Theme

Brussels is gaining influence and political clout in the world although Washington remains the focal point of international politics.

Summary

Relations between think tanks and their various analysts on Twitter can provide a digital pointer to how political influence is evolving following recent international events such as Brexit, Donal Trump’s election as US President and the re-emergence of Russia as a player on the international scene. The advent of the digital era and the new trends in international politics have led think tanks to understand and interpret the world scenario in accordance with their objectives and to adjust their influence accordingly. Thus, influence has found its place on the net.

Looking at how think tanks engage with each other on Twitter shows much about their nature and structure. Networks are global but power is exerted at the local level. Analysing think-tank trends in the network of influencers can help understand the processes and research projects in which they are involved. Why is London losing influence as a hub to Brussels’ benefit? It is paradoxical that while the European project seems in doubt, Brussels is actually flourishing in terms of influence and power.

Analysis

What is the purpose of a think tank and what kind of explicit goals do these institutions need to account for in their yearly overview? A think tank must produce and commit itself to ideas; identify possible recipients for said ideas and sell them with regards to a policy oriented cost-benefit analysis. Thus, political influence is found to be an inherent facet of every think tank, where ‘influence’ is understood as the process of generating tendencies within ideas and transforming them into policy propositions for the decision-takers.

In order to understand organised interests and influencer dynamics we must ask ourselves: how do think tanks achieve political influence within policy-makers? During the 20th century, lobbyists and interest groups have been researched by sociologists, political scientist and economists such as Scott Ainsworth, David Austen-Smith and Peter M. Haas, with his analysis of Epistemic Communities. Similarly to their counterparts in the previous century, 21st-century think tanks have not had a different political approach.

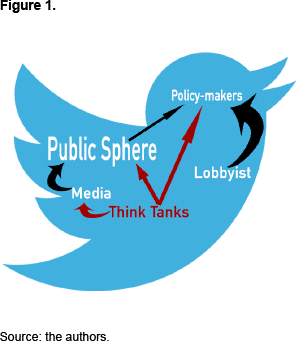

However, with the changes brought about by the digital era, think tanks increasingly tend to expand their audiences and broadcast their information through the web and into the public sphere. Consequently, this makes them direct competitors of the media given their status of ‘expert researchers’.

However, influence is contextual and the digital context of the 21st century makes the policy processes of think tanks different. As stated by Joseph Nye, the digitalization process, a concept thoroughly discussed and debated over the past 15 years that has direct implications on the definition of power –a concept closely linked to influence–, has a direct effect on modern diplomacy processes.

This Diplomacy 3.0 which Nye alludes to recognises the power in the citizens’ ability to communicate, interact and connect with other citizens or public institutions, politicians and civil servants available on the social web. Additionally, policy-makers see within these networks a way to better understand the societies which they govern. This is what Philip Seib defines in his Real-Time Diplomacy work as a basic and transparent element for the exercise of democracy.

21st century think tanks position themselves within this digital context, using networks in order to spread messages, ideas, policy recommendations and the establishment of relationships between each other. Now however, their targets are not just policy-makers anymore. Think tanks also seek to influence the media and two elements that, according to Jürgen Habermas, characterise civil society: non-governmental institutions and social movements.

Furthermore, even if access to information has drastically improved during the past 15 years, technological resource management allows 21st century think tanks to manage their communication strategies in order to create competitive advantages. Additionally, good communication strategies are found to be key elements within the objectives of both think tanks and lobbyists with the purpose of gaining access to networks of political influence.

In order to measure the political influence of think tanks, different variables must be taken into account for different contexts. In this regard, it is useful to apply Scott Ainsworth and Randolph Sloof’s game-theory model, which was used to analyse the relationships between lobbyists and policy-makers in the early 90s. The academic debate revolves around the complexity of analysing qualitative variables such as prior beliefs, information levels, order of moves and structure of communication and reputation on think tank influence, which can be applied both to 20th century lobbyists and 21st century think tanks.

In this regard, there is scant research analysing and quantifying think-tank influence. Gotothinktank.com, a University of Pennsylvania project, stands out due to its impact within the field. Its research, however, relies on questionnaire-based methodologies in order to generate several rankings within different fields that are categorised by elements of image and reputation, thereby ignoring levels of information, communication structures and ideological analysis.

