Text originally published on 11/11/2021 in El Mundo.

These are not good times for the Maghreb, or for its neighbourhood to the north of the Mediterranean or to the south in the Sahel. The two main powers in north-west Africa, Algeria and Morocco, find themselves locked in a spiral of accusations, threats and hostile gestures that show no sign of relenting in the near future. They have a great deal in common in human and cultural terms, but their political regimes differ sharply (a conservative monarchy versus a populist republic). Where they resemble each other, however, is in their use of authoritarian methods to govern and in the power that their respective security services accumulate. They also share the fact that many of their citizens would, if they could, leave their country to seek a better life elsewhere.

Algiers and Rabat have had strained relations since they both gained independence in the mid-20th century, due partly to the consequences of colonialism, partly to local competition for regional hegemony and partly to concepts of sovereignty inherent to authoritarian systems. There have been periods of acute tension between the two countries, leading occasionally to brief armed conflict in the 1960s and 70s. But not everything has been fraught. There has also been cooperation at various levels and attempts to make headway on regional construction, such as the creation of the Arab Maghreb Union (with Libya, Mauritania and Tunisia) in 1989, although the organisation’s useful life was very brief.

The construction of the Maghreb-Europe Gas Pipeline (MEG), which was opened in 1996 and transported natural gas from Algeria to the Iberian Peninsula via Morocco, was an attempt to provide a backbone to the western Mediterranean by means of major strategic infrastructure and to generate trust and a shared interest between Algeria and Morocco. Mutatis mutandis, if this was the Maghreb’s equivalent of the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community (given the importance of that organisation to the formation of the EU), the shutting down of the MEG just when it had reached its 25th anniversary certifies the demise of this attempt. Today, the pipeline between the two countries is closed, their borders are sealed, their airspace has shut down and diplomatic relations have been severed.

“The degree of conflict between Morocco and Algeria is now heightened, with the potential to rise further and at levels that have not been seen for almost four decades.”

The degree of conflict between Morocco and Algeria is now heightened, with the potential to rise further and at levels that have not been seen for almost four decades. The triggers are manifold and are related to the internal situations of both countries (hit by the social and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic), regional geopolitics (with fiercer competition and tougher positions) and the influence of external actors, with the backdrop of the Western Sahara conflict.

In their own ways, the Moroccan and Algerian regimes are each displaying an increasingly militant nationalism, chiefly directed at each other. Both are facing adverse socioeconomic situations domestically, aggravated by the effects of the pandemic, with significant falls in GDP and job losses. There is also a domestic questioning of the political systems and the respective states’ ability to discharge their functions effectively (to provide public services, create economic opportunities and combat corruption). This set of factors tends to be associated with a search for distractions, which are often found on the other side of the border. In the absence of strong economic recovery, a continuation of this trend seems likely.

Turning to the triggers of the current crisis in terms of regional geopolitics, the animosity that has long been brewing between the regimes in Algiers and Rabat has continued to build up and is manifesting itself in increasingly aggressive statements and more hostile gestures. Algiers is seeking to reactivate its foreign policy after a period of lethargy amidst the inaction of the previous head of state, and wants to stake out its territory vis-à-vis a Moroccan foreign policy that has become more assertive.

A cause and also a consequence of these tensions is the arms race engaged in by both countries, which jointly import more arms than the rest of the African continent combined. This means that a considerable chunk of GDP in both Morocco (4.3%) and Algeria (6.7%) is spent on arms purchases and defence, with one eye on the neighbouring country. These resources are not channelled towards other necessary and urgent projects involving social spending, infrastructure, sustainability and modernisation.

The single event that possibly did most to raise the temperature of conflict in the Maghreb in recent decades was the succession of three tweets the then US President Donald Trump published on 10 December 2020, having failed to win re-election the preceding month. The US unilaterally recognised Morocco’s sovereignty over Western Sahara –a territory that the UN regards as ‘non-self-governing’– in exchange for Rabat announcing that it would establish full diplomatic relations with the State of Israel.

This hasty Trumpian transaction had two main outcomes: (1) it led Rabat to believe that the announcement settled the conflict in its favour, which translated first into a more vehement foreign policy, unleashing crises with Germany and Spain, and subsequently into frustration when it became apparent that no other major country or international organisation (the UN, the EU, the AU or the Arab League) followed Trump’s lead; and (2) it destroyed the unstable equilibrium between the two competitors for regional hegemony in the Maghreb –Algeria and Morocco–, culminating in the severing of diplomatic relations between the two in August 2021, in the midst of an escalating barrage of mutual accusations, displays of animosity and retaliatory threats.

