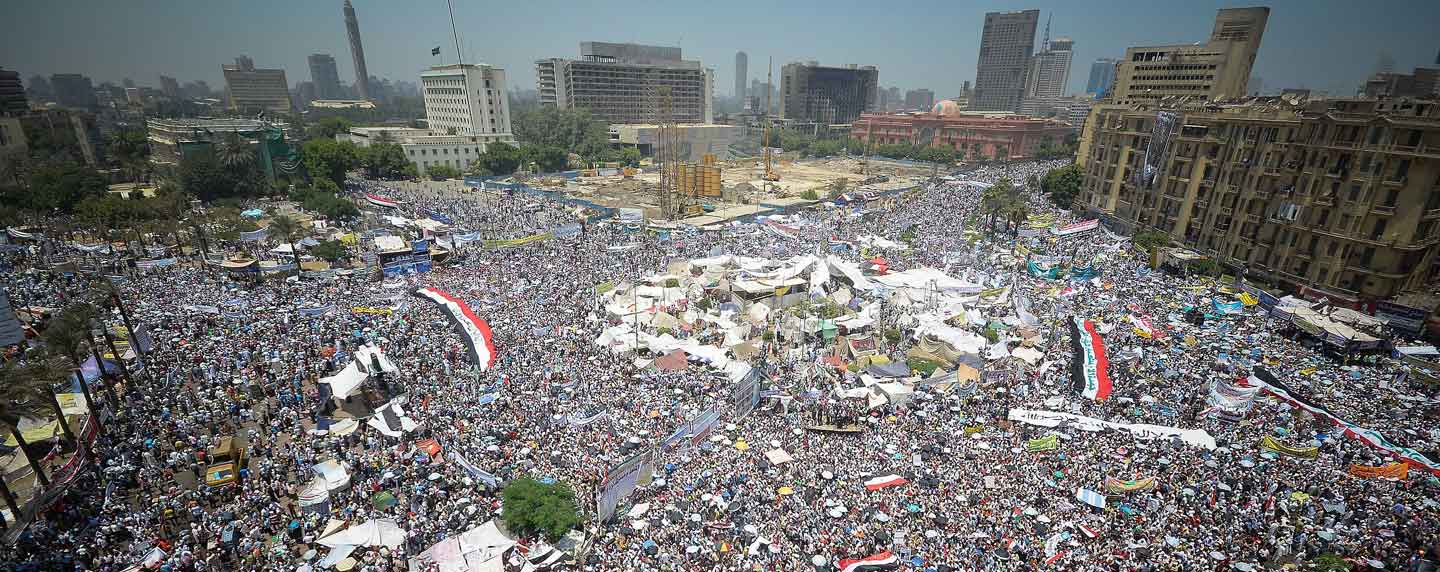

In the past decade, the EU’s Arab neighbourhood has been the scene of two waves of popular uprisings against ruling regimes. The first, in 2011, was widely covered by the world media and triggered destabilising processes that continue to this day. Its epicentres were Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Syria, although it was felt throughout the Maghreb and the Middle East, including the Arabian Peninsula. The second wave occurred in 2019 in Algeria, Lebanon, Sudan and Iraq. This wave received little attention and caused less change than the previous one, probably because it was brought to a grinding halt by the lockdowns caused by the pandemic, but it was no less important as a reminder of the deep, unresolved socio-political problems across the region.

Over the past decade, the narrative has spread in European public opinion that attempts to support democracy in Arab countries have been in vain. A sense of fatigue mixed with frustration has become widespread. This has led to a proliferation of discourses advocating that the EU should focus on its interests and maintain transactional relations with Arab regimes, for which Europe would do well to abandon the democratisation agenda. The success of this narrative is very surprising, as one has to ask whether the EU had really focused its relations with its southern neighbours on the promotion of democratic principles and values and the respect for human rights. The answer is an irrefutable no.

Over the past quarter century, the European bloc has been a pro-status quo actor in its southern neighbourhood, favouring a model of authoritarian stability. The reforms that have been undertaken have not led to the emergence of new democracies. In fact, in more than half a century only one new democracy has emerged in the southern Mediterranean: Tunisia. It was the result of a popular mobilisation in 2011 against a kleptocratic regime, without the EU having much say. In the following years, Tunisia drafted a democratic constitution, free and transparent elections were held and there was a peaceful alternation of power.

Unfortunately, the political transition did not bring economic improvements and the population, frustrated and hopeless, opted for an authoritarian President who has derailed the democratic experience. All this under the EU’s impassive or impotent gaze.

Signs abound today that the current balance between states and societies in several Arab countries is unsustainable. There are sufficient reasons to affirm that socio-economic challenges are growing at a much faster pace than the solutions required. From the start of the so-called ‘Arab Spring’ in 2011 to the present day, the population of the 22 Arab countries has grown from 360 million to 450 million (in 2001 it was 285 million and is projected to exceed 600 million by 2050). Population growth is at 1.9%, compared with the world average of 0.9% and 0.2% for the OECD. Two thirds of the current Arab population are under 30 years old (in other words, 300 million Arabs were born after 1992). One third of the total is under 15 years old (150 million were not yet born in 2007). The absolute majority of Arabs today live in countries mired in violent conflict, under occupation or ruled by highly authoritarian regimes.

It is estimated that up to 65 million new jobs would have to be created in the Arab region by 2030 to reach labour participation levels similar to those in middle-income countries. In addition, 64% of total employment in the Arab region is informal, with poor working conditions and limited job stability. The current context does not seem ideal for creating the conditions for such a leap. In the Arab region as a whole, policies to contain inflation could put pressure on already weak fiscal accounts, worsen financing conditions, provoke capital outflows and slow growth.

Successive disruptions over the past decade (regional conflicts, waves of refugees, the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, food insecurity, inflation and prospects of global recession, etc) are increasing pressures on many Arab countries. This is happening without these countries having addressed many of the pre-existing challenges, particularly in areas such as unemployment, innovation, competitiveness, private sector development and, above all, good governance and the establishment of modern and transparent institutions. This has led to increasing –and alarming– levels of indebtedness. Lebanon, a country suffering from multidimensional collapse, already declared itself in default in March 2020, while countries such as Tunisia and Egypt (the latter with over 100 million inhabitants) are at risk of economic collapse.

Arab citizens are increasingly less hopeful about the future of their countries in economic and political terms. This trend is clear in successive waves of the Arab Barometer’s regional opinion polls. Significantly, in the 10 Arab countries surveyed in 2020-21, a majority of respondents considered democracy to be the best system for governing their countries, despite its limitations. However, a widespread trend in the region is that authoritarian regimes feel strengthened, repress more forcefully, violate human rights more and reverse the timid democratic gains of previous decades.

The question that every European leader must ask today is not the one at the top of this article, but rather: ‘What options will the EU have left when the Arab revolts return?’. If regimes challenged by their peoples choose to crack down hard on them, will the EU continue to deal with these regimes on purely transactional terms? If so, how would this be perceived by Arab societies that have seen European countries turn in favour of Ukraine under the pretext of upholding democratic values and protecting civilians from tyranny and aggression?

Elcano Comments

This is a new initiative of the Institute that aims to offer analyses by experts on topics that are within the scope of our research agenda. They are published on no regular basis but as opportunity arises in accordance with the advice of the broader academic community in cooperation with the Elcano Royal Institute.

Image: A large crowd gathers in Tahrir Square in Cairo (Egypt) during protests in July 2011. Photo: Ahmed Abd El-Fatah from Egypt (Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0).