Reputation analysis within international relations and public policy research is found to be useful for the measurement of political influence levels. However, if the purpose is to obtain comparative conclusions between think tanks, this methodology lacks sufficient variables to properly contextualise such influences.

For Patrick Bernhagen the process of influencing consists of the lobbyist’s relationships with policy makers, the policy-makers’ commitment to the policy and the expected costs for reformulating the policy for both lobbyists and policy-makers. It is precisely within the relationship between influencers and policy-makers in the digital context where our analysis is set.

We attempt to establish the relations between think-tanks that are generated by their Twitter networks. Twitter provides us with the ability to generate a representative ‘picture¡ of the interests and relationships of think tanks as a defining attribute of political influence, which we find to be much more interesting in contrast to the network’s own activity.

The global relations of think tanks

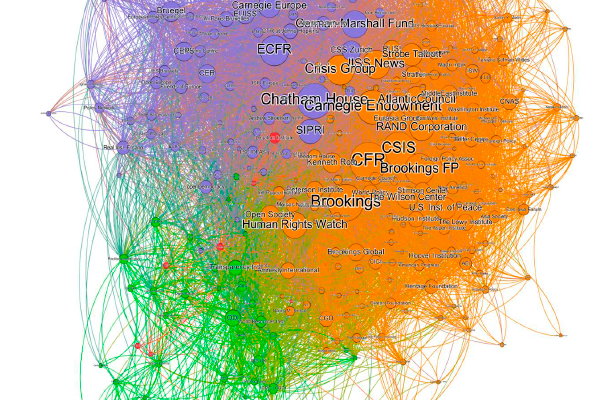

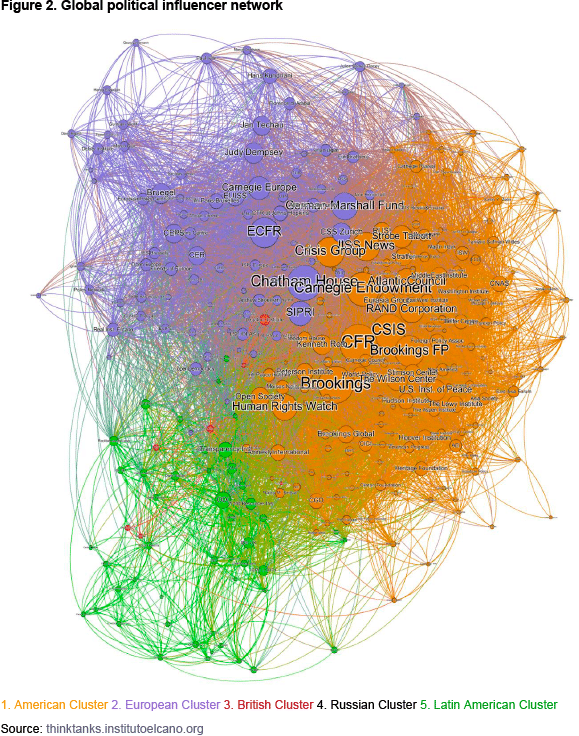

For the third consecutive year, the Elcano Royal Institute is introducing an analysis of political influencer relations on Twitter, which includes the most active think tanks and their associated active researchers on the social network. We have gathered a total of 695 twitter channels that include analysts and information centres that shape a small but influential network within international politics and diverse research areas in international relations.

Our representation of the influencers’ network shows the degree of popularity that each Twitter channel –be it think tank or associated researcher– has with its network of trendsetters and opinion leaders. This is represented by the size of its node (a point in a network topology in which lines intersect), where a bigger node will indicate a higher degree of popularity within the network.

As mentioned above, our interests is in understanding the way in which think tanks achieve political influence with policy-makers. For this purpose –in the way we have suggested in 2015, along with Juan Pizarro and Juan Luis Manfredi in their structural analysis of the influence of think-tank networks in the digital era–, we need to understand the existing relationships between think tanks themselves and their relationships with the three most important international political hubs –Washington, London and Brussels–, including the goals and interests of policy-makers in each of these hubs. It is important to note that due to the gaps in Twitter use (such as its prohibition in China or the use of non-English languages), we have not identified any meaningful political Asian hub within our network.

