On 21 January 2026 the European Parliament approved a request for an opinion from the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) on the EU-MERCOSUR Association Agreement. The decision does not challenge the political or economic substance of the agreement, but rather its legal validity under EU law, in particular the legal basis and the procedure chosen for its negotiation and approval. Specifically, Parliament is asking the Court to determine whether the agreement, as currently structured, is compatible with the Treaties, that is, with the fundamental rules governing the allocation of competences between the EU and its Member States, the procedures for concluding international agreements and the institutional balance between the EU’s main institutions.

The challenge before the CJEU does not spell the end of the EU-MERCOSUR agreement, but it does introduce an element of unpredictability.

The ‘splitting’ of the agreement and national parliamentary scrutiny

One of the two central elements of the legal challenge is the so-called ‘splitting’ of the agreement. The European Commission, with the backing of the Council of the European Union, has chosen to divide the EU-MERCOSUR agreement into two separate legal instruments. On the one hand, a trade component of the agreement, considered to fall under the EU’s exclusive competence and therefore subject only to approval by the Council of the EU and the European Parliament. On the other hand, an Association Agreement that includes not only the trade component but also the political and cooperation components, which does require ratification by the national parliaments of the Member States.

MEPs who promoted the challenge argue that this division is legally questionable. From this perspective, the splitting would make it possible to bypass national parliamentary scrutiny over provisions with far-reaching effects in areas such as agriculture, the environment, health regulation or labour standards. Parliament is asking the CJEU to clarify whether this fragmentation complies with the Treaties or whether, on the contrary, it infringes the principle of conferral of competences and the balance between the EU and its Member States.

The rebalancing mechanism and the EU’s regulatory autonomy

The second pillar of the challenge concerns the so-called ‘rebalancing mechanism’ included in the agreement. The mechanism would allow MERCOSUR countries to adopt compensatory measures if future EU regulatory decisions –for example in environmental, climate or health matters– were to result in a significant reduction of their exports to the European market.

Critics argue that this clause goes beyond a traditional trade instrument and could, in practice, affect the EU’s regulatory autonomy by exposing it to challenges or retaliation if it adopts new, legitimate public-interest regulations. What is being questioned legally is not the existence of adjustment mechanisms per se, but the fact that third countries could indirectly condition future EU regulatory decisions, which, according to the proponents of the challenge, could be at odds with the Union’s regulatory sovereignty as enshrined in the Treaties.

