Theme

Spain finally has a functioning government, following two inconclusive elections, and the country’s first coalition administration since the Second Republic in the 1930s. Pedro Sánchez, the Socialist caretaker Prime Minister, was only able to form his minority government with Unidas Podemos (UP) a hard-left party, by the narrowest of margins. The government faces a raft of challenges including continued high unemployment in a slowing economy, fiscal consolidation, population ageing and its impact on the sustainability of the welfare state, and the Catalan independence conflict.

Summary

Politically, modern Spain is in uncharted territory as it has no experience of coalition governments. Until its uneasy formation, Spain was the only EU country apart from Malta that had not had such a government in the last 40 years. Keeping it afloat will be taxing, in the face of virulent opposition from the right. The most immediate economic issue is to secure parliamentary approval for the 2020 budget. The 2018 budget had to be rolled over last year, making 2019 another wasted year in fiscal consolidation. Unemployment remains stubbornly high in a slowing economy. The welfare state is coming under increasing strain, particularly on the pensions front. In education, the early school-leaving rate is still well above the EU average. In foreign policy, one of the first challenges will be to negotiate the future of Gibraltar, the British overseas territory, after the UK leaves the EU on 31 January. Last but by no means least, the Catalan independence conflict shows no signs of abating.

Analysis

Background

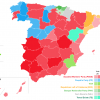

The Socialists were the most voted party in the elections last April and November, but far short of a majority. They won 123 of the 350 seats in April and 120 in November. The November general election was the fourth in as many years (a record for an EU country), and produced an even more fragmented parliament (19 parties are represented, see Figure 1).

The April election was called because Pedro Sánchez, who had come to power in June 2018 after winning a censure motion against the Popular Party (PP) government of Mariano Rajoy, failed to get sufficient support for his 2019 budget, and the November one because of the Socialists’ veto on entering into a coalition with UP and the refusal of the centre-right Ciudadanos (Cs) to countenance a pact with the Socialists.

The latter was an historic mistake as between them the two parties had an absolute majority after the April election (180 seats), which would have guaranteed a much more stable and reformist government than the one which Sánchez was forced to forge with UP in a humbling climbdown, following his admission last September that he would not be able to sleep if UP was part of his government. UP captured 35 seats, seven fewer than in April. The new administration is the only wholly left-wing government in the EU (Italy’s centre-left Democrats have a coalition with rightish Five Star Movement).

Sánchez won the second investiture vote on 7 January by a hair’s breadth (167 votes to 165, with 18 abstentions), when only a simple and not an absolute majority was required. The 13 MPs of Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC), the largest Catalan separatist party abstained in return for open-ended talks on the Catalan independence conflict, and the other five abstentions came from Bildu, the Basque party, among others, of the former terrorists of ETA. Obtaining the passive support of these two parties outraged the three parties on the right – the PP, Cs and the far-right VOX (between them they have 150 seats) – which aggressively labelled the new administration a ‘Frankenstein government’ as they claimed it would be beholden to the Catalan separatists. This bloc will give the coalition no quarter in what will be the most ill-tempered parliament since democracy was restored in 1978.Figure 1. Results of general elections, November 2019 and April 2019 (seats, millions of votes and % of total votes)

| November 2019 | April 2019 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seats | Votes | % | Seats | Votes | % | |

| Socialists | 120 | 6.75 | 28.0 | 123 | 7.48 | 28.7 |

| Popular Party | 88 | 5.01 | 20.8 | 66 | 4.35 | 16.7 |

| VOX | 52 | 3.64 | 15.1 | 24 | 2.67 | 10.3 |

| Unidas Podemos (1) | 35 | 3.09 | 12.8 | 42 | 3.73 | 14.3 |

| Catalan Republican Left | 13 | 0.86 | 3.6 | 15 | 1.01 | 3.4 |

| Ciudadanos | 10 | 1.60 | 6.8 | 57 | 4.13 | 15.9 |

| J×Cat (2) | 8 | 0.52 | 2.2 | 7 | 0.49 | 1.9 |

| Basque Nationalist Party | 7 | 0.37 | 1.6 | 6 | 0.39 | 1.5 |

| EH Bildu | 5 | 0.27 | 1.1 | 4 | 0.25 | 1.0 |

| Más País (3) | 3 | 0.50 | 2.1 | – | – | – |

| CUP | 2 | 0.24 | 1.0 | – | – | – |

| Canarian Coalition | 2 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.13 | 0.5 |

| Navarra Suma | 2 | 0.09 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.10 | 0.4 |

| BNG | 1 | 0.10 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.09 | 0.4 |

| PRC | 1 | 0.06 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.2 |

| Compromis (3) | – | – | – | 1 | 0.17 | 0.6 |

| Teruel Existe | 1 | 0.02 | 0.08 | – | – | – |

| Voter turnout (%) | 69.9 | 75.8 |

(1) Unidas Podemos: Podemos-IU, En Comú Podem and Podemos-EU; (2) Junts per Catalunya: CDC and PDeCAT; and (3) Más País presented candidates in 18 provinces in coalition with Equo, Compromis and Chunta Aragonesista.

