarded big hydrocarbon exporters, such as Algeria and Libya, and exacerbated tensions in energy-dependent Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco. While the former have taken advantage of this windfall both economically and politically, the latter have had to turn to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for help because of their fast-deteriorating outlook. But the politics of financial support for Cairo and Tunis has been challenging, exposing these countries’ unresolved political and economic dilemmas.

While this economic reshuffling has strengthened hydrocarbon producers and further exposed energy importers’ pre-existing tensions, the long-term political and economic outlook for all these countries remains dim. Higher oil and gas revenues contributed to Algeria’s assertive and proactive foreign policy and shored up a temporary lull within Libya. Meanwhile, reeling from a lost decade of stagnation and instability, and having lost their external economic rents, Egypt and Tunisia are struggling to identify a new political and economic model. But regardless of their current situation, in the long term, all of these countries will continue to grapple with the lack of a credible development vision. As local ruling elites resort to an increasingly nationalist stance to deflect socio-economic pressure, the potential repercussions of this strategy risk fuelling a cycle of stagnation and instability in the region.

Economic winners and losers in North Africa

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the worldwide rise in commodity prices provided a boon for North Africa’s hydrocarbon producers, exacerbating the traditional economic divide between net energy exporters and importers in the region. Over the first six months of the conflict, Brent prices rapidly exceeded USD100 per barrel, and Dutch TTF gas prices tripled. Algeria and Libya benefited from this windfall as European governments scrambled to find alternatives to Russia’s increasingly politicised oil and gas supplies. Algiers has received a long series of official visits by European officials interested in strengthening diplomatic ties and securing additional gas volumes over the past year. In January 2023, even its more unstable neighbour, Libya, landed an USD8 billion deal with Italian oil company ENI to increase hydrocarbon supplies, despite the country’s persistent divisions.

The sudden jump in hydrocarbon revenues mitigated the impact of high imported food prices, despite these two countries’ insufficient agricultural production. Growing export receipts and the first current account surplus since 2013 enabled Algeria’s dinar to strengthen, reducing the impact of increasing commodity prices for the overall population. In addition, the authorities introduced a raft of measures to support incomes and agricultural production. In Libya, the persistent division of its institutions meant that while hydrocarbon revenues went up, shoring up the current and fiscal accounts, the dispute between the Tripoli government and the Tobruq-based parliament made it impossible to approve a budget. Despite this, the internationally-recognised executive still financed wages and subsidies by spending what was authorised in the previous budget each month.

The global monetary tightening that followed the rise in inflation left the region’s hydrocarbon producers unaffected, because of their low external debt levels. The U.S. Federal Reserve gradually hiked its rate from 0.25% in March 2022 to 5% in March 2023 in an attempt to tame growing inflation. These tightening liquidity conditions had almost no impact on Algeria and Libya. The IMF projected Algeria’s government debt to fall from 62.8% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2021 to 52.4% in 2022, on the back of higher budget revenues and economic growth. Additionally, the debt stock is almost entirely domestically-held, dinar-denominated, and around half of it is in the hands of the central bank, shielding Algeria from the vagaries of the international markets. While Libya’s total debt levels are higher (estimated at 83% of GDP at the end of 2021), all its liabilities are held domestically and denominated in the local currency.

In sharp contrast, the energy importers in the region were hit hard by the combination of the negative terms-of-trade shock and interest rate hikes. Egypt and Tunisia, which are still reeling from a decade of political instability and anaemic growth, felt the brunt of it, while Morocco benefited from a more orderly domestic context and a cautious fiscal stance.

In early 2022 Egypt’s import bill exploded, due to the country’s heavy reliance on purchasing fuel products and cereals from the international markets, leading to a depletion of foreign reserves. Financial investors began to doubt Cairo’s ability to defend the managed exchange rate, causing them to withdraw their money and forcing the central bank to deplete even more hard currency to prop up the exchange rate. By July 2022, reserves’ cover dropped to around three months of imports in July 2022, down from 6.8 months the previous year. As a result, the authorities had to raise interest rates and eventually let the exchange rate depreciate twice in 2022 and again earlier this year. The higher interest rates and currency depreciation fuelled an increase in debt servicing costs, which the IMF expects to exceed 33% of total budget expenditures in fiscal year 2022/23.

Similarly, Tunisia’s current account deficit widened from 6.2% of GDP in 2021 to 9.8% in 2022 due to the rising import bill. Likewise, the fiscal deficit was expected to hit 8.8% of GDP in 2022 (from 7.7% the year before) and external debt levels were close to 90% of GDP at the end of 2022. While Tunisia still managed to secure around USD900 million of external financing in 2022 from Algeria and Afreximbank, its considerable external debt repayments scheduled for 2023 and 2024 (equivalent to USD2 billion and USD2.6 billion, respectively) mean that the authorities are under enormous pressure to reduce these deficits and find additional foreign funding to avoid bankruptcy.

Finally, Morocco faced the same double whammy of rising commodity prices and rising interest rates, but from a more solid position. In 2022, the current account deficit worsened to a projected 4.3% of GDP, up from 2.3% the year before, due to higher food and fuel prices and the negative impact of a drought that undermined agricultural production. Yet, foreign reserves’ import cover remained fairly comfortable at 5.5 months, only slightly down from 5.8 in 2021, and external debt levels were contained at around 40% of GDP, thanks to Rabat’s prudent fiscal stance.

The challenging politics of external financing

Faced with challenging economic conditions, the energy-poor countries turned to the IMF and Gulf countries for assistance, but the unfolding and outcome of these negotiations varied considerably. Egypt initially tried to negotiate financial support from its Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) partners and a loan of USD5-7 billion with the IMF, but the complex negotiations with both interlocutors forced Cairo to accept a smaller loan from the Washington-based institution and more stringent conditions from the GCC. Tunisia was in talks with the IMF for months to no avail, due to President Kais Saied’s reluctance to commit political capital to an unpopular reform package and the subsequent considerable disagreement within the international community on the best way forward. His authoritarian stance also contributed to making these talks difficult. In contrast with these experiences, Morocco capitalised on its relatively stable political and economic outlook to secure a more flexible credit arrangement.

Egypt

The agreement between the IMF and Egypt relies significantly on other international and regional partners’ financial contribution to plug Cairo’s external economic deficit. The government initially requested a much larger loan of USD5-7 billion but was unable to agree with the IMF on loan conditions. In December 2022, Egypt secured a 46-month loan equivalent to USD3 billion, to be supplemented by an additional USD14 billion from international financial institutions and regional partners. In particular, the IMF anticipates that the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members will contribute USD10 billion in public sector asset purchases and roll over USD28 billion in deposits with Egypt’s central bank.

The IMF deal attempts to tackle some of these issues by promoting private sector activity but is likely to meet resistance by affected interest groups in the army. Its reforms include a commitment by the authorities to slow the implementation of state-funded projects and an explicit presidential endorsement for one of the potentially most difficult measures to implement: the state divestment policy. The goal of this measure is to decrease the role of the government and military in the economy, enabling the private sector to take charge and attract foreign investment. Following President Abdelfattah al-Sisi’s ascent to power in 2013, the government relied on foreign financing to implement a range of infrastructure projects to boost the economy. The government gave military-owned enterprises preference to execute this plan, leading to their prominence in several sectors and a decrease in influence for crony capitalists previously associated with President Hosni Mubarak and other private businesses. Sisi now faces a delicate balancing act between managing army factions and pressure from the IMF, tempting him to water down these reforms as much as possible to avoid a potentially destabilising domestic backlash.

The Gulf’s more cautious stance on external lending is likely to further limit Cairo’s room for manoeuvre. Unlike previous crises, GCC states now demand public assets as guarantees for their financial aid. After 2013, Saudi Arabia and the UAE provided generous funding to Egypt to bolster political stability, viewing Sisi as a bulwark against the perceived Islamist threat in the region. But their stance has evolved in recent months, leading Gulf sovereign wealth funds to acquire minority stakes in various Egyptian firms instead of providing grants or cheap loans, and resulting in tensions with Cairo over the value of some assets. This change has irritated Egyptian officials and added to pre-existing but concealed geopolitical tensions between Egypt and some of its Gulf partners over the delayed handover of the Red Sea islands of Tiran and Sanafir to Saudi Arabia and their allegedly soft stance vis-à-vis Ethiopia on the dispute over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

Tunisia

The politics of IMF financing are even more complicated for Tunisia, which has not yet secured a loan. In October 2022, the international financial institution unveiled an agreement between its staff and the Tunisian authorities for a 48-month arrangement of USD1.9 billion. The announcement provided a summary of the agreed measures, which included containing the public sector wage bill, reducing subsidy spending, reforming state-owned enterprises, and enhancing competition. However, in December the IMF Executive Board postponed the scheduled meeting to approve this deal, which means negotiations are ongoing.

The IMF is worried about the Tunisian government’s unwillingness to implement some of the necessary reforms, the lack of wider buy-in (particularly from the country’s main trade union, the UGTT), and President Kais Saied’s refusal to publicly endorse these measures. After the October 2022 agreement, the authorities were supposed to gradually increase fuel prices and issue a law on state-owned firms, but neither has yet materialised. The growing polarisation of Tunisian society, repression of civil society and opposition groups, and the unpredictability of the presidency exacerbated this stalemate.

While Tunisia’s external partners agree on the importance of financial support, they seem to diverge over the best approach. Anxious about a possible economic collapse and its potential knock-on effects on migration flows across the Mediterranean, Italy played a proactive role in trying to facilitate a compromise between the IMF and Tunis and securing additional funding. In contrast, the US expressed concern about the country’s democratic backsliding and sent messages that the only way out of the current economic deadlock is to accept the IMF-mandated reforms. Meanwhile, Algeria is reportedly considering a parallel financing package to shield Tunisia from the international institution’s perceived “blackmailing”.

