Theme

With China’s rise to the status of global power, its relationship with the Maghreb has witnessed substantial growth, generating both risks and opportunities for countries in the region.

Summary

The People’s Republic of China’s engagement with the Maghreb dates to the 1950s, but the Asian giant has significantly increased its economic, political and –to a lesser extent– cultural engagement with the region since the beginning of the century. Despite much fanfare about the advantages of South-South cooperation, China’s economic relations with the Maghreb reproduce characteristics of unequal trade. Whereas Chinese construction companies have stifled large infrastructure contracts in the region, Chinese investments in the Maghreb have remained scant. The Belt and Road Initiative, launched in 2013, is set to consolidate further China’s presence in the region, something that the EU and the US perceive as a threat to their interests. Ultimately, for Maghreb countries, China provides an opportunity to move forwards in expanding and modernising their domestic infrastructure, while reducing their reliance on the West.

Analysis

(1) From anti-imperialist politics to business

The engagement of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) with the Maghreb[1] goes back to the 1950s, when the newly in-power communist party established ties with national liberation movements in the region. The Bandung conference in 1955 was a milestone for Sino-Maghreb relations. The conference was attended by Zhou Enlai, the Chinese Premier at the time, as well as delegations from Algeria’s National Liberation Front (FLN), Tunisia’s Neo Destour party and Morocco’s Istiqlal party, among others. Zhou Enlai’s speech at Bandung stated that China would side with the Third World to fight colonial domination and imperialism.

In this vein, Beijing played a key role in helping Algeria’s struggle for independence. Between 1958 and 1962, it provided assistance to the Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN) –the armed wing of the FLN– in the form of funds, arms and training for Algerian fighters. China was also the first non-Arab state to recognise the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic in December 1958. While in the 1980s revolutionary politics started to gradually lose their prominence in China’s foreign relations in favour of more pragmatic economic ties, China’s support of Algeria’s independence still underpins the currently strong bilateral relations. Today, Algeria is the only Maghreb country with a comprehensive strategic partnership (CSP) with China, the highest level of Chinese diplomatic partnership. The CSP signals the strength of the relationship and the willingness of Beijing to maintain a significant multi-level engagement with the country.

With China’s accession to the WTO in 2001, the creation of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in 2000 and the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum (CASCF) in 2004, relations between China and the Maghreb grew further. Although FOCAC and CASCF have generated much attention, the relations between China and the Maghreb have remained largely bilateral, limiting the bargaining power of the Maghreb countries as a region and allowing Beijing to generate more significant economic and diplomatic dividends.

That said, since the turn of the century, as the West perceived the Maghreb predominantly through a narrow security prism –at best as an ally in the ‘war on terror’ and at worst as a boiling reservoir of upcoming migrants–, China significantly increased its economic and political engagement with the region. Beijing’s deal is somewhat different; it emphasises large infrastructure projects and trade as key mechanisms to improve security. At the 8th Ministerial Meeting of the China-Arab Forum in July 2018, President Xi Jinping preached the virtues of his foreign policy flagship, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), insisting that development was key to resolving many security problems in the region. Xi announced at the meeting new loans worth US$20 billion and US$106 million in financial aid to the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), aimed to boost infrastructure construction, industrial revival and new trade relations.

With the BRI, China has shown renewed interest in the Maghreb.

This is due to a confluence of factors, including the Maghreb’s strategic location as a point of connection for maritime logistics between Africa, Asia and Europe; the middle-income status of Maghreb countries, which make them interesting markets for some Chinese products; and the free trade agreements between certain Maghreb countries and the EU, which provide an incentive for Chinese manufacturers to relocate their activities in the region to take advantage of these trade agreements.

In contrast, governments across the Maghreb largely perceive the BRI as an opportunity to help them close existing infrastructure gaps, attract investment and boost trade. All of them have signed memorandums of understanding (MoU) to join the BRI. Beijing’s non-interference policy, a cornerstone of its foreign policy, has made it appealing for developing countries, including those in the Maghreb, to engage with China. This principle officially compels Beijing to abstain from intervening in the internal affairs of other countries.

However, the endurance of China’s non-interference policy has been put to the greatest test in the Maghreb. Beijing expressed concerns over the 2011 NATO operation in Libya but decided not to use its veto power at the UN Security Council to halt the military intervention. Instead, it voted against Resolution 1973, which established a no-fly zone and provided protection for civilians. At the same time, it backed the Security Council’s decision to impose an asset freeze, travel ban and arms embargo on Gaddafi’s government. Eventually, as Libya became mired in a brutal civil war, Chinese authorities were forced to make the announcement that China was ending all of its commercial activity there. Over 35,000 Chinese citizens were evacuated from Libya in the first two months of 2011, and the number of Chinese businesses operating in Libya decreased by more than 45%. It is likely that Beijing’s decision to adopt a flexible stance on its non-interference doctrine with regard to Libya was motivated by its economic interests in the country.

