Recent headlines have underscored the entrance to the German Parliament of a xenophobe party –Alternative for Germany (AfD)– for the first time since the Second World War. But the real news is that despite the arrival of more than a million refugees in 2015 and 2016 –for which Merkel received heavy criticism from both within and outside her party– she has won a fourth election. This is an unprecedented feat among Western democracies in the last decades, a period during which, as Moises Naim has pointed out, it has become easier to gain power but also easier to lose it.

If she finishes her new term, Merkel will have been in power for more than 15 years, a good measure of her political stature and cunning. However, this historic achievement –only comparable to the trajectory of Helmut Kohl (and in his time there was no Internet)– comes with a high price. Her centrist policies have stimulated the parties of the extremes, in particular, the AfD, which at the time of the last election (2013) did not yet even exist.

“As in other European countries, the hegemony of the centre has come under attack from the extremes and collapsed”

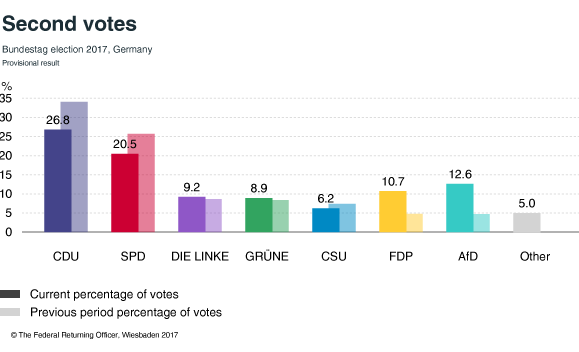

The appearance of the AfD in the Bundestag constitutes a political earthquake but, as is often true with real earthquakes, it was more than expected. The only uncertainty was its ultimate intensity. In the end, the AfD captured 13% of the vote and nearly 100 seats in the Bundestag, becoming the third largest political force. This has shocked a nation that since the Second World War has always prided itself on the absence of xenophobic parties from its parliament.

Thus, the German exception has come to an end. Like its neighbours –France, Austria, the Netherlands and, of course, Poland–, the German people, and their elites, will have to deal with the problem of an exclusionary, anti-globalisation, anti-EU and anti-immigration nationalism.

Up to now it had always been said that German politics were boring. Merkel made sure of that. She formed stable government coalitions, twice with the Social-Democratic SPD and once with the Liberals of the FDP, and she has always governed from the centre. The last grand-coalition government held 80% of the parliamentary seats. But as in other European countries, the hegemony of the centre has come under attack from the extremes and collapsed, not sufficiently to defeat Merkel but enough to radically change the political landscape. Together Merkel’s Christian-Democrats and Schulz’s Social-Democrats lost more than 100 seats.

The AfD benefited from the protest vote. Nearly a million of its votes came from Merkel’s CDU: the discontented with the Chancellor’s open-door refugee policy. Concentrating on the centre, Merkel has (consciously) ignored her right flank.

“The regions that have voted the most for the xenophobic party are those that have the fewest immigrants”

It should also be emphasised that many AfD votes came from Eastern Germany. This is striking. The regions that have voted the most for the xenophobic party are those that have the fewest immigrants. The motives appear to be fed by fears of what changes might come rather than by a rejection of the status quo. The vast majority of Germans, including AfD voters, acknowledge that they enjoy a high standard of living. It is also true that both inequality and precariousness do exist in Germany. Many of those having a hard time voted for Die Linke (the extreme Left) or the AfD. Another interesting piece of data is that the extreme-right mobilised more than a million voters from among those who previously did not vote. In fact, AfD had more Twitter and Facebook traffic than any other party.

The AfD will therefore bring a lot of noise with it to the German Parliament. But that will not be the only change. The Social-Democrats have already said they are now in the opposition. The election results were the worst in their history and they appear to have been significantly damaged by their participation in the coalition government with Merkel. They have no choice but to rethink their discourse and reform. Social Democracy is on the decline throughout Europe, partly because its parties have not effectively adapted to the new times. The industrial revolution saw the birth of workers’ parties; the digital revolution could end up burying them. Nevertheless, it is important that the SPD is in the opposition because otherwise the AfD would become the leading opposition party, lending it an influential spotlight in the Parliament and the media.

