Theme

The 29th Conference of the Parties (COP29) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) will be held in Baku, Azerbaijan, from 11 to 22 November. The negotiations to determine a new climate finance goal are expected to be at the heart of difficult discussions.

Summary

COP29, known as the ‘finance COP’, being held in Baku, Azerbaijan, is likely to face significant challenges in achieving an ambitious outcome. This is so given the current geopolitical context, the diminishing appetite for climate policies and despite 2024 expected to be the hottest year on record, while extreme weather events are increasingly destructive. The recent re-election of Donald Trump in the US and the potential implications of its third ‘climate default’ raise concerns regarding the future of climate negotiations. However, this is not expected to significantly affect the climate ambitions of the EU and China. In this context, the EU will have an opportunity to strengthen its role as a bridge-builder to foster greater ambition by enhancing partnerships with regions such as Latin America and the Mediterranean.

COP29 will build on the results of COP28. This will mean striving to implement the UAE consensus that included the goal of transitioning away from fossil fuels in a just manner, trebling renewables and doubling energy efficiency by 2030, among others. Some of the key elements on the negotiation agenda for COP29 include: reaching an agreement on the climate finance goal, known as the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG), which could be a key enabler of Paris-aligned climate commitments to be submitted by Parties by 2025 (called Nationally Determined Contributions, NDCs); finalising the rules for carbon markets under article 6 of the Paris Agreement; the operationalisation of the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD), including enabling access to the fund for less developed countries and enhancing commitments made to the FRLD; and the development of metrics for measuring progress on the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA). Additionally, the timely submission of NDCs, National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) and Biennial Transparency Reports (BTRs) will be essential to enhance ambition, transparency and accountability across all pillars of the Paris Agreement.

The COP29 Presidential Action Agenda, which brings together Party and non-Party stakeholders outside the negotiations, includes various voluntary financial and coordination initiatives that are relevant for large greenhouse-gas emitters and for developing countries. Among these initiatives it will be interesting to follow the support for and commitments made to the Climate Finance Action Fund (CFAF), among others. The CFAF is expected to be capitalised with voluntary contributions of fossil-fuel producing countries and companies and will allocate three-quarters of its funding to supporting the development of NDCs and to addressing Losses and Damages suffered by less developed countries.

Analysis

1. The context

With 2024 anticipated to be the hottest year on record for the second consecutive time, extreme weather events have intensified worldwide. From devastating floods in Spain and the Sahara, to record-breaking fires in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest and extreme heatwaves and droughts, these climate impacts are exacerbating insecurity.

At the same time, political divides run deep. Over 50% of the global adult population has gone to the polls in 2024 (eg, the US, Mexico, India, Brazil and the EU, among others). For some political parties in these countries, climate change is not prioritised –or not even considered politically relevant– and multilateralism is being challenged. This situation creates political uncertainty with potential consequences beyond national borders and across many of the UNFCCC donor countries.

The 29th Conference of the Parties (COP29) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) will take place against unprecedented global turbulence and major recent events including the US elections. The election of Donald Trump is a setback for international climate negotiations, as he will seek to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. A further withdrawal from the UNFCCC has been considered by the Trump team, although it is likely to be less straightforward. Until the US withdraws from both climate treaties, the US negotiating team will continue to participate in climate talks. Under Trump, commitments to international climate finance will most likely continue to fall short of being fulfilled. To counteract the US vacuum on the international stage, State level initiatives such as ‘We are still in’, presented in 2016 after Trump was first elected President, could emerge.

Trump’s return may weaken climate ambition ahead of COP30, particularly affecting the achievement of a renewed climate finance goal at COP29 (the New Collective Quantified Goal, NCQG), which would in turn dampen the prospects of ambitious climate commitments (Nationally Determined Contributions, NDCs), especially from debt-ridden and international climate-finance dependent developing countries. Within US borders, recently adopted legislation like the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) are expected to stay in place as Republican-led states have greatly benefited from them, albeit with parts of them being ‘targeted’ by Trump. However, the pace of investment in renewables might slow down and unspent funds may be rescinded. Delays in permits or grid connections could also occur. Experts have ruled out a significant revival of coal, citing the lack of success in Trump’s first term.

