The good governance of energy resources and its role in the economic development of oil and gas producing countries is an area of growing interest in the global agenda. Contrary to China and the US under the Trump Administration, the EU is one of the few major importers of oil and natural gas promoting good resource governance standards in the Global South. It does so by supporting both multi-stakeholder initiatives like the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) and by enacting its own regulations to enhance transparency through monitoring and reporting in the transparency and accounting directives (Directives 2013/34/EU and 2013/50/EU). The normative race to the top between the EU, the US and the EITI slowed down when the Trump Administration withdrew from the EITI and undermined the Dodd-Frank Act by repealing its Section 1504, requiring extractive companies to publicly report its payments to foreign governments.

Nevertheless, analysing the role of the EU in improving the governance of energy resources goes beyond its institutional contribution to assess the practical implications that such a normative approach has on European oil and gas import patterns. The question is whether the EU’s oil and gas imports have been affected by the policies of improving transparency and good resource governance in the extractive sector, or if these policies have been ineffective in shaping their geographical origin and therefore in fostering good energy resource governance in oil and gas producing countries. In a recent article published in the Journal of Energy Policy we provide empirical evidence on ‘The European Union and the Good Governance of Energy Resources: Practicing What It Preaches?’

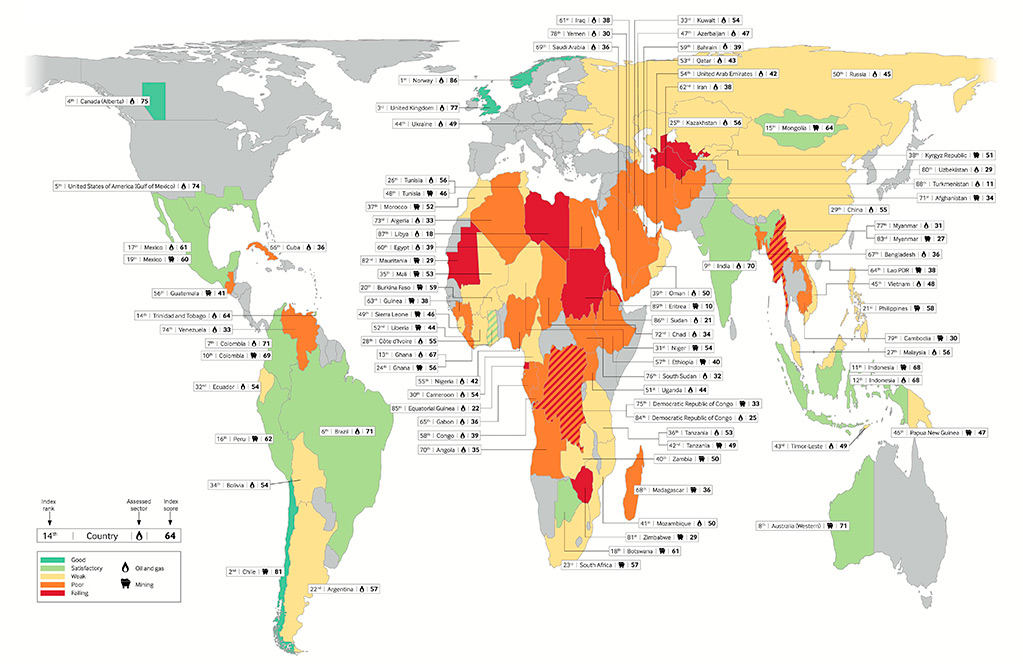

The article differentiates two approaches to good energy resource governance: the narrative of ‘governance as transparency’, which relates good resource governance to norms providing reporting, monitoring and disclosure; and the factual measuring of good resource governance measures in producing countries. Critics of transparency suggest that either transparency might not be enough to tackle corruption or that it is heavily influenced by major stakeholders, such as institutions, lobbies and companies, rather than local stakeholders. While the 2019 update of the EITI standard demands comprehensive and reliable disclosures by reporting entities, relevant aspects such as revenue management and an enabling environment, cannot be addressed just with transparency. By contrast, the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) offers the Resource Governance Index (RGI), which measures the quality of governance in the oil, gas and mining sectors of 81 countries.

