An Introduction to French Strategic Culture

France is one of the EU member states with a most highly-developed national strategic culture. Victory in the Second World War, its role as a member of the United Nations Security Council, the development of a nuclear programme that gave the country the status of a nuclear power, united to the historical development of a sense of a global mission on the world stage, contributed to the development of a global vision for France’s role on the world arena. The exercise of setting out a global description of a long-term vision and strategy for defence policies in white books (Livre Blanc) had been conducted twice before, in 1972 and 1994. The latest 2008 White Paper on Defence and National Security preserves some of the basic patterns of its forerunners but introduced the concept of a national security strategy, that had not been developed before.

The ordinance of 7 January 1959, which dealt for the first time with the general organisation of defence, provided the first national definition of ‘defence’ as the instrument ‘to ensure at all times, under any circumstances, and against any form of aggression, the security and the integrity of the territory as well as the life of the population’.[1] Consequently, by 1959, the French definition of defence included the aspect of constancy of action (defence of the territory at any time, in war as well as in peace) and of global action (ie, including all military and non-military aspects of the protection of the nation against aggression). This order was largely influenced by the political context of that time, with the return of General De Gaulle to power in 1958.

With the arrival of Georges Pompidou to the Presidency of the French Republic, and with the different strategic context of the time, the French authorities issued their first global statement of a national defence strategy with the Livre Blanc de la Défense Nationale in 1972. This document, a milestone for French National Defence, was obviously strongly influenced by the cold war atmosphere. The main issue described in the paper was the national approach to the country’s nuclear deterrence policy. Between the ordinance of 1959 and 1972 France developed its nuclear programme. Consequently, after the departure of Général De Gaulle, France’s national authorities felt the need of drafting a national doctrine for the use of nuclear weapons, the core of the 1972 White Paper.

A new French White Paper on National Defence was issued in 1994. If the 1972 White Paper was defined by ‘nuclear deterrence’, the 1994 version was defined by the concept of the ‘projection’ of French forces abroad for peace-keeping missions. The 1994 paper was characterised by a post Cold War approach. The emphasis was on ‘new threats’ and regional conflicts, while the possibility of a major conflict on French soil started being considered unlikely. The Gulf War of 1991 and the crises of the 1990s in the Balkans made it clear that the post Cold War world seemed to be characterised by the emergence of local conflicts but with potentially damaging effects on French national interests. During the preparation of the 1994 White Paper the idea of including internal security issues within the National Defence Strategy was debated for the first time. Although the idea was finally rejected, the 1994 White Paper stated the existence of increasing vulnerabilities due to a diversification of risks and the rise of uncertainty and explained that internal and external security were becoming increasingly linked to each other. Nevertheless, the idea of a security continuum was not acknowledged and the core of the document focused on external threats.

After the election of Nicolas Sarkozy as the new French President, it was decided that a new strategic document was needed, taking into account the post 9/11 events, but also that it was necessary to develop a European security and defence policy. A ‘White Paper Commission’ was created in August 2007, entrusted with drafting the new White Paper, and focused its discussions on the expansion of the security spectrum, culminating in the notion of national security. The Commission was established and presided over by Jean Claude Mallet, former General Secretary for National Defence, and placed under the authority of the Prime Minister. The Commission’s consultations for the preparation of the White Paper were open to the public. More than 250,000 Internet users were consulted, as well as 52 personalities: seven ‘field actors’, seven political party representatives, 10 representatives from civil society (sociologists, ‘representatives from the large religious groups’, journalists and NGOs), and over 20 European representatives from 14 different nationalities. As a result, ‘security’ was taken into account in the White Paper on Defence and National Security published on 17 June 2008 (hereafter the 2008 White Paper).[2]

The document comes after 9/11 and responds to the strategic challenges and the new threats from globalisation, interdependencies and uncertainty. If the 1972 White Paper was the one of nuclear deterrence, and the 1994 one essentially dealt with force projection, the 2008 White Paper stresses the importance of national security, a new concept combining defence and security. The document’s name –‘White Paper on Defence and National Security’– points to a comprehensive strategy to deal with existential threats and risks to the nation in a globalised world. Defence and security are described as a common field in two sections: two separate worlds exist, but they share common interfaces. The border between the two notions is now recognised as a blurred one, hence the need for seamless management across both fields. Strictly speaking, the document contains a traditional defence white paper together with the first formal conceptualisation of a National Security Strategy in France. The strategy reflects the French vision of international security, the role of France in defence and security affairs, French interests to be secured and defended, the available means and the political orientations to guide the development and implementation of the different public policies involved. Given its novelty, the defence elements of the 2008 White Paper involve a greater elaboration than the security ones, though they are now framed under the overarching concept of national security.

More precisely, the French national security strategy aims to deal with ‘all the risks and threats which could endanger the life of the Nation’. In a traditional ‘Westphalian’ way, its first goal is to defend the French population and territory. The second is to contribute to European and international security. The third, more specific to France, is to defend the republican values that bind together the French people and their State: the principles of democracy, including individual and collective freedoms, the respect for human dignity, solidarity and justice. Together with this global approach to the risks and threats affecting the French Nation, the new concept emphasises an integrated approach to security that includes both internal and external security, civil and military means, defence and security forces and, of course, the traditional defence and foreign affairs policies together with internal security policies and the rest of all the governmental policies and instruments of French power.

Finally, the national security strategy presents three basic principles: (1) anticipation-reaction; (2) resilience; and (3) power generation. It also covers five strategic functions: (1) knowledge and anticipation; (2) prevention; (3) deterrence; (4) protection; and (5) intervention. The combination of these principles and functions should allow the adjustment of future white papers to the changing defence and security context through either the approval of the appropriate Military Programs and Interior Security Bills or, if necessary, by changing the 2008 White Paper itself.