The US’s third climate default (after signing and not ratifying the Kyoto Protocol and withdrawing from the Paris Agreement in 2020), however, is not expected to significantly alter the climate ambitions of the EU and China. The European Commission’s President, Ursula von der Leyen, is urging the EU to retain its historical leadership role in international climate negotiations, using the European Green Deal and the shift towards clean industrial competitiveness, in line with the Draghi report, as ‘guiding stars’. In the current context the EU will have an opportunity to strengthen its role as a bridge-builder, strengthening partnerships with regions such as Latin America, especially in the light of the New Agenda for Relations between the EU and Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as the Mediterranean region, with the designation of an EU Commissioner for the Mediterranean. However, a limited EU presence at COP29 –due to institutional changes, coupled with ongoing hearings– may limit its clout, despite being the largest international climate finance contributor, providing €28.5 billion in 2022 (under a third of the US$100 billion objective).

Given the complex context in which negotiations will take place, this analysis presents some of the key issues that will be negotiated at COP29 as well as the positions of developed and developing countries in addition to some of the most salient initiatives of the Presidential Action Agenda.

2. What to expect from COP29

International climate negotiations can be structured around four main pillars: (a) mitigation (ie, reducing greenhouse gas emissions); (b) adaptation (to the impacts caused by climate change); (c) losses and damages (ie, impacts that cannot be avoided given mitigation actions and adaptation limits); and (d) means of implementation (which include financial and technology transfers, capacity building, etc). Each year the Presidency of the COP establishes its priorities within the elements that need to be negotiated under the climate treaties. In addition, the COP Presidency supports initiatives that bring Party and non-Party stakeholders together under the Global Climate (or Presidential) Action Agenda. The following section analyses the COP Presidency’s Priorities regarding both the UN-negotiated items and its Presidential Agenda.

2.1. Some key issues in climate negotiations

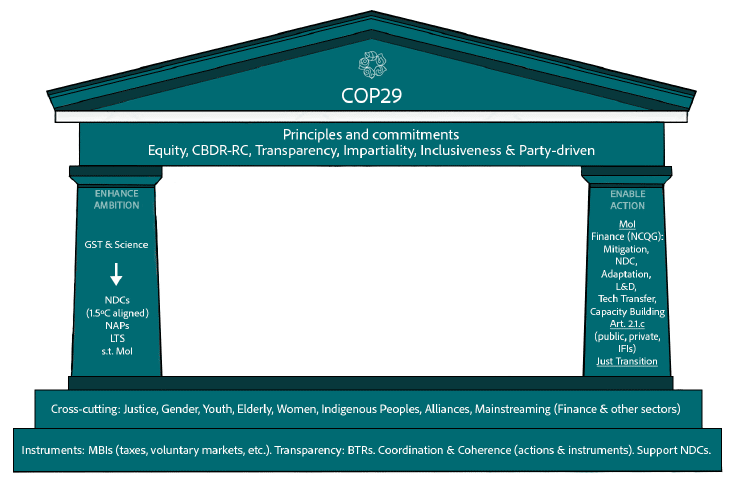

The Azerbaijani Presidency of COP29 has outlined two key elements for this year’s summit: enabling action and enhancing ambition (depicted inFigure 1 and explained below).

Figure 1. The COP29 Presidency’s priorities

2.1.1. Climate finance: the gordian knot at COP29

Climate finance has been a substantive issue at international climate negotiations since 1992. COP15 in 2009 marked a turning point in climate finance negotiations as both the Fast-Start-Finance (US$30 billion between 2010 and 2012) and the US$100 billion annual commitment were agreed on to mobilise resources to support the mitigation and adaptation actions of developing countries. These commitments were reflected in the Cancún Agreements of 2010.

In 2024 the current climate finance goal should be updated, becoming the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG), with US$100 billion as a floor. Negotiations over the past three years on the successor of the US$100 billion goal, the NCQG, have resulted in limited progress. The fact that the OECD confirmed the US$100 billion commitment was met in 2022 (with international climate finance reaching US$115.9 billion that year), two years after the 2020 deadline, does not bode well for the upcoming negotiations.

One option for the structure of the NCQG could be a ‘layered’ climate finance goal, which has been supported by developed countries. It would include an inner layer reflecting climate finance commitments by the public sector and funds mobilised by the public sector, which developing countries have stated should be disbursed primarily in the form of grants from developed countries and earmarked to a significant extent for adaptation given the difficulty in funding adaptation projects. An outer layer would include other private contributions to climate finance and, more broadly, the alignment of financial flows with climate goals. Developing countries are nonetheless calling for a unique climate goal that can respond to their needs and that is counted on a grant-equivalent basis.

