Theme

How do the governance structures of the Plans for National Recovery and Resilience (PNRRs) of Spain and Italy compare?1

Summary

This paper analyses the governance structures of Plans for National Recovery and Resilience (PNRRs) of Spain and Italy, offering a comprehensive outlook on their key strengths and shortcomings, with the aim of drawing attention to the areas that demand further scrutiny for their optimal implementation. It also looks into the similarities and differences between the two countries as regards their engagement with potential stakeholders, the inclusion of different players in the consultation process for determining projects, and the planning and organisation for selecting the projects themselves.

Analysis

(1) Introduction

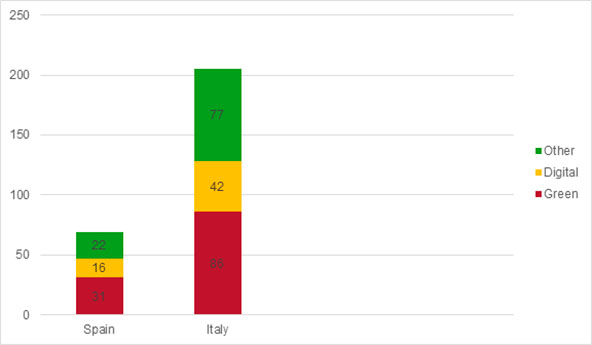

Spain and Italy have a significant weight when it comes to shaping the EU’s future. The European Commission’s green light on their Plans for National Recovery and Resilience (PNRRs) has sent the crucial message to the entire European Community that the Next Generation EU (NGEU) project has been officially launched. As Spain and Italy are the largest recipients of NGEU funds, their use, as outlined in their PNRRs, seems pivotal to their objectives. In other words, restoring a move towards further European integration is highly dependent upon the performance of Spain and Italy. For this reason, their PNRRs have attracted a great deal of scrutiny. Experts2 have expressed some scepticism about their implementation due to concerns about the two countries’ capacity to carry them out.

While experts have praised the two countries’ ambition in setting their goals, they have also rapidly spotted significant shortcomings in the methodology for their execution. In general, the Spanish and Italian plans are noteworthy because they sketch a thorough programme for the modernisation of their economies and societies. Chiefly, they do so by identifying significant structural weaknesses that have burdened them for years. However, it has been widely acknowledged that the way Spain and Italy expect to reach their objectives has major drawbacks, mainly due to the poor outline of the governance structure of their PNRRs. It is uncertain whether Spain and Italy have the capacity for the appropriate expenditure and implementation as outlined in their PNRRs.

Since the governance of the Spanish and Italian PNRRs is what should transform ambitions into reality, it is important to have a clear view about where it falls short in order to draw attention towards the major inconsistencies that deserve to be addressed promptly. Accordingly, this paper’s next section shows what the governance structure looks like for Spain and Italy’s PNRRs as of September 2021. The following one discusses the strengths and weaknesses of the two plans’ governance frameworks. The paper then looks at broader considerations regarding the implementation of Spain’s and Italy’s objectives, before concluding with some implications and final remarks.

(2) The governance structure of the Spanish and Italian PNRRs

The governance structure for the implementation of the Spanish and Italian PNRRs, as outlined in their plans, is found in Royal Decree-Law 26/20203 and 77/2021 Decree4 respectively. Both countries recognised the need for, and consequently approved, reforms aimed at simplifying their bureaucratic frameworks to ease the integration of their PNRRs in their respective legal structures. The reforms render more agile and effective the assimilation of NGEU funds. To do so, the legal modifications address the contractual field, subsidies and conventions used to incentivise greater public-private cooperation and Public Administration re-organisation. It is under the latter categorisation that one can find the creation of a governance structure entrusted with managing the practical implementation of the PNRRs.

