Theme

The following analysis presents some of the key outcomes of COP28. It discusses the negotiating positions of major emitters and the road ahead in globally-concerted climate action to treble renewables, double energy efficiency, ‘transition away from fossil fuels’ and finance the net-zero transition, a key topic ahead of COP29, which is to take place in Baku.

Summary

The largest gathering in the history of climate negotiations to date, the 28th Conference of the Parties (COP28), took place in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the seventh-largest oil producing country in the world, from 30 November to 13 December 2023. After a damning report on the progress made towards our collectively agreed climate goals since the Paris Agreement, and with political capital being allocated both to current conflicts and to the post-2020 recovery, COP28 was expected to be a challenging summit yielding limited results.

The key objectives of the COP included: concluding the first evaluation of our progress towards meeting the goals set in the Paris Agreement (the Global Stocktake, GST) through a COP decision; the establishment of the loss and damage fund that was agreed in Sharm-el-Sheik, Egypt, at COP27; advancing negotiations regarding the global goal on adaptation (GGA) and the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) on international climate finance (to be agreed upon in 2024); furthering the alignment of financial flows with climate goals; and finalising the rules governing international cooperation via market and non-market mechanisms under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

As the implementation of climate commitments advances, an increasingly sectoral approach is arguably emerging at international climate negotiations. At COP28 there were high hopes of including ambitious energy-related goals in the negotiating texts. The groundwork for including such goals in Dubai’s COP decisions was laid in April 2023 with the EU’s proposal at the Major Economies Forum and the Launch of the Global Renewables and Energy Efficiency Pledge at the World Climate Action Summit in Dubai. A pledge whose goal is to treble renewables (reaching 11TW of installed capacity) and double the global average annual rate of energy efficiency improvements (from 2% to 4%) by 2030. Biodiversity, water, food and heath, as well as the representation of youth in climate negotiations, were all expected to gain weight at COP28.

The UAE consensus, that encompasses the outcomes of COP28, established the long-awaited fund to address losses and damages. The GST decision called on Parties to treble renewables and double the rate of energy efficiency improvements by 2030. Most notably, the GST decision included the commitment to ‘transition away from fossil fuels’. COP28 also produced a framework for the GGA and worked towards the NCQG. Past hurdles in finalising the technical elements of market mechanisms were not overcome and negotiations will continue. The litmus test of the results of this COP will be both the extent to which the next round of climate commitments (Nationally Determined Contributions, NDCs) is aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement and the implementation of these commitments while ensuring sufficient climate finance is available for the transition, and, more broadly, that financial flows are aligned with climate goals.

Analysis

1. Introduction

Since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015, and alongside year-on-year record levels of greenhouse gas emissions –except for the pandemic–, the world has continued experiencing increasingly severe climate impacts. According to the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO, 2023), 2023 was the warmest year on record, with surface temperatures 1.4ºC (+/-0.12ºC) higher than those in the 1850-1900 period and ocean temperatures higher than those observed in the past 65 years. The year 2023 was also characterised by an onslaught of extreme weather events that led to growing concerns about food security and migration, a socially contingent and multi-causal event that may be exacerbated by climate change.

Despite the scientific consensus regarding the urgency of climate action,[1] the past year has, yet again, been marred by a myriad of challenges to enhance climate action amidst escalating geopolitical tensions and slow economic recovery vis-à-vis pre-pandemic levels (IMF, 2023). The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) synthesis report and the Emissions Gap Report (UNEP, 2023) reiterated that climate action is woefully insufficient to meet our climate goals and that there is limited time for course correction if we are to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. Globally, Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) estimates that Paris-aligned global annual climate finance needs could reach US$9 trillion[2] by 2030 in their average scenario (with a range between US$5.9 to US$12 trillion) and US$10 trillion from 2031 to 2050 in the average scenario (with a range between US$9.4 trillion to US$12.2 trillion), up from US$1.3 trillion in 2021/2022. The above context adds to the inherent complexity of international climate negotiations.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The second section analyses the outcomes of the global stocktake. The third discusses the significant advances in setting up the Santiago Network and the loss and damage fund. The fourth section delves into the framework for the global goal on adaptation and the pending work on adaptation indicators. The fifth section reflects on the limited advances in international climate finance and the underlying lack of trust between developed and developing countries. The sixth section reviews the stalemate in international cooperation mechanisms under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. Advances in water are presented in section seven. Additional and emerging topics under discussion at COP28 are highlighted in section 8, which also discusses some of the initiatives presented within the Global Climate Action Agenda (GCAA). Section 9 summarises some of the dialogues and work programmes that will take place ahead of COP29. The last section presents the key conclusions.

