Spain started to be changed beyond recognition after the Socialists’ victory in 1982, but pressing issues remain.

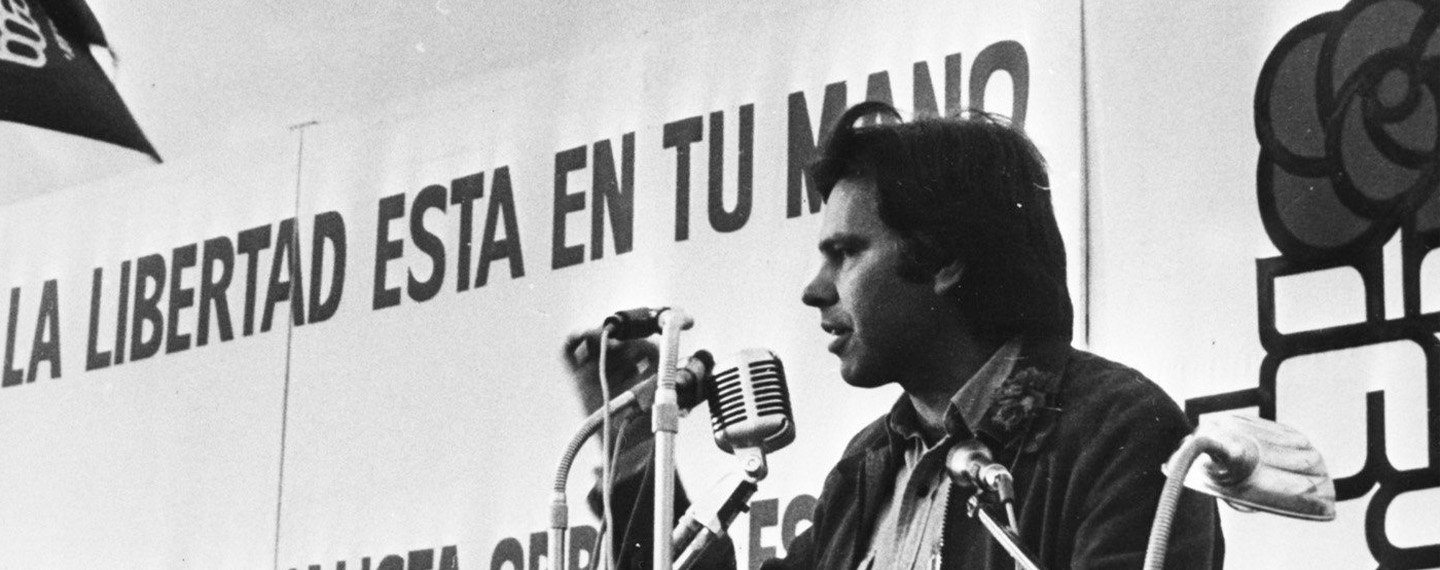

Spain began to be profoundly transformed 40 years ago last month when the Socialists (Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE), led by Felipe González, won a sweeping victory at the general election on 28 October under the catchy slogan Por el cambio (‘For change’), which perfectly caught the nation’s mood.

The 10.1 million votes cast for them on 28 October (48% of the total and 202 of the 350 seats in parliament) were almost double those for the conservative Popular Alliance (Alianza Popular, AP) and compared with just four seats for the Spanish Communist Party (PCE), the main opposition to the Franco regime during which the Socialists barely existed.