There are many issues that have been debated and that remain unresolved as regards the NCQG, as described in Figure 2 below. The issues are: the amount (more frequently referred to as the quantum) of climate finance; the expansion of the donor base; how to determine the recipients of finance; the timeline of finance commitments; and future (upward) revisions of the finance goals to address the changing needs of developing countries, among others. The scale of climate finance needed according to the 142 Parties’ NDCs –which does not cover all needs– is substantial, with global analyses signalling that trillion(s)[1] will be needed annually if developing countries are to be able to mitigate and address the full set of impacts of climate change (eg, the UNFCCC First Report on the Determination of the Needs of Developing Country Parties, known as NDR 1, and the UNCTAD’s latest Trade and Development Report). On an annualised basis, current NDC requirements of a subset of the 142 NDCs analysed on climate finance would range between US$455 billion and US$584 billion per year, between 4.5 and 5.8 times the current amount. According to developed countries, whether they can mobilise such an amount is uncertain as their public budgets are currently overstretched. Developing countries argue, however, that the problem is not the lack of funds but the limited political will to allocate available funds to climate finance.

Figure 2. Issues to watch during NCQG negotiations at COP29

| • The purpose. Developed countries advocate that the NCQG should contribute to advancing the alignment of all financial flows with climate goals as per Article 2.1.c of the Paris Agreement. Developing countries on the other hand call for the NCQG to respond to Article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement, which states that developed countries should provide finance to developing countries for their mitigation and adaptation actions. As for where finance should be allocated, Africa’s priority would be adaptation. Least Developed Countries call for the inclusion of Loss and Damage in the NCQG. • The amount (quantum). Developed countries have not proposed a specific amount for the NCQG. Some of them indicate that without broadening the contributor base, scaling up the current US$100 billion per year will be difficult. It also remains to be seen what sources of finance and what instruments developed countries include in the new quantum. Developing countries say their funding needs, estimated in the trillions, must be met. Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDC), the Arab Group and the African group have proposed targets ranging from US$1 trillion to US$1.3 trillion, which would require approximately a 10-fold increase in current climate finance. • Who should contribute. Referring to article 9.2 of the Paris Agreement, developed countries propose broadening the contributor base to those emerging economies that are in a position to contribute to the international climate finance target, ie, China and the Gulf States. Some of the criteria proposed for broadening the contributor base are GDP, greenhouse gas emissions, being a member of the OECD and the G20, among other criteria. Developing countries, relying on the principle of the common but differentiated responsibilities of the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement (and also in line with Article 9.1) reiterate their view that it is developed countries that should provide financial resources to developing countries for their mitigation and adaptation actions. • Sources of finance. Developed countries indicate that public resources are insufficient to meet the needs of countries and suggest that the quantified target should be multi-layered, including a significant component of private investment. Developing countries suggest that the NCQG should be based on the provision of public funds in accordance with the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR-RC), with a greater weight of grants and concessional loans. • Qualitative elements of the NCQG. Both developed and developing countries support integrating qualitative elements into the financing goal. Developing countries demand faster and simpler access, especially for countries that are more vulnerable to climate change. • Timeframe and updating of the NCQG. There are divergent views on the duration and review of the NCQG. Proposals include a five- or 10-year timeframe for the NCQG and there are proposals both to revise the NCQG and not to revise it. For developing countries, the changing needs arising from climate change and policies to address it mean that the funding target should be updated (revised upwards), with some countries indicating that such a review should take place every five years. |

2.1.2. Enhanced ambition

The COP29 Presidency aims to encourage all countries to submit more ambitious NDCs by February 2025. The summit will be a key moment for Parties who submit their NDCs early to set a high standard, with updated 2030 targets and new 2035 ones. The Troika of COP Presidencies (UAE-Azerbaijan-Brazil) has launched the ‘roadmap to mission 1.5ºC’, committing each Party to submit their NDCs aligned with the goal of limiting the global temperature increase to 1.5ºC above pre-industrial levels (NDC 3.0º-1.5ºC). To meet this goal, NDCs must include a commitment to transition away from fossil fuels and contribute to trebling renewable energy capacity and doubling energy efficiency by 2030. Just before COP29, the UAE was the first to submit its updated ‘NDCs 3.0’, which the country claims is 1.5ºC-compatible.