2. Global stocktake: transitioning away from fossil fuels

According to Article 14 of the Paris Agreement and Decision 19/CMA.1, Parties are required to evaluate their progress towards the objectives outlined in Article 2 as regards mitigation, adaptation and means of implementation (MoI),[3] periodically and collectively, starting in 2023 and every five years thereafter.

The first GST was anticipated to conclude during COP28 with either a decision and/or a political statement. The GST text was indeed agreed on 13 December[4] and included several key levers for achieving the net-zero goal, although the language used was overall relatively weak, as expected. Novel elements included a call for Parties to contribute to the goal of trebling renewables and doubling the rate of energy efficiency improvements by 2030.[5] The GST also calls on Parties to engage in economy-wide emission reductions. It includes a sectoral reference to the need to decarbonise transport. Most notably, the GST sends an unequivocal signal to ‘transition away’ from fossil fuels, accelerating efforts to do so this decade, with the goal of having a predominantly fossil-free energy system by mid-century in alignment with science and in an orderly and equitable manner while recognising the need to reach a peak in emissions by 2025. Stronger language on the ‘phase-out’ of all fossil fuels would not have been accepted by the African Group of Negotiators, the Arab Group, Australia and the G77+China, among others, in spite of support for the full phase-out language supported by the High Ambition Coalition. The agreement also reiterated the call from Sharm el-Sheikh to eliminate ‘inefficient’ fossil fuel subsidies that do not address energy poverty or just transitions, with no set date for this to occur.

However, paragraph 28 of the GST decision, reproduced below in Box 1, includes significant flexibility and nuances, with some observers claiming that the agreed text is not really a breakthrough in signalling the way forward towards ‘transitioning away from fossil fuels’ but rather a negotiation exercise to present pre-existing transitioning trends that are already embedded in the strategic plans and vision of key emitters, including the UAE. The role of transitional fuels in Paragraph 29 is underspecified and not directly linked, for instance, to the updated net-zero pathways presented by the International Energy Agency (IEA, 2023) that state that beyond projects planned as of 2021, no new oil and gas fields, as well as no new coal mines, mine expansions nor unabated coal plants should be approved for development.[6]

Box 1. Paragraph 28 of the Outcome of the Global Stocktake

| 28. Further recognises the need for deep, rapid and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in line with 1.5ºC pathways and calls on Parties to contribute to the following global efforts, in a nationally determined manner, taking into account the Paris Agreement and their different national circumstances, pathways and approaches: (a) Trebling renewable energy capacity globally and doubling the global average annual rate of energy efficiency improvements by 2030. (b) Accelerating efforts towards the phase-down of unabated coal power. (c) Accelerating efforts globally towards net-zero emission energy systems, utilising zero- and low-carbon fuels well before or by around mid-century. (d) Transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science. (e) Accelerating zero- and low-emission technologies, including, inter alia, renewables, nuclear, abatement and removal technologies such as carbon capture and utilisation and storage, particularly in hard-to-abate sectors, and low-carbon hydrogen production. (f) Accelerating and substantially reducing non-carbon-dioxide emissions globally, including in particular methane emissions by 2030. (g) Accelerating the reduction of emissions from road transport on a range of pathways, including through development of infrastructure and rapid deployment of zero- and low-emission vehicles. (h) Phasing out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that do not address energy poverty or just transitions, as soon as possible. |

The GST also calls for strengthened 2030 NDCs. In the short-term, Parties are encouraged to propose ambitious, comprehensive emission reduction targets spanning all GHG emissions, sectors and categories. These targets should be aligned with the 1.5ºC limit and incorporated by early 2025 into the forthcoming round of NDCs that should be informed by GST conclusions. In the upcoming round of NDCs both developed and developing countries will have to include emission reduction efforts for all greenhouse gases.

3. Loss and damage: fund established, replenishment and governance pending plus a fully operational Santiago Network[7]

Residual climate risks of experiencing losses and damages are those that persist –even after ambitious mitigation and adaptation efforts (IPCC, 2022, 2023)–. These risks result in both economic and non-economic losses and damages. Building on Article 8 of the Paris Agreement, COP27 witnessed a historic agreement to establish a fund to compensate for losses and damages resulting from both insufficient mitigation and the limits to adaptation. The establishment of the fund to address losses and damages has been eagerly awaited for three decades by the most vulnerable countries that have contributed the least to climate change. To operationalise this fund at COP28, a ‘transitional committee’ was established in 2023, holding five meetings throughout the year. Discussions focused on the structure, governance, contributions, access to funds, and the collection of information and experiences. Some of the most controversial elements for the establishment of the fund included: (1) the location of the fund; (2) its contributors and the recipients of funding; (3) its governance; (4) the inclusion of civil society; (5) access to the fund by local entities; (6) the integration of the fund into the international climate finance architecture; (7) the type of funding; and (8) the sources of funding.

