Theme

Spain combines high levels of immigration with high unemployment rates and insufficient growth in per capita GDP.

Summary

Since the start of the 21st century, Spain’s population has grown by eight million, with the total population increasing from 40 to 48 million, a rise of 20%, double the growth rate experienced by the other countries that were members of the EU in 2000. All of this growth was due to immigration, as the birth rate continues to fall and is now lower than the death rate. At the same time, between 2000 and 2022 Spain’s per capita GDP has lagged behind that of the EU-15, due to the low productivity of its economy. The concentration of immigrants in low-skilled and poorly-paid jobs, along with their lower rates of employment, have led to an increase in rates of inequality and poverty.

Analysis

Immigration has had a greater impact on Spanish society in the first two decades of this century than any other phenomenon, influencing almost every important area of life, starting with the core of any society: its size, composition and evolution –its demography–. But immigration also affects many other areas of the social, economic and political landscape: the employment market, the welfare state, the pension system, inequality, poverty, productivity, wealth, housing, foreign policy, the party system and culture.

In just a few years, Spain has shifted from being a low-immigration country to having one of the highest rates of immigration in the EU, with the added difference that a process which began in central Europe 65 years ago (with countries such as Belgium, France, Germany and the Netherlands beginning to receive large numbers of immigrants in the 1960s) taking place over a much more concentrated period of around 25 years in Spain. Spain currently has immigrant population levels similar to Germany and Belgium, and higher than Denmark, the Netherlands, France and Italy.

The foreign-born population in Spain now accounts for 18% of total population, but accounts for a far higher proportion of the population of active age: for every 100 native-born Spaniards at the age of greatest labour market participation (25 to 49 years), there are 38 immigrants. Many sources present lower figures because they only identify those without Spanish nationality as immigrants. However, many of the immigrants who have come to Spain in previous years have obtained Spanish nationality, which is relatively quick and easy to do for Latin Americans (the bulk of immigrants in Spain). Immigrants who obtain Spanish nationality acquire rights they previously lacked (such as the freedom to enter and leave the country without restrictions, and the right to vote in all elections) but for purposes of analysis they should still be considered immigrants according to the definition used by the Population Division of the United Nations: a person who lives in a different country to the one in which they were born. The Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE) currently identifies 2.5 million people born abroad who are resident in Spain and hold Spanish nationality (Padrón 2022).

Spain’s population has grown by eight million since 2000, an increase that is the result entirely of the arrival of immigrants, with a net migration rate far higher than that of other EU members. In 2000 the population of the 14 other Member States of the EU was 334 million. By 2023 the population of those countries had risen by 10%, to 368 million, while Spain’s population had grown by 20%, double the rate of the rest. Since the lifting of travel restrictions at the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of immigrants in the country has grown by more than 600,000 per year, a faster rate than in previous periods. From January 2022 to October 2023, the most recent figures from the Spanish National Statistics Institute reveal that the number of people born abroad and resident in Spain rose by 1,035,000.

At the same time, the birth rate has continued to fall throughout this period and the number of deaths now exceeds the number of births, meaning that the rate of natural increase (RNI) is negative.

In contrast with countries that have applied selective immigration policies, during the first decades of the 21st century Spain has applied a policy of tacit liberalisation, which has permitted the annual arrival of hundreds of thousands of immigrants, many of whom have stayed for years on an irregular basis before legalising their situation through either ordinary or extraordinary regularisation procedures. This effective if undeclared policy of informal liberalisation has particularly benefited those from Latin American countries, the majority of whom are exempt from visa controls.

The majority of the immigrants received by Spain –excluding those from European countries with similar or higher levels of per capita GDP– have, on average, a low or medium level of education, particularly marked in the case of migration from Africa, and have primarily found employment in the service sectors (shops, hospitality, distribution, transport and personal services), with lower percentages employed in construction and agriculture. The availability of this new influx of people of working age fuelled the property boom, which would have been impossible without the existence of this extra labour, and is now driving a service-based economy.