Today, the Socialists in a minority coalition government with the hard-left Unidas Podemos (the first since the Second Republic in the 1930s) have 120 seats. Since 1982 they have been in power during 25 of the past 40 years, alternating with the Popular Party (Partido Popular, PP) as the PA later became (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Results of general elections, 1982-2019, for the Socialists and Popular Party (% of total votes) (1)

| 1982 | 1986 | 1989 | 1993 | 1996 | 2000 | 2004 | 2008 | 2011 | 2015 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSOE | 48.3 | 44.1 | 39.6 | 38.8 | 37.6 | 34.7 | 42.6 | 43.6 | 28.7 | 22.0 | 28.0 |

| PP | 26.5 | 26.0 | 25.8 | 34.8 | 38.8 | 45.2 | 37.6 | 40.1 | 44.6 | 28.7 | 20.8 |

Figure 2. The three Socialist governments since 1986: basic indicators in the last year of their administration except for that of Pedro Sánchez (the latest available)

| González gov. (1982-96) | R. Zapatero gov. (2004-11) | Sánchez gov. (2018-) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population (mn) | 39.9 | 46.7 | 47.4 |

| Foreign population (1) | 637,085 (2) | 5.1mn | 5.4mn |

| Per capita GDP (current prices US$, PPPs) | 19,118 | 31,872 | 41,838 |

| Fertility rate | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Unemployment rate (%) | 22.1 | 21.4 | 12.6 |

| Fiscal balance (% of GDP) | -5.8 | -9.7 | -6.8 |

| Public Debt (% of GDP) | 65.4 | 69.9 | 116.1 |

| Tax revenue (% of GDP) | 31.8 | 32.0 | 36.6 |

| Imports of goods (% of GDP) | 19.5 | 25.4 | 29.4 |

| Exports of goods (% of GDP) | 17.3 | 20.7 | 26.8 |

| Outward FDI stock (US$ bn) | 41.5 | 656.5 | 600.8 |

| Inward FDI stock (US$ bn) | 110.2 | 628.9 | 819.7 |

| Early school-leaving rate (% of population 18-24) | 31.4 | 26.3 | 13.3 |

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | 78.2 | 82.2 | 83.0 |

| Social protection spending (% of GDP) | 21.5 | 25.5 | 24.1 |

| International tourists (mn) | 55.0 | 99.2 | 31.1 |

| Number of cars (mn) | 14.7 | 22.3 | 24.5 |

The Socialists won power seven years after the death of the dictator General Franco and almost two years after a coup defused by King Juan Carlos, an action that earned Franco’s appointee his spurs as a democrat. Another coup, meant to take place the day before the 1982 election, was stymied.

Sabre rattling in the army was just one of the many problems the Socialists faced when they took office amid a perfect storm. The Basque terrorist group ETA killed 40 people that year (by the time it stopped killing in 2010 the death toll was 854); a severe economic crisis sparked a devaluation of the peseta; Rumasa, the largest private group on the verge of collapse, had to be expropriated; a scalpel was wielded on highly uncompetitive industries such as steel and shipbuilding; and unemployment rose in some months by 100,000 (making a nonsense of the Socialists’ campaign promise to create 800,000 new jobs in its term in office).

At the same time, the expectations raised by the Socialists’ electoral campaign were high and were frustrated. The largest general strike in Spain in the last 40 years, followed by 8 million workers and called by the Socialist UGT and the Communist CCOO, occurred in 1988 under the Socialists.

Gonzalez’s deputy, Alfonso Guerra, liked to say that ‘Spain will be so changed as to be unrecognisable’ (his actual words, based on a popular saying, were far cruder). This is true but, to be fair, Spain’s move to democracy and modernisation began not under González but under the Union of the Democratic Centre (Unión de Centro Democrático, UCD) of Adolfo Suárez (1977-81), the first Prime Minister freely elected since before the Civil War. For example, social protection spending rose more under the four years of the UCD (from 12.9% of GDP to 17.7%) than under 14 years of the Socialists (from 17.7% to 21.5%).

The Socialists consolidated democracy; created a system of autonomy for the 17 regions; realised Spain’s long awaited entry into the European Economic Community (EEC); engineered a U-turn in their commitment to leave NATO (at the time Spain was the only EEC country not a NATO member) and endorsed in a referendum in 1986 the membership decided by the previous government; universalised public health and pensions; raised the school-leaving age from 14 to 16; and invested heavily in infrastructure. Today, Spain’s high-speed rail network is the longest in Europe and the second in the world after China. ‘Work, work and work: morning, afternoon and night’, recalled Joaquín Almunia, who, aged 34, was the Labour and Social Security Minister.