With the goal of identifying existing relations between think tanks (and their associated researchers) we have simplified the political influence network established in 2017. By measuring network modularity we have identified five sub-clusters. We understand modularity as the ability of a network to be seen as a union of several modules, sub-networks, clusters or communities that interact with each other and shape a common logic within the global network. Each module has elements that characterise it in comparison to other modules while maintaining its relation to the global network.

Thus, we have identified three clusters that we consider think tank groups, which are very similar to previous years because they revolve around the London, Brussels and Washington political hubs. A fourth cluster is articulated around Moscow as an emergent political hub, and the fifth identified cluster is an amalgam of Latin-American states that communicate mainly in the Spanish language, together with an amalgam of European, African, Asian and Middle Eastern actors that deal with economic development and environmental issues.

Brussels and Washington: the dominant hubs

In 2017 Brussels has not overcome Washington as the dominant hub but it has recorded an 11% rise and is 12% more active than in 2016.

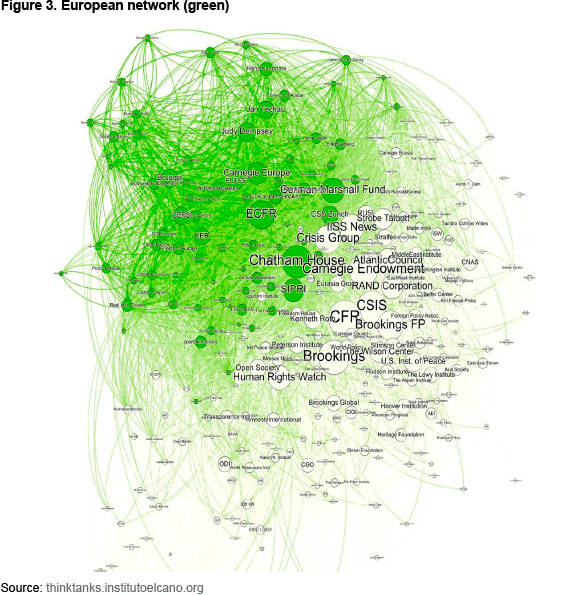

Europe is more present than in previous years; however, Washington has not reduced its centrality within the network nor its influence over think tanks from East Asia and the Pacific.

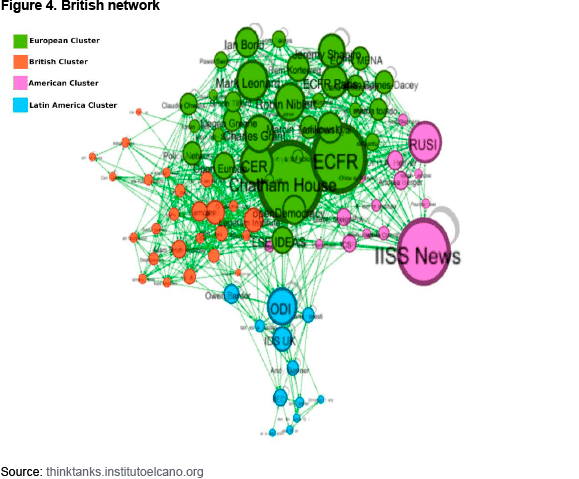

Brussels has more power of attraction than London within our influencer network and the British cluster is found to be diminished in favour of the European cluster. Many British think tanks acquire European elements. This does not necessarily mean that they are becoming more European, rather, they are establishing more connections with continental sub-networks while their analysts promote their relationships within European environments.

The European network takes advantage of the impact that Brexit has over British analyst centres in order to broaden its relationship networks. Many of the most influential British think tanks look towards Brussels in an attempt to unravel possible future scenarios in regards to Britain’s exit from the EU.

The interests of London as a political hub lie within trade, international economy and development, which makes the London hub a bridge for the flow of ideas between Latin America, Europe, the US and some parts of Asia. Brexit is causing this nexus to weaken and many think tanks are starting to shift their relations towards other hubs such as Brussels or the so-called Latin-American cluster. For instance, the European Council of Foreign Relations (ECFR) is considering moving its offices out of London given its perception that the city is ceasing to be a central pivot in European foreign and security policy.

