Spain’s economy is growing briskly, largely powered by foreign workers. These workers, particularly in the hostelry, construction, agricultural and social care sectors now account for 14% of total jobholders registered in the social security system. The foreign-born population surged from less than 1% of the total population in 1975 to 19% (9.4 million people) by the end of 2024.

But for immigration, Spain’s rapidly ageing population would hardly have grown, as the fertility rate of 1.12 children is well below the replacement rate (2.10) at which population levels would be maintained. In 1996 the United Nations forecast that Spain’s population would fall sharply by 2050 from almost 40 million to around 28 million. Most of the 8.2 million rise between 2000 and 2024 to 48.8 million was due to net international migration. Of the five most populous EU countries, Spain’s population has increased by far the most in relative terms (+20.2%) over the last 24 years (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Population, 2000-24 (mn)

| 2000 | 2024 | % change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2024 | % change | |

| France | 60.9 | 68.5 | +12.4 |

| Germany | 82.3 | 83.5 | +1.4 |

| Italy | 56.9 | 58.9 | +3.5 |

| Poland | 38.2 | 36.5 | -4.4 |

| Spain | 40.6 | 48.8 | +20.2 |

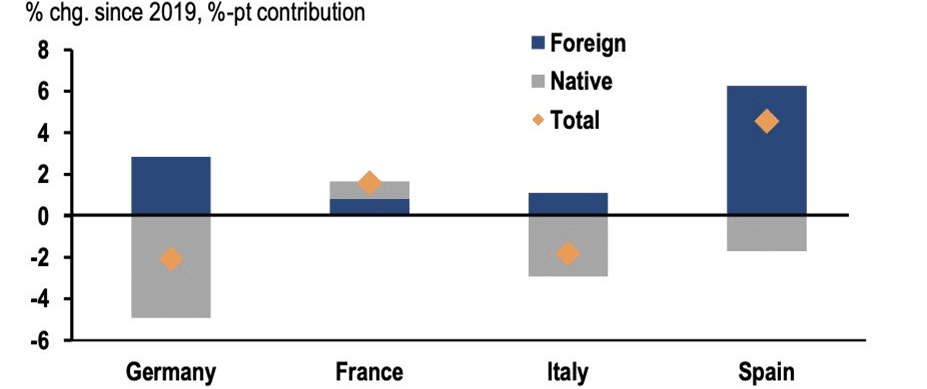

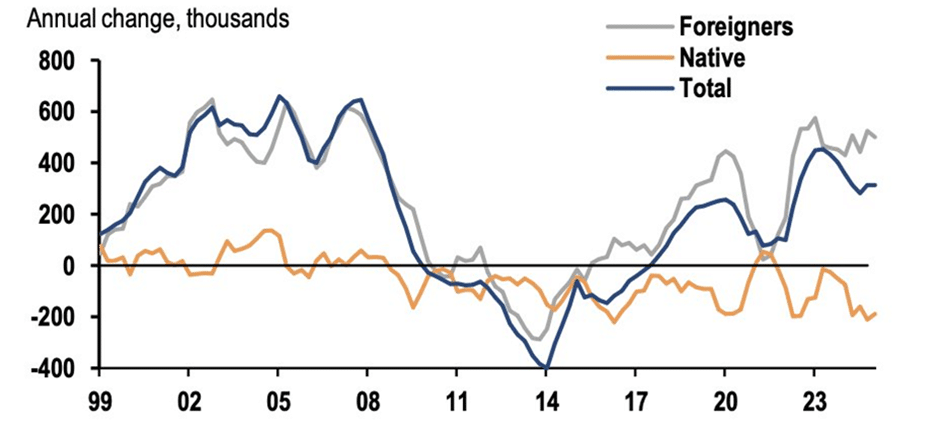

Meanwhile Spain’s economic growth has consistently outpaced that of the EU as a whole for the past three years: 3.2% in 2023, 2.9% in 2024 and around 2.6% in 2025 (EU averages of 0.4%, 1.1% and 1%, respectively). Foreigners are driving the increase in the working-age population much more than in the other three large EU economies (see Figures 2 and 3). The unemployment rate (10.3%) is the lowest since 2007 (27% in 1Q13), though almost double the EU average.

Figure 2. Working age population (15-64 years)

Figure 3. Spain: working age population, 15-64 years

If the hard-right VOX’s call for mass deportation of immigrants ever materialised (which it will not) the economy would collapse. That call, which provoked widespread outrage, was made in July by Rocío de Meer, the party’s spokesperson for demographic emergency. She suggested that only the deportation of 8 million immigrants and their children would permit Spain to ‘survive as a people’.

Santiago Abascal, VOX’s leader, rowed back on what was said (and recorded), insisting that only immigrants who committed crimes, sought to impose an ‘alien religion’ (an implicit reference to Islam) or mistreated women would be deported. There are more than one million Moroccans in Spain, including those who have acquired Spanish nationality.