In parallel, the Troika will cooperate with key thematic and political platforms, including collaboration networks (alliances), another element to raise ambition. Aware of the challenge ahead and the limited progress made in the Bonn intersessional meetings in June 2024 (SB60), the COP29 Presidency has repeatedly highlighted alliances, support and pre-summit meetings in its communication with the Parties, presenting opportunities for Parties to demonstrate an increased ambition ahead of COP29. The G7 and G20 are highlighted, among others. The importance of strengthening the relationship between the Rio Conventions (climate-biodiversity-desertification) in the context of international environmental agreements is an additional call to action by the Troika of Presidencies.

2.1.3. Committing to Loss and Damage finance & facilitating access

Another essential element to promote action, according to the Azerbaijani Presidency, is the operationalisation of the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD) increasing funding commitments, while also facilitating access to the fund for the most climate-vulnerable countries.

Discussions on Loss and Damage (L&D) have gained traction at climate negotiations in recent years, with the establishment of a new fund at COP28 last year. The World Bank announced it will host the fund on an interim basis and act as a trustee. The fund is on track to disburse its first round of funding by 2025, and the appointment of an Executive Director of the FRLD is expected to be announced soon.

With the fund in place, and attention shifting to the new NCQG, discussions are expected regarding the inclusion of L&D finance in the NCQG, with developed countries arguing that L&D finance is outside the NCQG’s mandate, signalling once again that they do not want to be held liable for the impacts of climate change that countries cannot adapt to.

2.1.4. Adaptation: progress and clarity needed for the UAE-Belém Work Programme

The adaptation finance gap, currently estimated to be between US$194-366 billion per year, highlights the need for increased funding to support global climate adaptation efforts. At COP28 the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience (FGCR) was launched as the culmination of the two-year Glasgow-Sharm el-Sheikh (GlaSS) work programme on the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), providing countries with adaptation and resilience targets. The UAE FGCR needs to include means of implementation –finance, capacity building and technology transfer–. The development of indicators is being made under a two-year UAE-Belém work programme for measuring progress. The practicalities of this programme were meant to be discussed at Bonn (SB60), eg, organisation of work, timeline and involvement of stakeholders. A procedure was established to enhance the mapping of indicators, for instance, through the recruitment of experts and the organisation of dialogues and workshops. The draft conclusions also highlight the critical importance of funding for adaptation, technology transfer and capacity-building. Adaptation negotiations in Bonn also concentrated on National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), with only 50 countries having their NAPs in place. The GGA envisions comprehensive NAP coverage by 2030, yet financial, technical and capacity-building support remain significant challenges that will need to be revisited in upcoming discussions in Baku.

The recent appointment of Ireland and Costa Rica as Ministerial Pairs for Adaptation is a positive development, signalling the intent of the Presidency to strengthen adaptation efforts on the agenda. Key objectives of the COP29 Presidency appointments are to ‘help enhance understanding on current priorities and perspectives, identify possible opportunities and barriers, and facilitate progress on substance’.

The Report on Doubling Adaptation Finance highlights a joint commitment made at COP28 by four multilateral climate funds –the Adaptation Fund, Climate Investment Funds, the Global Environmental Facility and the Green Climate Fund– ‘to strengthen the complementarity and coherence among funds and move toward harmonising procedures’. Broadening access remains essential to scaling up adaptation finance. The above-mentioned commitment, which will be formalised as an action plan at COP29, is a significant step towards closing the adaptation finance gap, by simplifying processes to improve accessibility and building capacity to attract both public and private investment.

These steps are vital to close the adaptation finance gap, strengthen resilience and ensure that countries are equipped to adapt to the escalating impacts of climate change.

2.1.5. Strengthening carbon markets

There are two forms of carbon trading under the UN system in the COP29 agenda: direct country-to-country trading (ITMOs) under Article 6.2; and a centralised international carbon market under Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement. Negotiations on Articles 6.2. and 6.4. at COP28 last year concluded without an agreement, with unresolved issues such as credit authorisation, transparency and problem identification through review processes. At the SB60 in Bonn, the Azerbaijani Presidency emphasised that these technical issues would be a priority for COP29, which came as a surprise to many observers since the country has not previously engaged substantively with this agenda item.

Some progress has been made since June 2024. In October 2024, ‘article 6.4 Supervisory Body’ of what is known as the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism (PACM) approved the standards for operationalising cooperation between Parties via projects (the successor to the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism), although at COP29 Parties could reject or request changes to these standards. A Sustainable Development Tool was approved with environmental and social safeguards that project developers will have to take into account, with external supervision and ensuring the inclusion of the communities where the projects are developed. In addition, there will be a review of the Sustainable Development Tool every 18 months and developers will be required to indicate how projects contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals. The standards will apply to both new projects and projects transferred from the Clean Development Mechanism.