Description of the White Book on Defence and National Security

Until the new 2008 White Paper on National Defence and Security was prepared, the French security strategy was essentially based on the existence of the nuclear deterrent, supposed to protect the Nation against any attack on its territory. In this regard, the new White Paper’s ‘revolution’ rests upon the reduction of the deterrence function to the strict minimum within the security strategy. The new White Paper notably asserts that the knowledge of situations, as well as their anticipation, constitute the French State’s first line of defence. In this way, the new White Paper’s innovations are to be sought in the awareness of a mutating international scenario. It implies that the security of France must be increasingly ensured through the stabilisation of remote crises at their earliest stages, something that could not be possible without a steadier multilateral cooperation, either within the EU or the Atlantic Alliance.[3]

More generally speaking, the 2008 White Paper clearly deals with the question of the interconnection of threats, of the continuity between domestic and international security, that are tightly linked, as well as the possible incidence of strategic ‘ruptures’ which might quickly trigger an evolution of the international scenario in which France is involved. Starting from an analysis of globalisation and of the upheavals it has entailed (the decrease of the number of people living under the poverty line, the revolution of communication systems, the reduction of conflicts and so on), the 2008 White Paper also makes reference to strategic uncertainty, insofar as new negatives trends tend to appear. Indeed, it emphasises the downside of globalisation, citing as examples the rapid diffusion of any form of political, economic or financial crisis, simultaneously linked to the intense and immediate transmission of information, making crisis management much more complex. Increasing inequalities are deemed to be threats to the international order. The rising consumption of energy and raw materials has sparked off tensions on energy supplies and global warming. It has also led to the proliferation of all kind of weapons, the development of terrorism, the rise of global military expenses, unsolved crises on the international scenario (notably in the Middle East) and the decline of the Western powers, explained by the shift of the centre of gravity towards the East. Finally, globalisation has tended to weaken the collective security system. All of these changes form part of the strategic uncertainty scenario as outlined by the 2008 White Paper, and might fuel any kind of threat against the country’s security.

Thus, the new French White Paper more particularly points to an ‘arc of crisis’ from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, an area of strategic interest in which any crisis or security threat can have direct implications on the security of French citizens and on the country’s interests. It mentions threats of instability, of violence between institutional actors or non-institutional ones, threats of proliferation of WMDs (Weapons of Mass Destruction) or threats of depletion of energy resource supplies. Within this ‘arc of crisis’, Sub-Saharan Africa, characterised by failed states, runaway urbanisation and the effects of climate change, as well as Eastern Europe, the centre of concern regarding the future of the Balkans and the evolution of Russia, are deemed to be examples of upcoming potential crises. The prospect of a major forthcoming conflict in Southern or Eastern Asia is not excluded either by the White Paper.

(a) National Security’s Strategic Functions

In order to tackle the security and defence threats and risks it identifies, the 2008 White Paper develops five strategic functions: (1) knowledge and anticipation; (2) prevention; (3) nuclear deterrence; (4) protection; and (5) intervention. These functions are multidimensional, for they not only concern the French Defence Policy but the State apparatus as a whole.

Knowledge and anticipation. This strategic function is the 2008 White Paper’s main innovation, insofar as, in a way, it acts as a substitute for nuclear deterrence at the heart of the Nation’s defence and security. By ‘knowledge and anticipation’, the French legislator has intended to set out a series of actions to be implemented by the State. The aim is for the State to prevent crises as well as possible and, if needed, to meet them with adequate solutions, in regard to the current changes in the international system. Indeed, with the end of the Cold War, the proliferation of crises and the emergence of new types of threat and terrorism, a proper adaptation of security and defence systems is required in order to respond to the current ‘post-Westphalian’ world.

- The function ‘knowledge and anticipation’ includes five fields of action: intelligence; a good command of operation stages; diplomacy; prospective analysis aimed at anticipating the development of the international system; and the management of the information that is collected. From an institutional focus, such an important function has led to the creation of a National Intelligence Council, directly headed by the President of the French Republic, and to the appointment of a National Intelligence Coordinator, directly responsible to the President. Furthermore, a series of reforms of the National Intelligence apparatus have been implemented, such as the issuing of a law on intelligence activities, the better protection of secrecy regarding National Defence, a reformed diplomatic network to optimise information exchanges and, finally, a new concept of research centres and prospective agency networks. The reform of careers in Intelligence as well as the recruitment of engineering, computing, image analysis and language experts was also planned to improve the technical capabilities of the Intelligence agencies. More globally, Intelligence activities, and notably human resources and strategic technical material (for instance observation satellites), are promoted through a priority budget line.

Prevention. This strategic function embraces all the other tools deployed by France in order to avoid a crisis beforehand. Thus, the 2008 White Paper sheds light on the synergies of actions from different institutional actors, notably the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Defence Ministry and the Interior Ministry. Among the major innovations promoted by the 2008 White Paper, one should highlight the decision to modify the geography of the defence bases located abroad, notably in Africa: one of the three permanent bases in the continent will be closed. Whilst France’s permanent bases will remain operational in Libreville (Gabon) and Djibouti (not mentioning the non permanent bases in Chad and in the Ivory Coast), the French permanent military base at Dakar will be closed. Regarding this decision, the Dakar base has been officially declared ‘under Senegalese sovereignty’ since 4 April 2010. Besides, a notable innovation concerns the establishment of a French base in Abu Dhabi, following an agreement between France and the United Arab Emirates in January 2008. The deployment of the French army illustrates the shift of the decision-makers’ concerns towards the Middle East, in line with the definition of the ‘arc of crisis’ identified by the 2008 White Paper. Among other prevention policies, the emphasis has been put on criminal trafficking (either within or outside the national and European territories), combating proliferation and controlling armament exports.

Nuclear Deterrence. The third function targets nuclear deterrence. Although the 2008 White Paper somehow underestimates its paramount strategic importance, the proliferation of crises, risks and threats makes demanding a more proactive diplomatic and military action and the nuclear deterrence function an essential feature of the National Defence and Security policy. The New White Paper reasserts that the French nuclear deterrence will remain under national control, and that France is concerned with guaranteeing a total industrial, technological and operational independence regarding its nuclear deterrence policy. The latter will still be funded to cover at least two distinct and complementary vehicles, so as to ensure its durability and their eventual use. Consequently, the 2008 White Paper has confirmed the development of the M51 intercontinental ballistic missile that will be provided to the new generation of SSBN nuclear attack submarines. Likewise, the airborne cruise missiles, such as the ASMP A, are reinforcing the French air deterrence components (the 2000 NK3 Mirages and the Rafales). In order to test the efficiency and precision of the French nuclear warheads and missiles, simulation capacity programmes are being improved, thereby completing the deterrence system. Meanwhile, the 2008 White Paper sets out a French strategy of international disarmament, including the willingness to see the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty universally ratified. This treaty seals the commitment of all nuclear powers to dismantle nuclear sites in a transparent manner, and opens up the negotiations of the Fissile Materials Cut-Off Treaty and other measures.