Morocco

In comparison to Egypt and Tunisia, Morocco benefits from a more stable economic outlook and a relatively uncontroversial relationship with the IMF. In March, Rabat requested a 24-month precautionary credit line equivalent to USD5 billion. The IMF offers this arrangement, with no strict conditionality, to countries with sound economic policy frameworks and a solid track record. Despite its credit rating remaining in “junk” territory since the downgrades that took place in 2020 and 2021, in March, Morocco successfully issued USD2.5 billion bonds on the international financial markets.

The broader political impact of the economic reshuffling

Politically, the region-wide economic rearrangement inevitably strengthened the hydrocarbon exporters, while exposing the pre-existing vulnerabilities in the energy-poor states. Algeria took advantage of this windfall to strengthen its regional influence, while Libya bought a measure of domestic calm thanks to higher oil and gas revenues. On the other hand, Egypt and Tunisia attempted to evade the challenging dilemmas of reform posed by external constraints and their reluctant domestic constituencies.

Algeria’s international standing and more assertive foreign policy benefited from the hydrocarbon windfall. Algiers’ role as a key energy supplier to Europe facilitated a diplomatic rapprochement with France, closer relations with Italy and tighter cooperation with the European Union. The surge in oil and gas revenues fuelled its resolve to regain a more central and proactive foreign policy role, as exemplified by a raft of initiatives taken by Algeria at the African Union, in the Sahel region, and on issues related to Palestine, Western Sahara, and Tunisia. For instance, in February 2023 President Abdelmadjid Tebboune announced a new USD1 billion fund to finance development projects in Africa, which is part of the strategy to reaffirm the country’s centrality on the continent and was only made possible by the comfortable economic position the country found itself in following the economic reshuffling.

Although institutional divisions continued to undermine Libya’s governance, higher hydrocarbon revenues contributed to the country’s recent calm. Between April and May 2022, tensions between West and East-based institutions over the control of oil revenues pushed East-based Field Marshall Khalifa Haftar to blockade hydrocarbon facilities, reducing total exports. This move accelerated the increase in global oil prices, prompting the U.S. and other actors to try to mediate between the two sides. In June, pressure from the U.S. and the UAE enabled a deal between Tripoli-based Prime Minister Abdelhamid Dabaiba and Haftar, leading to the resumption of production and smooth flow of energy exports and earnings. The recycling of these receipts into the licit and illicit economy contributed to Libya’s precarious stability. Over the past nine months, officials and militias from both sides of the conflict refrained from major military operations because they benefitted from the redistribution of this rent. But this arrangement also strengthened the status quo at the expense of international and domestic calls to achieve institutional reunification by organising elections.

In contrast, the new economic conditions exacerbated pre-existing political and economic problems in Egypt and Tunisia, presenting dilemmas for their rulers. Both countries have lost their vital external economic rents (Egypt’s ‘anti-Islamist rent’ provided by the Gulf and Tunisia’s ‘democratic rent’ offered by Western institutions) and are still struggling to identify a suitable economic model to leave behind a lost decade of economic stagnation. The Egyptian government took contradictory steps to address the current crisis: it assigned new land to the army despite its promise to reduce the military’s economic footprint, and its commitment to the IMF agenda is unclear.

In Tunisia, helped by international divergences on how to best deal with this situation, the president continued to evade committing to a deal and its stringent and politically-sensitive conditions. In doing so, he took the country to the brink of default. President Saied failed to offer a convincing alternative vision to a deal with the IMF, as exemplified by his now dead plan to force corrupt businesspeople to repay money gained through bribery under former President Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali’s authoritarian system through investment in deprived areas, and his rhetorical attacks against “speculators” allegedly responsible for shortages and inflation.

Nationalism instead of long-term economic planning

Regardless of this economic rearrangement’s immediate effects, North African governments continue to face daunting prospects for long-term stability and development. Despite the temporary improvement in economic conditions, the region’s oil producers have not yet presented any realistic plan for the ongoing energy transition and the need for diversification. As for energy importers, while they might be able to escape politically destabilising debt defaults, they still lack any credible vision for long-term growth. As a result, in the coming years, North Africa’s winners and losers will continue to face the same, unanswered question: how can the region accelerate its sluggish pace of development?

In the aftermath of a politically chaotic decade, incumbents seem to have given up on any vision for future economic growth and transformation. Still reeling from the negative consequences of the neo-liberal turn of the 1980s and 1990s (cronyism, corruption, underemployment, low investment levels, for example), these countries are experimenting various policy approaches, so far with little success. In Egypt, Sisi side-lined former President Hosni Mubarak’s cronies and tasked the army with running the economy, while financing massive infrastructure projects with external loans. In Algeria, the government jailed or silenced oligarchs associated with the previous president, but it remains unclear whether the government, the local private sector, or foreign investors will replace them as a potential growth engine. In Tunisia, Saied lacks any credible economic plan and seems to underestimate the risks of his brinkmanship with the IMF. A new breed of warlords-turned-businessmen who are profiting from a temporary economic settlement rose in Libya and the country’s reunification remains out of sight. Meanwhile, Morocco stands out only as a partial exception, as the monarchy remains committed to its modestly successful development model, despite the vulnerabilities highlighted by the wave of protests that shook the country between 2016 and 2018.

None of these countries has yet been able to chart a convincing path to political stability and economic development, despite the limited opportunities afforded by the West’s willingness to move parts of its supply chains closer to home. As talk of de-globalisation spreads across Western policy circles and the U.S. and Europe reduce or cut their ties with some of their traditional energy (Russia) and manufacturing (China) suppliers, opportunities arise from the suggestion of “near-shoring” or “friend-shoring” some of their productive capacities – transferring parts of their supply chains to countries geographically and politically closer to home. While this holds great promise for North Africa, the region risks missing this occasion due to its persistent political instability and lack of long-term vision.

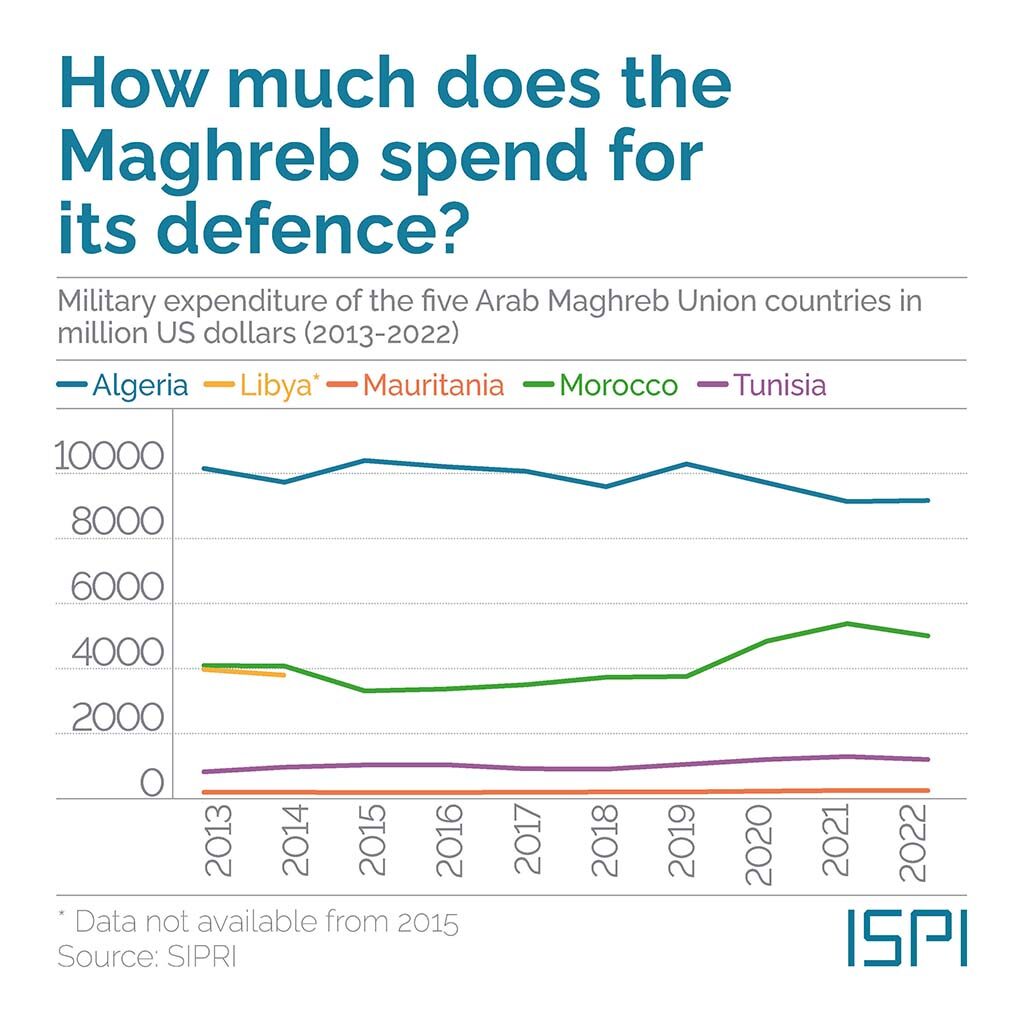

Instead, North African governments filled this vacuum of vision with increasingly nationalist and xenophobic rhetoric. Local governments scapegoat alleged external or internal enemies, and at times even their Western partners, to deflect international pressure and distract domestic constituencies. In Egypt, Sisi used the threat from Islamist groups as an excuse to militarise the country’s political and economic life and extract a generous financial rent from the Gulf. President Saied repeatedly blamed Islamists, the business class, Sub-Saharan Africans and Westerners for Tunisia’s political and economic failures. Finally, Algeria and Morocco are locked in a diplomatic escalation and military arms race as their respective leaderships trade accusations of plotting to undermine each other’s national security and territorial integrity.