In an unprecedented diplomatic move, the opening session at COP28 delivered a historic agreement on the establishment of the loss and damage fund, with a carefully orchestrated initial capitalisation of US$792 million. The EU and its Member States pledged over half of the funds (US$410 million), with Germany pledging US$100 million and Spain €20 million. Other notable pledges include those of the UAE (US$100 million), the UK (US$50 million) and the US (US$17 million). However, this falls far short of the annual losses and damages estimated at US$525 billion (US$26,25 billion annually on average) in the past two decades endured by the most vulnerable countries to climate change. Unresolved issues regarding the fund include how to scale up the funds to meet the needs of the most vulnerable countries, and the long-term replenishment of the fund, with proposals made at COP28 to establish taxation on aviation to this end.

The operationalisation of the loss and damage fund could have been a roadblock for COP28. However, the UAE Presidency managed to broker a deal on day one, even if developing countries had to accept the fund being temporarily hosted by the World Bank, albeit as an independent entity under the UNFCC that, according to developed countries, would help speed up the operationalisation of the fund. Still to be decided is the permanent host of the loss and damage fund.

On the governance of the fund, Parties agreed that it would have a 26-person board, with a majority of members selected from developing countries. The board will name the fund, a controversial aspect for the US, that referred to it as the ‘climate impacts response fund’ and emphasised the fact that funding was to be voluntary, clearly indicating the US concern about potential liability claims derived from losses and damages that could be attributed to its historical and current emissions.

In addition to the establishment of the loss and damage fund, and five years after its announcement at COP25 in Madrid, the Santiago Network –which is intended to provide technical assistance for vulnerable developing countries experiencing loss and damages– became fully operational at COP28. The UNFCCC secretariat will additionally develop a loss and damage synthesis report on a regular basis. A consortium between the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) and the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) was chosen at this COP to host its secretariat for the next five years.

4. Adaptation framework established: goals, indicators and funding pending

Historically, climate change negotiations focused predominantly on mitigation. More recently, the UNFCCC has gradually increased its efforts on adaptation. According to Article 2.1(b) of the Paris Agreement, there is a need to enhance adaptive capacity and resilience. Additionally, Article 7.1 states that Parties shall establish a global goal on adaptation (GGA) aimed at reducing vulnerability.

Since 2015 there has been increasing pressure to further define the GGA but it garnered limited attention at UN negotiations until 2021. During COP26, held in Glasgow, the operationalisation of the GGA advanced through the establishment of the two-year Glasgow-Sharm el-Sheikh Work Programme (GlaSS). The programme aimed to provide a deeper understanding of the GGA while increasing visibility on major issues and opportunities related to climate adaptation. In the meetings of the GlaSS, developing countries supported a more specific definition of the elements of the GGA compared with developed countries. Consequently, at the suggestion of G77+China, there was a call for GlaSS to result in a GGA framework to be adopted at COP28, which was unlikely to be highly specific due to the different views among Parties on the matter.

The adoption of a GGA framework at COP28 was to enhance national, local and transboundary adaptation efforts by improving planning and advancing on implementation. Moreover, it was expected to provide means for evaluating the collective progress on adaption and support. The Paris Agreement, however, does not describe a quantitative goal for adaptation but establishes the GGA as a shared aspirational goal. The most pressing and complex challenges regarding the establishment of the GGA include defining globally relevant targets and metrics to assess progress, as well as defining a clear roadmap for implementation towards the second GST.

In line with limited advances in the past, the results of adaptation negotiations have been underwhelming at COP28. The need for transformative adaptation and resilience is increasingly urgent, whereas current adaptation tends to be gradual and piecemeal. Indicators, monitoring systems and strong commitments are lacking, with 60% of countries that have National Adaptation Plans not conducting evaluations of their implementation as of 2021. Within the GGA text approved, the following key elements can be highlighted:

- The purpose of the framework for the GGA (called the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience, UAE FGCR) is to guide the achievement of the GGA and to help review the progress made to reduce the impacts, risks and vulnerabilities associated with climate change, as well as to enhance action and support for adaptation. Informally, this is referred to as the guiding star.

- The GGA incorporates both transformative and incremental adaptation approaches, taking into account scientific evidence and local and Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge.