The British cluster becomes more homogenised and specialises in public policy with a focus on economics. In any case, London still prevails as the structural nexus of influence in global topics such as development, climate change policy and economic globalisation. At the same time, rather than fading, part of the London hub looks towards Europe with less of an intention to politically influence an ever more polarised European network, but rather to understand the different existing perspectives on Brexit and the future of the EU.

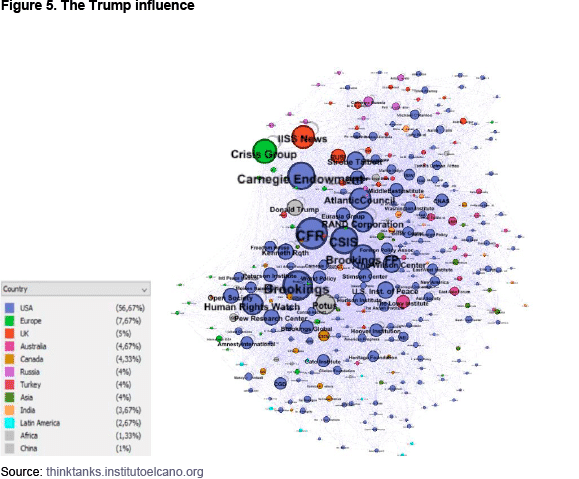

The North-American cluster, which revolves around Washington and specialises in global security issues, is reducing its size possibly due to the indifference of President Trump’s Administration to influencer networks. The North-American module includes some British, Turkish, Australian, Canadian and European think tanks which are devoted to the analysis of international security and geo-politics. It is a network that is mainly categorised by classical topics within international relation studies, but it also includes some think tanks with an interest in public policy and local politics.

In Figure 5 the grey dots represent Donald Trump’s twitter channels @potus and @TheRealDonaldTrump. Trump’s victory and his particular vision of what some have classified as a new form of public diplomacy has caused a certain indifference among the participants of our influence network. These presidential twitter channels are disassociating themselves from the rest of the network, which is reducing its interactions with the effective power in Washington.

With this ‘new digital public diplomacy’, the Trump Administration seems to be refraining from validating any type of political influence originating from external actors, at least for the time being.

The so-called ‘Latin-American cluster’ switches its focus and grows due to the increase in network modularity. It can be inferred that the interest in Latin American issues is growing but, on the other hand, is being subsumed in a sub-network where the Spanish language and Latin-American characteristics lose weight in favour of global issues and international economics.

Influence according to Moscow

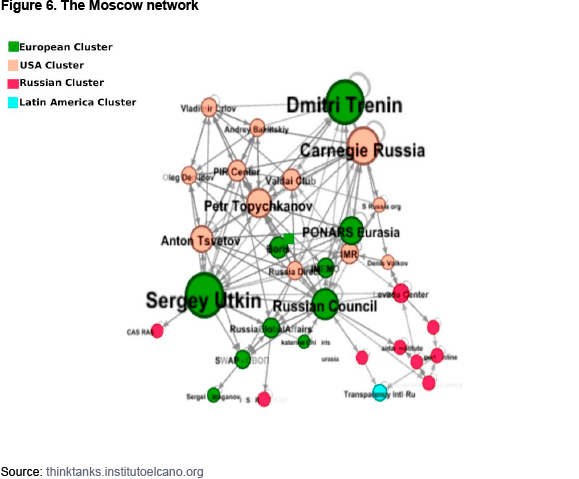

The Russian module is the big novelty in the Think Tank network in 2017. Absent in previous years, this emerging and still small cluster mainly communicates in Russian and works with areas related to Russian public policy.

While in 2016 most Russian think tanks and analysts had strong connections within the European network, in 2017 there are divergent elements that suggest that Moscow intends to enclose itself in order to protect its policy discussion from foreign influences.

First, as regards the influencer network of 2016, it can be seen that a significant number of Russian think tanks have considerably reduced their Twitter activity while still maintaining their relationship networks.