This exclusionary nationalist trend risks amplifying a feedback loop of economic stagnation, regional tensions, and instability, with potential repercussions for Western security interests. After a lost decade of political and economic volatility, the hardening rhetoric and targeting of minorities and alleged external enemies threaten to undo the limited progress achieved so far, exacerbating problems of polarisation and migration. In this context, the U.S. and Europe’s short-term pursuit of their energy security and complacent support for the institutional economic adjustment mechanisms enforced by the IMF are insufficient to buttress growth and stability in the long run. It is therefore in their interests to prod local elites into breaking out of their zero-sum mentality and offer a more ambitious long-term development vision to this region.

Up in the Air: A Call for Climate Collaboration in North Africa

Karim Elgendy, Associate Fellow, Environment and Society Programme, Chatham House | @NomadandSettler

The Mediterranean basin, with its unique geography, is poised to become one of the most affected regions by climate change this century. Within this region, North Africa is facing disproportionate risks, not only compared to its share of global population and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) but also relative to its contribution to historic greenhouse gas emissions. The region only represents 2.6% of the global population, and 0.8% of global GDP and is responsible for 1.7% of global carbon emissions.

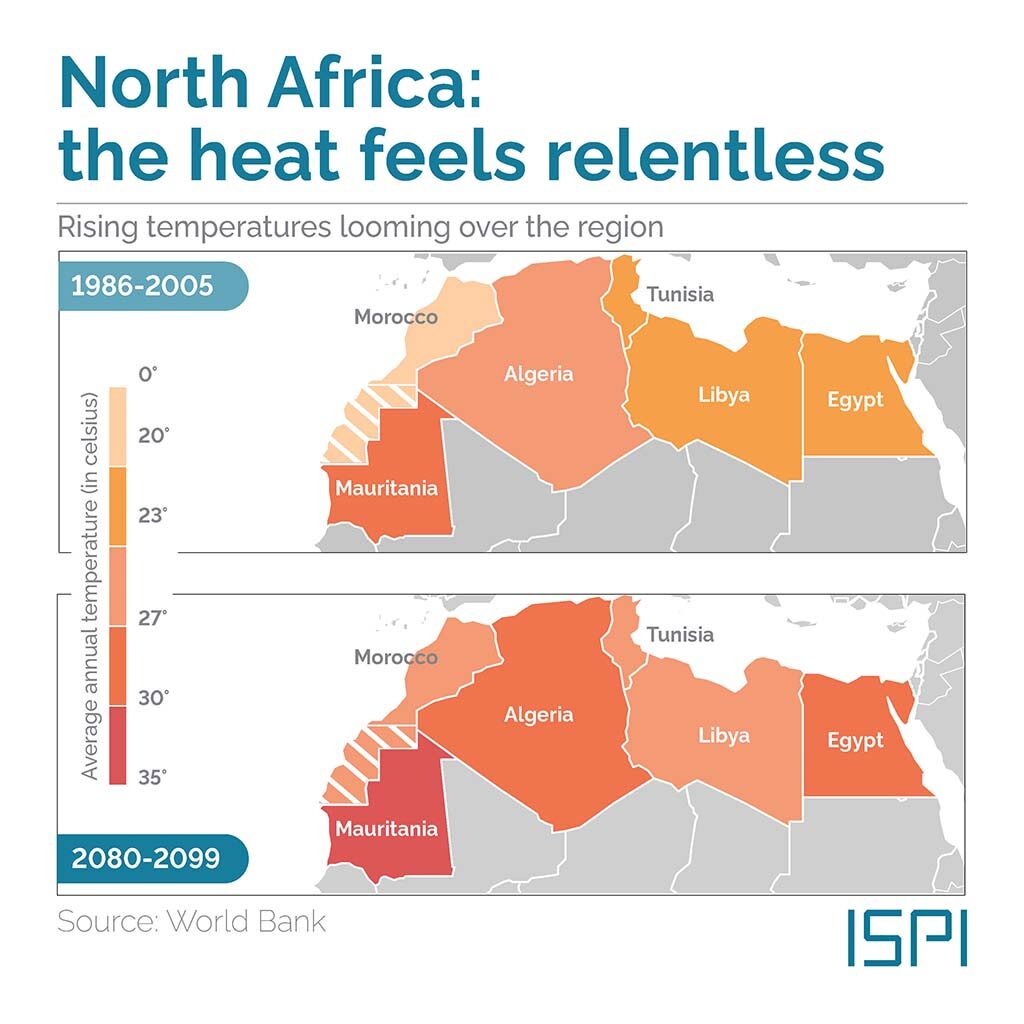

The physical impacts of climate change alone are sufficiently alarming. Average and seasonal surface temperatures have already increased at twice the global rate over most areas in North Africa; and the trend is likely to continue, with average annual surface temperatures projected to increase even faster than the global average under most warming scenarios. The most significant temperature increases are expected to occur in areas nearer to the Mediterranean coast and in inland Algeria.

Against this backdrop, hot days and tropical nights have already become more frequent, and heat waves are expected to become more intense and more frequent even under a 1.5°C of global warming scenario. Marine heat waves off the coasts of North Africa have also doubled in frequency between 1982 and 2016. Children born in North Africa in 2020 will be exposed to four to six times more heat waves during their lifetimes than those born sixty years before.

Changes expected to rainfall changes are more variable but arguably more significant. Average annual rainfall has decreased over most of North Africa since 1960. While in western North Africa, average annual rainfall has recovered or become wetter since 2000 with increases in heavy rainfall and flooding, eastern North Africa has seen a drop in rain days of over 10mm per day and an increase in the number of consecutive dry days.

Looking ahead, North Africa is expected to become arider, and rainfall is likely to become more variable. Average annual rainfall is projected to decrease under global warming scenarios of 2°C and higher. The Atlas Mountains could receive up to 40% less rain and snow under the worst case climate change scenario. Egypt is expected to experience 13% reduction in rainfall under the same scenario, and Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia are expected to become drought hotspots by the end of the century.

Additionally, sea level rise and storm surge present serious risks to North African coasts, especially to the low-lying Nile Delta, 18% of which is already below the mean sea level. In 2010, 2011 and 2015, the Nile Delta coast experienced storm surges of 1.2 metres, almost three times as high as the average. These storm surges caused flooding to the Delta’s lowlands, damaged some coastal structures, and led to seawater intrusion that affected potable groundwater sources. In Egypt, more than 16% of the population lives below 5 metres above sea level, and 30% of the Delta’s fertile agricultural land is at risk from inundation and seawater intrusion. In the absence of any adaptation, Egypt is one of the countries projected to be most affected by future sea level rise – under a 4°C global warming scenario – in terms of the number of people threatened by flooding.

Cascading impacts on key economic sectors

In addition to the primary slow-onset impacts of climate change on the region, secondary impacts on economic sectors such as agriculture and tourism pose a more urgent risk. Climate change is already reducing crop productivity in North Africa. It has slowed agricultural productivity growth in Africa by 34% since the 1960s, the highest impact of any world region.

Reduced rainfall and decreased availability of ground water to bridge drought years (as a result of declining rainfall and groundwater depletion due to overuse and mismanagement), together with increased temperatures and shifts in the growing season are expected to diminish agricultural productivity. In addition, the combination of high temperatures and high relative humidity can be especially dangerous for livestock and has already decreased dairy production in Tunisia.

According to research focusing on the wider Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, a 1% increase in temperature during winter would result in a 1.12% decrease in agricultural production. Coupled with the increasing demand for water and food due to population growth across North Africa, such a reduction in productivity is expected to impact food security adversely. As the region comes to be more dependent on food imports, it will become increasingly at the mercy of global shortages, price shocks, and increasing disruptions.

With the regional economy and livelihoods highly dependent on agriculture, economic development and employment become more at risk. Agriculture is a key sector across North Africa, employing almost 33% and 21% of Morocco and Egypt’s populations, respectively, as well as 16%, 14% and 10% of Libya, Tunisia, and Algeria’s populations, respectively. In addition, the share of agriculture in the national (GDP) of the region (with the exception of Libya) ranges between 10% and 13%.

The region’s tourism sector is also expected to be negatively impacted by climate change. Both hotter summer conditions and reduced water availability could reduce tourism flows to its coastal destinations. In Egypt, damage to tourism due to coral bleaching alone might result in a loss of USD6.4 billion in income annually by 2060.

Besides, job losses in agriculture and tourism will likely lead to urban migration in search of city jobs. North Africa is already Africa’s most urbanised region, with 56% of the region’s population currently living in urban areas. A surge in urban migration could cause higher urban unemployment as new migrants lack the skills required for urban jobs. Increased urban populations could also result in higher demand for municipal services that outstrips municipal capacity, potentially resulting in mounting social tensions.

Climate impact intersections

Like the rest of the African continent, climate change impacts in North Africa intersect with non-climate factors such as difficult socioeconomic conditions, political instability, resource competition, livelihood changes, and vulnerabilities among different social groups. The negative effects of climate change within these intersections can act as a threat multiplier. Its uneven consequences might align with existing rifts between communities, exacerbating grievances and socioeconomic tensions and fuelling political discontent and unrest. Such tensions, coupled with the deterioration of living conditions, could also provide recruitment opportunities for terrorist organisations.

Hence, these secondary climate change impacts correlate with conflict, instability and violence. Growing evidence links rising temperatures and drought to conflict risk in Africa. Increased livestock mortality and livestock price shocks in Africa were potential factors in localised conflicts between pastoralists and farmers. However, no direct causal link has been established between climate change and violent conflicts. Additional factors (such as a political ideology) are indeed needed for armed violence to erupt. Despite ongoing water scarcity in the MENA region, the incidents associated with resource competition spilling over into conflict were limited. In fact, the historical record shows that the water-scarce MENA region has experienced more instances of water cooperation than water conflict.

These intersectional risks are most visible in cities where residents – especially those living in coastal or low-lying areas or in informal housing – are exposed to multiple climate hazards (such as floods, extreme heat and sea level rise) while also experiencing poverty, insecure jobs, and unsafe housing.

