The average age at which young people in Spain leave the parental home and live independently is 30.3 years, four more than the EU average and the highest age of emancipation in the past 20 years (see Figure 1). More than 80% of the population aged between 16 and 29 live at home compared with an EU average of 68%.

Figure 1. Estimated average age of young people leaving their parental home, 2022

| Age | |

|---|---|

| Spain | 30.3 |

| Italy | 30.0 |

| Poland | 28.9 |

| EU average | 26.4 |

| Germany | 23.8 |

| France | 23.4 |

| Sweden | 21.4 |

Precarious and low paid jobs and the dire lack of affordable housing, particularly social rental accommodation, are the main factors behind this growing problem. The average age of emancipation in 2008 at the height of Spain’s economic boom before the onset of the country’s Great Recession, following the global financial crisis and the bursting of the country’s massive property bubble, was two years lower at 28.4.

These factors are also behind Spain’s low fertility rate of 1.3 children per woman, below the rate of 2.1 needed to replace the population. Without the influx of immigrants, the population would have shrunk massively over the past 20 years.

A report by the BBVA Foundation published last month makes for depressing reading. The average net salary of young adults is €1,005 a month, 35% lower than the average for the working population as a whole, and the average rent €944 (93.6% of their salary). Including additional costs of €138 a month (excluding food), such as electricity, these people need €1,082 to survive. One in five people under the age of 30 with a job is in poverty or at risk of social exclusion.

The only way they get by is by sharing accommodation –the average price of a room in a shared flat is €375 a month– with financial support from their family or by living in the parental home. In central Madrid, where I live, there is a growing trend of turning vacated bars and shops into tiny flats.

House prices have been rising at a much faster rate than salaries; by the end of 2023 they were almost back to their level at the peak of the real-estate bubble in 2008. Moreover, whereas someone born in 1955 could expect to be earning the average wage by the time they were 27, those born in 1985 did not achieve this until they were 34.

Social rental housing accounts for a derisory 1% of the total housing stock, the lowest rate in the EU, according to the latest comparative figures (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Social rental housing stock, 2020 (% of the total stock)

| % | |

|---|---|

| Netherlands | 34.1 |

| France | 14.0 |

| Poland | 7.6 |

| EU | 7.5 |

| Italy | 4.2 |

| Germany | 2.7 |

| Spain | 1.1 |

The Socialist-led minority coalition government promised last April to build 20,000 social housing flats on land belonging to the Defence Ministry, bringing the total number built or to be built to 183,000 since Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez first took office in 2018. According to the government only 1,600 social housing homes were built during the Popular Party government between 2011 and 2018.

The housing shortage is particularly acute in the city of Madrid (population 3.4 million), as it is in most European capitals. This could be eased by Madrid Nuevo Norte, a new district and business hub around the Chamartín train station, where around a third of the planned 10,500 apartments are to be publicly protected.

Obtaining a mortgage to get on the property ladder is way beyond the means of young adults unless they have parental help. The down payment is more than €50,000, the equivalent of more than four years’ salary. Getting to the end of the month is a struggle, let alone saving.

The worst off are the up to one million neither studying nor in employment (NEETs). The NEETs rate peaked at 22.5% in 2013 and in 2022 was down to 12.7%, not far off the EU average and much better than Italy, but still high (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Young people (aged 15-29) neither in education and training nor employment, 2022 (%)

| % | |

|---|---|

| Italy | 19.0 |

| Spain | 12.7 |

| France | 12.0 |

| EU average | 11.7 |

| Poland | 10.9 |

| Germany | 8.6 |

| Sweden | 5.7 |

| Netherlands | 4.2 |

At the opposite end are the well-educated, as exemplified by the appointment last month of Spain’s new Economy Minister, Carlos Cuerpo (43). He hails from Extremadura, one of the poorest regions. His maternal grandfather, who had begun working at the age of nine, was determined that his children would not suffer the same fate and would receive the best education possible. The Minister’s mother became a teacher and after marrying emigrated to Switzerland in search of a better life when Cuerpo was nine. On returning to Spain, Cuerpo went to university, gained a master’s from the London School of Economics, a doctorate in Spain and passed the highly competitive and demanding exam to become a government economist.