“[…] Spain faces a more complex neighbourhood to its immediate south, with new problems in addition to those that pre-date the pandemic and had not been resolved […]”

All the above mean that Spain faces a more complex neighbourhood to its immediate south, with new problems in addition to those that pre-date the pandemic and had not been resolved (of an economic and social order, in bilateral relations and with the EU). Authoritarianism, which lies at the root of many of these problems, may feel that it has strengthened itself internally by taking a harder line in its gestures abroad. However, this seems unlikely to contribute to the building up of a region of peace, stability and shared prosperity.

Although it does not seem the most probable outcome, the possibility of an increase in tension between Algeria and Morocco unleashing either direct armed confrontation or with the participation of the Polisario Front cannot be ruled out. A year ago, the latter, which calls for the self-determination of Western Sahara, declared the end of the ceasefire with Morocco, maintained for 29 years, arguing that the peace process brokered by the UN was serving only to underpin the status quo favourable to Morocco. In the current context, nothing seems to indicate that this process is going to be successfully revived, even after the appointment of the UN Secretary General’s new personal envoy for Western Sahara.

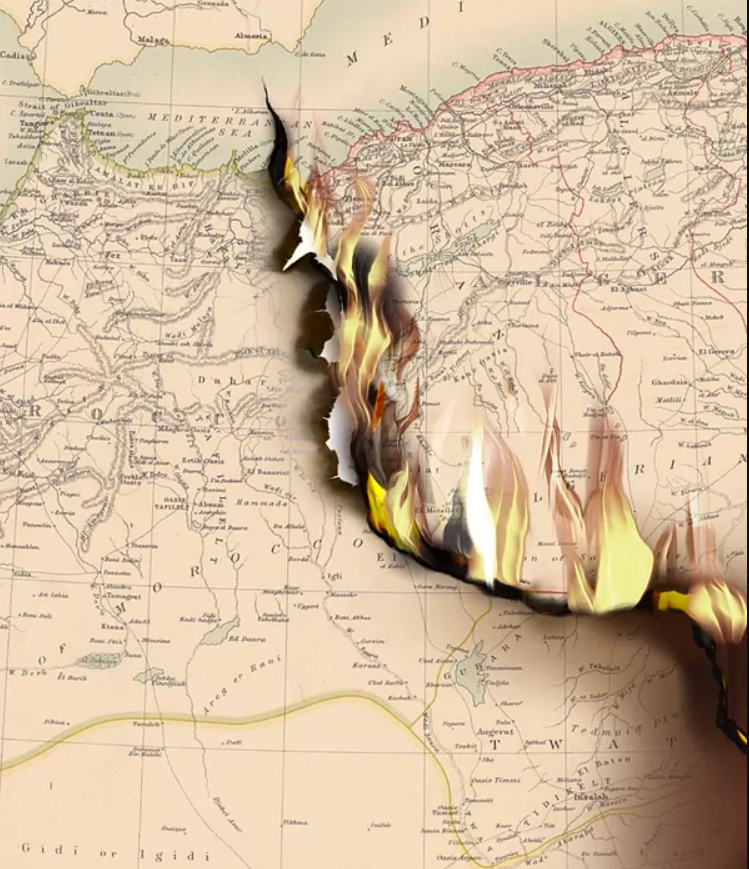

The growing tension of recent months is a reminder of the fact that what happens in the Maghreb has repercussions well beyond the region itself. Nowadays, it is not an area that conveys stability or is making progress towards greater regional integration (in addition to the spat between Morocco and Algeria, there are the self-coup by the erratic President of Tunisia in July and doubts about the political process to heal the profound fractures in Libya). As things currently stand, an accidental or deliberate spark could ignite North Africa, destabilising its neighbours in the Mediterranean and the Sahel.

There are too many tensions in the Maghreb and an urgent need for de-escalation channels to prevent matters from getting out of hand. Now more than at any time in decades, determined efforts and coordination between influential capitals in Europe and North America are required. The question is whether the actors who can contribute to changing the current trend are devoting the necessary attention to the Maghreb, in the midst of so many challenges piling up on the international agenda.