Regional response

Given the risks above, the region’s limited historical emissions, and its low carbon emissions per capita, much of climate action in North Africa has focused more on climate change adaptation (e.g. Morocco’s water conservation projects funded by the Green Climate Fund) and less on climate change mitigation – unless an economic co-benefit could be achieved. Yet owing to their lack of technical and financial abilities to adjust to changing environmental and economic conditions, North Africa’s countries have a limited adaptive capacity to address and adjust to these primary and secondary impacts.

This adaptive capacity varies between the regional countries depending on governance models, business environments, and the equitability of resource distribution. In 2020, for example, Tunisia was deemed to be more equipped to adapt than Morocco, owing to its better functioning government, less corruption and a more equitable distribution of resources. Morocco in turn had a higher adaptive capacity than Algeria. Tunisia may as a result have a sounder business environment to deal with water stress for example and to build the necessary water conservation infrastructure. It may also have a more effective government with better planning, implementation and monitoring of water sharing and conservation scheme. However, North African countries often found themselves looking to the northern shores of the Mediterranean in search of financial and technical support. North African countries and cities continue to seek technical and financial assistance from EU programs aimed at Europe’s southern neighbourhood, such as ClimaMed, Clima South, MeetMED, Climate 4 Cities, CES MED, and SUDEP South. Morocco is by far the most successful actor across the MENA region in obtaining financial and technical support. According to the most recent estimates, it received 54% of all approved multilateral climate finance in the region, followed by Egypt, which received 27%.

The orientation of the region towards Europe is expected to increase in response to the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), a requirement by the EU’s Fit for 55 legislative package that imposes carbon tariffs on certain business sectors seeking to export into the EU. Egypt is currently one of the top 20 exporters whose goods are likely to be affected by the CBAM.

National climate action

Energy transition towards renewable energy is one of those mitigation actions that provide economic co-benefits for the region, yet the adoption of renewable energy remains below its potential. In the decade to 2020, renewable electricity generation grew by just over 40%, led by an expansion in solar photovoltaic, wind, and solar thermal systems.

The national performance in terms of commitments to mitigating climate change and energy transition varies widely between the five North African countries, with Morocco leading the way. It has committed to reducing its emissions by 45% (compared to a business-as-usual scenario) by 2030, a commitment that has been assessed as ‘almost sufficient’ to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. Morocco also is reasonably on track to meet its goal to source 52% of its electricity from renewable energy by the same year, with renewable energy accounting for 37% of its electricity in 2021. This goal is partly driven by the country’s need to improve its energy security and reduce its dependence on imported energy sources. Moreover, Morocco has made a number of export-oriented mitigation efforts including an ambitious renewable energy project that will provide electricity to the United Kingdom and a large scale, cost-effective Green Hydrogen production system.

Similarly, Egypt is also making some efforts to mitigate its carbon emissions, including investing in solar and wind power generation and exporting green hydrogen. Although it missed its target to source 20% of its electricity from renewable energy last year, it has set a more ambitious goal of sourcing 42% of its electricity from renewables by 2035. The country’s ambition to become a regional energy hub is driving its investments, which also include exporting natural gas.

Poor climate cooperation

The common climate and socio-economic challenges in North Africa lend themselves to climate collaboration between the regional countries. Sharing experiences and pooling resources could reduce the adaptation effort required at the national level. Yet the region has very limited economic integration. Political turmoil, the civil war in Libya, and longstanding tensions between Morocco and Algeria have also further impeded the prospect of any such collaboration. The only frameworks available for climate collaboration in the region extend beyond its geographic scope. These include forums established by the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM), the 5+5 Dialogue, and the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA).

Even the advent of climate negotiations in North Africa again during COP27 in Egypt has not managed to stimulate climate collaboration. Like its predecessor in Marrakech back in 2016, COP27 was not presented as an opportunity for North Africa but rather as a platform to give voice to the continent and the wider global south in climate negotiations.

The way forward

North Africa’s long-term prospects and stability will depend on how this area will deal with the challenges of climate change. The extent to which the regional impacts of climate change cascade and intersect with current vulnerabilities and risks makes it less like a future challenge that should give way to other pressing issues. Instead, climate change adds another layer of socio-economic complexities that influence the region today and will continue to do so in the coming years.

The earlier the region recognises this and prioritises mitigation and adaptation climate action, the more likely it could avoid climate change’s worst impacts. The sooner North African countries acknowledge that they cannot fight this battle alone, the sooner they will set their differences aside and collaborate for a better future for their people.

Jihadism in North Africa: A ‘Resilient’ Threat in Times of Global Crises

Lorenzo Fruganti, Junior Research Fellow at the Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI) MENA Centre. | @FrugantiLorenzo

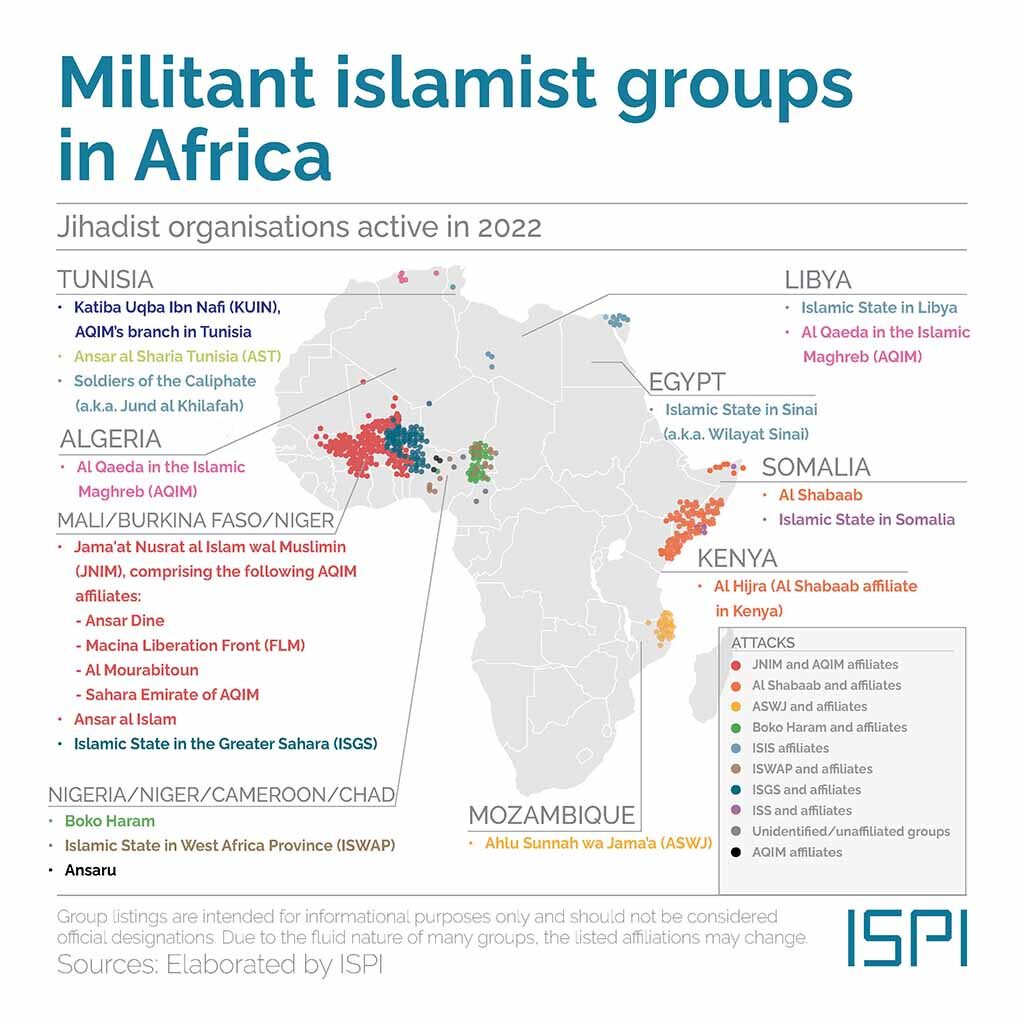

The COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have acted as catalysts for pre-existing geopolitical dynamics, shifting the focus away from the War on Terrorism paradigm that shaped much of the international community’s political and economic engagement with the Middle East and North Africa region (MENA) in the aftermath of 9/11 towards an era of multipolarity and great power competition. Over the last few years, consecutive counterterrorism operations, the enforcement of strict national anti-terrorism legislations, and the implementation of successful deradicalisation and rehabilitation programmes have largely abated the threat posed by jihadist groups in MENA countries, particularly in North Africa. Among other things, the findings of the Global Terrorism Index 2023 seem to confirm this trend. While the Sahel has progressively emerged as the new epicentre of jihadi terrorism over the last decade, with deaths in this area accounting for 43% of the global total in 2022 (a 7% increase compared to 2021),[1] fatalities from terrorism in the MENA have fallen by 42% in the last three years and by 32% in 2022. Although the impact of terrorism varies considerably within the MENA, North Africa – in particular – records a steady decline in extremist violence. The number of violent attacks associated with militant Islamist activity in this region is now down to pre-Islamic State (IS) levels. The 276 casualties linked to jihadist terrorism in North Africa in 2022 represent a 14-fold decrease from the 4,000 deaths that occurred in the area in 2015, when IS was at its height. Against this backdrop, Morocco stands as the safest country in North Africa (83rd position in the Global Terrorism Index rank), having not recorded a terrorist attack in the last five years. Conversely, Egypt is among the 20 states worldwide most affected by terrorism (16th position), which is no surprise given that nearly all the reported militant Islamist activity in North Africa over 2022 took place in the country (about 90%). In between Egypt and Morocco rank Libya, Algeria and Tunisia (32nd, 37th and 40th positions, respectively) with a medium-to-low impact of terrorism.