Before he took office, González had shed the Socialists’ ideological baggage as a Marxist party in order to occupy the social-democratic ground like similar parties in Germany and the Nordic countries. This boosted the Socialists’ electability. González was flexible on tactics and inflexible on principles, epitomised by his citing of something the Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping famously said: ‘It doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice’. He also accommodated the pro-Republic party, founded in 1879, to the monarchy. King Juan Carlos believed that Spain’s democracy and the monarchy would not be secured until the left was in power.

González was an impressively effective Prime Minister, though he hung on to power for too long. His fourth government (1993-96) was marred by numerous corruption scandals, making a mockery of the Socialists’ slogan of ‘one hundred years of honesty’. The most damaging case was that of Luis Roldán, the first civilian head of the Civil Guard and tipped to be the Interior Minister, who fled Spain after he was dismissed from his post amid allegations of amassing a personal fortune, largely from kickbacks on the construction of Civil Guard buildings. He was captured in Laos and sentenced to 31 years in prison.

González’s priority was to make Spain function like any other ‘normal’ EEC country. His legacy is, on balance, very positive. However, in areas, such as the civil service and the justice system, Spain still does not function today as well as it should.

The Socialists’ promise to create a professional civil service was not realised, and neither has the PP achieved this. Political affiliation plays too much of a role in staffing the higher levels of bureaucracy at all levels of government (central, regional and municipal). Spain is one of the very few OECD countries where all or a high proportion of positions change systematically in the top two echelons of senior civil servants (D1 and D2 levels) after the election of a new government. In 17 of the 38 OECD countries (Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Ireland, Japan, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, the UK and the US) there is no or very little turnover in any of the four levels of senior civil servants when there is a change of government. Politically motivated turnover in the civil service erodes trust in public institutions, undermines the professionalism of civil servants and tends to make them choose political sides in order to advance their careers.

The justice system works at a snail’s pace –court cases can take years to come to trial (the backlog is huge) and the Constitutional Court’s rulings are painfully slow (four years in the case of the 2010 landmark ruling on the PP’s appeal against the Catalan statute and nothing yet on abortion, presented in 2010)– and the four-year political wrangling over renewing the General Council of the Judiciary (Consejo General del Poder Judicial, CGPJ) is a disgrace. The CGPJ, which plays a supervisory role and also appoints judges to the Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court, has been operating with an expired mandate since 2018. There are dozens of pending appointments in other judicial bodies, such as the Supreme Court.

In 1985 the Socialist government required all 20 CGPJ members to be appointed by parliament and no longer by the legal profession. At the time, this was understandable as many judges were regarded as tainted by the Franco era, but it sparked partisan horse-trading over the institution (something that afflicts other bodies colonised by politicians). The PP was happy to go along with the new system of appointments until it lost power in 2018, and with the Socialists back in power since that year it says ‘judges should be chosen by judges’. The Socialists are prepared to do this once a new CGJP is formed under the prevailing rules. European Commission exhortations to resolve the CGPJ have so far got nowhere. The impasse over the CGCP has dented public perception of judicial independence: Spain ranks 22nd out of 27 EU countries in this matter.

The main reason for Spain’s relegation in the EIU’s 2021 Democracy Index under the Socialist-led minority government of Pedro Sánchez from ‘full democracy’ to ‘flawed democracy’ was a downgrade in the score for judicial independence related to political divisions over the appointment of new judges to the CGPJ. Another reason was the litany of corruption cases. The Bárcenas corruption scandal, named after the former PP treasurer, which broke out in 2013, blew open that party’s illegal financing methods. The case is still ongoing. Spain came close to being reclassified as a ‘flawed democracy’ after its score fell in 2017 during the PP government of Mariano Rajoy over its botched handling of the unconstitutional referendum in Catalonia for independence.