Central-bank heads who gathered at Jackson Hole, Wyoming, last month sounded a warning bell over labour shortages in many developed economies that, in the context of historically low birth rates and longer life expectancy (Spain’s is one of the world’s longest), can only be solved by an influx of foreign workers.

Immigrants have not taken jobs away from Spaniards; many of them arrived during the country’s 1997-2008 economic boom and did the work that Spaniards were less inclined to do. To some extent, this explains why Spaniards are predominantly welcoming of immigrants. Also, many Spanish families have relatives who emigrated in the 1950s and 1960s, helping them to view migrants with greater understanding and sympathy and to feel relatively comfortable with them. Public opinion on immigration stands out as notably positive in the European context. According to the 2024 European Social Survey, Spain’s score –on a scale from 0 (very bad) to 10 (very good)– was 6.2.

A very large number of immigrants (47% of the total at 1 January 2024) are Latin American and hence usually share the same Roman Catholic (or, at least, Christian) religion and, apart from the Brazilians, the same language, which facilitates assimilation. Meanwhile both Brazilians and Romanians pick up the Spanish language quickly since they speak Romance languages descended from Vulgar Latin.

VOX’s anti-immigration policies, however, are gaining support among the unemployed and workers in general. The hard-right is their preferred party not the hard-left Sumar, according to the latest poll by the state-funded CIS (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Voter intention among those who consider themselves working class or poor (%)

| Political party | % |

|---|---|

| VOX | 24.6 |

| Socialists | 13.5 |

| Popular Party | 8.7 |

| Sumar | 4.7 |

While other EU leaders have tightened their borders against newcomers, Spain’s Prime Minister, Pedro Sánchez, is taking a pragmatic approach, championing migration and its economic benefits: ‘Immigration is not just a question of humanitarianism…, it’s also necessary for the prosperity of our economy and the sustainability of the welfare state’, he said. ‘The key is in managing it well’.

In May new regulations went into effect that eased migrants’ ability to obtain residency and work permits, and parliament began debating a bill to regularise undocumented migrants. The call was the result of a petition signed by 600,000 people and endorsed by 900 non-governmental organisations, business groups and the Roman Catholic Church.

The big rise in the foreign population is changing the population pyramid. Whilst only 56% of those born in Spain are aged between 20 and 64, almost 80% of immigrants are in that age bracket (see Figure 5). The working population needs to be rejuvenated, among other factors, in order to make the pay-as-you go pension system more sustainable.

Figure 5. Population by age group, those born in Spain and immigrants (% of total population)

| Age group | Born in Spain (%) | Immigrants (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 90 and over | 1.7 | 0.2 |

| 85-89 | 2.2 | 0.4 |

| 80-84 | 3.5 | 0.9 |

| 75-79 | 4.7 | 1.6 |

| 70-74 | 5.2 | 2.5 |

| 65-69 | 6.3 | 3.7 |

| 60-64 | 7.1 | 5.3 |

| 55-59 | 7.5 | 7.3 |

| 50-54 | 7.8 | 8.9 |

| 45-49 | 7.8 | 10.4 |

| 40-44 | 6.4 | 10.8 |

| 35-39 | 5.2 | 10.5 |

| 30-34 | 4.8 | 10.4 |

| 25-29 | 4.5 | 9.6 |

| 20-24 | 5.2 | 6.8 |

| 15-19 | 5.9 | 3.9 |

| 10-14 | 5.4 | 3.3 |

| 5-9 | 4.8 | 2.6 |

| 0-4 | 4.1 | 0.9 |

Another issue is to improve the education attainment of second-generation immigrants, one of the factors that affects their integration into the labour market. Only 39% of second-generation immigrants have basic education (compulsory secondary education ends at 16) and 25% a university degree, 24 percentage points below that of the native population.

On the other hand, a significant proportion of first-generation immigrants are overqualified for the job they get. This is largely due to the long time it takes for the homologation of their university degrees and professional qualifications, without which jobs in sectors such as health, education, the legal profession and engineering are impossible to obtain. There were close to 100,000 applications pending approval in June.

The Labour Ministry recently said the very large number of baby-boom-generation people (born between 1957 and 1977) retiring over the next 20 years will hit the labour market: 80% of ‘new’ jobs will be filling the posts vacated by those who retire. The situation of ageing workers is particularly acute in health (12.7% of workers are already 60 or over), public administrations (15.6%) and state education (7.8%). The total number of workers in these three sectors who are up for retirement in the coming years is more than 3.5 million.

The need for migrant workers, however, in a country with a major housing crisis has aggravated a problem which will take many years to resolve: the supply of properties cannot keep up with new arrivals, let alone with the resident population. The housing bottleneck raises questions over whether immigration can continue at its recent pace. Meanwhile Spain received 77,000 asylum seekers in the first half of 2025, most of them from Venezuela.

More than 8 million pupils were back at school this month after the summer holidays, 1.1 million of whom are foreign, 13.9% of the total and 30% more than five years ago. In seven of Spain’s 50 provinces, one in four students in state primary schools is foreign, giving teachers a complex challenge. The face of Spain is changing rapidly.