The main trajectories of jihadist violence in North Africa

In Egypt, a major security crackdown coupled with the government’s public investments and infrastructure policies in the Sinai Peninsula has, over the last few years, diminished the presence of the local branch of the Islamic State, also known as Wilayat Sinai or Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (ABM). However, according to the United Nations (UN), the group – which is composed of around a thousand fighters – has remained active and resilient throughout 2022, its main targets being native communities and Egyptian security forces. The latest violent clashes between the Egyptian army and ABM in 2022 occurred in areas near the Suez Canal, testifying to the effort that the organisation is making to expand its activities in Egypt beyond north-east Sinai towards new strategic regions. Since 2013, more than 3,000 people have been killed and more than 12,000 wounded in terrorist attacks in the Sinai Peninsula.

In Libya, jihadist groups have continued to face several challenges following successive strikes against their positions, especially in the southernmost region of Fezzan, where the Islamic State and Al-Qaeda (reportedly present there with a hundred and three hundred members, respectively) are still active, albeit dramatically downsized compared to the past decade. Playing on the political and economic predicament in southern Libya, IS has kept cooperating with tribal elements involved in smuggling and illicit trade; this cooperation is a vital component of the group’s financing and creates the conditions for new recruitment processes. On the other hand, the local branch of Al-Qaeda (which has its main terrorist structures in the cities of Awbari and Sabha), depends mostly on a strategy of intermarriage and merging with local tribes to maintain legitimacy in southern Libya. According to a recent report by Europol, the organisation has become a logistic hub for Al-Qaeda affiliates in Mali. The deployment of Syrian mercenaries – often with radicalised profiles – by Russia (through the Wagner Group) and Turkey in Libya might pose additional security risks to the country.

Despite having not recorded any Islamist-inspired attack since 2018, Morocco remains vigilant over the offline and online threat of violent extremism. In recent years, the state’s security services have regularly thwarted IS terrorist plots relying on explosives, firearms or knives while also dismantling jihadist cells that operate in cyberspace. Meanwhile, the country has implemented rather successful de-radicalisation and reintegration programmes, such as ‘Moussalaha’ (‘Reconciliation’), which since 2017 has benefited hundreds of jihadists, both those arrested in Morocco and foreign terrorist fighters (FTFs) returnees.[2]

Jihadist organisations linked to Al-Qaeda remain extremely constrained in Algeria owing to both tight security mechanisms and reconciliation policies that allow jihadists who surrender to security services and provide them with information to receive amnesty and economic assistance. It is noteworthy that only a limited number of former jihadists who participated in these programmes in Morocco and Algeria have relapsed into violence.

Although it has seen an overall decline in jihadist attacks and arrests over the last five years, Tunisia continues to face a number of challenges related to violent extremism. Foiled plots in the country demonstrate the still effective organisational and operational capability of jihadist groups such as Katibat Uqba Bin Nafi (KUIN) and Jund Al-Khilafa (JAK), which – however weakened – are active in the mountainous zones along the Tunisian-Algerian border. The risk of attacks perpetrated by so-called “lone wolves” scattered across the national territory is also marring the national security landscape. Furthermore, unlike Morocco and Algeria, in Tunisia there seems to be still room for implementing more effective disengagement and de-radicalisation programmes. As it stands, Tunisian FTFs returnees are jailed or remain under strong surveillance by security services, as some de-radicalisation policies, such as ‘Tawasul’ (‘Connection’) have not received support (and hence the funding needed to operate) from the general public, which opposes the return of FTFs from Syria, Iraq and Libya.[3] Overcrowded Tunisian prisons, ruled by strict repressive measures (including torture), may entail additional risks for national security, continuing to serve as hotbeds of new radicalisations pathways or even worse, a new generation of jihadist fighters.

Increasing pressures from the Sahelo-Saharan region

The Sahelo-Saharan space has traditionally been shaped by deep political, socioeconomic and security connections binding Maghreb states to Sahelian actors. Largely permeated by terrorist groups that have proved quick to capitalise on local issues (including ethnic tensions, climate-related challenges, and lack of public services) to attract recruits, the Sahelo-Saharan strip has not only become a hotbed of jihadist activities in recent years, but it is also poised to turn into an export hub of the terrorist threat towards peripheral areas. While the Sahel instability has already produced spill-over effects on West Africa and the coastal countries of the Gulf of Guinea, where the existence and expansion of violent extremist organisations affiliated especially with the Al-Qaeda-affiliated Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wa al-Muslimeen, JNIM) are widely demonstrated, a similar scenario could also affect North Africa, reversing the significant achievements in terms of prevention, counterterrorism and de-radicalisation made by some regional states over the last few years. The range of military and intelligence cooperation initiatives (not involving Western actors) that were undertaken between Sahelian and North African countries to deal with the mounting jihadist threat in the former signal the intertwined security concerns both regions face. However, leadership rivalries and differences in strategic interests have hampered such efforts, and collaborative partnerships to address this transnational challenge remain fragmented.

The strategic shifts (and uncertain implications for the Sahel-Maghreb area) in the Sahel’s Western counterterrorism architecture following the relocation of US and European forces, and the increased activity of Russian Wagner mercenaries in Sub-Saharan Africa, notably in Mali since late 2021, raise additional fears of a jihadist contagion spreading across North Africa. Besides, geopolitical rivalries between France and Russia could undermine efforts to tackle the terrorism crisis in the Sahel, with counterterrorism cooperation between neighbouring states now being hostage to divisions between those states seemingly supported by Russia (Mali and Burkina Faso above all) or France (Niger).

The potential spillover into Libya and Tunisia

Against this backdrop, the enduring security vacuum in Libya is undoubtedly one of the main sources of instability associated with the potential spillover effects of jihadism from the Sahel region. The state’s weakness, particularly in the Fezzan region, could enable both IS and Al-Qaeda to gain strength by taking advantage of transfers of fighters not only from the Levant and Eastern Africa (Eritrea above all) but also from the Sahel through the country’s porous southwestern border. The current conflict in Sudan risks fuelling further instability in Libya and across the entire Sahel. According to observers, especially worrying is the impact of the war in Sudan on the proliferation of weapons, which could potentially strengthen the various armed groups and militias already operating in a region plagued by continuous instability and coups d’état, with severe repercussions on jihadist violence in Libya as well.

The insecurity and jihadist violence plaguing the Sahel might also reverberate in Tunisia, due to the presence and activity of Tunisian terrorist fighters in the Sahelo-Saharan space and southern Libya. According to some experts, around 100 Tunisians are fighting in the Sahel today, in addition to almost 600 fighters who are still part of jihadist militias in Libya, especially in the Fezzan. Tunisians’ presence in the Sahel is also likely to strengthen Tunisian-Malian jihadist bonds, which have existed for over a decade. As long as Tunisia’s nationals fill the ranks of jihadist groups in Libya and south of the Saharan desert, these connections (manifesting themselves in new supply routes and funding sources) could be reactivated and lay the groundwork for new attacks in their country of origin and in other North African states. Although nothing seems to indicate that this is the case for the time being, the issue deserves close attention, given the persistent crises in Libya and the Sahel. Besides, Tunisia’s participation in multilateral training and capacity-building initiatives (such as NATO’s Operation Sea Guardian) and joint military exercises (such as African Lion 22 and Africa Lion 23)[4] with a focus on counterterrorism underscores the country’s rising concerns for the future stability of the Sahel region and the southern shore of the Mediterranean.

Algeria’s quest for a pivotal role in the Sahel-Maghreb

After the fall of the Qaddafi regime and the deterioration of the political and security situation in Libya, Algeria has emerged as one of the key guarantors of peace in the Sahel-Maghreb area, striving to bring stability to neighbouring Libya, Tunisia and Mali, and to securitise the Sahel region notably by means of joint military and security coordination. Overall, Algeria’s action has delivered mixed results. Many questions persist today about whether the country can play a pivotal role in the Maghreb-Sahel area. The volatile security situation and the ever-changing geopolitical context characterising the Sahel region may compromise Algeria’s endeavours. In addition to this, another important aspect should be considered. Challenging Algeria’s historical influence in the Sahel, Morocco has, over the last decade, consolidated its presence there by adopting a soft power alternative strategy to the predominantly ‘hard’ counterterrorism approach promoted by Algeria. The competition between these two countries contributes to averting the restructuring of a regional security framework to grapple with terrorism-related threats in the Sahel-Maghreb region.

Throughout the past fifteen years, regional instability and the presence of terrorist groups on Algeria’s borders have threatened the country’s security. For Algeria, which shares a 1,300 Km border and a common heritage of social and ethnic relations with Mali, the securitisation and stabilisation of the Sahel-Maghreb area have long been a matter of national interest.[5] The state authorities have opted for a mix of diplomatic and military strategies to tackle terrorism and criminal networks.[6] This process started with the signature of the 2009 “Tamnrasset plan” agreed to by the so-called pays du champ (Algeria, Niger, Mali and Mauritania), which led to the creation, in 2010, of a joint military operations centre known as Comité opérationnel conjoint des chefs d’état-major (CEMOC) based in Tamanrasset, and a joint intelligence unit – Unité de Fusion et de Liaison (UFL) located in Algiers. Such an initiative marked the first attempt to build a regional security architecture with an operational dimension in the Sahel. The pays du champ doctrine, as conceived by the Algerian authorities, consists of developing the capacities of the countries concerned to manage the security challenges in the region without relying on external actors; as a result, any cooperation initiative provided by the US or the EU should be limited to specific activities, basically training, logistical support and intelligence. If, on one side, cooperation between CEMOC member countries in analysing security threats and sharing border management responsibilities set a praiseworthy model, the initiative has not yielded tangible results thus far, the main obstacles being the lack of mutual trust among participants and the inability to pool military forces.