Source: Interior Ministry.

The ERC wasted no time in making it clear the government should not take its support for granted. The ERC MP Montserrat Bassa told parliament she ‘didn’t care a damn about the governability of Spain.’ Her sister Dolors was one of nine Catalan leaders sentenced last October by the Supreme Court to between nine and 13 years in prison for their role in organizing in 2017 an illegal referendum on Catalan independence and a unilateral declaration of secession by the region’s parliament.

UP has five of the 23 cabinet seats. Pablo Iglesias, Podemos’ leader, is one of four Deputy Prime Ministers, responsible for social rights and the 2030 Agenda, and Alberto Garzón, the leader of United Left is Minister of Consumer Affairs. The

coalition’s programme includes the following proposals:

- Income tax for those earning more than €130,000 a year to rise by two percentage points, and by four for those who earn more than €300,000. Capital gains tax to increase from 23% to 27% for above €400,000. New minimum corporate tax rate of 15% and 18% for banks and energy utilities. A separate tax will target stock market transactions.

- Lift the minimum wage to 60% of the average national wage by the end of the government’s four-year term, from around 45% now.

- Continue to reduce the fiscal deficit and public debt.

- Shield health, education, security and social support from privatization.

- Open a dialogue on the future of Catalonia, with a popular vote in the region, but any negotiations must abide by the 1978 constitution, which upholds Spain’s territorial integrity.

- Roll back the PP’s labour market reform which gives priority to company-level bargaining over sectoral agreements.

- Introduce a price index to limit abusive renting practices, and strengthen the role of the state-owned bank Sareb in subsidized housing.

- Eliminate the gender pay gap.

- Declare 31 October as a remembrance day for all victims of Franco’s 1939-75 dictatorship.

Fiscal consolidation not yet achieved

The government’s first economic priority will be to draw up and get parliamentary approval for a 2020 budget. It was the failure to get agreement for the 2019 draft budget that triggered last April’s election. The ERC, back supporting the Socialists, joined forces with the three parties in the right wing bloc in defeating that budget. As a result, the 2018 budget had to be rolled over. Public spending nevertheless increased last year as a result of the measures approved through Royal Decree-Law, making it another wasted year in terms of fiscal consolidation.

Spain was finally released last June from the European Commission’s excessive deficit procedure, as the 2018 fiscal deficit came in, for the first time in a decade, at below the EU threshold of 3% of GDP (see Figure 2). The deficit had peaked at a whopping 11% in 2009. The European Commission forecasts the 2019 deficit at 2.3%, much higher than the 1.3% agreed by the Rajoy government with Brussels. The high fiscal deficit and the level of public debt (close to 100% of GDP) mean the coalition government has little leeway in fiscal policy. Not surprisingly, it wants to negotiate a new deficit target with Brussels for 2020, well above that of the PP’s 0.5%. Without it, Sánchez will not be able to meet his spending promises.Figure 2. Spain’s budget balance, 2008-2019 (% of GDP)

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -4.42 | -11.02 | -9.45 | -9.31 | -6.79 | -6.67 | -5.84 | -5.23 | -4.29 | -3.07 | -2.5 | 2.3 |

(*) Estimate.

Source: Eurostat.

The continued presence in the government of Nadia Calviño, a former director general of budget at the European Commission, as Economy Minister, has sent a positive signal to Brussels that fiscal matters are in a safe pair of hands. Calviño is now one of four deputy prime ministers.

The pressure to cut the deficit comes at a time when the economy is slowing down. GDP has expanded every year since 2014, following the Great Recession, but last year grew at its slowest pace (around 2%), albeit still above the euro zone average (1.2%). Growth this year is put at around 1.7%. The contribution of domestic demand to GDP growth has weakened and that of external demand has fallen sharply. The impact of the US-China trade war, the new tariffs imposed by the US on the EU and specifically on Spain and Brexit uncertainty are affecting exports. The Bank of Spain estimates that the protectionism of the US and China will shrink Spain’s GDP by 0.2 percentage points.