The financing of political parties also leaves a lot to be desired. With the advent of democracy after Franco’s death and free elections, rules were established for state funding of parties, allocated on the basis of representation in the upper and lower houses of parliament and the share of seats in the previous election. Other financing sources are bank loans (sometimes never paid back), funds from companies, laying parties open to political favours and corruption, and donations. Parties are required to keep accounts, overseen by the Court of Auditors, which must be made public and must reveal the identity of donors (allowed to be anonymous between 1987 and 2007). The Court, however, is a toothless body (its 12 members are appointed by parliament with a majority of 3/5 for nine years and cannot be regarded as neutrally political people).

The Court’s reports on parties’ financial statements are published with considerable delays of up to five years, which makes it difficult for the judicial system to conduct any monitoring since most infractions of the regulations discovered are by then prescribed under the statute of limitations (five years for very serious offences, three for serious and two for minor ones). The latest report covering 2017 was published last February!

The Socialists, given their absolute majorities in three of their four governments, could have begun to tackle the issue of reparations for the victims of the Civil War, particularly the issue of mass graves, and the subsequent Franco dictatorship, instead of letting it fester until the 2007 Historical Memory Law approved by the Socialist government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero and the more broader 2022 Democratic Memory Law of the current Socialist-led government of Pedro Sánchez. It was not until 2019 that Franco’s remains were removed from the ‘Valley of the Fallen’ mausoleum (officially renamed Valle de Cuelgamuros in October of this year) outside Madrid, a monument that continues to be maintained by the state.

In retrospect, this is easy to say as González had far more pressing priorities and at least until his second government, with Spain firmly in the EEC, he could never be sure how the armed forces would react and the Francoist right in general. Better perhaps to let sleeping dogs lie. But whereas González, whose father experienced the Civil War, wanted to lay to rest the ghosts and divisions of the Civil War, the policies of Zapatero and Sánchez, the grandsons of that conflict, have revived them and sparked culture wars.

Lastly, Spain is still not a very transparent country. To the bane of historians, in particular, Spain never declassifies official documents, even decades after the events to which they refer. Spain’s Official Secrets Law still dates back to 1968 during the Franco regime. The draft of a new law is almost equally restrictive, enabling the government to keep records under wraps for up to 50 years or forever, compared with 25 years in the US, 20 in the UK and 15 in Italy.

As a result of these and other factors, distrust in political parties, parliament and the government has increased substantially over the past 15 years and is higher than the EU average (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Spain and the EU: trust in political parties, parliaments and governments, 2006-21 (%)

| 2006 | 2012 | 2016 | 2018 | 2020 | 2021 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political parties | Spain | Trust | 31 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 8 |

| Don’t trust | 59 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 90 | 90 | ||

| EU avg. | Trust | 22 | 18 | 16 | 19 | 21 | 18 | |

| Don’t trust | 71 | 78 | 78 | 77 | 75 | 82 | ||

| Parliaments | Spain | Trust | 41 | 11 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 18 |

| Don’t trust | 46 | 82 | 77 | 81 | 76 | 76 | ||

| EU avg. | Trust | 39 | 28 | 32 | 35 | 35 | 35 | |

| Don’t trust | 53 | 66 | 35 | 60 | 60 | 59 | ||

| Governments | Spain | Trust | 44 | 13 | 19 | 17 | 20 | 22 |

| Don’t trust | 45 | 83 | 77 | 81 | 74 | 75 | ||

| EU avg. | Trust | 35 | 28 | 31 | 34 | 36 | 37 | |

| Don’t trust | 58 | 67 | 64 | 61 | 60 | 59 |

The political scene today is far more fragmented than during the González era, with three new parties in parliament since 2015 –the would be-centrist Ciudadanos (Cs), the hard-right VOX and the hard-left Unidas Podemos. The next general election has to be held by the end of 2023. The days of absolute majorities like those of González’s first two governments do not look as if they will return.

Image: Felipe González, leader of the Socialists (PSOE) in Spain, giving a speech at a rally in Spain (1977). Photo: Anefo (Wikimedia Commons / CC0).