Young adults are much better educated today than 40 years ago. The higher the level of attainment, the better the employment prospect and the higher the salary. Half of those aged 25 to 29 have higher education titles (a degree or advanced vocational training), four times more than the proportion in 1980, but one quarter of those in this age group only completed their obligatory education, which ends at 16, the legal age at which students can leave school.

The early school-leaving rate has come down significantly since peaking at 31.7% in 2008, but at 13.6% in 2023 was still well above the EU average and the bloc’s target for 2030 of 9% (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Early leavers from education and training, 2022 (% of population aged 18-24)

| % | |

|---|---|

| Rumania | 15.6 |

| Spain (1) | 13.6 |

| Germany | 12.2 |

| Italy | 11.5 |

| EU | 9.6 |

| France | 7.6 |

| Poland | 4.8 |

| Ireland | 3.7 |

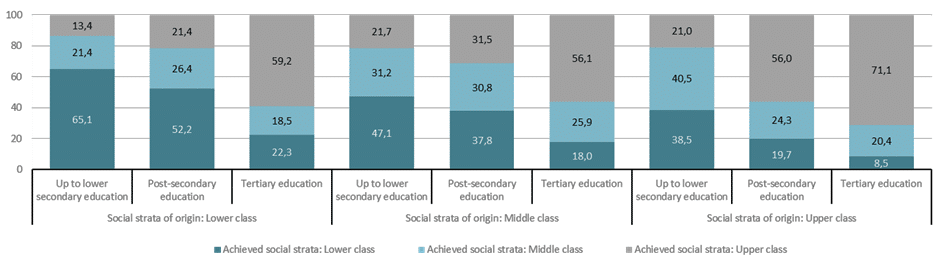

The advances in education in Spain over the past 40 years have been the driving force behind social mobility. Of those aged 25 to 29 from poor backgrounds who completed higher education, 60% moved up the social scale, as against 13% of those with just basic education. By the same token, 38.5% of those from well-off families who only completed their basic education dropped down the social scale (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Social mobility of young people in Spain, ages 25 to 29: occupied position based on social strata of origin and level of education, 2019 (%)

Spaniards are much better educated, but there are insufficient jobs commensurate with their abilities. The country has an over-qualification rate of 36%, the highest in the EU (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Over-qualification rate, 2022 (%) (1)

| % | |

|---|---|

| Spain | 35.9 |

| Ireland | 28.5 |

| EU | 23.5 |

| Italy | 22.3 |

| France | 21.6 |

| Germany | 20.0 |

| Poland | 19.7 |

| Sweden | 13.6 |

The latest labour reform, which came into effect in March 2022, is beginning to benefit young adults. It has substantially increased the number on permanent contracts, thereby reducing the temporary employment rate, a problem traditionally endemic among the young population, from 21% in 2022 to 16% at the end of 2023. The number of those on fixed discontinuous contracts (they only work during part of the year but their contracts are permanent) has skyrocketed.

A record 783,000 jobs were created last year, most of them in the services sector, which was bolstered by international tourist arrivals exceeding the pre-pandemic peak in 2019 of 83.5 million visitors by 1.6 million. Tourism generated 12.8% of GDP last year and was responsible for 70% of the growth in economic output of 2.5%, well above the 0.6% growth for the EU as a whole. Yet 2.8 million people are still unemployed (11.8% of the labour force, almost double the EU average).

The plight of young adults is rightly becoming a political issue, but their influence in the political sphere is reduced in a population that is fast ageing and where the voice of pensioners is much louder and heeded more by politicians. Those aged 16 to 29 today account for just under 15% of the population, down from 24% in 1995, while those over 55 account for 32% and are forecast to reach 42% in 2070.

Young adults rarely demonstrate if at all against their plight, while pensioners have not shied away from taking to the streets when cuts loomed (2018) or they demanded better pensions (2022). It would not be surprising if this changed.