Protection. The protection function introduces another major change enounced by the 2008 White Paper: the necessity of developing the concept of resilience. This concept indicates, in its present description, the capacity of a nation to reorganise and face an attack perpetrated against its normal functioning. As a result, the French authorities have emphasised in the White Paper that the incidence of an unpredictable terror attack against the national territory, is highly probable; hence, the necessity for the nation to be prepared and to be able to return to normal as soon as possible.

- In order to prevent any kind of risk, the White Paper focuses its analysis on the capabilities gap related to non-conventional threats. In other words, it underlines the necessity to improve French proficiencies in terms of detection, analysis and response to CBRN menaces. Besides, the creation of a top-level political management centre should allow the rapid countering of any major threat through military and civil means. The measures detailed above are completed by a new agency dedicated to cyber-defence, a growing capacity of ballistic missile detection expected by 2020, the modernisation of the public information and alert system, the preparation of a public communications plan in the event of a major crisis, the improvement of operational crisis management at the Interior Ministry as well as at the regional level and, finally, the creation of a 10,000-strong battle group, able to the support civilian authorities if a major disaster occurs. The adoption of such measures reveals the importance attached to the probability of a terror attack through potential non-conventional weapons as the major threat on the national territory.

Intervention. The 2008 White Paper precisely defines the type of military and civilian intervention the French armed forces have to be trained for, as well as the means needed according to the nature of the operation, and carefully justifies the use of military force. Indeed, the latter is conditioned to two main criteria: threats against national or international security and the respect of International Law. The multifaceted dimension of the operations considered shows how the Defence and Security concepts are partially linked. France plans to carry out civil operations to bring humanitarian assistance or civilian help to reconstruction, civilian and military peace-building operations to stabilise a country or peace enforcement operations by the military. Furthermore, France recognises its dependence vis a vis its European and Atlantic allies, acknowledging that only a coalition can lead a major operation. By admitting the importance of the European and NATO frameworks, the 2008 White Paper also defines the French objectives to develop both institutions, and asserts its willingness to ensure international defence and security.

(b) France’s European and Transatlantic Ambitions

National security strategies state what the strategic actors will do by themselves and what they prefer to do with others in a multilateral way. The 2008 White Paper describes the evolution of France’s international strategic position: no major operation can possibly be organised from a strictly national viewpoint. On the other hand, it acknowledges the changing nature of threats and, hence, the need to design new responses. Apart from the key military response, it particularly highlights the necessity of sharing intelligence information and to pool civilian and military resources, in order to counter crises efficiently. In that respect, and despite the notable evolution of France’s position towards NATO through the reintegration of the military command decided by Nicolas Sarkozy in 2009 (which had triggered visible changes in the 2008 White Paper), one is forced to notice France tends to put more emphasis on the EU, deemed the best instrument to counter new threats.

The French Security Strategy makes one feel that while NATO is considered a mutual defence alliance by the French authorities, the EU benefits from a large and varied range of instruments which could make it a key actor in the defence of French strategic security interests. Thus, France asked its European partners to pool military capabilities in order to reduce the shortages that persist at the European level. Such a pooling should include: strategic and tactical transport, in-flight refuelling, mobile-air capability such as helicopters, naval-air capability and the association of aircraft carriers, airbases, on-board air units and the necessary escort carriers.

Apart from the capability issue, the White Paper seeks to encourage the EU to equip itself with a rapid intervention force of 60,000 men, able to remain operational for one year, and to plan and deploy simultaneously two or three civilian peacekeeping or peace enforcement missions. In the same way, the 2008 White Paper has called on the European states to pool their procedures for civilian and military personnel training for this type of operations.

Concerning the armaments industry, the 2008 White Paper calls for the Europeanisation of all the industrial and technological defence bases, due the impossibility for a single European country to master the whole range of technologies needed to ensure a total political strategic autonomy. Nevertheless, some of the existing technologies must imperatively remain under national sovereignty, such as nuclear deterrence, ballistic missiles and information security systems. The White Paper also advocates the Europeanisation of citizen protection, admitting the porosity of borders and the existence of a multidimensional threat. This explains the mention of European cooperation to counter terrorism and organised crime, the idea of creating a European operational centre for Civil Protection and a European College for Civil Security. The White Paper also calls for European states to cooperate in order to counter cyber-warfare, to protect boundaries and to secure supplies.

The 2008 White Paper announced the new role to be played by France inside the Atlantic Alliance. It advocated the full participation of France in the structures of NATO including its reintegration into the integrated military command (normalisation) although it continued to maintain the traditional independence of the French nuclear forces: freedom of assessment, freedom of decision and French command in peace time. As the French National Security Strategy remarks, NATO and the EU are not, to any degree, competitors in the field of defence and security. They complement each other and NATO should evolve so as to take into account new security risks, define a better share of responsibilities between the US and its European allies and, above all, the relations between NATO and the EU should be reformed to work more efficiently. Just beneath the surface, the French position is evident. According to Paris, NATO should not become a global alliance, so it should not expand its geographical borders or be used everywhere in the world.

(c) Responses to New Threats

National security strategies select strategic objectives (goals), identify resources to be used (means) and explain how the goals will be achieved (ways). The 2008 White Paper describes relevant responses to new threats (counter-terrorism, trans-national, civil emergencies… strategies and policies, new non-traditional missions…) through analysing the defence and security equipment used by Armed Forces and Security Forces and allocating future necessary financial resources. The underlying meaning of national security is that it is no longer sufficient to merely respond to external security threats. An efficient security policy must complement defence, focusing on the protection of the national territory and population against threats that are no longer solely military. Terrorism constitutes a good example of this new form of threat; intelligence and counter terrorism have thus become one of the central missions of the different services devoted to defence and national security.