(2.1) Spain

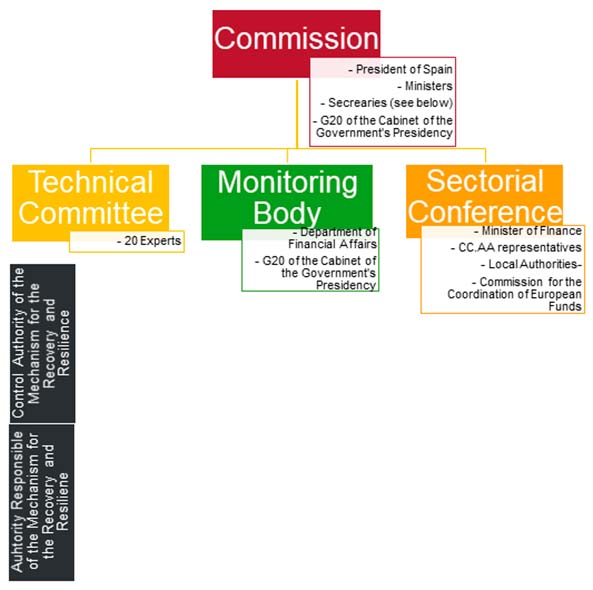

The governance structure described in the 36/2020 Royal Decree-Law5 is an informed centralised structure aimed at looking at ideas and proposals deriving from leading socio-economic actors. In this respect, the governance process can be viewed as having a bottom-up approach.6 The Commission of the PNRR is at the head of the whole structure, entrusted with making the ultimate informed decision upon the approval of projected proposals. The Technical Committee and Sectoral Conference are additional bodies in charge of informing the Commission of their preferences that, in turn, should be taken into consideration and translated into practical projects and directives.7 ,8

The Sectoral Conference gathers the representatives of the Comunidades Autónomas (CCAA, ie, Spain’s various regional authorities) and localities in the delineation of concrete projects responding to the PNRR’s objectives. The Minister of Finance oversees advisors that are knowledgeable on the relevant parts of the plan, but representative of each CCAA. These representatives have the possibility of requesting the presence of additional representatives of the Local Administrations. Lastly, the Commission for the Coordination of European Funds supports the organisation of these Sectoral Conferences. This is led by the Ministry of Finance, to ensure the appropriate potential usage of the funds with regards to the general guidelines of NGEU’s objectives.

Moreover, different Ministries are encouraged to create forums to involve the active participation of society in voicing ideas. To this end, they are advised to create High-Level Forums, whereby relevant actors to the different PNRR’s objectives are invited to share their views and recommendations. Additionally, Ministries should also organise Social Forums, whereby business organisations and unions are to share their concerns and priorities.9

Formed by 20 civil servants, the Technical Committee has the responsibility to administer the technicalities of the implementation process. For example, the Technical Committee conducts thorough analyses to propose the models, guidelines and manuals relating to procedures and general handling of investments. To do this, it can create Working Groups formed by members of NGOs, the private sector, students and so on, drawing on the expertise required.10 Additionally, it drafts the practical documentation and instruments needed to match the PNRR’s different objectives with relevant project and related expenses –eligible for (public and private) financing–. In other words, the Technical Committee creates the fundamentals for the development of projects that bring to fruition the intended objectives stated in the PNRR.

In turn, the Technical Committee proposals are passed to the Commission, which either approves or sends them back, considering the information received from the Sectoral Conference. The Commission is formed by Spain’s Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, all the Ministers, the Secretary of State for the Economy and Businesses’ Support, the Secretary of State for Social Rights, the Secretary General for European Funds, and the Secretary General for Economic Affairs and the G20 of the Presidency of the Government. Clearly, the ultimate decision-making body is essentially political.

Finally, the Monitoring Body, formed by the Department of Financial Affairs and the G20 of the Presidency of the Government, has the task of constantly and directly reporting to the Spanish Prime Minister of any developments on the PNRR’s implementation. Additionally, it acts as the Secretariat for the Commission.

The actual oversight and control of the PNRR’s execution is in the hands of the Authority Responsible of the Mechanism for the Recovery and Resilience, and of the Control Authority of the Mechanism for the Recovery and Resilience, respectively. The former acts as a coordinating body between the various Ministers, Public Administration, CCAA, Local Authorities, etc, as well as Spain and the EC in reporting the progresses made, which is needed to receive NGEU funds. It also coordinates the Technical Committee and is the Secretariat for the Sectoral Conferences. Instead, the Control Authority is embodied by the General Intervention of the State Administration (IGAE), and it makes sure that the plan is executed in accordance with European regulations. Moreover, the IGAE is flanked by the National Anti-Fraud Coordination Service, protecting investments.