Unemployment remains stubbornly high

Unemployment at 14%, almost double the euro zone average, has virtually stopped falling after peaking at 26% in 2013, and the jobless rate for those under the age of 25 is still more than 30% (see Figures 3 and 4). The fall in the overall rate in 2019 was the lowest since 2013, and job creation slowed to 2%, below the high point of 3.4% in 2017. In the third quarter of last year, 26.7% of jobholders were on temporary (i.e. precarious) contracts, 4.7 percentage points higher than the record low hit in the fourth quarter of 2012.Figure 3. EU seasonally adjusted unemployment rates, November 2019 (%)

| % | |

|---|---|

| Greece | 16.8 |

| Spain | 14.1 |

| Italy | 9.7 |

| France | 8.4 |

| Euro zone | 7.5 |

| Portugal | 6.7 |

| United Kingdom | 3.7 |

| Germany | 3.1 |

Source: Eurostat.Figure 4. EU youth unemployment rates, October 2019 (%)

| % | |

|---|---|

| Spain | 32.8 |

| Greece | 32.5 |

| Italy | 27.8 |

| France | 19.0 |

| Euro zone | 18.3 |

| United Kingdom | 11.4 |

| Germany | 5.8 |

Source: Eurostat.

Overturning the PP’s labour reform which gave priority to company-level bargaining over sectoral agreements, a measure that gave firms flexibility and enabled some of them to withstand the recession and keep jobs, will probably have the opposite effect of creating employment.

The government also wants to increase the minimum annual wage to 60% of the average national wage by the end of its four-year term in office from the current 45%. Spain’s minimum wage is among the lowest in the EU (see Figure 5).Figure 5. Minimum wage in the European Union (net annual wage in euros)

| € | |

|---|---|

| Denmark | 27,341 |

| Luxembourg | 21,489 |

| Ireland | 18,535 |

| United Kingdom | 18,184 |

| Italy | 16,679 |

| France | 14,194 |

| Germany | 13,810 |

| Spain | 11,573 |

| Bulgaria | 2,902 |

Source: Eurostat.

Welfare state under strain

The moment of truth is coming for Spain’s welfare state, created over the last 40 years. The rapidly ageing population and longevity are exerting pressure on the sustainability of the healthcare system and the viability of the state pension system. Spaniards are living almost 10 years longer today than they did 40 years ago. Life expectancy at birth is 83 years, the second highest in the world after Japan and set to overtake that country by 2040. In 2050 35% of the population in Spain will be over the age of 67 compared with 16.5% today. The affiliate-to-pensioner ratio has dropped from 2.71 social security affiliates per pensioner in 2007 to 2.31 (1.26 in 2050, according to the European Commission). The baby boom generation begins to retire in 2022. Within a decade, unless there is a significant demographic change, only around 400,000 people will be entering the labour market every year whereas between 700,000 and 800,000 will be retiring annually. Either policies are introduced to increase the very low fertility rate of 1.33 children (below the replacement rate of 2.1) or Spain is going to need another big influx of immigrants. Deaths have outstripped births for the last three years.

The social security deficit (more than €18 billion since 2016), which includes the unemployment benefits for the large number of jobless, accounts for more than 55% of the total fiscal deficit. Reducing it is the key to improving Spain’s fiscal position, but it will not be easy or popular in a country with expectations rising as a result of the sustained recovery from the recession and demands for greater social protection. José Luis Escrivá, the Minister of Social Security, Inclusion and Migration and the former head of Spain’s Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility, has a tough job on his hands.

Spending on old age, unemployment, housing and social exclusion, healthcare and family account accounted for 23.4% of GDP in 2017, down from 25.7% in 2012, much lower than the EU average of 27.9% (latest comparative figures, see Figure 6). Old age and survivors accounts for a much bigger chunk of total social protection expenditure than the EU average (51.6% vs. 45.8%). The tax burden is still below the peak in 2007 and much lower than the EU average (see Figure 7).Figure 6. Top five countries and Spain in social protection (% of GDP)

| % | |

|---|---|

| Denmark | 32.2 |

| Finland | 30.6 |

| Germany | 29.7 |

| Austria | 29.4 |

| Netherlands | 29.3 |

| Spain | 23.4 |

Source: Eurostat.Figure 7. Tax revenue-to-GDP ratio (including social security contributions), 2007 and 2018 (%)

| 2007 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|

| France | 44.5 | 48.7 |

| Germany | 39.3 | 41.5 |

| Italy | 41.5 | 42.0 |

| Spain | 37.3 | 35.4 |

| UK | 35.0 | 35.1 |

| EU average | 39.2 | 40.3 |

Source: Eurostat.