The knowledge and anticipation function is clearly to the fore, hence the doubling of the allocation of funds to military satellite programmes and the creation a Joint Space Command under the authority of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In the same way, the White Paper promotes detection and early warning capacities to counter ballistic missile threats to France in particular and to Europe in general. They include long-range radars and geostationary satellites that should preferably be developed through a European cooperative programme whenever possible. Intelligence collection is another priority and the MUSIS programme will replace the Helios satellites to upgrade imagery and the CERES programme will improve signal interception. Likewise, new response strategies are implemented to respond to newly identified threats such as cyber-war. A new concept of cyber-defence has been devised that will be coordinated by a new Security of Information Systems Agency, under the authority of the General Secretariat for Defence and National Security (SGDSN). On the other hand, in case of cyber-war, a counter-strike capacity has been created under the Chief of Defence Staff’s responsibility.

The 2008 White Paper details defence programmes on force protection, new-generation infantry fighting vehicles, combat and surveillance drones, nuclear attack submarines carrying cruise missiles, large amphibious ships (Mistral class) and so on. All the different services, Army, Navy and Air Force, list their own priorities that will have to reconciled by the National Defence and Security Council according to the priorities fixed in the 2008 White Paper and the available budgets. Security programmes are less developed with regard to the National Police, National Gendarmerie, border and civil protection, which alters the necessary balance between the security and defence elements of the Security Strategy.

Civilian and civil-military crisis management are other priority responses of the 2008 White Paper. It calls for an Operational Centre for External Crisis Management within the Foreign and European Affairs Ministry to be devoted to the planning and management of international crises, with an analogous Inter-Ministerial Crisis Management Centre to handle all crises occurring on the national territory within the Ministry of the Interior. Both will have an inter-ministerial approach to management and they will be open to external experts. In order to increase the public awareness of the new risks and responses, the Strategy foresees the improvement of nation-wide emergency systems and the opening of three new web sites devoted to preparing the population to cope with emergency situations, to prevent and respond to cyber-attacks and to promote research on national security. It also calls for the creation of a National Security Voluntary Service to ultimately replace the Citizen Reserve.

Institutional Modifications Resulting from the White Paper

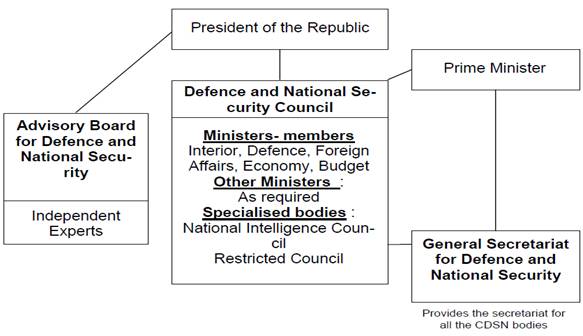

The 2008 White Paper defines the institutions entrusted with implementing the Defence and National Security Strategy (the ‘system’ depicted in Figure 1). It creates new institutions such as the Defence and National Security Council (DNSC) and modifies existing ones. The DNSC is chaired by the President of the French Republic, and it is responsible for all defence and national security-related matters. As a result of the former, the President is now at the centre of the system and deals with security matters which used to be under the control of the Prime Minister. The blurring of the boundaries between security and defence has changed the traditional division of labour between them and the increasing complexity of security risks and challenges has taken responsibilities closer to the Palace of the Élysée than to the Hotel Matignon.

Figure 1. The Defence and National Security Council

The DNSC defines the strategic guidelines for military planning, nuclear deterrence, military intervention abroad and crisis management at the international and domestic levels. It does the same on internal security planning with regard to terrorism and other matters affecting national security.[4] The DNSC can have plenary meetings, with the Prime Minister, the Ministers for Foreign Affairs, Defence, the Interior, Finance, the Budget and any others if required, under the direction of the President. It also can adopt more restricted meetings for ad hoc questions or specialised issues of intelligence and nuclear weapon. The General Secretariat for Defence and National Security provides the secretariat for all the different DNSC formations.

The National Intelligence Council (NIC) is a specialised group of the DNSC that provides overall guidance and assigns objectives and priorities to the French intelligence community. The NIC (Conseil National du Renseignement, CNR) officially follows up on the inter-ministerial Intelligence Committee which was allocated to the former General Secretariat for National Defence (Secrétariat Général de la Défense National) under the authority of the Prime Minister. According to Article 1122-6 of the Defence Code, its role is to define the strategic orientation and priorities in intelligence matters; it establishes the planning of human means and techniques of the various intelligence services. Under the direct authority of the President of the Republic, it can bring together the Prime Minister, the Ministers and the Directors of the different intelligence services. The mission letter addressed by the Head of State places him ‘under the authority of the General Secretary of the President’s administration… particularly in direct liaison with the Chief of Staff, the diplomatic advisor and Sherpa, and the interior advisor’. The diversity of intelligence-related departments suggested the creation of a National Intelligence Coordinator to advise the President, prepare the NIC sessions and serve as the point of contact for the Intelligence Services with the President of the Republic. Its coordination includes periodic meetings with the Directors of the intelligence services in order to set forth priorities for intelligence collection and human and technical requirements but without entering into the operational implementation of intelligence planning. The second specialised formation is the Council for Nuclear Armament (Conseil des Armements Nucléaires, CAN) in charge of the strategic guidance of the nuclear deterrence doctrine and equipment under the direction of the President and the participation of the Prime Minister, Defence Minister, Joint Chief of Staff, National Director for Armaments and the Director for military affairs of the Atomic Energy Commission.

