Spain’s fourth general election in as many years, a record for an EU country, failed to unblock the political impasse and produced a surge in support for the far-right nationalist VOX which more than doubled its previous number of seats.

But as after April’s election, neither the three main parties in the left wing bloc nor the same number on the right have an absolute majority of seats (176). They will have to be more flexible in striking a deal that enables a government of whatever colour to be formed, or yet another election will have to be called. Along with Malta, Spain is the only EU country not to have had a coalition government in the last 40 years.

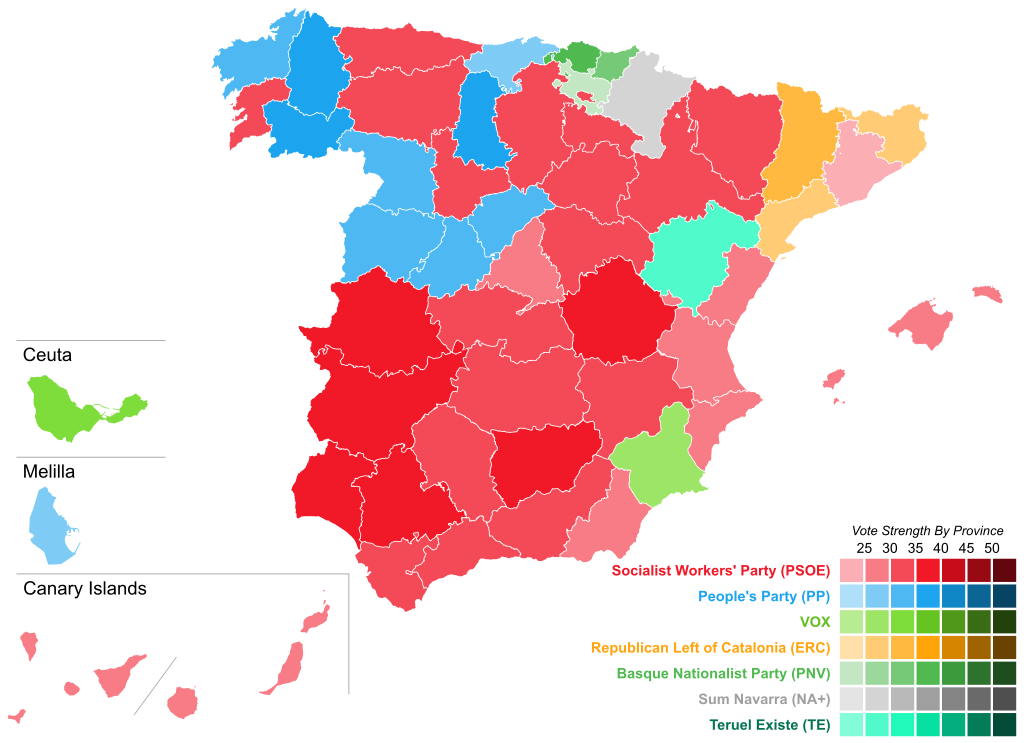

The Socialists again won the most seats (120 in the 350-seat Congress, down three and 800,000 fewer votes), while the Popular Party increased its number by 22 to 88 and VOX, the biggest winner, from 24 to 52 (+one million votes), making it the third largest party (see Figure 1). Ciudadanos (Cs) paid a heavy price for its rightward lurch, plummeting from 57 to just 10 seats. Its leader Albert Rivera, who set his sights on overtaking the PP (Cs only won nine fewer seats and 200,000 fewer votes in April’s election) in a disastrous strategy for a party that promoted itself as centrist and liberal, resigned. Más País, a split from Unidas Podemos, won three seats. Voter turnout was 69.9% compared to 75.7% in April. A lower turnout tends to benefit the right.

Figure 1. Results of general elections, November 2019 and April 2019 (seats, millions of votes and % of total votes)

| November 2019 | April 2019 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seats | Votes | % | Seats | Votes | % | |

| Socialists | 120 | 6.75 | 28.0 | 123 | 7.48 | 28.7 |

| Popular Party | 88 | 5.01 | 20.8 | 66 | 4.35 | 16.7 |

| VOX | 52 | 3.64 | 15.1 | 24 | 2.67 | 10.3 |

| Unidas Podemos | 35 | 3.09 | 12.8 | 42 | 3.73 | 14.3 |

| Catalan Republican Left | 13 | 0.86 | 3.6 | 15 | 1.01 | 3.4 |

| Ciudadanos | 10 | 1.6 | 6.8 | 57 | 4.13 | 15.9 |

| J×Cat | 8 | 0.52 | 2.2 | 7 | 0.49 | 1.9 |

| Basque Nationalist Party | 7 | 0.37 | 1.6 | 6 | 0.39 | 1.5 |

| EH Bildu | 5 | 0.27 | 1.1 | 4 | 0.25 | 1.0 |

| Más País | 3 | 0.50 | 2.1 | – | – | – |

| CUP | 2 | 0.24 | 1.0 | – | – | – |

| Canarian Coalition | 2 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.13 | 0.5 |

| Other parties | 5 | 0.30 | 0.9 | – | – | – |

| Vote turnout (%) | 69.9 | 75.75 | ||||

Source: Spanish Ministry of Interior.