- In the adaptation decision, seven sectoral priorities are identified (see Box 2 below) but quantitative objectives were not established. COP28 called on Parties to reduce climate impacts and enhance resilience in water, food, health, ecosystems, infrastructure, poverty eradication and cultural heritage.

- Furthermore, objectives of a more operational nature were requested. For instance, setting objectives by 2030 associated with the different stages of the adaptation policy cycle: all Parties must have adaptation plans informed by impacts, vulnerability and risk analyses; and all Parties will have National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) and will have made substantial progress in their implementation, as well as in developing a monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) system. Additionally, by 2027, Parties were mandated to have early warning systems, climate information systems, and observation capacity.

- The abovementioned objectives are implemented by countries voluntarily and in accordance with national circumstances.

- The adaptation framework recognises the important role of non-Party stakeholders[8] in achieving the GGA.

- The adaptation framework also recognises the importance of Means of Implementation (MoI). Regarding adaptation finance, the framework expresses concern about the adaptation funding deficit and urges developed countries to, at least, double their collective provision of climate finance for adaptation to developing countries.

- Furthermore, future GSTs will incorporate information on the degree of compliance with adaptation goals, supported by a synthesis report conducted by the UNFCCC Secretariat on a regular basis.

Box 2. The GGA decision

| The GGA identifies seven sectoral priorities summarised in the following objectives for 2030. According to Article 9, these priorities are: Significantly reducing climate-induced water scarcity. Enhancing resilience to water-related hazards. Foster a climate-resilient water supply and climate-resilient sanitation. Enable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all.Attaining climate-resilient food and agricultural production, supply and distribution of food, as well as increasing sustainable and regenerative production and equitable access to adequate food and nutrition for all.Attaining resilience against climate change-related health impacts, promoting climate-resilient health services, and significantly reducing climate-related morbidity and mortality, particularly in the most vulnerable communities.Reducing climate impacts on ecosystems and biodiversity, and accelerating the use of ecosystem-based adaptation and nature-based solutions, including through their management, enhancement, restoration and conservation and the protection of terrestrial inland water, mountain, marine and coastal ecosystems.Increasing the resilience of infrastructure and human settlements to climate change impacts to ensure basic and continuous essential services for all, and minimising climate-related impacts on infrastructure and human settlements.Substantially reducing the adverse effects of climate change on poverty eradication and livelihoods, in particular by promoting the use of adaptive social protection measures for all.Protecting cultural heritage from the impacts of climate-related risks by developing adaptive strategies for preserving cultural practices and heritage sites and by designing climate-resilient infrastructure, guided by traditional knowledge, Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge and local knowledge systems. |

African and Latin American countries were particularly disappointed with the result on adaptation. They were expecting more details on finance, targets and technology transfer but the language used during the negotiations of the GGA was very weak, lacking the required detail to allow adequate monitoring. Transboundary climate impacts will also be further discussed in COP29. There is no agenda item to continue talking about adaptation, but there is a two-year work programme (named the UAE-Belém work programme) that will help define adaptation indicators. The UNFCCC secretariat will produce a synthesis report on adaptation, similar to the reports currently published on Nationally Determined Contributions and Long-Term Strategies.

5. International climate finance

According to the UEA Presidency, COP28 managed to mobilise US$85 billion in climate finance, including US$3.5 billion pledged for the Green Climate Fund. Additionally, ALTÉRRA, a private investment vehicle chaired by the COP President, Sultan Al Jaber, was presented at COP aiming to mobilise US$250 billion and paying special attention to emerging economies and developing countries which have greater difficulties in accessing climate finance.