A PP reform which came into force in 2014 stopped pensions being automatically indexed to inflation every year. The annual rise was set at 0.25%, with a maximum increase capped at 0.5% above inflation, if the system could afford it. The statutory retirement age is also being gradually increased from 65 to 67 as of 2027, for both men and women. The coalition’s first measure was to increase pensions this year by 0.9% in order to ensure retirees do not lose purchasing power. At the same time, the reserve fund created in 2000 and built up during the years of the economic boom to help pay future pensions, which peaked at €66.8 billion in 2011, has virtually been depleted.

Time or a shake-up in education

One of the positive results of Spain’s Great Recession has been the considerable reduction in the country’s early school-leaving rate, as students had little option but to stay on at school after 16, but at 18% it is still the second highest in the EU after Malta (see Figure 8). Many of those who dropped out of school early were repeaters at the lower secondary level: Spain has the largest share of these repeaters across all OECD countries (11% compared with an average of 2%).Figure 8. Early leavers from education and training (% of population aged 18-24)

| 2018 | 2006 | |

|---|---|---|

| Spain | 17.9 | 30.3 |

| Protual | 11.8 | 38.5 |

| Italy | 14.5 | 20.4 |

| UK | 10.7 | 11.3 |

| EU-28 | 10.6 | 15.3 |

| Germany | 10.3 | 13.7 |

| France | 8.9 | 12.4 |

Source: Eurostat.

There are various factors behind the high dropout rate, including spending on education that is lower than the EU average of 5% of GDP (4.2%), poorly qualified teachers, the rote system of learning, and the failure of the political class as a whole to agree lasting reforms that are not reversed when the political colour of the government changes. The attempt to agree a state pact on education, supported by the main parties, broke down in May 2018.

Universities also need shaking up. Only five made it into the latest top 300 ranking by the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU). Generally speaking, universities are weighed down by bureaucracy, degrees that take longer to obtain, precarious staffing (many teachers on temporary contracts) and a failure to attract foreign talent or repatriate Spaniards who find better paid and more attractive academic jobs abroad.

Climate change vanguard

Spain, which successfully hosted in December the UN summit known as COP25, can claim to be in the vanguard of the fight against climate change (see Figure 9), but it has yet to have a law on the issue.

With Peru, the country heads the coalition of social and political drivers that is mobilising UN member states to work towards sustainable economic change, and it has the EU’s best national ecological transition plan, according to the European Climate Foundation’s assessment of drafts submitted to the European Commission. The government, with a Deputy Prime Minister for the Ecological Transition, wants to introduce a climate change bill to make all towns with over 50,000 inhabitants create low-emission zones.Figure 9. Spain and the fight against climate change

| Spain and the UN’s 2020 Agenda | 21st out of 162 countries in implementation of sustainable development goals (SDGs). Score of 77.8/100, similar to Canada, Iceland and Switzerland |

|---|---|

| Environmental Performance Index (EPI) | 12th out of 180 countries (1st in water and sanitation, 13th in biodiversity and habitat and 20th in air quality) |

| Renewable energy | 12th in renewable energy production capacity, 5th in installed wind capacity and 10th largest producer of photovoltaic energy, International Renewable Energy Agency |

| Environment in Spain | 1st country worldwide in biosphere reserves and 2nd in UNESCO parks |

The virtual ending of coal in 2019 to produce electricity resulted in a 33% fall in carbon dioxide emissions, one of the primary greenhouse gases. Unprofitable coal mines worked their last shifts at the end of 2018 under a European Union directive in which deposits that longer made money and received public funds had to stop production by 1 January 2019. As a result, 26 uncompetitive mines closed. Coal accounted for less than 5% of Spain’s energy needs last year.

Keen to be more assertive on the European stage

The lack of a functioning government for most of last year prevented Spain from being more active on the world stage. This did not, however, affect the candidacy of Josep Borrell, the former Foreign Minister, who was appointed to the top EU diplomacy job. The new government, and Borrell in particular, is keen to play a more prominent role on the European stage, promoting closer union on migration, decarbonization, social rights and the single market.