With the SPD out of the equation, Merkel has only one possible coalition option: agreement with the FPD and the Green Party, both of which would be incorporated into the Jamaica coalition, named after the colours of the three political groups (black, yellow and green). But any such coalition deal will be tough. The Liberals and the Greens occupy opposing parts of the spectrum on many issues, including European integration, the phasing-out of diesel fuel and immigration policy. Nevertheless, if anyone has experience in forming coalitions it is Merkel. If she cannot form another, her options will be either to govern in minority (complicated, but possible) or to call for new elections.

“The Liberals have drawn a red line regarding many of Macron’s proposals”

The normal thing, of course, would be for a sense of duty to prevail and for the three parties –actually four if the CDU’s Bavarian partner, the CSU, is considered– to engage in lengthy negotiations, presumably until Christmas, to produce a government agreement along well-defined lines. The Greens would likely to get the Ministry of Foreign Affairs while the Liberals would presumably be assigned the Ministry of Finance (which could imply replacing Schäuble, another high price to pay for Merkel) or of the Economy (which would make sense because the FDP is a pro-market, pro-business party).

The Liberals have drawn a red line regarding many of Macron’s proposals for advancing the integration of the monetary union. This has caused concern in Spain. In principle, the FPD opposes a euro-zone budget of any substantial size and would like to dismantle the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), created during the latest crisis to assist countries under financial stress, Spain among them. It remains to be seen whether it will maintain its hard-line stance. The Liberal leader, Christian Lindner, is a young and pragmatic politician who knows that with barely more than 10% of the vote he cannot impose his point of view on all fronts. He could, for instance, get a substantial tax cut and economic reforms in exchange for giving ground on Europe, where the Greens will want Merkel to be more generous.

At any event, it is a mistake to think that Germany would have earmarked billions of euros for a euro-zone budget with Schulz either in the government or as a minor partner. The German consensus position on this question is long-established. From Berlin’s perspective, a real budget would not only imply the mutualisation of debt, but would necessarily also mean control over spending and income. This is to say that Eurozone countries would have to cede some fiscal sovereignty. And it remains to be seen if France, even with Macron (Lindner has repeated this point several times), is even willing to do so itself. Another thing altogether would be for such a budget to go to an incentive fund for reforms in different countries. In the end, the real question is: what is this common budget for? If it is for a macroeconomic stabilisation mechanism that costs various percentage points of the euro-zone GDP, then opposition will come not just from Linder, but also from Merkel. If the idea is to create a common fund of up to €50 billion to be destined as economic aid to support concrete reforms, then an agreement might be possible.

Lindner and Macron have a common agenda: digitalisation, an overhaul of education, strengthening of active employment policies, invigoration of entrepreneurship and modernisation (and heightened transparency) of the administration. This is not the dream of the federalists, but it could help to strengthen the monetary union by fostering a greater confidence –and, who knows, perhaps even convergence– among member states.

In the end, in the wake of the elections, Germany now looks more like France. The two countries, along with most other Western countries, now face an axis of tension between one part of the electorate which is open and cosmopolitan and another which is nativist and nationalist. The good news is that the Jamaica coalition (if it takes shape) will be formed by three parties that are pro-Europe and in favour of openness (although Lindner did flirt with Euroscepticism during the election campaign). The fear is that these parties will prove to be incapable of protecting and empowering the nativists so that they can look more favourably on European integration and globalisation.

For Merkel the real work will start at home because if in the end there is a Jamaica coalition, it will be dominated by West Germany (where the three parties have much of their support) as opposed to East Germany (where they have less). To bridge the gap will be crucial to the European integration project: if the average German sees that investment in the East has been worthwhile, then he will also view the creation of a European fiscal union more favourably.