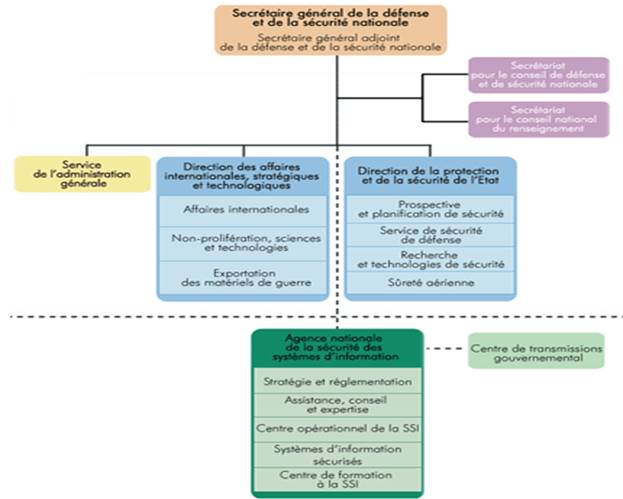

Another major institution reinforced by the 2008 White Book is the General Secretariat for Defence and National Security (see Figure 2). This inter-ministerial coordination body replaces the former Secrétariat General de la Défense under the authority of the Prime Minister and it comprises a permanent group of around 350 staff with a €100 million budget. Regardless of the greater clout of the President across the decision-making system, the influence of the GSDNS is based on its permanent structure, that gives it the necessary expertise to win the upper hand in the planning and implementation of defence and security policies. The GSDNS incorporates the Directorate for Strategic, International and Technological Affairs to supervise arms control, non-proliferation and strategic dossiers; the Directorate for the Safety and Security of the State co-ordinates the inter-ministerial responses to protect French territory and the population in addition to risks and technological assessments; and, since 2009, the Security of Information Systems Agency to protect France against cyber-attacks, cyber-terrorism and cyber-warfare.[5] Last but not least, the GSDN has two think-tanks: the Institute for Higher Studies of National Defence (Institut des Hautes Études de Défense Nationale, IHEDN) and the National Institute for High Studies on Security and Justice (Institut National des Hautes Études de la Sécurité et de la Justice, INHESJ).[6]

Figure 2. General Secretariat for Defence and National Security

With the exception of the functions of intelligence, crisis management and strategic guidance, the GSDNS covers most of the matters included within the national security concept but it is far from becoming the centralised advisory and supervising body that are the national security councils of the US and the UK.

Other institutions have also been created by the new White Paper. Within the Ministry of Defence, there are two bodies: the Joint Force Space Command, under the chairmanship of the Chief of the Joint Staff to deal with space operations, doctrine and programmes; and the Ministerial Committee on Investments (Comité Ministériel d’Invesstissement, CMI) that assesses the financial and economic aspects of military programmes before their adoption.[7] Within the Foreign and European Affairs Ministry, the Operational Centre for External Crisis Management has been dealing since July 2008 with early warning, crisis management and emergency and humanitarian responses abroad (Haiti, Senegal, Gaza and Air France flight 447 among others).

The New Balance of Power within the Executive and the Legislative

The 2008 White Paper has strengthened the President’s powers with regard to security and defence matters. It is important to specify that within the French constitutional regime, the President of the Republic is the Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces, while the political options are decided and implemented by the Government under the direction of the Prime Minister. The provisions of the French Constitution on the distribution of powers between the President of the Republic and the Prime Minister in defence matters are, to say the least, ambiguous. Article 15 of the Constitution designates the President of the Republic as the ‘Chief of the Armed Forces’ and Article 13 permits the direct involvement of the Chief of State in the nomination of Army Staff. Article 5, paragraph 2 presents the President as ‘the guarantor of national independence, of territorial integrity and of the upholding of treaties’. Article 8, although not directly concerned with the domain refers to it indirectly by stating the nominating power of the President vis-à-vis the Prime Minister and members of the government. Thereby, even during periods when the President and Prime Minister are from different political parties, the President can legitimately advance his choice for the post of Minister of Defence.

After the 2008 White Power, the French President remains at the centre of the decision-making system. The French President retains his prerogatives on nuclear deterrence and chairs the Defence and National Security Council and the National Intelligence Council. The President appoints the National Intelligence Co-ordinator and the members of the Advisory Board for Defence and National Security, all of them reporting or advising to the President. The extension of the defence concept to defence and national security has increased the role of the President with regard to the new spheres of defence and national security. In this respect, the creation of the CNR marked the peak of the presidentialisation of security and defence missions and ‘the marginalization of the Prime Minister is made official’ (Vadillo, 2009, p. 5) driven by Nicolas Sarkozy.

With regard to the role of the Prime Minister in the French Constitution, articles concerning the competences of the Prime Minister are not as numerous but are, however, just as important.[8] Article 20 specifies that the Head of the Government ‘conducts the nation’s policies’ and ‘has control of the Army’. Article 21 defines three prerogatives held by the Prime Minister in matters of defence: responsibility for national defence and the appointment of both civilian and military positions, subject to the provisions of Article 13. Besides, the former, the Defence Code specifies the responsibilities of the Prime Minister in its Article L1131-1: ‘the Prime Minister guides the actions of government in matters of national security. The Prime Minister, responsible for national defence, exercises the general direction and the military direction of defence’. Seemingly, in regards to these diverse articles, the use of the terms ‘security’ and ‘defence’ are, in the texts, relatively similar. However, as previously seen, practice has confined the concept of defence to military activities and the concept of security to civil and police activities. Thus, the introduction of an overarching concept of national security by the 2008 White Paper has overturned this ‘tradition’ and confused roles and responsibilities.[9]

The new White Paper does not change the attributions of the French Parliament, that is constitutionally limited in dealing with Defence matters. Only Article 34 mentions that: ‘the law determines the fundamental principles of organisation of national defence’. Nevertheless, the 2008 White Paper reinforces the role of the Parliament with regard to the intervention of the French armed forces abroad, the monitoring of White Paper reviews and bilateral defence and security agreements.[10] First, it is mandatory for Parliament to be informed about the nature and goals of any military operation abroad. The Government retains strategic and operational control of any action but Parliament has a say on its political and budgetary implications. Secondly, Parliament contributes to the implementation of the 2008 White Paper measures by legislating in defence and security bills as well as in the review processes. Thirdly, the extension of defence matters towards security increases the number of international agreements to be approved or ratified in the National Assembly. To cope with this enlarged role, parliamentary expertise is being developed in this area through the Permanent Commission of National Defence of the Armed Forces and by a Study Group on the Defence Industry.[11]

The Emerging Power of the Ministry of the Interior in the Field of National Security

The 2008 White Paper consolidates the role of the Ministry of the Interior. This began in 2002 when Nicholas Sarkozy was Interior Minister.[12] The new national security architecture, completed through the preparation and publication of the new White Paper on Defence and National Security, follows this logic through the importance accorded to the Ministry of the Interior in the new security strategy. This new architecture translates into a lighter structure in the central administration, the development of intelligence functions and the integration of the Gendarmerie Nationale in the Ministry of the Interior.[13] The ‘Security’ mission, secondly, was evaluated according to the General Revision of Public Policy (RGPP), the Finance Act 2009 and the multiannual framework of LOPPSI (2009-13).