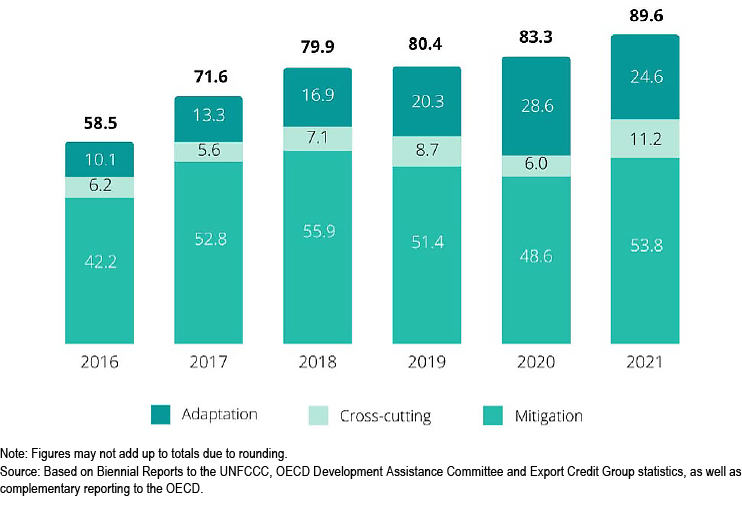

As for international climate finance committed in the Paris Agreement, in 2023 the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) indicated that the target of mobilising US$100 billion annually for developing countries from 2020 onwards was likely to have been achieved in 2022, with a two-year delay. The achievement of the US$100 billion goal was disputed by Oxfam, that stated that only a quarter of public climate finance has been disbursed as grants, exacerbating the debt burden of developing countries. Whereas the fulfilment of the international climate finance commitment will be welcomed, if and when it is confirmed –see Figure 1 for data from 2016 to 2021–, the delay has eroded trust between developed and developing countries and prevented enhanced ambition.

Figure 1. Climate finance provided and mobilised in 2016-21 (US$ bn)

Source: OECD (2023).

Furthermore, the delay in disbursing climate finance to developing countries complicates negotiations for establishing a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) in 2024, which would be applicable from 2025 onwards. Although the establishment of the NCQG is not expected until COP29, progress in the negotiations was anticipated at COP28, which resulted in a decision to organise a high-level ministerial dialogue and technical dialogues during 2024.

Gaining trust among Parties will also depend on whether the updated international climate finance commitment responds to the needs of recipient countries. To meet those needs, the NCQG would need to move beyond the current US$100 billion commitment to a significantly higher amount, potentially multiplying the current figure by six. Such scaling up would require, according to developed countries, expanding the donor base to large emitters like China and the Gulf states. However, there has been some resistance from developing countries to expanding the donor base as they perceive it as an attempt to shift the responsibility of providing climate finance away from developed countries. At COP28 the final text on long-term climate finance urges developed countries to deliver on the US$100 billion per year goal ‘urgently and through to 2025’. During COP28, discussions emerged about the need to mobilise climate funds from other sources including taxing the aviation and maritime sectors.

The GST decision underscored the urgency of mobilising innovative sources of funds by ‘call[ing] on Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and other financial institutions to further scale up investments in climate action’, also emphasising the role of ‘governments, central banks, commercial banks, institutional investors and other financial’ organisations in ‘ensuring or enhancing’ access to this finance.

Supporting further involvement of international financial institutions in global climate finance, the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance presented a report during COP28, highlighting the need to reform the global financial architecture by 2030, actively involving key stakeholders –countries, the private sector, the MDBs, donors and private philanthropy–. Some ideas proposed on the report were repeated at the UAE Leaders’ Declaration on a Global Climate Finance Framework, including widening the sources of concessional finance, exploring emissions pricing and taxation mechanisms, and strengthening MDBs. This was seen as an attempt to consolidate several initiatives aimed at catalysing comprehensive financial reform –eg, Barbados’ Bridgetown Initiative, the Summit on a New Global Financing Pact and the Nairobi Declaration from the inaugural African Climate Summit–.

Adaptation finance was also discussed at COP28 in line with the goal of doubling 2019 figures by 2025. Beyond the agreed doubling commitment, the need for significantly scaled up adaptation finance was acknowledged. The 2023 edition of the UNEP Adaptation Gap Report estimated that the adaptation finance gap ranges between US$194 and US$366 billion (note that according to the OECD report, adaptation finance amounted to US$24.6 billion in 2021). At COP29 a ministerial dialogue is expected on adaptation finance.

The need to make all finance flows consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement, as laid out in its Article 2.1(c) was reiterated during COP28. The 2023 technical dialogue on the alignment of financial flows and climate goals will continue in 2024. Climate finance is anticipated to be one of the biggest agenda items in 2024 (alongside just transition) given the significant needs of developing countries in order to implement their NDCs. These needs are estimated at US$5.8-US$5.9 trillion by 2030 according to the first report on the determination of the needs of developing country Parties.

6. Carbon markets and voluntary cooperation

In the Paris Agreement it is Article 6 that governs and establishes the rules for international cooperation through market mechanisms and non-market based approaches. Four-fifths of countries have stated their willingness to use market mechanisms to meet their NDCs. COP28 was set to continue negotiating several technical elements related to Article 6 that had remained unresolved from previous years. Despite these ongoing negotiations, the conference did not adopt a decision on several pending issues.