A narrow vote and a cross-cutting majority

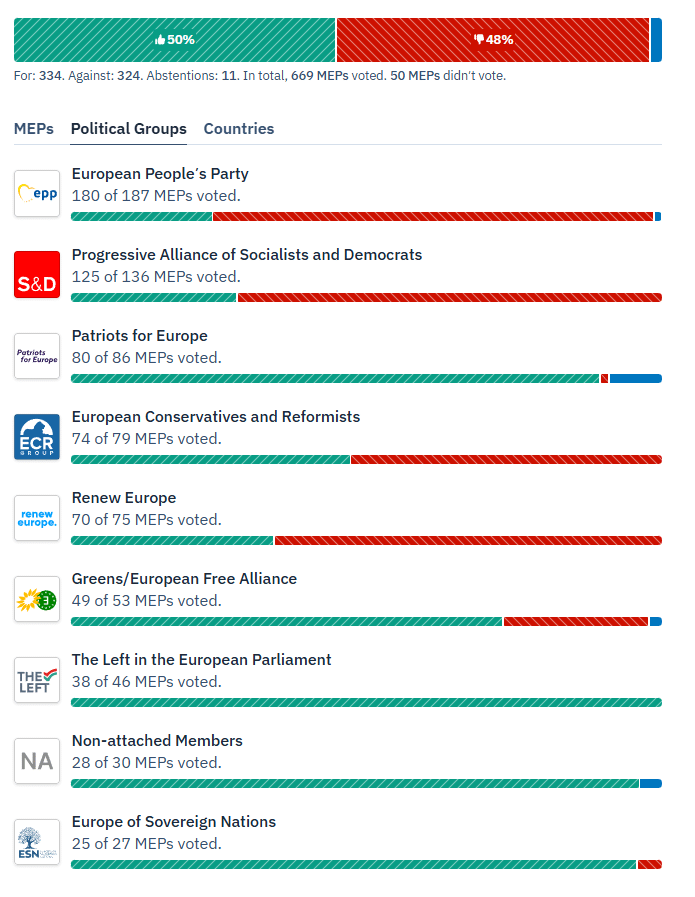

The request for an opinion from the CJEU had to be approved by the European Parliament in a plenary session, as it concerns an institutional prerogative of Parliament as a whole. The result was extraordinarily close: 334 votes in favour, 324 against and 11 abstentions, which had the immediate effect of suspending the parliamentary approval procedure for the agreement until the Court delivers its opinion.

The challenge was supported by a cross-cutting coalition. The initiative was driven by the Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA) and The Left in the European Parliament–GUE/NGL (The Left) and received support from the Patriots for Europe (PfE) Group. Renew Europe (Renew) –which brings together liberal parties– was divided, with national delegations such as the French and Belgian ones supporting the challenge, while others argued in favour of a rapid ratification of the agreement. Isolated defections were also recorded within the European People’s Party (Christian Democrats, EPP) and the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D), while the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) granted freedom of vote (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Results of the vote on the request for an opinion from the Court of Justice on the compatibility with the Treaties of the EU-MERCOSUR Association Agreement (EMPA) and the proposed Interim Trade Agreement (ITA)

The outcome of the vote on the challenge provides a preliminary indication of the political balance surrounding the agreement, but it does not automatically foreshadow the result of a future ratification vote in the European Parliament, as some MEPs supported judicial scrutiny as a legal precaution rather than as a substantive rejection of the agreement.

The judicial timetable and possible scenarios

The referral to the CJEU effectively postpones ratification of the agreement by the European Parliament. Although a vote had been envisaged for spring 2026, advisory opinion procedures before the Court typically last more than a year. The Court could opt for an in-depth examination of the allocation of competences and the institutional design of the agreement, which would reinforce a lengthy timetable. There is, however, the possibility of an expedited procedure, given the political and strategic nature of the agreement.

From a legal standpoint, the Court could validate the legal architecture proposed by the Commission and the Council, require limited adjustments or, in a more disruptive scenario, question the legal basis of the agreement as currently conceived.

A provisional entry into force

In parallel with these parliamentary and judicial dynamics, the Council of the European Union –which represents the Member States– had already authorised the European Commission to sign the EU-MERCOSUR agreement, which effectively took place on 17 January in Asunción. Following the European Parliament’s vote requesting the CJEU opinion, the European Council –a distinct institution composed of Heads of State or Government– expressed its political support for the possibility of a provisional entry into force of the agreement.

This option would allow the provisional application of the trade agreement –an area of exclusive EU competence– once at least one MERCOSUR parliament has completed its ratification, even while the CJEU examines the legality of the procedure. In this way, the European Commission places itself at the centre of the process as promoter and executor of the agreement, in a context of interinstitutional tension over timing, legal safeguards and democratic control of the treaty.

The reaction of MERCOSUR countries

The European Parliament’s decision was received with concern and caution in the MERCOSUR countries. Governments in the region stressed that the agreement had been renegotiated and concluded after more than two decades of negotiations, and that the legal challenge introduces a new element of uncertainty. Some governmental and business actors expressed fears that recourse to the CJEU could become a delaying tactic, while others emphasised that European judicial review is an internal EU matter over which MERCOSUR has little influence.

In this context, several MERCOSUR governments stated their intention to submit the agreement to their respective parliaments as soon as possible, with the aim of advancing national ratifications and exerting political pressure on the EU to activate the provisional application of the treaty. Overall, reactions have combined a defence of the agreement with a call for the EU to swiftly clarify its institutional position.

Conclusions

The challenge before the CJEU does not spell the end of the EU-MERCOSUR agreement, but it does introduce an element of unpredictability. In the short term, it delays parliamentary ratification; in the medium term, the Court’s opinion will be decisive in shaping how the EU can conclude major trade agreements in the future, reconciling its geopolitical ambition to be a key player in the new international order as a champion of cooperation and rules-based trade –as embodied in agreements of this kind– with legal certainty and democratic legitimacy.