Concerns about Beijing inconsistently using its non-interference principle to protect and further advance its interests have grown in recent years. For instance, during the 2019 pro-democracy Hirak movement in Algeria, Chinese officials did not miss the chance to reaffirm their support for Algeria’s political regime. When the European Parliament passed a resolution titled ‘The Situation of Freedoms in Algeria’ denouncing the regime’s detention and persecution of political opponents, human rights advocates and journalists, China’s Ambassador to Algeria, Lie Lianhe, backed the Algerian regime by stating that China opposed any ‘interference’ by foreign powers in the country. In Morocco and Tunisia, China’s policy of non-interference in domestic affairs appeals to both leaderships.

China’s significant footprint in the region is perceived as a threat to European powers’ interests.

In 2013 the Asian giant outranked France as Algeria’s leading trading partner, and Chinese multinationals have increasingly moved into sectors historically dominated by French players, such as civil engineering, telecoms and transport infrastructure. French national champions, including Total, Alcatel, Bouygues and Alstom, must now compete with Chinese giants who receive financing and assistance from the Chinese state. French President Emmanuel Macron warned developing nations during a visit to China in 2018 that the BRI might turn them into ‘vassal states’.

France, like other Western powers, has failed to provide an alternative to the BRI and the large funding it offers for infrastructural catch-up. The Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) launched in 2008 with the aim of promoting economic development, stability and integration between the two sides of the Mediterranean has faced much disillusionment among leaders of the Southern Mediterranean countries, as it is largely seen as an initiative that has failed to live up to its promises.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, China’s ‘mask diplomacy’ and later its ‘vaccine diplomacy’ consolidated its presence in the Maghreb. Beyond sharing medical expertise, personal protective equipment and vaccines with countries in the region, China started manufacturing its Sinopharm and Sinovac vaccines in Morocco and Algeria, respectively. Even though the pandemic was the death knell of several large-scale BRI infrastructure projects, China’s support to the region during the global health crisis has set the relationship to continue growing in a post-pandemic world. What follows delves into the nature of economic relations between China and the Maghreb.

(2) Sino-Maghrebi economic ties

(2.1) Trade

Trade between China and the Maghreb started increasing in the early 2000s, progressively making China a top-three import origin for all Maghreb countries. Between 2000 and 2020 total trade between China and the five Maghreb countries grew from US$742 million to reach around US$19.1 billion; yet the EU remains by far the Maghreb’s leading trading partner, with total trade volumes reaching around US$94 billion in 2020.

The Arab Spring had a negative impact on Chinese-Maghrebi economic relations. In 2010 China received 10% of Libya’s oil exports, accounting 3% of China’s total oil imports, or roughly 150,000 barrels per day. Libyan exports were impacted by the unrest following the 2011 toppling of Gaddafi. However, Libyan oil exports to China have resumed in recent years, reaching US$2.8 billion in value in 2021. This number accounts for a marginal 1.3% of China’s total imports in crude oil that year, which reached US$208 billion.

Unlike China’s trade with the Gulf, which is characterised by a trade surplus in favour of the Gulf states, data on Sino-Maghrebi trade indicate a significant trade deficit for North African countries. For instance, in 2021 Algeria’s imports from China reached US$6.7 billion, while Algeria’s exports to China averaged as little as US$1 billion. In the same year, Tunisia imported over US$1.8 billion in goods and services from China but sold no more than US$282 million in exchange. Trade figures with other Maghreb countries also indicate trade deficits with China, except for Mauritania which exported to China around US$1.7 billion in iron and copper in 2021 while importing as little as US$947 million in Chinese products and services.

Furthermore, the composition of trade between China and Maghreb countries reproduces patterns of unequal trade. High-value-added products like electronics, automobiles and phones constitute the lion’s share of Chinese exports to Maghreb countries, while oil, minerals and agricultural products dominate Maghreb exports to China. Energy resources occupy the bulk of Chinese imports from Libya and Algeria, while minerals and agricultural goods take an important place in Moroccan and Tunisian exports to China. In recent years, agricultural exports from North Africa have become more significant due to China’s growing demand for imported food. Morocco has increased its orange exports to China, becoming one of China’s major suppliers of oranges.

Overall, although Maghrebi consumers have welcomed the low prices of Chinese products, these same products have often outcompeted local manufacturers in the domestic market and other foreign markets such as the EU, further exacerbating the region’s high unemployment rates.