‘Spain is back, Spain is here to stay,’ Arancha González Laya, the new Foreign Minister, said on taking office and deliberately in English ‘so that the world will hear us loud and clear’ (said in Spanish). The multi lingual Gonzalez Laya is the former executive director of International Trade Centre

One of its first challenges will be to negotiate with the UK the future of Gibraltar, the British overseas territory perched on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula and long claimed by Spain, after the UK leaves the EU. Gibraltar, ceded to Britain under the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, voted overwhelmingly (95.1%) in the 2016 Brexit referendum to remain in the EU.

The resounding victory of the Conservative Party under Boris Johnson in the UK election in December means that the four memorandums of understanding (MoUs) signed in 2018 between Gibraltar, the UK and Spain and the protocol in the withdrawal agreement, which had underpinned Gibraltar’s position after Brexit, are back on the table. They were conditional on the UK achieving a negotiated exit from the EU, which takes place on 31 January. The MoUs ensure the Rock’s orderly withdrawal and set out a time-limited framework for cooperation with Spain on issues such as cover citizens’ rights, environmental matters, cooperation in police and customs matters and tobacco and other products.

The MoUs are only for the duration of the transition period, by the end of which on 31 December, the UK is supposed to have agreed its new relationship with the EU. Johnson has said this date will not be extended, although few believe 11 months is enough time to negotiate such a complex matter. Gibraltar has made it clear that it must be part of the negotiation process related to the Rock, and it would walk away if any deal had sovereignty implications as the price for inclusion. Any agreements between the EU and the UK in respect of Gibraltar after Britain leaves the bloc require Madrid’s prior agreement.

Both sides want to ensure that Gibraltar’s departure from the EU does not negatively affect the lives of those who cross the order in either direction. Some 12,000 cross from Spain every day to work in Gibraltar, mostly Spaniards.

Catalonia crisis rumbles on

The Catalan independence conflict was a dominant issue in last year’s elections, particularly in the case of the far-right party VOX which more than doubled its number of MPs in November’s elections to 52 out of a total of 350. And with no end in sight to the conflict that began in October 2017 with an illegal referendum on independence and a unilateral declaration of secession by the region’s parliament, the crisis is going to dog the coalition.

The government was only formed, and by the slimmest of margins, because the 13 MPs of Catalan Republican Left (ERC), the largest of the pro-independence parties, agreed to abstain in the second investiture vote in return for talks. Junts per Catalunya (JxCat), the other and less pragmatic secessionist party, with eight MPs, which is in coalition with ERC in the Catalan government, felt betrayed and voted against the Socialist-led administration. Oriol Junqueras, the ERC leader and the former Catalan Vice-President, is serving a 13-year jail sentence for sedition and Quim Torra is the JxCat President.

The Catalan conflict has become more international since the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled last month that Junqueras should have been given immunity to take up his seat in the European Parliament. He was elected in May while in detention and ahead of the conclusion of the trial in October. The ECJ said that if Spanish courts had wanted to keep him in detention to prevent him from travelling to the European Parliament for his inauguration, they should have requested that Parliament waive his immunity. However, the court said Spain’s Supreme Court should decide how to apply the ruling given that Junqueras’ status had since changed from that of suspect to convicted felon. Not surprisingly, the Supreme Court ruled against setting Junqueras free. ‘He who participates in an electoral campaign while already on trial, even if eventually elected, does not enjoy immunity from national law,’ the court ruling said.

Two other top Catalan separatists were elected as MEPs in May and the ruling affected them too. Former Catalan President Carles Puigdemont and Toni Comin fled to Belgium before Spain could detain them. The European Parliament allowed them to take up their seats earlier this month, from where Puigdemont will do his utmost to make the Catalan crisis a European question.

Spain’s Supreme Court formally asked the European Parliament to strip Puigdemont and Comín of their immunity as MEPS. VOX waded into the controversy and announced it would sue the Parliament for having recognised them as MEPs.

Torra meanwhile was barred from holding public office for 18 months because he refused to remove separatist symbols from public buildings during an election campaign. The court’s ruling will only become effective if confirmed by the Supreme Court, something that might trigger a snap election in the region. Pro-independence parties have a slim majority in the Catalan parliament, but secession does not have majority support among the wider public.

The coalition’s agreement with ERC in return for the party’s passive support of its formation is highly ambiguous. The party signed up to it because it proposes a referendum on self-determination, but the government can reject it as it is unconstitutional. This, of course, assumes that the talks do not break down.

Conclusion

Spain has come through worse times, and to do so the political class needs to do much more to put aside its differences and compromise for the good of the country as a whole – a tall order!

William Chislett

Senior Research Fellow, Elcano Royal Institute | @WilliamChislet3