A common notion circulating inside and outside Spain is that over half of young Spaniards (aged 16-24) are unemployed –a ‘fact’ which furthers the image of deep crisis in Spain–. The world’s most prestigious media report on such youth unemployment with alarm, contributing to this new ‘Black Legend’ of Spanish failure. The truth, however, is that only 22% of 16-24 year olds are unemployed. That is just over a fifth, while the vast majority are studying or working.

So where does this figure of 50% come from? From Eurostat, the European statistics agency. It uses two measures of youth unemployment: one is calculated on the basis of all young people (this so-called unemployment ‘ratio’ gives the 22% figure) and the other on the basis of those in the labour force, ie, actively employed or seeking employment. It is the second formula (or unemployment ‘rate’) which puts Spanish youth unemployment at 55%. This formula makes sense among adults, especially men, practically all of whom are likely to work or seek work until retirement age. But applying it to an age group where most people are still in education or training distorts its meaning, even if it sheds some light on the subject. The problem is that Eurostat only publicises the second figure and not the first.

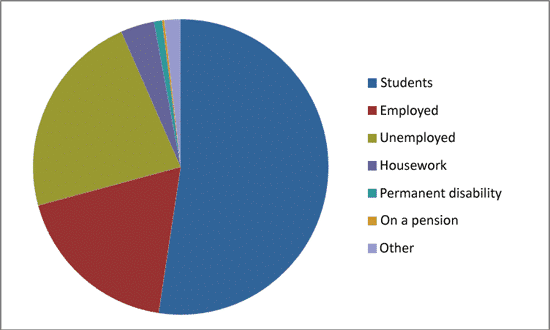

Data from the Spanish Labour Force Survey show the number of 16-24 year olds in the labour force only totalled 1,678,000 (as of the fourth quarter of 2012), compared with 4,113,000 individuals in that age group. In other words, only 41% of the group were working or looking for work. Most of those neither employed nor job hunting –89%– are students. A much smaller proportion is accounted for by the group of women dedicated exclusively to housework, and finally a small group of ‘others’ who are essentially NEETs (known as the ‘ni-nis’ in Spain) –those neither in education or employment nor seeking work (73,000 people)–.

Clearly it is not good news that over half of job seekers aged 16-24 cannot secure employment. Eight out of 10 of the unemployed in that age group have worked previously, meaning their unemployment is a result of job destruction wreaked by the crisis, especially in the construction sector where many of these young people gained employment during the property boom years, stopping their studies. The young and unemployed also include a significant number of immigrants who either were directly integrated into the labour market when they arrived in Spain in the boom years and have now lost their jobs, or reached working age in the midst of the crisis. Their demographic weight among the youngest members of the population is sizeable: those born abroad account for 18% of all 16-24 year olds resident in Spain, according to the Spanish municipal register (as of 1 January 2012). Unemployment is substantially higher among foreign-born young people than among native Spaniards (28% compared with 21%), and research into the former group worryingly reveals their low inclination to keep studying beyond compulsory education.

However, as Luis Garrido shows,[1] the mass employment of young people of this age ended in Spain following the oil crisis in the mid 70s. Then, the destruction of industrial employment changed the strategies of young people and their families, who thereafter opted to continue their education beyond compulsory schooling. The employment rate among young men aged 16-19 in 1964, the first year of the Labour Force Survey (Encuesta de Población Activa or EPA), was 70%, and over 80% among 20-24 year olds. Today this would be inconceivable, since the situation reflected a backward country with an abundance of unskilled jobs. Since the crisis of the mid 70s, the youth employment rate (ie, the relationship between the number of employed and the total population of this age group) has continually decreased while the number of students has increased. This positive modernisation process contributes to a more productive economy where unskilled jobs are increasingly scarce. In fact, as Luis Garrido demonstrates, the percentage of young people neither studying nor working is lower in this crisis than in the previous one of 1994.

Disseminating such alarmist information on youth unemployment, which is one-sided and thus biased, not only has a negative impact on Spain’s image abroad but also contributes internally and at the European level to the prioritisation of employment policies aimed at this age group. These include the recent European Commission initiative to support youth employment for under-25s. And yet in reality the unemployment situation is more worrying for older groups of 25-34 year olds. That is when young people have finished their training and embark on a period of great difficulties to start their own families.

[1] Luis Garrido Medina (2012), ‘Para un diagnóstico sobre la formación y el empleo de los jóvenes’, Cuadernos nr 2, Empleo Juvenil, Círculo Cívico de Opinión, www.circulocivicodeopinion.es.