During the same period over which this population growth occurred, from 2000 to 2022, Spain’s per capita GDP rose by €12,300, France’s by €14,300, Germany’s by €20,400, Belgium’s by €22,400 and the Netherlands’ by €30,800. Spain has lagged further behind the richest countries of the eurozone, and the country’s per capita GDP remains lower than that of the other countries who were already members of the EU (then the European Community) when Spain joined in 1986. The low productivity of the Spanish economy is often identified as one of its biggest structural problems, and the existence of an abundant supply of low-skilled workers incentivises investment in services with low added costs.

Immigrant participation in industry –the most productive economic sector– is very low (excluding construction and the food and agricultural sector, such as meat processing), and the same is true of more highly skilled services (such as banking and research). In general, immigrants are concentrated in sectors of the Spanish economy that are characterised by lower productivity, worse employment conditions and lower salaries. As the report on the Integration of the Foreign Population in the Spanish Labour Market (Mahía & Medina, 2022) confirms, the average salaries of foreigners born in the Americas –basically, Latin Americans– are 37% lower than those of Spaniards, while they are 34% lower in the case of Africans and 17% lower in the case of Europeans. And the gap is even greater for women.

The report also found that immigrants have lower employment rates than the native-born population when the most active cohorts, between ages 25 and 64, are compared, and thus have higher rates of unemployment. The most recent INE Active Population Survey (4Q23) recorded an unemployment rate of 15% for male non-EU immigrants, compared with a rate of 10% for Spanish men and 11% for those from other EU countries. The differences are far higher for women: 22% for non-EU immigrants, 12% for Spanish women and 17% for women from other EU countries).[1]

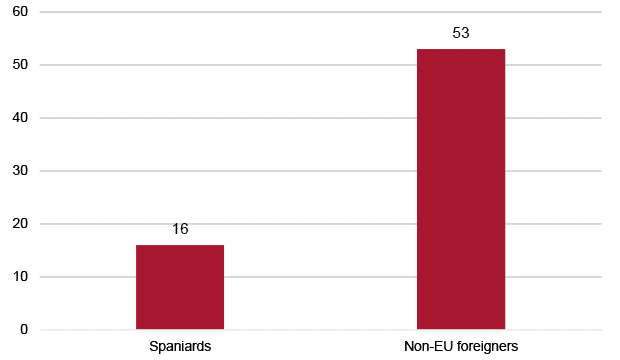

The combination of lower employment and the concentration of those with jobs in low-salary positions means that a high proportion of the immigrant population is at ‘risk of poverty’ or even in a position of ‘material deprivation’. Some 53% of foreigners resident in Spain and originating from non-EU countries were at risk of poverty in 2022, compared with 16% of Spaniards, according to the latest Living Conditions Survey (INE). The percentage of non-EU foreigners in a situation of ‘material deprivation’ was much higher than for Spaniards, with almost two thirds of these immigrants in a situation where they would be unable to face unexpected expenses.[2] Although no statistics are published on the origin of beneficiaries of either public assistance (national, regional or local) or private assistance (Cáritas, Red Cross, food banks, canteens, etc) specifically targeted at those in conditions of poverty, it is clear that immigrants more frequently find themselves in this situation.

Figure 2. Percentage of population at risk of poverty (16 years and older)

The inequality reflected by this data means that Spain, together with Italy, heads the inequality ranking of EU-15 countries with a Gini index of 34.9. In the EU as a whole, the Gini indexes range from 23.2 points for Slovakia to 40.5 for Bulgaria.

Although the employment rate for immigrants is lower than for Spaniards, the vast majority of new jobs created in the private sector in recent years have been occupied by immigrants.[4] These phenomena are compatible because of the high number of new immigrants arriving each year, in sufficient quantity both to fill new positions and to fuel unemployment. As Josep Oliver, an economist specialising in the labour market and immigration, explains, ‘between 70 and 89% of new employment in Spain and 100% in Catalonia is covered by immigrants’, and he warns that ‘if we don’t get this right we’ll have social problems like those we’ve seen in Ripoll because there is downward pressure on the labour market’. [5] Observers of the labour market point to the low added-value and low salaries of the new jobs created in recent years.