The organisation and roles of the Ministry of the Interior have been slightly modified by the National Security Strategy. One of the leading problems identified by the experts for a better coordination between the Defence and Interior Ministries is the difference of mentalities between the two organisations and their respective defence and security cultures. The Ministry of Defence and the French Armed Forces essentially deal with the defence of the country and out-of-area operations, being obliged to develop long-term visions and ‘imagine the future’. Their strategic sense is reinforced by a long tradition of strategic, contingency and operational planning for military operations as well as for programming sophisticated armaments systems. On the contrary, the organisation and culture of the Ministry of the Interior is much more focused on the present, while long-term planning capabilities –ie, the future context in which police, intelligence and law enforcement capabilities will act– are delegated to several think-tanks (the IHESI in particular).

To remedy these weaknesses, a Planning Directorate has also been created in order toplan the protection of France’s territory and population, the protection of critical information infrastructures, economic intelligence and the management of defence and security zones. New transnational threats are also taken into account with the creation of a specialised service in the fight against the financing of illegal activities inspired by the American Office of Foreign Assets Control or the creation of a Joint National Training Centre (civilian and military) in the fight against chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear threats, and of a website for the prevention of and response to cyber attacks.

Another significant step is the creation of the Central Directorate for Interior Intelligence (Direction Central du Reinsegnement Intérieur, DCRI).[14] This two-fold body will protect, on the one hand, vital national interests by integrating anti-terrorist, counter-intelligence and economic intelligence resources while, on the other, it will ensure public order against violent street gangs and anti-system groups. Another new body is the Prospective and Strategy Delegationthat will reinforce the means available to the Ministry of the Interior to forecast and appraise every form of medium-term threat that might impact internal security and to prepare the most appropriate response by mobilising the competent departments.[15] The Central Directorate was created on 1 July 2008 from the merger of the Central Directorate of General Intelligence (dating from 1907) and the Directorate of Territorial Surveillance (DST, established in 1944).[16] The DCRI, the synthesis of these two bodies, deals with what is in the ‘national interest’ (a broad expression at best) and makes terrorism one of the four essential objectives of that mission. Its operations and structures are covered by the ‘Defence-Secret’ statute regulated by article R2311-6 of the Defence Code. That stipulates that ‘in conditions fixed by the Prime Minister, protected information or material that is classified at the Defence-Secret, as well as the organisational arrangements for their protection, are determined by each Minister for the department for which he is responsible’. The statute of the Defence-Secret of the DRCI, therefore, is entirely regulated through the authority of the Ministry of the Interior and the conditions set by the Government. The DCRI comprises eight branches, each of which have varying competencies, notably: terrorism, information technology, subversive violence, counter intelligence and international affairs. Such a vast array of competencies is required in order to meet the broad concept of national security and implies an increased cooperation between information services. Also, Bernard Squarcini, Head of the DRCI, is in regular contact with his counterpart in the DGSE, Erard Corbin de Mangoux (former advisor to Nicolas Sarkozy), as well as with Olivier Buquen, the new Economic Intelligence Officer. An example of its varying competencies is revealed by the fact that the DRCI has organised since 2008 almost 900 meetings with security directors of CAC 40 companies or with PME bosses.

According to the Ministry of the Interior communiqué, the DCRI wants a ‘French Intelligence FBI’. The reference to the American security model is therefore explicit, this also being further attested to by the creation of the National Security Council, which has as its primary goal the reproduction of the American ‘National Security Council’, under the direct authority of the US President.

The Central Administration of the Interior Ministry is also evolving in line with the 2008 White Paper, with the creation of the Directorate of Planning and Strategy (DPS) and the Directorate of National Security Planning (DPSN). The DPS is directly attached to the Cabinet of the Interior Minister. It is charged with strengthening the forecasting capabilities of the Ministry of the Interior with the goal of analysing all existing forms of medium-term threat and of preparing adapted responses in this regard. The DPSN is attached to the General Secretariat of the Ministry of the Interior. It coordinates the contribution of the Ministry of the Interior in the development of counter-terrorism plans and provides mission planning for the protection of territory and the population. Finally, with regard to the recommendations from the report of the Working Group presided over by Alain Bauer, the 2008 White Paper on Defence and National Security calls for a greater degree of amalgamation in the sector of strategic governmental research, through the creation of two centres of study and research with respect to ‘defence and foreign affairs’ and ‘homeland security’ respectively.

The integration of the National Gendarmerie in the Ministry of the Interior promotes a greater interaction and synergy between defence and security. Since 2002, under the presidency of Jacques Chirac, the Gendarmerie was partially placed ‘for use by the Ministry of the Interior for internal security missions’, but after 1 January 2009 the Gendarmerie is subject only to the Ministry of the Interior. This measure continues the logic of pooling resources desired by the head of state, for the better utilisation of public finances. As the 2009 Finance Act project for planning and implementation of Internal Security (Projet de loi d’orientation et de programmation pour la performance de la sécurité intérieure, Loppsi II) project impact study has specified: ‘Internal security policy has an obligation of continuous and dynamic performance’.[17] This decision will contribute to the assimilation of the 100,000 military personnel of the national Gendarmerie to the 120,000 police personnel. The general report on the 2009 Finance Act project backs the desired balance between the two ‘security’ mission programmes: the ‘National Police’ and ‘National Gendarmerie’ with an equal funding of €8.6 billion and €7.6 billion respectively. Nevertheless, the full transfer of authority to the Ministry of the Interior requires further adjustments of current legislation to clarify, eg, the requisition procedures of the Armed Forces by the civilian authorities. Up to now there was a clear distinction between civilian and military and several types of requisition were in existence. Nevertheless, all of them constrained the prefects to ‘requisition a regional gendarmerie commander to lend the assistance of military means in a city on a given date’ or in the framework ‘of a mission limited in space and time’. The Act 2009-971 of 3 August 2009 removes the requisition procedure from Article 2.[18]

Conclusions: Basic Findings, Main Trends and Personal Views

The 2008 White Paper on Defence and National Security represents a significant leap in the evolution of French strategic thinking and policies. It establishes the concept of national security, a concept that transcends the traditional realms of defence and internal security towards the overarching concept of national security.

The 2008 White Paper shows that the French concept of Security Strategy has considerably evolved. France has admitted the necessary interaction between internal and external security, asserting the necessity of a defence security continuum and of a multidimensional response to the new threats and risks. These are the striking points of the French new strategy.