2.1.6. Transparency, partnerships and the role of financial institutions and the private sector

Biennial Transparency Reports (BTRs) are considered by the COP29 Presidency to be key to obtaining information on Parties’ needs and to building trust between developed and developing countries. Azerbaijan is also working on its BTR, will launch the Baku Global Transparency Platform and has appointed a COP29 high-level pair for transparency, Zulfiya Zuleimenova from Kazakhstan and Francesco Corvaro from Italy.

An additional element to raise ambition is the use of collaborative networks (partnerships). Aware of the challenge ahead and the modest progress at the inter-sessional meetings in Bonn in June 2024 (SB60), the COP29 Presidency repeatedly mentions in its communications to Parties the partnerships, support and meetings in the run-up to Baku, as well as other meetings where Parties can show their increased ambition, the G7 and G20. As regards International Environmental Agreements (IEAs), the Presidency calls for strengthening the relationship between the Rio Conventions (climate-biodiversity-desertification).

Finally, the role of international financial institutions (IFIs) is once again highlighted as essential to align financial flows and climate goals by the COP29 Presidency. The private sector and Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) are also recognised as central to the process of transforming the development model, with specific initiatives designed to help them share best practices.

Figure 3. Summary key issues in negotiations

| Negotiation topic | Summary |

|---|---|

| Climate finance | The NCQG aims to establish a new climate finance target beyond the current US$100 billion. Developed countries support a layered finance goal, while developing nations call for a unique, grant-focused goal. Issues that remain unresolved include the purpose, the quantum, the contributor base, the founding sources, qualitative elements and the timeline for updates. |

| Enhanced ambition | The COP29 Presidency is pushing for ambitious NDC submissions by 2025, with new targets for 2030 and 2035. The Troika’s ‘Roadmap to Mission 1.5ºC’ will strive to implement the UAE Consensus and support Parties in raising ambition ahead of NDC submission. The importance of reinforcing cooperation between climate, biodiversity and desertification frameworks is also emphasised to create an additional call to action in the context of international environmental agreements. |

| Loss & Damage (L&D) | Discussions on operationalising the FRLD focus on increasing funding commitments and facilitating access for vulnerable countries. The L&D fund, hosted by the World Bank, is expected to start disbursing funds by 2025. Debates continue on whether L&D finance should be included in the NCQG. |

| Adaptation | The work on adaptation will focus mainly on developing indicators to measure progress on GGA. This includes setting targets for resilience and adaptation and enhancing the coverage of NAPs by 2030. The recent appointment of Ministerial Pairs for Adaptation signals a push for greater importance of adaptation on the agenda. Moreover, the commitment made by four climate funds at COP28 to improve complementarity, accessibility and attract public and private investment is expected to be formalised into an action plan at COP29. |

| Carbon markets | Discussions on Article 6.2 (country-to-country trading) and 6.4 (centralised international market) of the Paris Agreement continue, with the Azerbaijani Presidency prioritising this point of the agenda. A Sustainable Development Tool has been approved by the Supervisory Body of article 6.4 to ensure environmental and social standards in projects, which requires environmental and social safeguards, periodic reviews and alignment with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). |

| Transparency and Financial Institutions | Biennial Transparency Reports (BTRs) are considered by the COP29 Presidency to be essential to build trust and report needs among Parties. Baku Global Transparency Platform aims to support developing countries in meeting Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF) standards and digitalising climate reporting. Additionally, financial institutions and the private sector are urged to align financial flows with climate goals. |

2.2. Salient elements of the COP29 Presidency’s Action Agenda

This subsection presents an overview of five initiatives put forth in the COP29 Presidency Action Agenda (Global Climate Action Agenda). They address finance and investment, human development, agriculture and transparency. Each initiative is designed to foster cooperation, enhance resilience and drive sustainable development, aligned with climate objectives. Figure 4 summarises the objectives and anticipated outcomes of these initiatives.