The discontent with both the CEMOC and the UFL and the hesitation of Algeria (rooted in its traditional doctrine of non-intervention) to respond to Mali’s request for direct military involvement in 2012 led five of its Sahelian neighbours (Mauritania, Niger, Mali, Chad and Burkina Faso) to establish in 2014 an alternative regional platform to combat terrorism in border areas of the region. The so-called G5 Sahel, which included CEMOC member states (Mauritania, Niger, Mali) while never comprising Algeria, was strongly supported by France, which has been happy to fill the leadership void that the North African country created in the Sahel-Saharan strip by refusing to support Bamako militarily. Today, however, the G5 Sahel seems to be reeling, especially after Mali’s military junta pulled out in May 2022. Aside from its military weaknesses, the G5 Sahel has been based on significant geostrategic shortcomings; by conceiving the Maghreb, the Sahel and West Africa as separate (static) sub-regional blocs and ignoring their deep geographic, political and security interconnections, the horizontal (east-west) logic of the organisation overlooks the north-south and interregional dynamics, even though the spread of crises and instability follows a ‘vertical pathway’.

While the G5 Sahel has shown its limits, Algeria has recently attempted to carve out a new space in the regional security dynamics. The visits to Mali of former Algerian Foreign Minister Lamamra (in September 2022) and new Foreign Minister Attaf (in April 2023) seem to show the country’s willingness to engage more prominently at the regional level by dealing with the increased terrorist threats and the spread of organised crime in the common neighbourhood area.[7]Algerian President Tebboune had already sought to speed up this progress of re-engagement through a 2020 constitutional amendment authorising Algeria’s army to deploy outside the country’s borders, provided certain conditions were met. If Algeria’s military involvement in case of an existential attack against a Sahelian neighbour remains a remote possibility, that now cannot be discarded. Moreover, as part of its efforts to diversify partnerships in the Sahel-Maghreb region, Algeria has invested significantly in the Trans-Saharan Highway Project. In doing so, the country aims to exert further leverage on and strengthen the mutual dependency with Sahelian governments, thus seeking to enhance its role as a key player in the area also in the fight against terrorism.

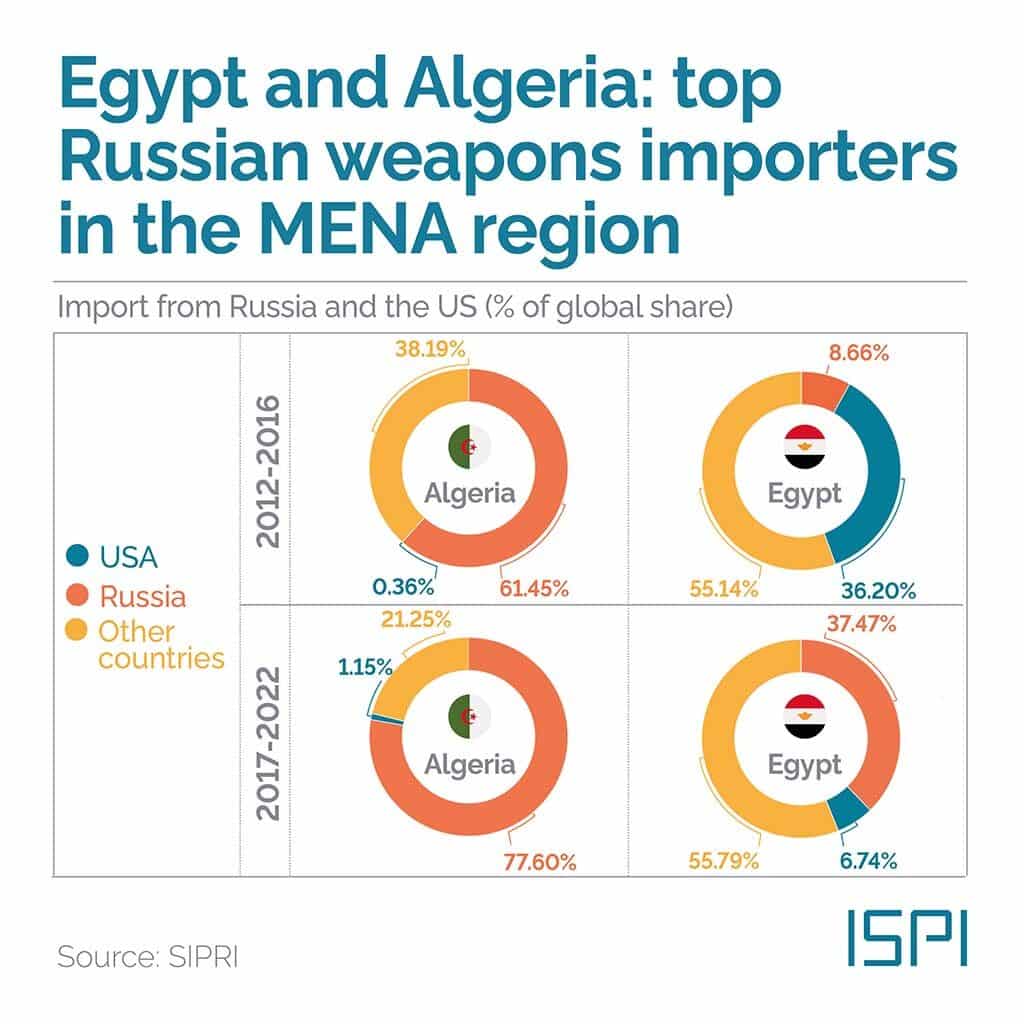

Despite the efforts to assume a leadership role in the Sahel-Maghreb, it remains to be seen whether Algeria will be able to play a stabilising role in this crucial area amid the collapsing Algiers Peace Agreement, the withdrawal of international troops and the rise of Russia’s influence in the Sahel. Undoubtedly, Algeria’s expertise and knowledge of militant groups across the Sahel may be an asset to the success of any future multilateral security mechanism taking shape in the region. However, the presence of the Wagner Group in Algeria’s border areas – as part of Russia’s African projection – could pose extra challenges. The Maghreb country, which is Africa’s second-largest importer of Russian arms, has further strengthened its economic and military relations with Moscow over the past few years and has reportedly allowed Russian military planes affiliated with the Wagner Group in Mali to use its airspace to carry out counterterrorism operations in the Sahelian country. Of course, this is not to say that Algeria has established official ties with the Russian Wagner group in Mali; on the contrary, in December 2022, Algerian President Tebboune regretted the deployment of Russian mercenaries to his country’s neighbour, calling on Mali’s military government to drop the costly services of the Russian private contractors and allocate its financial resources to the state’s economic development instead. This stance by President Tebboune has probably long been awaited by the French government, which pointed to the controversial deal between the Malian junta and the Russian Wagner Group as a crucial factor in pushing Paris to withdraw its troops from Mali throughout 2022.

All in all, Algeria is seemingly trying to perform a delicate balancing act between Russia, Mali and France, with the aim to preserve the strong relations with Moscow, favour a political solution in the Malian conflict by supporting the junta in Bamako, and keep the fluctuating relations with Paris on track (some observers believe that the French withdrawal from Mali might boost Franco-Algerian cooperation, especially on the Sahel crisis’ file). While it is premature to predict how this uneasy balance will evolve, some Western officials and experts have talked about the “destabilising role the Wagner Group plays in the Sahel” and argued that the presence and activity of Russian mercenaries might directly affect the jihadist threat stemming from the region. In this respect, it has been stressed that the deployment of the Wagner Group to Mali since late 2021 has energised local jihadi organisations, providing them with new recruitment opportunities and a more propitious operating environment in the country. This seems further evidenced by the fact that there was an increase in JNIM attacks across Mali in the 2022 rainy season compared to the previous year’s rainy season, and terrorist acts by IS within Mali also surged across these timespans.[8] Although the relocation of anti-jihadist French and European military forces from Mali might also have contributed to this trend, there should be a concern that Wagner’s deployment to Mali or any other Sahelian countries (such as Burkina Faso, Chad and Niger) could make the security context in that area and the neighbouring states even worse, with a likely increase in the terrorist risk level for North Africa as well.

The Algerian-Moroccan rivalry in the Sahel region: another obstacle in the fight against jihadism

In 2014 Algeria was wary that the France-supported G5 Sahel was created with the primary objective of reining in Algerian regional influence. Back then, the country was indeed suspicious of its neighbours, especially the so-called pro-French axis led by Morocco.[9] Unsurprisingly, even before the G5 came into existence, the CEMOC and the UFL were built to contain not only Western interference in Algeria’s close backyard but also regional competitors, first and foremost Morocco.

Despite its peripheral position vis-à-vis the epicentre of insecurity in the Sahel, Morocco has for years enhanced its diplomatic engagement in Africa, as testified by the country’s reintegration into the African Union in January 2017 after 33 years, as well as by Rabat’s application to join the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in February 2017. In order to confront jihadism and halt its northward advance, Morocco has reinforced its security partnerships with Sahelian countries. Building on the common Islamic heritage with the latter, the state has developed a soft power strategy based on the export of a cultural and religious model. Rabat has offered religious formation to the ulema of Mali and Niger as part of this strategy, instructing them in the ‘moderate’ Islam practised in the kingdom. According to Moroccan officials, the government has thereby addressed the need to tackle jihadist radicalisation in the Sahel while at the same time proposing an alternative to the “hard” counterterrorism policies promoted by Algeria.

On the one hand, Morocco is widely considered to be one of the leading African countries in the fight against terrorism; its involvement and efforts within multilateral bodies devoted to counterterrorism and countering violent extremism are particularly valued: among others, today the country serves as co-chair of the Africa Focus Group in the US-led Global Coalition to Defeat Daesh/ISIS; it has been hosting the Africa Lion military training for 19 years (the 19th edition, which took place in seven regions across Morocco, confirms the deep military cooperation between the Maghreb country and the US), and has just handed over the presidency of the Global Counter Terrorism Forum (GCTF). Additionally, since June 2021 the kingdom’s capital has hosted the headquarters of the United Nations Office of Counter Terrorism and Training in Africa (UNOCT) – the first of its kind on the African continent.