(2.2) Italy

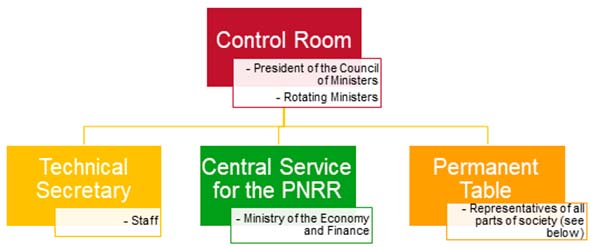

Italy’s governance structure, found in the 77/2021 Decree11 for the actualisation of its PNRR, is very similar to Spain’s. However, the centralisation of powers seems far more deep-seated.12 The governance is headed by the Control Room, which is in charge of orchestrating the selection of projects that materialise the PNRR’s objectives. Such a selection is informed by the Technical Secretary and the Permanent Table, which share technical knowledge as well as general interests that steer the design of the practical execution of the plan.13 ,14

The Control Room exercises coordinating and directive powers for the realization of the PNRR. Presided by the President of the Council of Ministers – Mario Draghi, it is formed by constantly rotating Ministers, that alternate according to an agenda that follows the various areas of the PNRR. Meaning that, the relevant Minister, together with their support team, participates in the Control Room’s meeting when his Ministry is involved in the discussion of a particular theme of the plan. Moreover, Regional representatives participate in these conferences when issues that relate to their territories are examined. Also, representatives of identified implementing bodies, as well as representatives of the respective associative bodies and chamber of commerce, can take part in the Control Room meetings when appropriate.

A Permanent Table is established to conduct the discussion at a lower political level, in order to advise the various Ministries participating in the Control Room. The Permanent Table is formed by representatives of social organisations, of the governments of the Regions and of Local Authorities together with their respective associations, representatives at the industry, university and research system levels, and representatives of the civil society at large. In turn, this body should be able to identify relevant profiles for the practical execution of each part of the plan. Additionally, it should be able to indicate to the Control Room any possible issue that might hinder the optimal implementation of projects. In sum, by gathering the knowledge of the territories and the various parts of society that are to be involved in selected projects, the Permanent Table ensures, in principle, a smooth and effective performance.

Notably, the decision-making power lie in the hands of the President of the Council of Ministers, which is informed by the discussion with all the actors present in the Control Room. These decisions made by the President of the Council of Ministers are assisted by the Technical Secretary. Existing until the completion of the plan, this body reports on the monitoring and oversight done by the supervising body, the Central Service for the PNRR. Additionally, the Technical Secretary ensures the transparent communication of these decisions to the Italian Parliament and the Council of Ministers.

The oversight and control of the PNRR’s implementation is carried out by the Central Service for the PNRR, which is essentially the Ministry of the Economy and Finance (MEF). An additional department is instituted within the MEF in charge of auditing the whole process as a way of monitoring the legality of the process and anticorruption. In turn, this body communicates with, and reports to, the EC about the progress made on the practical realisation of the plan and on the intended projects. To do so, any administration that takes charge of the practical implementation of the projects has to constitute an office reporting to the Central Service of any development made in that direction. Indeed, in the end, it is either the Central Administrations, and/or Regions and Local Authorities that are in charge of enacting the practicalities of the projects –depending on the required specific competences required–.

(3) Critical assessment of the governance of Spain and Italy

It has been widely recognised that besides their good intentions, the governance structures of Spain and Italy carry important shortcomings. Specifically, many points that are fundamental for the successful implementation of the plan have been put aside for a later discussion.

Spain’s strongest asset in its outlined governance structure is the extent of involvement of the various actors of society in the discussion regarding translating the PNRR’s objectives into reality. In a way, Italy also shares this feature; however, Spain does it in a much more systematic and comprehensive way. This can already be perceived in the space devoted in the Spanish PNRR to the Social Consulting section, which is completely absent in the Italian one.15 Additionally, while Italy involves all the different sectors of society within the discussion through the Permanent Table, Spain organises separate consulting forums for each, which in turn individually speak up to the relevant Ministry about their perception of the topic at stake. Although there is no system in place that ensures that such views are integrated in the projects themselves, it is still more likely that –in the Spanish case– all perspectives are properly considered. This is because they are delivered in an organised and efficient way.

On Italy’s side, the key strength of the country’s governance structure is the extensive involvement of relevant actors directly in the discussion that takes place where the decision-making power lies. Different players –such as Regions and Local Authorities, potential stakeholders and/or representatives of sectors of society thought to be directly involved in a project or matter under discussion– can request and be requested to speak in the Control Room, in front of the President of the Council. That is, instead of just keeping these voices discussing among themselves in a separate body –such as seems to occur in the Spanish case–, Italy also calls them into where the most important deliberation occurs. This feature significantly hands these actors a serious bargaining chip in determining the projects for implementing the PNRR. Again, while there are no checks-and-balances on whether these actors’ concerns, views and perspectives are incorporated in the projects, it is still a way to increase their chance of that being the case.