There is a real danger that the medium or low levels of education of immigrants received by Spain will become a chronic problem, in light of the educational results of second-generation immigrants, who have far higher school drop-out rates than those with native-born parents, condemning many of these adolescents to a future of unemployment or poorly paid, precarious work. Overall, 33% of students born outside Spain drop out before completing compulsory schooling at age 16, compared with a figure of 16% for native-born students. Drop-out rates are far higher among male than female immigrants, and particularly high among those from certain countries of origin.[6]

Spain has not made sufficient investments in strengthening primary and early secondary education to counteract the underlying inequality suffered by many children of immigrant families –parents with low levels of education, lacking the time or ability to help their children, unable to afford the private classes that help many children of native-born parents, etc–. The results of the latest PISA tests, organised by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), show that students of immigrant origin in Spain on average score 32.5 points lower in maths than non-immigrant students, the equivalent of a delay of approximately one and a half years. These are averages, which do not reflect the huge difference between immigrant children depending on the country of origin of their parents (the data group together students of Chinese, French, British, Ecuadorean, Rumanian, Moroccan and Venezuelan origin.) This reduced educational success is a threat to the occupational and thus the social integration of a significant portion of these ‘second generations’, a segment whose aspirations to living conditions similar to those of their native-born contemporaries will be frustrated. And this predictable frustration represents a threat to political and social stability, in the context of the growing polarisation of public opinion with respect to immigration.

Conclusions

The tacit liberalisation of immigration practised by successive Spanish governments –of all political stripes– since the start of the 21st century, has led to a sharp rise in the immigrant population, which has grown very rapidly in comparison with other European countries. The 20% increase in total population has not been accompanied by any narrowing of the per capita GDP gap with our western European partners, because most of this new population is employed in low productivity sectors, and because their employment rate is lower than that of the native-born population.

At the same time, there has not been a debate in Spain about what kind of immigration the country should attract, nor about how to deal with problems related to the high educational drop-out rates of second-generation immigrants, and the threat this poses in the future, the impact on the health system, how the growth of low-employment jobs affects the pension system as a result of lower contributions, about the political problems that may arise from increased inequality and poverty, or how to interpret the unemployment rate of the native-born population in the light of data on the growth of immigrant employment. More generally, there is a need for reflection on the relationship between immigration and the economic and social model the country wants.

The migration debate has been hijacked by issues that are more visible in the media, such as the allocation of migrants who arrive by sea, the question of unaccompanied minors and irregular migration in general. However, migrants who arrive on tourist or student visas or without being subject to any visa requirements at all are more significant both in terms of their total numbers and their long-term impact on Spanish society and the Spanish economy, and we should pay more attention to them.

[1] These figures record those with dual nationality as Spanish (primarily, Latin Americans who have obtained Spanish nationality).

[2] The statistics from the Living Conditions Survey of 2022, the most recent, reflect data from the previous year (2021), when Spain had not yet recovered the level of employment prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. It seems likely, then, that current data would show lower levels of poverty both for immigrants and Spaniards, although the difference between the two groups would probably be similar. It is also important to note that the survey does not distinguish between immigrants and the native-born but between foreigners and Spaniards, which flattens the differences between the two groups.

[3] The ‘population at risk of poverty’ comprises those whose annual income is below 60% the median of the national total. Despite the name, then, it is a measure of inequality rather than of poverty.

[4] See https://www.lavanguardia.com/economia/20230717/9113687/mayoria-nuevo-empleo-creado-espana-cubre-inmigrantes.html. According to the article, 95% of the new jobs created between the first quarter of 2022 and the first quarter of 2023 were occupied by immigrants. See also https://cincodias.elpais.com/economia/2023-07-11/los-trabajadores-extranjeros-copan-el-77-del-empleo-creado-en-el-ultimo-ano.html. The presence of immigrants in the public sector is still limited because access is restricted on the basis of nationality.

[5] Ripoll (a municipality in the province of Girona in Catalonia) is governed by a party, Aliança Catalana, which combines support for Catalan independence with anti-immigration and Islamophobic discourse.

[6] S. Carrasco, J Pamiés & L. Narciso (2028), ‘Abandono escolar prematuro y alumnado de origen extranjero en España. ¿Un problema invisible?’, Anuario CIDOB de la Inmigración.