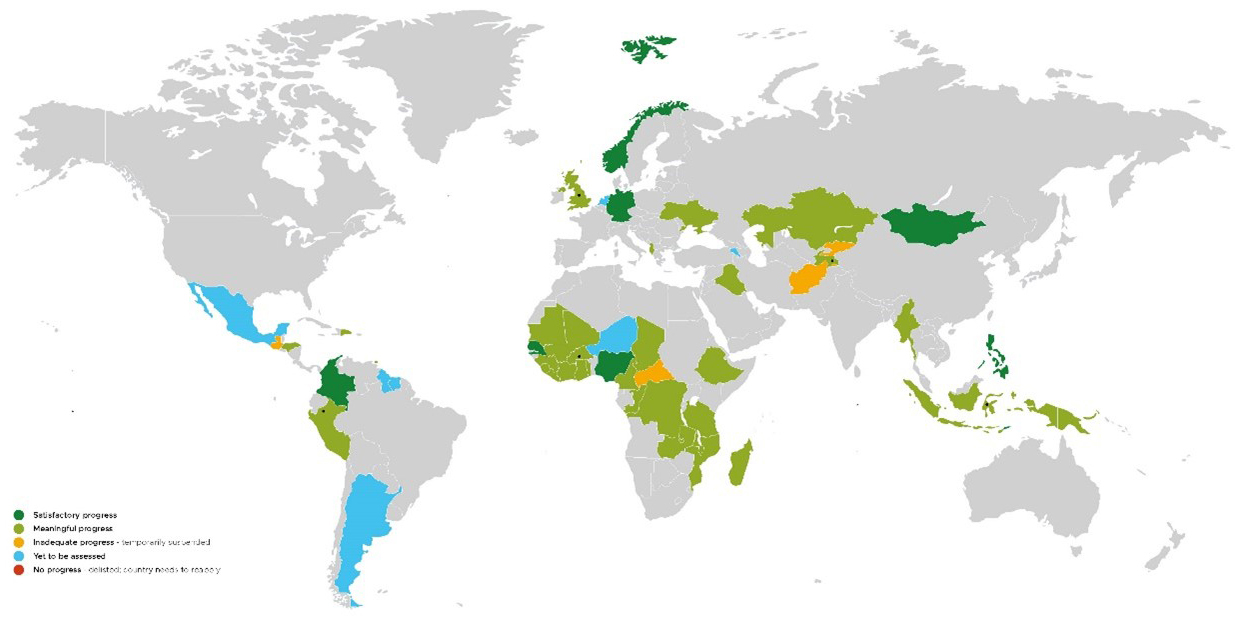

According to our results, the quantity of oil and gas imported by EU countries is related positively to the transparency in energy resources’ management in exporting countries (as proxied by EITI membership). However, we have not found empirical evidence supporting a relationship between the quantity of oil and gas imported by EU countries and good energy resource governance in exporting countries (as measured by RGI). These results suggest that energy governance seems to play a role in the origin of the EU’s oil and gas imports, showing that the narrative of ‘governance as transparency’ is gaining traction in the EU. The finding that EU member states tend to import more oil and gas from EITI members than from non-members reveals a preference for transparency, which becomes operational through the transparency and accounting directives. This offers a first step towards improving oil and gas governance in producing countries, signalling a propensity to value transparency and fostering the upgrading of EITI.

In brief, while the EU continues to import oil and gas from producers with low or even failed resource governance levels, public policy clearly matters: enacting European disclosure legislation, as well as supporting institutional innovation and benchmarks (like EITI and RGI), influence the behaviour of companies regarding international partnerships, investments and reputational strategies. Admittedly, this may be criticised as ‘cheap’ foreign policy insofar as it does not address the issue with more stringent policies, like strong conditionality or import bans from poorly governed countries. But it provides the EU with tools allowing soft external governance aligned with its values and, in the long run, with its interests too: good energy resource governance not only implies a greater security of supply to the EU, but also a geopolitically smoother energy transition in oil and gas producing European neighbours.