It was prepared in the context of strategic statements being made at the European (the European Security Strategy of 2003) or national levels (the UK National Security Strategy of 2008 or the failed attempt of the German Government in 2008, among others). The 2008 White Paper adopted the same comprehensive concept of national security and the need for integrated inter-agency management as in the rest of strategies. Nevertheless, the presidential nature of the French system and the strong influence of the culture of defence reduced the scope and timing of structural reforms. The development of a new culture of national security and the improvement of inter-ministerial co-ordination will require a long period of transition. The fragmentation of the ‘system’ into several sub-systems at the presidential, prime-ministerial and ministerial levels prevents a clear picture on the state-of-the-art of the reforms and any assessment on its progress towards the goals declared in the White Paper.

In the 2008 White Paper, France decided to privilege intelligence, establishing the function of knowledge and anticipation, endowed with a privileged budget as well. The strategy’s highlights are the creation of new institutions with the President of the Republic at the core of the system –holding all the decision-making functions–, the normalisation of the relationship with NATO and, primarily, identifying the European framework as the future reference.

Regarding the reform of institutions, the focus on inter-ministerial management, with the final decision in the hands of the President of the Republic, shows how important it is to coordinate the different policies (economic, security, defence and diplomatic) to face the current security challenges. Nevertheless, the scope of inter-ministerial coordination is hindered by the division of the national security domains in the hands of the President (Defence and National Security Council and National Intelligence Council) and the Ministries of the Interior and Foreign and European Affairs (crisis management).

Clearly, the EU is the best tool to manage international crises and France is eager to encourage it to enlarge its military and civil capabilities.

French industrial interests are truly taken into account through identifying areas of proficiency, establishing a three-circle strategy, one of sovereignty with nationally-mastered technologies (nuclear power in particular), another through European cooperation, involving strategic technologies needing extra support, and, finally, a less strategic global circle, from which France is ready to buy assets, at the expense of its own industries.

Regarding the development of the UE as the framework of the French security strategy, it is clear that, beyond the White Paper’s declamatory assertions, the way the EU may act as a prominent security authority depends largely on factors France is unable to master by itself.

Still, one question has to be solved. With the budget crisis affecting all the EU’s member states, the French government decided in May 2010 to freeze the state budget and to reduce the defence investment budget. Although the exact amount of the budgetary reduction is still unknown (the most likely forecast being between €2.5 billion to €5 billion), this would have a clear influence on the research, equipment funding and industrial strategy in the White Paper and the Loi de Programmation Militaire, which details year by year the expenditure by the Ministry of Defence.

Like other European countries, France will have to face the implementation of a new security strategy with a downsized budget. This reality is another reason for pushing the Europeanisation of those strategies.

The 2008 White Paper also mentions the industrial and technological fields that will have to be mastered by France in the future, by 2025. With a view to the technical specialisation of European countries and considering it is impossible for any European country alone to master the whole spectrum of defence and security technologies, France specifies in which fields she deems it necessary to maintain, to a certain extent, a degree of strategic autonomy. More precisely: nuclear power, mastering spatial systems (access to space, ballistic missiles), naval systems (submarine-launched nuclear-powered devices) and information security. In other fields such as fighters, land defence or cruise missiles, France intends to seek and promote European cooperation.

Indeed, the general balance is as follows:

- The boundaries between Defence and Security are getting blurred.

- Responding to new threats through a multidimensional operation appears fundamental.

- New responses are to be found by means of civilian instruments (diplomacy, development aid, reduction of inequalities, training sessions for police forces, reconstruction of the state, etc) and of military ones (peace enforcement, peacekeeping, stabilisation missions, counter-terrorism, etc).

Fabio Liberti

Senior Research Fellow, Institut de Relations Internationales et Stratégiques (IRIS), Paris

Camille Blain

Research Assistant, Institut de Relations Internationales et Stratégiques (IRIS), Paris

References

Decree creating the Agence Nationale de la Sécurité des Systèmes d’Information, http://legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=LEGITEXT000020828572&dateTexte=vig.

Decree creating the Secrétariat Général de la Défense et Sécurité Nationale, http://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jopdf/common/jo_pdf.jsp?numJO=0&dateJO=20091229&numTexte=1&pageDebut=22561&pageFin=22563.

Défense et Sécurité Nationale (2008), Livre Blanc. Préface de Nicolas Sarkozy, Président de la République, Editions Odile Jacob-La Documentation Française, July.

French Constitution of 4/X/1958, http://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/html/constitution/constitution2.htm#titre2.

Gnesotto, Nicole (2008), ‘La défense européenne comme priorité de la présidence française’, in Fabio Liberti (Dir.), ‘Les défis de la présidence française de l’UE’, Revue Internationale et Stratégique, nr 69, spring.

Kirchner, Emil J., & James Sperling (2010), National Security Cultures. Regional & Gglobal perspectives, Routledge.

Lasheras, Borja, Christoph Pohlmann, Christos Katsioulis & Fabio Liberti (2010), European Union Security and Defence White Paper, a Proposal, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, January.

Liberti, Fabio (2010), ‘Le retour de la France dans le processus Européen?’, in Pascal Boniface (Dir.), ‘La politique étrangère de Nicolas Sarkozy. Rupture ou continuité?’, Revue Internationale et Stratégique, nº 77, spring.

Rapport d’information sur la stratégie de sécurité nationale, presented by M. Bernard Carayon, member of parliament, Assemblée Nationale, June 2004.

Vadillo, Floran (2009), ‘Le Conseil National du Renseignement; une presidentialisation sans justification’, Terra Nova, December.

Websites

National Agency for the Security of Information Systems (Agence Nationale de la Sécurité des Systèmes d’Information), http://www.ssi.gouv.fr/.

National Plan against A-flu (Plan National de Prévention et de Lutte ‘Pandémie grippale’), www.pandemie-grippale.gouv.fr.

Web Portal of Cyber Security (Portail de la Sécurité Informatique), http://www.securite-informatique.gouv.fr/.

Governmental Centre for Treating and Answering Cyber Attacks (Centre d’Expertise Gouvernemental de Réponse et de Traitement des Menaces Informatiques), http://www.certa.ssi.gouv.fr/.