(2.2) Investment

Following Beijing’s adoption of its ‘going out’ strategy and accession to the WTO in 2001, many Chinese enterprises, both public and private, ventured to invest abroad, including in the Maghreb. Data released by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Commerce (MOFCOM) on Chinese Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) indicate that the Maghreb receives an insignificant share of China’s outward investment. As of 2021, Chinese FDI stock in the five Maghreb countries totalled US$2.2 billion, accounting for a negligible 0.08% of total Chinese FDI stock abroad for the same year, estimated at US$2785.15 billion.

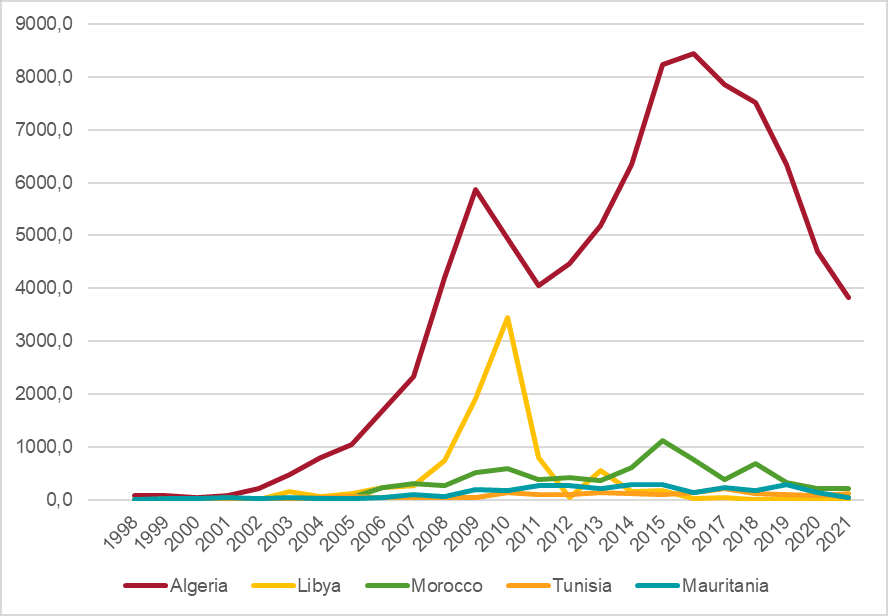

While China does not invest much in the Maghreb, its companies have secured large turnkey contracts for infrastructural building. Owing to their price competitiveness, Chinese firms have won large bids issued by local governments to provide services or build infrastructure in return for remuneration. Algeria’s East-West highway, Algiers’ new airport and the Great Mosque of Algiers all are conflated in the popular media and reports as Chinese investments but are, in fact, juicy contracts awarded to Chinese firms by the Algerian government. Between 2009 and 2019 Algeria became one of the most important markets in Africa for lucrative construction projects after granting an estimated US$70 billion in contracts to Chinese firms. Yet, since the drop in oil prices in 2014, Algeria’s appetite for infrastructural construction has decreased, leading to a drop in the value of contracts attributed to Chinese firms, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Gross annual revenues of Chinese construction companies in the Maghreb, 1998-2021 (US$ million)

Chinese firms have received criticism from local governments and citizens for mainly employing Chinese workers, limiting job opportunities in economies already struggling from high unemployment rates. However, private and public corporations have increasingly worked to enhance their reputation by increasing local hiring and putting in place programmes for training local staff.

For instance, in the ICT sector, Huawei has been notably active in establishing cooperation agreements with local universities and in training students across Maghreb countries. The Chinese tech giant has launched a Seeds for Future scholarship, which takes some of the brightest students from all over the world to Huawei’s headquarters in Shenzhen and offers them exposure to new technologies and immersion in Chinese culture. Huawei also organises large-scale ICT competitions, including within and among North African countries.

Furthermore, since establishing the BRI as the hallmark of its foreign policy, Beijing has indicated a qualitative shift in China’s engagement with the region.

The 2016 China-Arab policy paper released by China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs highlights its readiness to coordinate development strategies with Arab nations in accordance with their own needs, and to advance cooperation in the fields of science, technology, research and education, as well as in economic sectors like finance, telecommunications, renewable energy and the pharmaceutical industry, as illustrated by China’s manufacturing of its COVID-19 vaccines in the region. This qualitative turn bears the promise of more developmental spill-overs for Maghreb countries against the backdrop of low capital inflows from China into the region.

(3) Chinese soft power in the Maghreb

Beijing enjoys relatively high levels of support in the region. A 2020 survey from the Arab Barometer on ordinary citizens’ perception of China in the MENA region reveals that China’s influence in the Maghreb is seen as beneficial overall. Over 60% of Tunisians and Libyans said that they would favour stronger economic relations with China, against 49% of Moroccans. Interestingly, in Algeria, where China’s engagement is the most important in the Maghreb, only 36% of respondents said that they would favour stronger ties with China. This is likely to be tied to the negative reputation of some Chinese firms operating in the country, which are often seen to favour Chinese employees and to practice relatively lower labour and environmental standards than other foreign firms in the county.