Figure 4. Initiatives highlighted in the COP29 Presidency’s Action Agenda

| Initiative | Objective | Key outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Climate Finance Action Fund (CFAF) | Increase climate finance by creating a fund that is capitalised with voluntary contributions of fossil fuel countries and companies | (a) Invest in climate projects, support R&D, and grant assistance for Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and Less Developed Countries (LDCs). (b) Establish a US$1 billion fund requiring pledges from at least 10 countries. (c) Focus on income-generating investments in developing countries, emphasising renewable energy and green job creation. (d) Allocate 20% of fund income to a Rapid Response Facility (2R2F) for concessional and grant-based disaster assistance for SIDS and LDCs. (e) Allocate 50% of the contributions to support more ambitious NDCs. (f) Deploy diverse financial instruments (green bonds, venture capital, equity) to support low-carbon projects. (g) Include an independent audit committee and a Board of Directors to ensure transparency and good governance. |

| Baku Initiative for Climate Finance, Investment and Trade (BICFIT) | Reinforcing the role of climate finance, investment, and trade in addressing challenges of climate change and sustainable development | The BICFIT dialogue seeks to: (a) Enhance coherence between the climate finance, investment, trade and sustainable development agendas and policies. (b) Facilitate platforms for cooperation among international organisations, Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), climate funds, the private sector, civil society and academia. (c) Support the design of bankable climate-related projects that can be implemented at the local level. (d) Encourage Climate Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) by supporting developing countries finding market opportunities (eg, through new initiatives like Green Free Economic Zones (GFEZs) and blended finance solutions to increase private-sector engagement in climate finance. (e) Promote green growth among SMEs, including the Baku Climate Coalition for SME’s green transition. (f) Promote knowledge-sharing on aligning investments with climate goals, maximising synergies between climate action and SDGs. (g) Host the BICFIT Dialogue Conference. |

| Baku Initiative on Human Development for Climate Resilience | Integrate health, education, and social protection into climate action, with a focus on vulnerable groups | (a) A High-Level Meeting hosted by the COP29 Presidency, giving a holistic approach of climate resilience and sustainable development in different areas (eg, health, education, green jobs, skills development). (b) The announcement of the Joint Statement on Baku Initiative on Human Development for Climate Resilience among UN agencies, MDBs and Multilateral Climate Funds (MCFs). (c) The adoption of Baku Guiding Principles on Human Development for Climate Resilience. (d) Promoting international cooperation on greening education, enhancing environmental literacy and resilient infrastructure in education. (e) Establish a COP continuity coalition on climate and health to ensure ongoing health considerations in climate action, in partnership with World Health Organisation (WHO). |

| Baku Harmoniya Climate Initiative for Farmers | Empower farmers and rural communities by clarifying the landscape of initiatives, coalitions, networks and partnerships, and fostering collaboration | (a) Create a platform to clarify existing initiatives to foster knowledge exchange and enhance collaboration. (b) Catalysing investments in agri-food transformation and aligning efforts with MDBs and Agricultural Public Development Banks (PDBs). (c) Empowering marginalised farmers, including women and youth. |

| Baku Global Climate Transparency Platform (BTP) | Enhance transparency and trust in climate action, supporting countries in meeting the Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF) | (a) Host workshops and capacity-building events for developing countries to submit their BTRs. (b) Promote experience-sharing among Parties to build confidence and capacity in climate reporting. (c) Organise a Ministerial Meeting on Global Climate Transparency at COP29 to reinforce commitment to transparency and accountability. (d) Support digitalisation and innovation in transparency reporting to streamline climate data tracking and submission. |

Conclusions

COP29 in Baku is expected to be fraught with difficulties. The global geopolitical context, the recent election of Donald Trump and electoral results in various countries that do not support (or are contrary to) an ambitious climate agenda, coupled with a two-year delay in meeting international climate finance commitments could limit the results of negotiations on the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG). Limited high-level representation from large greenhouse-gas emitters and climate leaders at COP29 is telling of the expectations for this COP.

A lack of ambition in the new finance goal would in turn imperil the presentation of 1.5ºC-aligned climate commitments (Nationally Determined Contributions, NDCs) ahead of COP30. The developing countries’ climate ambitions are heavily dependent on international climate finance. The commitments to increase climate finance from 2025 onwards present an opportunity for the EU, as the largest contributor to international climate finance, to play a significant role. While this COP might be seen as a transition climate summit by some, a credible, confidence building and robust result in Baku is a precondition for a Paris-compatible COP30.

The main topics of COP29 –climate finance, ambition in NDCs, just transition, adaptation and L&D– are all crucial elements of limiting temperature increases as close to 1.5ºC as possible. The Troika’s ‘Roadmap to Mission 1.5ºC’ emphasises the collective ambition needed, with early NDC submissions potentially setting an example. However, limited progress during Bonn’s intersessional meetings has tempered expectations.

[1] Please note: 1 trillion = 1012.