Secrétariat Général de la défense et sécurité nationale, http://www.sgdsn.gouv.fr/

[1] Ordinance of 7 January 1959, dealing with the general organisation of defence,http://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=LEGITEXT000006069248&dateTexte=20090413.

[2] Available at http://www.livreblancdefenseetsecurite.gouv.fr/.

[3] It should not be forgotten that one of the major features of the so-called ‘rupture’ concept enounced by the President of the French Republic Nicolas Sarkozy has targeted the normalization of the relations between France and the Atlantic Alliance, through its reintegration into the military command, abandoned by General De Gaulle in 1958. See on this point Frédéric Bozo (2008), ‘Alliance Atlantique, la fin de l’exception française?’, working paper, Fondation pour l’Innovation Politique, Paris, February, http://www.fondapol.org/fileadmin/uploads/pdf/documents/DT_Alliance_atlantique_la_fin_de_lexception_francaise_ENG.pdf.

[4] See Décret nº 2009-1657, 24 December 2009, http://www.legifrance.gouv.fr.

[5] Décret nº 2009-834, 7 July 2009, http://www.legifrance.gouv.fr. The Agency has a Response Centre (Centre d’Expertise Gouvernemental de Réponse et de Traitement des Attaques Informatiques, CERTA) to assist governmental agencies to cope with cyber risks.

[6] For further information on these two centres, see http://www.ihedn.fr/ and http://www.inhesj.fr/, respectively.

[7] The Ministerial Committee is chaired by the Ministry of Defence, the Chief of the Joint Staff, the National Armaments Director and the Secretary-General for Financial Sustainability. They assess the operational needs, costs, procurement and potential offsets for every military project in accordance with the Order of 17 February 2010.

[8] The Ordinance of 7 January 1959 facilitated the Prime Minister’s task of coordinating the various security services. However, this state of affairs changed thereafter. The decree of 17 October 1962 created the Inter-ministerial Intelligence Committee (CIR) service of the General Secretary of National Defence (SGDN) placed under the authority of the Prime Minister. Its mission was to create a governmental intelligence plan, which the Prime Minister would submit for approval to the President of the Republic. Falling into disuse, the CIR was reformed several times, first by the government of Michel Rocard, through a decree of 20 April1989, then by the Government of Raffarin in 2004.

[9] During the 15 July 2009 session of the Senate relative to the law of military planning, Jean Pierre Chevènement warned against the confusion between ‘politics of defence’ and ‘politics of security’. ‘Article 15 specifies (…) formally that the President of the Republic presides over the high Councils and Committees of national defence and not the Councils of internal Defence and Security’.

[10] Article 35 seems to have fallen into disuse according to the evolution of the wording by the United Nations when it states that: ‘Contemporary conflicts in which France is susceptible to participate tend towards the maintenance or reestablishment of international peace and security; it is no longer a question of “war” and thus, of declaring “war”’. Thereafter, during the war in Kosovo, the President of the Republic directly addressed the French public on 24 March 1999 to announce the beginning of combat, after a speech by the Minister of Foreign Affairs addressing the Commission of Foreign Affairs of the National Assembly in order to inform it of the possibility of recourse to coercive measures.

[11] Like the other permanent Commissions, the Commission on National Defence comprises members designated according to the proportion of each parliamentary group; a member of parliament can only belong to a single Commission.

[12] It is interesting to note that the governmental culture regarding security was perpetuated when Nicolas Sarkozy occupied the positions of Minister of the Interior, Minister of Homeland Security and Minister of Local Liberty under the first two Raffarin Governments (May 2002 and March 2004, respectively) and Minister for the Interior under the Villepin Government (May 2005 to March 2007), before becoming President of the French Republic. The title of Minister of State, granted during his tenure as Minister of the Interior under the Villepin Government, reveals the importance of protocol and suggests that Homeland Security is being considered a governmental priority. It also appears that defence, a domain traditionally revolving on collective interest, is little by little being substituted by the notion of ‘Security’ that underlines individual protection. There is thus a real transition, in both the discourse and in the realisation of societal concerns, regarding the notion of (collective) defence to that of (individual) security.

[13] Among other changes, the capabilities of the Ministry of Interior have been improved with the capacity development of the DGSE counter-terrorism material; the creation, by decree of 27 June 2008, of the Central Directorate of Interior Intelligence, the coordination of National Police and Gendarmerie assured by the Counter Terrorism Coordination Unit (UCLAT) and the Act of 23 January 2006 concerning counter-terrorism or the Vigipirate Plan that is evolving according to the changing evaluation of threats.

[14] The DCRI was created in July 2008, when the Minister of the Interior was Michèle Alliot-Marie, in order to merge the General Intelligence Directorate (Renseignements Généraux, around 4.000 police) and the Directorate for the Security of the Territory (Direction de Surveillance du Territoire, 2.000 police).

[15] Despite the traditional influence of the military and diplomats, several individuals whose professional culture is strongly aligned with the Ministry of the Interior have been appointed at the head of strategic posts in security and national defence, which confirms the increasing blurring of defence and security after the 2008 White Paper. For instance, the DGSE, which is attached to the Ministry of Defence, is led, since October 2008, by Erard Corbin de Mangoux, who previously occupied the post of presidential advisor for internal affairs.

[16] The DST, placed under the authority of the General Directorate for the National Police, has historically been entrusted with the task of counter-espionage. After the end of the Cold war, it has become competent in the domains of counter-terrorism and the fight against proliferation, as well as the protection of France’s economic and scientific heritage (economic intelligence). The Central Directorate of General Intelligence, meanwhile, participates in the defence of fundamental interests of the State and contributes to Homeland Security. It was placed under the joint authority of the Prefects and of the General Directorate of National Police.

[17] The Project Loppsi II was presented on 27 May 2009 by Michèle Alliot-Marie to the Cabinet and it contains the strategic guidelines for internal security policy over the period 2009-13.

[18] If the Gendarmes keep their military status, they will not placed under the direct authority of the Prefects named by the head of state and ‘representatives of the State and each of its members of government in the collective territories’ (article 72 of the Constitution). The Army General Yves Capdetpont, former Major General of the Gendarmerie and former Inspector General of the armed forces, in a position dated 28 October 2009, warns against the confusion of the principles of decision and execution that this measure risks creating: placing the gendarmes under of the authority of the Prefects places them in a position where they have ‘the power to decide and the capacity to execute’.