On the other hand, Morocco’s desire for expansion in the Sahel has projected the kingdom’s historical rivalry with Algeria into the region, which is mainly linked to the conflict over Western Sahara. Consolidating a network of regional alliances is functional for Rabat to gain political and diplomatic support on the Sahrawi question. The latent conflict between Algeria and Morocco in Western Sahara and their divergent interests in the Sahel have, until now, further complicated the development of joint security cooperation processes in the counterterrorism field.

In Tunisia, Civil Society Is Back in the Trenches

Emna Ben Arab, Assistant Professor, University of Sfax | @EmnaBenArab

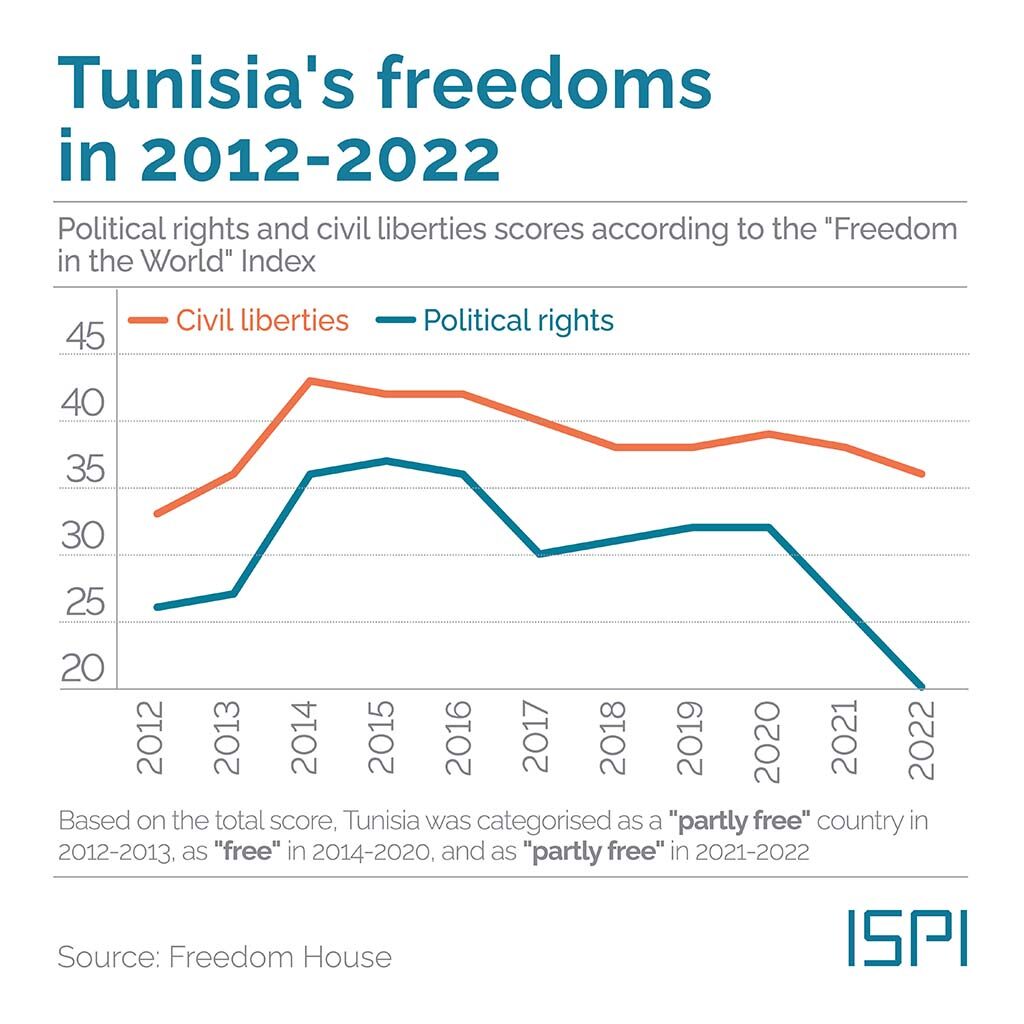

Twelve years into the Tunisian uprising, the country is standing at a crossroads yet again. In 2019, Tunisians democratically elected Kais Saied, an anti-establishment populist who, from the start, declared his hostility to the system in place. He institutionalized his ideas through a new Constitution (adopted after a referendum held on July 25, 2022) that established a hyper presidential system and undermined checks and balances. These measures, he claims, prioritize a meaningful transformation of government and society over a superficial process of democratization.

Kais Saied’s actions have impacted all of Tunisia’s body politic; and civil society is, now more than ever, at the heart of this transformation. Before the 2011 uprising, civil society was limited to a body of associations closely tied to the regime and operating on its behalf. Their activities were circumscribed, and their area of intervention was often confined to providing services including food, education, and health services on special occasions. Associations opposed to the regime, whose number did not exceed 10, had a confrontational relationship with the authorities and did not have much room to operate.

The evolution in civic action

Over the last decade, two turning points significantly impacted the status and work of civil society organisations. After the 2011 uprising, civil society was given a meaningful role and the space needed to operate freely as part of the democratic transition. The Decree-Law on Associations (No. 2011-88 dated September 24, 2011), enacted with a liberal outlook in line with international standards, took a corrective course of action relative to the previous law, and aimed at regulating associative life and offering an enabling environment for associative action. It stipulates that civil society organisations can be freely established and carry out a broad range of activities, lobby the authorities regarding laws and policies, and receive foreign funding without government authorization. Thousands of associations were, therefore, established taking advantage of the new-found freedom away from state control and other restrictions that might be imposed on them.[10]

Keeping up with the political evolution in Tunisia toward strengthening the rule of law, protecting liberty, and establishing participatory democracy, civil society assumed new roles that transcended its previous role and became active in previously unexplored areas such as government accountability, human rights monitoring, and reinforcing the country’s transitional process and democratic practices. The post-uprising period witnessed a change of mindset in both government and civil society that took them away toward a cooperative approach. This has allowed civil society to gain momentum and vivacity that would grow over the years.

Associations such as ‘Mourakiboun’ (‘Observers’), the Tunisian Association for the Integrity and Democracy of Elections (ATIDE) or I Watch, have ensured, with other independent bodies, that elections take place in a free and fair manner. The ‘Al-Bawsala’ (‘Barometer’) association has monitored the work of parliament and issued regular reports thereof, watched the proper execution of the State budget and ensured citizen oversight of municipal activities. Other associations became active in areas previously inaccessible to civil society such as police reform (Islah), financial transparency (ATTF), observation of the judiciary (OTIM.)

Civil society also offered an important framework for dialogue. The National Dialogue that was launched under the auspices of four national organisations – which are the Tunisian General Trade Union (UGTT), the Tunisian Union for Industry, Commerce and Handicrafts (UTICA), the National Bar Association (ONAT), and the Tunisian Human Rights League (LTDH) – spared the country a civil war after the political assassinations of 2013. The National Dialogue Quartet provided a platform for dialogue among all political stakeholders and came up with an initiative based on the principle of the peaceful alternation of power, and with a roadmap to which all were committed. This unblocked a rapidly deteriorating political situation and earned the Quartet the Nobel Peace Prize in 2015.

Instrumental in raising public awareness, civil society groups expressed reservations about certain provisions included in the proposed draft constitution of June 1, 2013, regarding rights and freedoms and the new status of women as complementary rather than equal to men. A number of women’s associations, along with the media, undertook to monitor decisions that might threaten women’s rights, and to follow up the process of drafting the new constitution. This ended up with articles 21 and 46 of the 2014 Constitution protecting women’s rights and stipulating that women stand in an equality relationship with men.

Civil society also played a significant role in safeguarding public security, for instance, by putting pressure on the government to address the broader issue of Tunisian returnee from foreign combat theaters. In 2017 and in response to the Tunisian government’s intention to pardon and reintegrate foreign fighter returnees who had not fought with jihadist groups, Tunisian citizen groups launched demonstration. The powerful worker’s union, the General Union of Tunisian workers (UGTT), also declared its rejection of a proposed repentance law for terrorists who, it argued, had to be prosecuted before Tunisian courts.

Civil society, thus, assumed during the last decade a new set of roles that involved monitoring, lobbying, raising awareness and providing a framework for dialogue. It moved away from being a counter-power and a force of protest that exerted pressure on the authorities to becoming actively involved in national issues of public concern, and assuming a new participatory role that involves taking initiatives and making suggestions.

Still standing under pressure

Following the July 25, 2021 power grab, civil society has been instrumental in standing up to President Saied, in part by organising protests and sit-ins in response to his decrees. Civil society groups also mobilized after his address to the National Security Council on February 21, 2023 in which he warned against a long-running plot to change Tunisia’s demographic composition and alter its Arab and Muslim identity through migration from sub-Saharan Africa. Tunisian civil society organisations announced the creation of an “anti-fascist front” to oppose the president’s racist undertones and migrant crackdown. The members include the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights (FTDES), the Tunisian League for Human Rights (LTDH), the National Union of Tunisian Journalists (SNJT), and the Tunisian Association of Women Democrats (ATFD).

July 25 was the second turning point for civil society in Tunisia. Restriction and vilification of civil society came along with democratic backsliding. In a videotaped speech on February 24, 2022 President Saied accused civil society organisations of serving foreign interests and announced his intention to ban all funding from abroad for them in the name of national sovereignty. Indeed, a draft law amending Decree 88 targeting civil society organisations was leaked in earlier February 2022. Echoing the security-focused language used in other authoritarian civil society laws like Egypt’s, the new draft law would allow authorities to reject the applications of civil society organisations that are deemed to pose “threats to national unity or threats to the democratic and republican nature of the state” (Article 4, Article 10). It would require civil society organisations to receive government authorisation to operate and subject their foreign funding to prior approval from the Central Bank, giving authorities sweeping powers to interfere with the way civil society organisations are formed, their functions and operations, and their funding.

