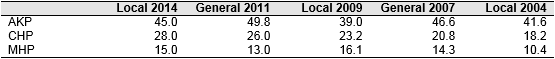

Turkey’s embattled Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, reeling from allegations of corruption and massive protests against his authoritarian rule last year, swept the board in local elections and increased the share of the municipal vote of the ruling Justice and Development party (AKP) from 39% in 2009 to 45% (see Figure 1).

Although lower than the 50% share of the vote in the 2011 general election, the victory of the Islamist-rooted AKP was very much a personal and stunning victory for Erdogan as he successfully turned the local election into a personal referendum.

AKP= Justice and Development Party; CHP= Republican People’s Party; MHP=Nationalist Action Party.

Source: Supreme Electoral Board.

Emboldened by the result on a voter turnout of around 90%, an exceptionally high figure for local elections, Erdogan thundered from the balcony of the AKP’s headquarters in Ankara that he would go after his enemies. ‘We will not surrender to Pennsylvania and their offshoots in Turkey. From tomorrow, there may be some who flee, there are some who already fled. We will enter their lair. They will pay for this. They will pay the price’.

This was a clear reference to Fethullah Gülen, the US-based moderate Muslim cleric and former ally of Erdogan, who is believed to be behind a flood of leaked tape-recordings posted on YouTube and Twitter detailing the purported shady business dealings of Erdogan, his children and senior AKP officials that have gripped the public, as well as Erdogan’s silencing of critical media.[1]

Erdogan personally ordered the blocking of Twitter before the local election (overruled by a Turkish court and condemned by Abdullah Gül, the Turkish President) and banned YouTube.

The Sufi-inspired Gülen fled Turkey in 1999, apparently fearing he would be arrested for plotting against the secular state. He runs a global network of schools, media outlets and charities and his followers are said to be occupy strong positions in the police and judiciary.

Erdogan raised the possibility of requesting Gülen’s extradition from the US on the grounds of interference in Turkish affairs. Although Turkey is an important strategic ally for Washington, it is highly unlikely it would agree to such a request. The Obama administration has become increasingly worried at Erdogan’s authoritarian drift and erratic behaviour, which has stymied the country’s accession negotiations to join the EU.

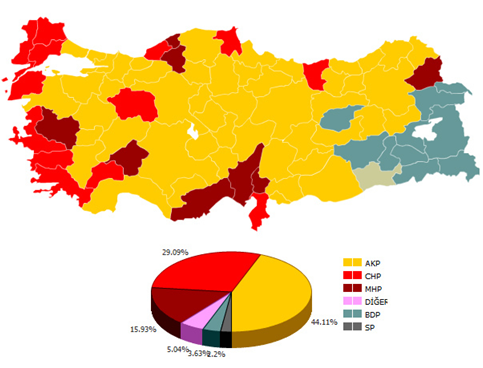

The centre-left Republican People’s Party (CHP), established by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the secular Turkey Republic in 1923 from the ruins of the Ottoman Empire, and the right-wing Nationalist Action Party (MHP) failed to make much headway against the AKP (see Figure 2). The AKP managed to hold on to both Istanbul, the largest city and the one from where Erdogan, as mayor (1994-98), began his political ascendance, and Ankara, the country’s capital. The other winner is the pro-Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party (BDP) which increased the number of cities it controls in the mainly Kurdish south-east region from eight to 11 at the expense of the AKP.

The CHP and the MHP could not match the AKP’s formidable vote-catching machine which steamrolled through the country garnering support. The AKP also benefited from the economic prosperity created over the last decade, although this is beginning to wane.

Turkey’s stellar growth slowed to just above 2% and inflation rose to 7.4% in 2013. The country’s currency slumped earlier this year, forcing Turkey’s central bank into a U-turn when it hiked interest rates in a bid to discourage foreign capital outflows. The economy is too reliant on hot money, which can leave as quickly as it arrived. The economy could become the AKP’s Achilles heel.

Although this was a local election, Erdogan treated it as if he was running for Prime Minister again. He barnstormed around the country with some 60 rallies and presented the electoral contest as a fight with the ‘traitors’ of the so-called ‘parallel state’ in what he termed Turkey’s ‘second war of liberation’. The first one was fought by Atatürk against foreign occupying armies.

The alliance with Gülenists served Erdogan well after he became Prime Minister in 2003 with 34% of the vote, a major shock for the so-called ‘deep state’ (a shadowy network of elites in the armed forces, the judiciary and the government bureaucracy).

Gülen supporters in the judiciary and police, long-established bastions of the secular order, went after alleged coup plotters and those associated with the ‘deep state’ in high profile trials known as Ergenekon and Sledgehammer that were widely believed to be based on flimsy evidence in some cases.

In 2012 and 2013 hundreds of people were given prison sentences, including many high-ranking officers in the once all-powerful military, the traditional arbiter of political life which staged three coups against elected governments between 1960 and 1980 and got rid of another government in 1997 (a precursor of the AKP) after issuing a memorandum against it. There was also a move by the military against the AKP in 2007, which backfired as Erdogan called a snap election.

Erdogan appears to be invincible and shows every sign of continuing his majoritarian concept of democracy, a trait also common to Vladimir Putin, the Russian President. Riding on a crest of popularity, the way is open for him to run for President in the first direct elections in August, a post he hankers after but one that will not have the increased French-style powers that he would like as the AKP does not have the required two-thirds support in parliament to push through reforms.

This leaves the possibility of seeking a fourth term as Prime Minister if Erdogan changes AKP bylaws that limit leaders to three terms. His current term ends in May 2015. If, as assumed, he wants to keep executive power and maintain control of the AKP, rather than be President with limited powers, the premiership is the option that would most suit him. Either way, Erdogan is here to stay.

[1] In one of the recorded conversations, Erdogan reprimanded Fatih Sarac, an executive at Habertuk, a popular news channel, for airing the views of an opposition leader. Sarac, a close associate of Erdogan, apologised and within a couple of minutes the person was taken off the air. Erdogan admitted this conversation.