Crucially, both countries share criticisms regarding the broader governance performance that stems from the governance structure outlined above. The first issue that led many experts to express their concerns is the absence of an evaluation process for the selection of the projects themselves.16 Neither of the two PNRRs –the Spanish and Italian Decrees on the governance of their implementation– include measures to assess the quality of proposed projects. There are no details whatsoever from either party on how to estimate the likelihood of a project’s success if investments are directed to it. This is a risk as it might result in bad time-management and thus involve missed opportunities and a waste of resources.

There is a second problem in the governance of the two PNRRs: the opacity of the reasoning underlying investments.17 Generally, it is extremely unclear how Spain and Italy intend to manage the prioritisation of projects.18 No timeline related to what areas of the economy and/or sector of society should first be addressed has yet been specified. Most worryingly, the weight of public and private projects is blurred, as well as how much of these funds will be direct subsidies.19 Yet both Spain and Italy need to strike a balance between public and private investments so as to truly renovate their societies and economies in the long-term. So far, most of the delineation of how to invest NGEU funds occurs when it comes to public projects. However, financing only public projects would not attract enough returns to make societies perceive the benefits of the PNRRs. This is because returns on public investments are usually slower than their private counterparts and directed towards less innovative areas. As a result, the reforms attached to the plan that are more demanding are likely to be viewed as unjustifiable. Consequently, the overarching project risks failing.

While a bottom-up approach that lets entrepreneurs advance their ideas could be seen as a fair solution to these problems, it also bears serious biases.21 While this looks like the current state of play for deciding what specific projects are to be implemented, the Italian plan does not specify it at all. Instead, this idea comes out more neatly in the Spanish plan, as the country proposed –already before the officialisation of the PNRR– the Strategic Projects for the Economic Recovery and Transformation (PERTEs) framework.22 ,23 Accordingly, the best projects advanced, among those that fall under the most strategic areas as outlined in Spain’s PNRR, should be those implemented first.24

However, not only the absence of an evaluation procedure for the projects renders this framework uncertain. Also, such a way of selecting projects can seriously risk being biased towards actors that are well consolidated.25 This means that it is likely that funds will be directed to enterprises that already have a built-in capacity to carry out ambitious projects. Moreover, since the selection of projects is relatively highly centralised, this kind of approach, freed from any additional requirement that safeguards competition, is likely to rule out the possibility of the inclusion of start-ups and small and medium enterprises. Hence, this might prevent investing in more innovative solutions, which in turn could result in being more competitive as a country on a long-term perspective.26

Similarly, although political directives and/or regulations could be a solution to organise the prioritisation of projects,27 it is important to note that it also carries the danger of politicising the selection of projects. Indeed, both Spain and Italy, but especially the latter, have a relatively hierarchical governance structure, which, at the very top, is formed mostly by politicians. If no appropriate system of checks and balance is ensured, it might be the case that the decisions are highly steered by political considerations. Clearly this is an issue, as it risks drawing attention from project quality to mere political convenience.27 Thus, there is again a diminishing likelihood of the whole PNRR succeeding.

Finally, a fifth problem comes from the fact that both Spain and Italy have not yet presented a clear approach on how to physically implement the selected projects.28 ,29 For example, in Italy it is intended that either the Central Administrations and/or Regions and/or Local Authorities are to be in charge of their implementation, according to the specific competences that are required to deliver the projects. However, the determination of why and how the three best scores in meeting the expected competence is vague. Similarly, in Spain it is hinted that the CCAA together with the Local Administrations will have around 50% of the task of practical implementation,30 the other 50% being in the hands of the central government. Yet how to channel labour is still very unclear.31

(4) Added concerns on the implementation of the Spanish and Italian PNRRs

In addition to the critical points that arise from the very structure and outline of the Spanish and Italian governance as indicated in their Decrees and PNRRs, experts have also expressed unease with regards to the general implementation of the plans.

One matter of concern arises from the fact that, notwithstanding the high degree of centralisation of powers, implementation will truly depend upon the share of responsibility at the central, regional, and local levels.32 As both Spain and Italy have made clear, the involvement of the CCAAs and Regions –respectively– is a key aspect for implementation. This idea is based upon two important considerations. The first is that such an involvement would allow a better identification of where societies’ needs and potentials lie. This is because CCAAs, Regions and especially Local Administrations and Authorities have a closer look at smaller sections of society, given that they are responsible for a circumscribed territory.33 Secondly, and correlatedly, an involvement of these local entities increases the likelihood of stakeholder engagement and the sense of ownership.34 However, nowhere in the PNRRs or in their latest Decrees, do Spain and Italy outline whether and how they intend to consider the variation of capacities between their regional and local components in carrying out their stated objectives. For example, the Spanish Commission does not allow for the reinforcement of any kind of internal resources with NGEU funds. Yet it is obvious that in both countries such a variation is significant and long-lasting. If not considered, the plan’s implementation will vary significantly across their national territories, possibly leading to greater regional discrepancies.