More specifically, COP28 did not reach a consensus decision on Article 6.2[9] due to disagreements regarding the process and controls, with the US advocating looser standards and the EU and AILAC[10] supporting more stringent supervision. Moreover, discussions on authorisation processes, including the potential revoking of authorisations after the transfer of Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs) raised concerns about the risk of double-counting emission reductions.[11] COP28 aimed to provide clarity on several technical elements, including: (1) an electronic reporting format –with the adoption of standardised reporting tables on cooperative approaches expected for November 2024–; (2) the interconnection between national registries under 6.2 and the registry mechanism under 6.4; and (3) guidance on applying cooperative approaches across NDCs to prevent double-counting. The Bonn Intersessional meeting in 2024 will continue working on addressing key items such as guidelines on the designation of information as ‘confidential’.

Countries also failed to reach an agreement on Article 6.4[12] of the Paris Agreement, which means that negotiations will continue. Recommendations for guidance on methodologies and GHG removals under the Article 6.4 mechanism were considered at COP28 but no formal decision was adopted. Discussions about the principles shaping the assessment methodologies, such as baselines and additionality tests, were also fraught with difficulties.

The COP presidency agreed the implementation details of the Article 6.8 work programme taking place from the end of COP28 through to the Bonn meetings in June 2024 and a web-based platform for sharing information on Non-Market Approaches (NMAs) is expected to be established.

7. Water resilience

Water plays a pivotal role in adapting to climate change. Since the year 2000, water-related hazards have accounted for nearly three-quarters of all natural disasters worldwide. As climate change increasingly disrupts precipitation patterns globally, the IPCC estimates that a 2ºC warming could expose up to 3 billion people to growing water scarcity. However, it was not until COP27 that international climate negotiators included water in decision texts, urging countries to incorporate water into their climate adaptation initiatives.

The COP28 presidency was set to increase the relevance of water in the climate agenda by prioritising three key areas: food systems that are resilient, the conservation and restoration of freshwater ecosystems, and urban water resilience. This commitment was reflected in the dedication of a full conference day to in-depth discussions on food, water and agriculture, featuring a high-level ministerial dialogue. Additionally, the UAE had formed a partnership with the Netherlands and Tajikistan, the co-hosts of the UN 2023 Water Conference, who served as COP28 Water Champions.

The Food, Agriculture and Water Day at COP28 witnessed numerous policy engagements to bolster water security. For instance, during the ministerial dialogue on building water-resilient food systems, the UAE and Brazil initiated a two-year partnership to help Parties to integrate water and food considerations into their national climate strategies. Additionally, more than 30 new countries joined the Freshwater Challenge, an initiative launched at the 2023 UN Water Conference to restore 300,000 kilometres of rivers and 350 million hectares of wetlands by 2030.

By the end of COP28, 159 countries, covering nearly 80% of the world, had endorsed the UAE Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems and Climate Action, committing to integrate food and food systems into their NDCs by 2025 with a pledge to showcase tangible progress at COP29 and COP30. Signatories include major emitters and global players in the food system, such as Argentina, Brazil, China, the EU, Russia, Turkey, Ukraine and the US. Furthermore, the International Drought Resilience Alliance (IDRA), introduced at COP27 under the leadership of Spain and Senegal, expanded during COP28, indicating a shared commitment to strengthen global readiness to address severe droughts.

8. Health, Biodiversity, Agriculture, Food, Youth, Gender and the Global Climate Action Agenda at COP28

The COP28 was anticipated to showcase numerous additional initiatives. Notably, the health-climate nexus was expected to gain prominence with the COP28 Declaration on Climate and Health, developed alongside the World Health Organisation (WHO). Additionally, the agenda on food systems and agriculture was also presented at COP28 given the sector’s contribution to global emissions (estimated to amount to just under a third[13] of anthropogenic emissions by FAO), the scope for mitigation and adaptation needs of food systems.

The rapprochement of the biodiversity and climate change agendas was significant throughout the two weeks of negotiations, in alignment with the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). In a first-of-its kind initiative, UNFCCC COP28 President and the President of the COP15 Convention on Biological Diversity released a Joint Statement on Climate, Nature and People, which recognises that urgent action is required to deliver both the goals of the Paris Agreement and those of the GBF. This statement solidifies the commitment through shared objectives, including aligning NDCs, NAPs and National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs)[14] towards COP30 and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) COP16. The joint statement advocates a comprehensive, whole-of-society approach to the planning and execution of climate, biodiversity and land management initiatives. Simultaneously, it promotes coherence and interoperability in data collection, methods and reporting frameworks across sectors within the scope of these initiatives.

Two additional important topics at the Summit were youth and gender. COP28 featured the largest initiative to date to involve youth in the UNFCCC process. Inspired by the COP27 Youth Envoy role, COP28 established the role of the Youth Climate Champion (YCC) and featured the official launch of Youth Stocktake –the first comprehensive analysis of youth engagement in the UNFCCC process–. It also introduced the COP28 Youth Climate Delegates Programme to expand youth participation and representation. There will also be an expert dialogue to explore both the impacts of climate change on young people as well as how to address them. As for gender the Gender Action Plan (GAP) will be reviewed in 2024, focusing on the progress, challenges, gaps, and priorities in implementing the plan.