This, if it goes into effect, will deal a blow to the whole civil society fabric as most associations resort to foreign donors. According to a survey of 100 civil society organisations in Tunisia published in 2018, nearly two-fifths said that they relied either partly or mainly on funding from abroad. Preventing CSOs from accessing foreign funds will, therefore, significantly impact their work as they are often denied funds from a domestic government source when they apply for them. Besides, unlike political parties, individuals of the private sector have little if no interest in funding CSOs. Public surveys reflect a lack of trust in civic actors in Tunisia.

The erosion in public trust

As the country becomes further polarised, civil society reflects the division of the country along political and ideological lines. Among the challenges that exacerbate mistrust is the secret ties held by many civil society organisations with major political parties. The dominating political forces, the seemingly irreconcilable blocs of the Islamists and the seculars, have their share of CSOs that were used before, during and in the aftermath of elections. Although the law prevents the creation of associations from serving as a cover for funding political parties or their candidates in an illegal way,[11] parties and individuals, in the absence of effective methods to control political funds, often made use of associations for this purpose. This allowed them to escape the control of the banking system and the monitoring of party financing, providing them with a great deal of political leverage over minor parties in the elections (e.g., Ennahdha and its “shell” associations, Qalb Tounes and Yerham Khalil association, Olfa Terras[12] and Fondation Rambourg-Ich Tounsi, etc.).

Another issue that impacts the perception and credibility of Tunisian NGO’s are the activities of some associations. As post-2011 Tunisia opened to freedom and democracy, an unprecedented number of associations – up to 17,000 – were created. Taking advantage of the weakened State, 48% of these associations did not abide by their declared scope and objectives and 19% operated under the cover of religious and charity organisations, serving as facilitators for arms and fighters smuggling, and providing logistics for fanatical jihadist preachers to address and brainwash disillusioned young people.[13] These “shell” associations were often financed by foreign donors or by unknown sources who set the agenda of their activities in return for funding.

Although one of the significant challenges facing the transition in Tunisia has been to gain greater control over foreign funding and make good use of it in a transparent manner, this should not be an alibi for the authorities to reverse the post-2011 hard-won gains of civil society. In view of the role that civil society plays in the management of public affairs, and in line with the principle of participatory democracy enshrined in the country’s 2014 Constitution, civil society should be further empowered, rather than undermined, to help Tunisia navigate this challenging period. Associational freedom is an essential component of the democratic transition, a political process whose success relies on society’s buy-in. Providing an environment that promotes associative action depends not only on the laws and regulations in force, important though they are, but also on the complementarity between all the parties involved.

Civil society actors will have to take a position as to how the country can achieve a smoother democratic transition while it is still possible. They will also have to address how the country can go about protecting individual and collective rights and freedoms. So far, their hesitancy regarding the political and economic risks looming over the country and the endangered liberties is likely to create a gap between them and the general public they are meant to mobilise. This gap will undermine CSOs’ ability to act and raise awareness. It can also damage their credibility as an opposition movement that should be capable of preserving and strengthening the post-2011 gains.

In North Africa, Startups and NGOs Drive Local Innovation. What Is Missing?

Intissar Fakir, Senior Fellow and Director, North Africa and Sahel Program, Middle East Institute | @IntissarFakir

Innovation is often cited as the prerequisite for development, growth, and prosperity. New ways to improve on existing practices and approaches, curiosity, and the ability to carry that forward into new ideas, discoveries and inventions help economies thrive, populations develop, and lives prosper. In the North African context, innovation is charting an uneven course. This human ability to improve, build, and innovate is at times fed by state institutions or hindered by them.

The state of innovation in North Africa

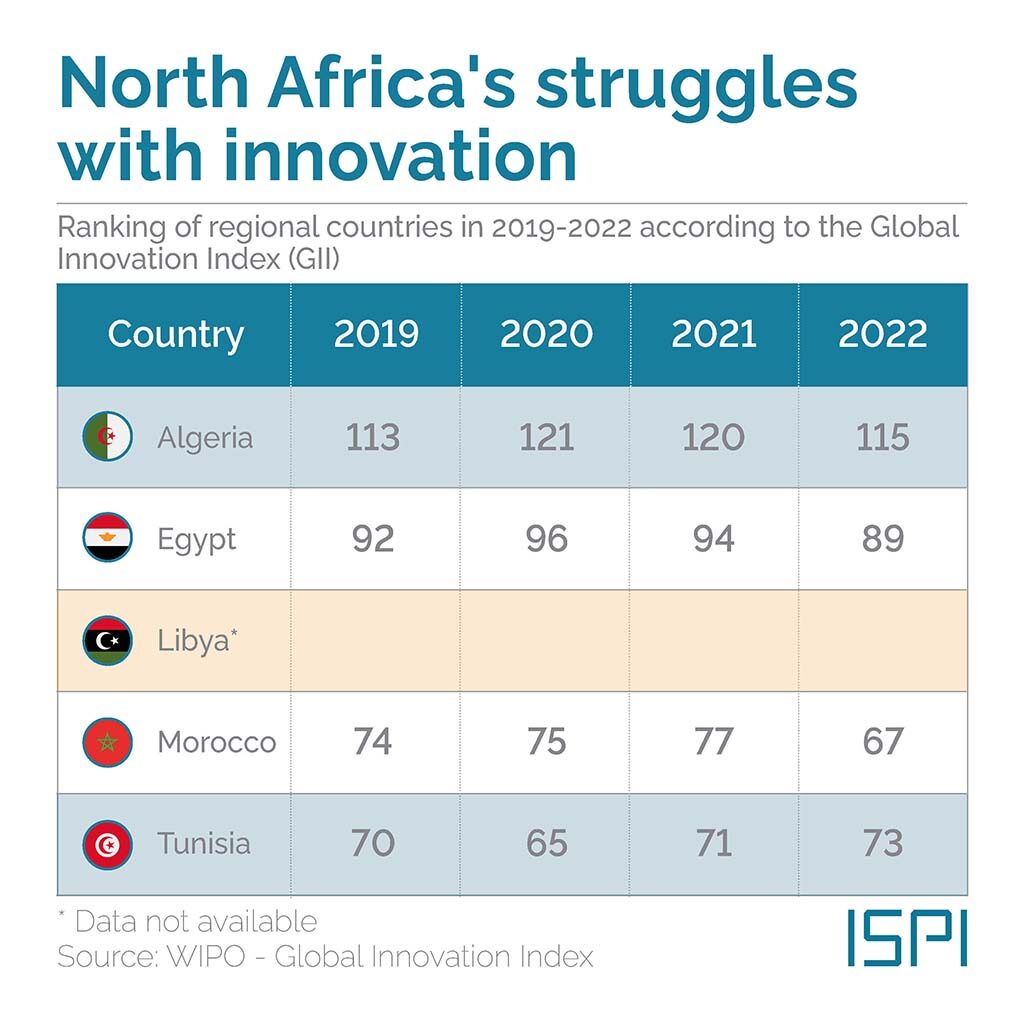

Of the publications that measure advances in the state of innovation, the World Intellectual Property Organization’s Global Innovation Index highlights the unevenness of regional economies in this regard. In the broader context, the North African countries of Morocco and Tunisia are in the middle showcasing signs of recent progress. The index relies on two sub-indices. The innovation input sub-index measures five indicators: the state of regulatory and political institutions, human capital and the extent of Research and Development (R&D), a market assessment, and an evaluation of the state of the business sector that looks at the existence of innovation linkages, the knowledge of works etc. The second is the innovation output sub-index which looks at outputs in knowledge creation, accumulation, and distribution, and creative outputs such as good services and assets.

| Country | Global ranking |

|---|---|

| Israel | 16th |

| UAE | 31st |

| Turkey | 37th |

| KSA | 51st |

| Qatar | 52nd |

| Iran | 53rd |

| Kuwait | 56th |

| Morocco | 67th |

| Bahrain | 72nd |

| Tunisia | 73rd |

| Jordan | 78th |

| Oman | 79th |

| Egypt | 89th |

| Algeria | 115th |

The World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Competitiveness Report also provides a scale of innovation ecosystems as one of the 12 measures of competitiveness. In the 2019 edition, of the 12 pillars, which include infrastructure, ICT adoption, skills, market system, market size, macro-economic stability, business dynamics, labour markets, and financial systems, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region’s lowest score was on the innovation ecosystem index. Yet, this was also the pillar where the region showed the most improvement second to ICT adoption, underscoring the distance traversed and the improvements gained with effective policies and investments. The following chart shows how countries in the MENA rank on the WEF Global Competitiveness Report’s Innovation Capacity Index, which looks at interaction and diversity, R&D (measuring, among others, patent application and R&D spending as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product, GDP), and commercialization.

| Country | Global ranking on innovation capacity |

|---|---|

| Israel | 15th |

| UAE | 33rd |

| Saudi Arabia | 36th |

| Qatar | 38th |

| Turkey | 49th |

| Oman | 57th |

| Egypt | 61st |

| Jordan | 65th |

| Bahrain | 64th |

| Iran | 71st |

| Morocco | 81st |

| Algeria | 86th |

| Tunisia | 92nd |

| Yemen | 130th |

Other attempts to quantify the state of innovation include the Bloomberg Innovator Index, which provides a ranking of the top 50 innovators and measures similar indicators and how they perform combined. These focus on R&D spending, the state of manufacturing, the presence and performance of high-tech companies, the prevalence of post-secondary education, the percentage of research personnel, and finally, the number of patents filed. The patent measure is particularly challenging because, in environments like Tunisia, patent development is inherently different as it faces issues such as the examination of the patentability of innovation, the high cost of protection and the lack of expertise in patent drafting. Hence, there is still much work educational institutions can do by providing training and support, technology watch and access to patents, reading patent claims and mapping to lower that hurdle for young innovators and students.[14] In the 2015 edition, Tunisia and Morocco made the cut, with Tunisia ranking 44th and Morocco in the last position at 50th. By global comparisons, these figures suggest the limited ability to innovate within North African economies due to the usual inhibitors. Still, they also highlight some notable improvements made over recent years.

The government drive to support innovation