While China’s own development model and its infrastructure-building and investments in the region largely contribute to China’s positive image both within elite circles and the people, its image is tainted among ordinary citizens for its authoritarianism and human rights abuses, especially against the Uighurs, a Muslim minority from Xinjiang, in north-western China. It is reported that China has forced as many as 1 million Uighurs into internment in Xinjiang. Meanwhile, governments across the Maghreb, similarly to other MENA governments, have remained silent for fear of jeopardising their economic interests with China. But beyond economic reasons, countries across the Maghreb have poor human-rights records themselves. Even Tunisia, the Arab Spring’s most promising democratisation story, is sliding back into authoritarianism.

Possibly the most successful aspect of China’s soft power in the Maghreb and the Global South more broadly is the so-called Beijing model, which promises rapid economic development without the democratic imperative. The post-Cold War liberal global order, described by Francis Fukuyama as ‘the end of History’, has been seriously challenged by this model. Ruling elites across the Maghreb find the model appealing as they attempt to hold their grip on power.

Some have argued that through the BRI China aims to expand autocracy globally and fight the liberal values at the heart of the current international order. So far, no substantial evidence suggests that China is actively working on exporting its model to other countries. Beijing is becoming a ‘normative power’, not by directly imposing its political/economic model, but by setting an example that other developing countries wish to mimic. As it stands, China seems more interested in forcing adjustments to the current global order than in radically overthrowing it altogether. In the foreseeable future it is likely that Chinese initiatives and institutions will continue to co-exist in complementarity with Western-dominated institutions.

If China has gained a strong foothold economically, politically and diplomatically in the Maghreb, its cultural influence is lagging far behind Western culture. People across the Maghreb tend to have scant knowledge of Chinese culture, language and traditions. Until recently, Algeria used to be host to one of the largest Chinese communities on the African continent, with an estimated 91,596at its peak in 2016. But despite this rather substantial number, there has been little social mixing with the local community due to the language barrier and the fact that Chinese workers tend to live in isolated compounds. Since 2016 the number of registered Chinese workers in Algeria has steadily declined to reach 10,219 as of 2021.

In its attempt to expand its cultural and linguistic influence, China has established Confucius Institutes in Tunisia and Morocco. These Institutes are modelled on Western cultural institutes such as France’s Institut Français, Germany’s Goethe Institute or the UK’s British Council. Although China launched its cultural institutes a century later, it is now second only to France when it comes to the number of its cultural institutes worldwide.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism had become an important way of developing cross-cultural awareness between China and the Maghreb. The booming number of Chinese tourists travelling overseas before 2020 had led some countries in the Maghreb to cater to the taste of Chinese customers in order to attract a greater share. For instance, Morocco removed in 2016 its visa requirements for Chinese citizens visiting the kingdom. Hotels in Marrakech have introduced Chinese meals to their menus, and hotels are adding Chinese TV channels to their TV subscriptions. This helped increase the number of Chinese tourists from 118,000 in 2017 to 200,000 in 2019. With the easing of COVID-19 travel restrictions in China in 2023, the number of Chinese tourists is expected to pick up again in the foreseeable future.

Conclusions

From Bandung’s anti-imperialist spirit to the BRI’s pragmatism, China and the Maghreb have built and sustained friendly relations. In recent years the Maghreb has gained geopolitical value in Beijing’s eyes due to its strategic location and its proximity to the European market. While China shows limited appetite for overthrowing the global international order, its greater engagement with the region can further affect European interests. For their part, Maghreb countries see cooperation with China as an opportunity to reduce Western influence and dependence on the EU and the US.

Despite much fanfare about the inherent advantages of South-South cooperation and win-win relations, Sino-Maghrebi relations reproduce the same patterns of unequal exchange observed in the region’s economic relations with European countries.

This is primarily due to the Maghreb’s low levels of diversification and sophistication. But the price-competitiveness of Chinese construction firms and their preferential access to government loans have helped the region catch up with much-needed infrastructure.

In a post-COVID-19 world, the sustained Chinese presence in the Maghreb will significantly affect economic growth, political systems, social cohesion, and national and regional security. Governments across the region should ensure that cooperation agreements with China entail more balanced connections, including closer cooperation in high-added value sectors, research and development, and people-to-people exchanges.

This discussion prompts the old debate about regional integration. Closer regional cooperation would help the Maghreb become more powerful and competitive, enabling each nation to better take advantage of China’s presence. Balancing out the uneven relationships with China requires moving beyond the current bilateral relations and strengthening the Maghreb’s integration. However, such integration remains elusive in the context of the ongoing Algerian-Moroccan enmity.

[1] By the Maghreb, this paper refers to Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya and Mauritania.