Continued engagement between Parties and non-Party stakeholders is key to delivering on the 1.5ºC goal, although data collection and monitoring regarding voluntary commitments are to be fully developed if greenwashing is to be avoided. Once again, COP28 yielded numerous sectorial pledges and declarations. Some of these initiatives under the Global Action Agenda (GCA) are summarised in Figure 2 below.

Figure 1. Summary of GCA at COP28

| Pillar | Initiative | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1) Fast-tracking a just, orderly and equitable energy transition | Global Renewables and Energy Efficiency Pledge | Signatories strive to treble renewables (to 11 TW) and double the rate of energy efficiency improvements (from 2% to 4%) by 2030. |

| Global Cooling Pledge | Signatories seek to reduce cooling-related emissions across all sectors by at least 68% globally by 2050, compared with 2022 levels. | |

| Oil and Gas Decarbonisation Charter | Signatories commit to align around net-zero by 2050, zero routine flaring by 2030 and near-zero methane emissions. Today, 50 companies (accounting for more than 40% of global oil production) have signed on to the Charter. | |

| Declaration to Triple Nuclear Energy | Signatories work to triple nuclear energy capacity globally by 2050, inviting shareholders of international financial institutions to encourage the adoption of lending policies that support nuclear energy. | |

| 2) Fixing climate finance | Declaration on a Global Climate Finance Framework | Signatories aim to unlock the investment potential of climate finance by engaging in joint efforts, ensuring inclusivity, and delivering at scale. |

| Joint Declaration and Task Force on Credit Enhancement of Sustainability-Linked Sovereign Financing for Nature and Climate | Multilateral development banks and international organisations have signed it and launched a global ‘task force’ to respond to the needs of developing countries to address climate, nature and debt challenges. | |

| 3) Focusing on people, lives, and livelihoods | COP28 UAE Declaration on Climate and Health | Signatories work towards climate resilience addressing its interaction with health systems. |

| UAE Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems and Climate Action | Signatories increase efforts to boost resilience and adaptation to reduce vulnerability for farmers and food producers; therefore, improving food security. Non-Party stakeholders brought more than 200 organisations that signed the Call to Action for Transforming Food Systems for People, Nature and Climate. | |

| 4) Full inclusivity | Youth Climate Champion and the outcome of the Youth Stocktake | The Presidency formalised the position of the Youth Climate Champion, ensuring the engagement of youth and other marginalised groups in the UNFCCC process. Moreover, COP28 and YOUNGO –the global network of youth climate activists– introduced the Youth Stocktake, a thorough examination of youth participation in climate diplomacy. |

| COP28 Gender-Responsive Just Transitions and Climate Action Partnership | Signatories promote just and gender-inclusive transitions and align with the objectives of the enhanced Lima Work Programme on Gender, including its Action Plan. They commit to reconvene during COP32 for a dialogue aimed at sharing progress. |

9. Looking ahead

Many pending issues remain unresolved ahead of the COP29 in Azerbaijan. Some of the key initiatives, dialogues and advances under existing work programmes expected in 2024 and beyond are listed below:

- The first annual GST dialogue will be convened at the next UNFCCC meeting in June 2024. Countries will share their experience on using the GST outcome to inform their upcoming NDCs.

- The decision on the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience (otherwise known as the framework for the global goal on adaptation) includes a two-year programme (known as the UAE-Belém work programme) to further strengthen the adaptation indicators.

- The Just Transition Work Programme. At least two dialogues are to be convened before COP29. Mitigation, adaptation and workers’ rights were included in the programme (the latter at the request of the EU).

- The Mitigation Work Programme will hold two global dialogues in 2024.

- The Presidencies of COP28 and COP29 will appoint the first official Youth Climate Champions.

- A high-level ministerial dialogue and technical dialogues will take place during 2024 for the NCQG.

- The technical dialogue on the alignment of financial flows and climate goals will continue in 2024.