Spain now has a far-right party in national political life on a par with that in other EU countries. It is no longer an exception. VOX obtained 15.1% of the vote compared to the 12% of Germany’s AfD in the 2017 general election, 13% for France’s National Front that same year, 17% for Italy’s La Liga in 2018 and 16% for Austria’s Freedom Party last September.

Emboldened by the Socialists’ better results in May’s local and European elections, Pedro Sánchez, the acting Prime Minister, took a gamble and returned to the polls on 10 November after botched negotiations to form a coalition with the radical-left Unidas Podemos which, together with the support of smaller parties, would have produced a government, albeit a tenuous one. He thought he stood a good chance of winning more seats.

Broadly speaking, Ciudadanos lost votes to the PP, while VOX attracted a large number of young and disaffected voters. The PP’s leader Pablo Casado moved somewhat back to the centre, enabling him to recover 650,000 votes.

As well as the ideological divide between the left and the right, there was the burning issue in the electoral campaign of the push for independence in Catalonia, nine of whose leaders were sentenced last month to up to 13 years in prison for sedition for organizing an unconstitutional referendum on secession and a unilateral declaration of independence. Those sentences sparked violent protests in which some 600 people were injured and €10 million of damage done.

Santiago Abascal, VOX’s leader, played the anti-Catalan card hard and it resonated among a large swathe of conservatives angry at appeasement of Catalan nationalism by both the PP and the Socialists since Spain returned to democracy 40 years ago. Abascal called for the banning of separatist parties as ‘criminal organizations’ and a state of emergency to be imposed in Catalonia, following the protests.

The three Catalan parties in the national parliament are all pro-independence and between them have 23 seats, two more than in April as the anti-capitalist Popular Unity Candidacy (CUP) entered for the first time. It goes without saying they will not support a Socialist government, and if they did this would be like a red rag to a bull and probably boost support for VOX.

Spain’s parliament is now even more fragmented: 16 parties have seats in it, up from 13 after April’s election. This fragmentation began as of 2015 when the combined share of votes of the Socialists and the PP, the two parties that have dominated politics, dropped to 51% from a peak of 84% in 2008 as a result of the emergence of new parties in response to the economic crisis and the Catalan issue (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Results of General Elections, 2015 -2019 (Seats and % of total votes)

| December 2015 | June 2016 | April 2019 | November 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Popular Party | 123 (28.7) | 137 (33.0) | 66 (16.7) | 88 (20.8) |

| Socialists | 90 (22.0) | 85 (22.7) | 123 (28.7) | 120 (28.0) |

| Unidas Podemos1 | 69 (20.6) | 71 (21.1) | 42 (14.3) | 35 (12.8) |

| Ciudadanos | 40 (13.9) | 32 (13.0) | 57 (15.8) | 10 (6.8) |

| Catalan parties2 | 17 (4.6) | 17 (4.6) | 22 (5.8) | 23 (6.0) |

| Basque parties3 | 8 (2.0) | 7 (2.0) | 10 (2.5) | 12 (2.7) |

| VOX | – | – | 24 (10.3) | 52 (15.1) |

| Other parties | 1 (4.6) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (3.6) | 5 (0.9) |

(1) Unidas Podemos as of 2016 election when joined forces with United Left and includes regional offshoots.

(2) Junts per Catalunya, CDC and PDeCAT, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya and CUP.

(3) Basque Nationalist Party and EH Bildu.

Source: Spanish Ministry of Interior.

There are several scenarios for forming a new government. The best but unlikely one would be a German-style ‘grand coalition’ between the Socialists and the PP, with 208 seats (see Figure 3). An historic opportunity was wasted after April’s election when Ciudadanos won 57 seats and the Socialists 123, giving the two of them an absolute majority, but Rivera refused even to discuss an alliance, even though the two parties agreed after the 2015 election when they had 130 seats a wide-ranging pact (which did not gain sufficient support from other parties). That pact could easily have been revived.

Figure 3. Possible majorities (total seats)

| Total seats | Absolute majority | |

|---|---|---|

| Socialists+Ciudadanos+Popular Party abstention | 218 | 176 |

| Socialists+Popular Party | 208 | 176 |

| Socialists+Unidas Podemos+Más País+Basque Nationalist Party+other regional parties (excluding the Catalans) | 170 | |

| Socialists+Unidas Podemos+ Más País | 158 | 176 |

| Popular Party+VOX+Ciudadanos | 150 | 176 |

Source: Spanish Ministry of Interior.

Felipe González, the Socialist Prime Minister who presided over stable governments between 1982 and 1996 and generally majority ones, quipped last month that Spain has an ‘Italian parliament’ in terms of fragmentation, but no ‘Italian politicians’ to master it.

One can only hope he is proved wrong this time, as Spain has many issues that need resolving – from a pensions system in crisis to a still high level of unemployment and the thorny issue of Catalan independence that shows no signs of going away.