Several important nodes, such as CPEI and fom_media, completely ceased their networking activities in late 2015 and early 2016 and furthermore it can be seen that all nodes within the Russian cluster are think tanks or institutions rather than individual journalists or researchers, while at least 50% of Russian nodes belonging to the European cluster are individual, non-institutional accounts. It seems, therefore, that there is some political influence on what sort of information is generated officially through Russian information centres, while individual journalists are able to maintain some sort of independence in their behaviour within the network.

Additionally, it is important to note that only one third of Russian nodes have been grouped into what we identify as the Russian cluster according to its modularity factor, with the other two-thirds spread evenly between the European and North American clusters.

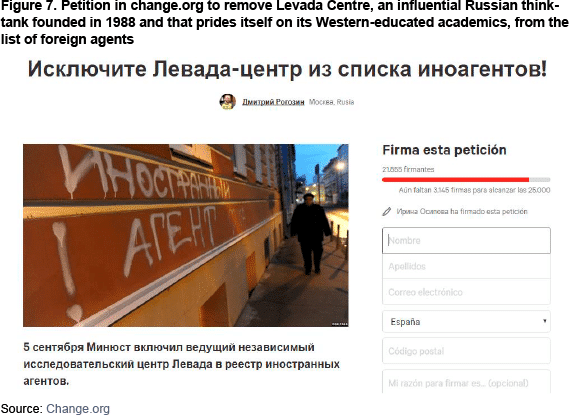

For instance, in 2016, 20 out of 165 European nodes were of Russian provenance. This year, however, only 10 out of 238 European nodes were of Russian origin. This shows that the nodes in the new Russian cluster according to the network’s modularity factor are gradually distancing themselves from previously stronger ties with European and North-American sub-networks (see Figure 7 above). The Russian Council –a think tank specialising in geopolitics– is the main, and almost the only, intermediary between think tanks in the Russian cluster and the rest of the world; Sergey Utkin is the main Russian influencer despite being part of the European cluster.

There are common topics such as Trump, international relations, military concerns and geopolitics among Russian think tanks; those within the European cluster focus more on EU politics (such as the recent elections in European states) from an international-relations perspective while those in the North American cluster prioritise Russia-US relations. The key particularity of Twitter accounts in the Russian cluster seems to be its propensity to generate articles about foreign influence in Russia from a geopolitical and economic perspective.

Altogether, publications in the Russian language, governmental pressure on supposed foreign agents, the difference in chosen topics noted between Russian nodes inside and outside the Russian cluster seem to be an important factor in strengthening the relationship of these nodes within the Russian cluster and weakening its links with the rest of the network.

Conclusions

Recent political phenomena such as Brexit, the Trump Administration and the latest Russian political practices have given rise to changes in the global influence network over the past year.

Brexit has directed the focus on Brussels, as everyone looks towards it in order to understand such a complex political process, and the Trump Administration has so far ignored the political influence of previously common channels.

Meanwhile, the Moscow cluster, with its isolationist policies, has isolated itself from foreign influences. This has led the network to polarise, as political interest in Washington, London and Moscow has become more localised, concentrating more on public policy. Furthermore, the network has also become simplified, as clusters establish fewer relationships between each other and more within themselves.

The size and influence of clusters also varies, as Brussels is growing, to the detriment of Washington and London. Moreover, Brexit and the Trump Administration’s obstacles to free trade generate unrest in traditional networks of influencers thereby inducing a shift in their relationships; Trump, Brexit and Russian isolationist policies promote the growth of the European network because they reduce their own global influence by dealing mostly with internal issues. The Brussels cluster, on its part, is deemed the most stable as it seems to be maintaining the status quo in this regard.

To conclude, we have observed that Brussels has gained popularity within our global influence network, leading us to believe that 2017 might be the year in which Europe will have the opportunity to position itself at the forefront of many aspects of global political activity such as climate change, support for democratisation processes, human rights and international trade.

Juan Antonio Sánchez Giménez

Head of Information Services, Elcano Royal Institute | @Elcano_Juan

Evgueni Tchubykalo

CAMRI doctoral researcher in media and communication, University of Westminster | @chubykalo