Conclusions

The road to COP29 and beyond

COP28, the largest international climate gathering to date, adopted the fund to address losses and damages during its opening plenary. It was the first time in the history of climate negotiations that one of the big agenda items was agreed at the outset of a Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC. A diplomatic move that helped drive the negotiations forward at the outset in Dubai. COP28 also concluded the first Global Stocktake delivering its COP decision. A decision that welcomed the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report restating the need to reduce emissions by 43% by 2030 versus 2019 levels and peak global emissions ahead of 2025. Most relevant in the GST decision is the call to treble renewables and double the rate of energy efficiency improvements. Despite the EU’s best efforts to include ‘phase out’ language regarding ‘unabated’ fossil fuels, Parties settled for more flexible language to ‘transition away’ from fossil fuels, which was nevertheless hailed as breakthrough and as a clear signal of the commitment to a decarbonised development model that will help guide governments, boardrooms and banks. Stronger language on non-CO2 gases was also included in the text, as was the previous (COP27) call to eliminate ‘inefficient’ fossil fuel subsidies that do not address energy poverty or support a just transition.

Another relevant outcome of COP28 was the adoption of a framework for the global goal on adaptation (named the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience) –pending future work on indicators–. The technical details to ensure environmental integrity regarding international cooperation through the use of market mechanisms were once again a gordian knot in negotiations and hence were deferred to future climate talks. International climate finance disbursed, the need to enhance the US$100 billion commitment and, more broadly, the goal of aligning financial flows with climate goals were discussed but were not expected to be resolved during COP28. Additional topics that emerged in Dubai, which will be further discussed in all likelihood in future COPs, include water, biodiversity, ecosystems, nature and food systems, among others.

Non-Party stakeholders continue to be actively engaged in global climate action, as seen in the 2023 the Yearbook of Global Climate Action. Numerous initiatives on decarbonisation, climate finance, health, food security, gender equality and youth emerged from COP28 and will have to be monitored to prevent a ‘green mirage’ of ambitious voluntary climate commitments that do not materialise.

In 2024, the OECD is set to provide additional information of the extent to which the US$100 billion international climate finance commitment was met in 2022. A new international climate finance goal (the NCQG) is due in 2024. Information on the commitment to meet the doubling of 2019 adaptation finance by 2025 is also expected in Baku, alongside further discussions on the alignment of financial flows with climate goals. Additionally, rethinking the global finance architecture, improving the assessment and management of climate-related financial risks and how to tap into innovative financing sources are unresolved issues deferred to COP29 in Baku.

Progress at COP28 will be gauged by the next round of NDCs expected between the end of 2024 (when COP29 in Azerbaijan will take place) and 2025, ahead of COP30 in Brazil. This round of NDCs will be showcased at a dedicated event organised by the United Nations Secretary General, providing Parties with an opportunity to highlight their climate leadership. Ultimately, the success of these pledges will be determined by whether countries follow through with substantial policy reforms and action at the national level while also ensuring the availability of financial resources for their implementation.

[1] See the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s sixth Assessment Report (AR6), which was welcomed by the Parties at COP28.

[2] Note that throughout the text US$1 trillion = 1012 and US$1 billion = 109.

[3] Means of Implementation refer to financial, technical, and capacity-building support.

[4] As part of the set of agreements reached in Dubai known as the UAE consensus.

[5] A call spearheaded by the EU and Spain holding the rotating Presidency of the Council of the EU.

[6] The IEA 2023 update of its Net-Zero roadmap nevertheless highlights the need for investments in existing oil and gas assets and approved developments as well as the need to sequence fossil fuel phase-out with renewable phase-in to limit price spikes while ensuring access to energy.

[7] The Santiago Network seeks to ‘connect vulnerable developing countries with providers of technical assistance, knowledge, and resources’ to enable vulnerable countries to address losses and damages.

[8] Non-state actors include civil society organisations (CSOs), subnational governments, the private sector, etc.

[9] Article 6. 2 allows bilateral and multilateral trading of emission reductions or removals (called Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes) by countries. There is no UN supervision for Article 6.2 credits. It will be up to countries to define environmental integrity, baselines and additionality for Article 6.2 credits. Countries are also allowed to classify bilateral trades as confidential, limiting transparency and oversight.

[10] Note that the Independent Association of Latin America and the Caribbean (AILAC) is ‘a group of eight countries that share interests and positions on climate change’: Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala (its current chair), Honduras, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Chile.

[11] This can occur if the same emissions reduction is counted by both the buyer and the seller.

[12] Article 6.4 is expected to deliver a global carbon market supervised by the UN. The market will work as follows: developers will request their projects be registered by the UN Supervisory Body. The country where the project is implemented, and the Supervisory Body, will approve the project. Then UN-backed carbon credits (known as A6.4 ERs) will be issued and the credits can then be acquired by Parties, companies and individuals.

[13] Emissions included from the following sectors: farming, land use, crops and livestock, household food consumption and waste, and energy used in farm and food processing and transport.

[14] Instruments for translating the CBD into national action.