In this relation, it is questionable whether Spain and Italy have the coordination capacity for the central-local relationship required for the plan’s implementation.35. Building onto the fact that localities differ extensively and have extremely different needs, it is likely that conflicts will arise between the central decision-making authorities and their regional and local counterparts. This is a clear example of the Principal-Agent problem, whereby the central decision-making representatives might have conflicting priorities with the local authorities in charge of executing directives. In the absence of a well-designed supervision framework, this might create serious bottlenecks in the implementation process.

On this note, it is worth pointing out a major difference in the governance of Spain and Italy’s PNRRs. Particularly, the Italian 77/2021 Decree includes clear indications of what should be done in the event of something going wrong in the implementation process.36 It discusses what kind of actions will be taken if Regions or Localities fail to respect either general directives of the PNRR or particularly assigned tasks that prevent the fulfilment of the overarching project. Also, it discusses what should be done in the event of a time-lag in the decision-making process. This might be a way to address and prevent the possible Principal-Agent problem. However, it remains unclear whether the execution of such a proposed solution to adverse scenarios will actually be feasible and effective in delivering the PNRR’s objectives.

The difficulty of delivery is accompanied by the difficulty of assessing certain projects included in the plan.37 Many parts of both the Spanish and Italian plans deal with matters that are simply unquantifiable when it comes to the evaluation of an effective delivery. One example is projects that lie under the Social Cohesion pillar. These projects deal with issues such as urban upgrading that are difficult to measure directly. Instead, for at least delivering an assessment, scholars have pointed out that the reliance on indirect indicators –such as the level of popular satisfaction– might still be a valuable solution. However, so far there is no framework for an assessment of this kind. In particular, there is no accurate framework for ex ante-ex post assessment. If not developed, both countries risk investing a great deal of money with little assurance that they will succeed.

Additionally, there is the issue of the Spanish and Italian communication strategies to their respective public opinions.38 This point is linked to that above in the sense that especially when it comes to the unquantifiable evaluation of projects, as are those that are mostly directly related to society, it is of paramount importance for communication to be as clear and straightforward as possible. People need to be aware of the various opportunities that surround them, as well as how to best approach them and what they should expect from them. Importantly, it is fundamental to understand that reforms will inevitably create winners and losers. In other words, especially in projects where the perceived benefits are likely to be blurred and ambiguous, it is crucial that communication is at its most transparent. Both Spain and Italy include in their PNRRs a section on how to do so.39 However, their intentions appear to be quite vague. For example, both countries seem to rely on websites to communicate with society about projects and their progress. Yet the development of online portals is contingent upon the smooth and upscale digitalisation of the Public Administration at all levels of government40 –which, so far, has scored poorly in both countries–. Hence, it seems questionable that the Spanish and Italian communication strategies will be as clear as intended. As Spain has finally published a comprehensive website with calls for projects, this will soon be spelled out.

Lastly, another topic of concern revolves around Public Administration reforms. The correct functioning of both countries’ plans relies on this type of reforms, which have rightly received priority as they have been for both Spain and Italy the first areas upon which work has been done after EC approval. The reforms are fundamental for an appropriate use of NGEU funds; additionally, they are essential for expediting the administration of the money and the projects. However, the progress made by Spain and Italy is still so far distant from completely exhausting the requirements outlined in the PNRRs. Reforming the Public Administration is an issue that will necessarily take time, especially considering that such reforms have been widely discussed and tried out in both Spain and Italy in the past, clearly without being successfully implemented. Therefore, it would appear that the execution of the other parts of their PNRRs will occur at times concomitant with the reformation of the Public Administration.41 Thus, this might represent another critical source of bottlenecks in the implementation of the various projects and thus in the realisation of the PNRRs’ objectives.

Conclusions

By exposing the way in which the Spanish and Italian governance structures have been designed through their respective PNRRs, as well as their most recent Decrees on the matter, the above analysis has highlighted similarities and differences between the two countries. Crucially, it has also pointed out that there are still many gaps in their planned implementation and administration in both countries.

There are two aspects that would seem to demand prompt action. First, a better delineated framework on the selection of projects, that clarifies the reasoning around prioritisation, assessment and evaluation, public/private distribution, how funds are delivered and who has a say in such decisions. To do so, it is paramount to organise and conduct an on-going evaluation analysis of investments and reforms. This would shed light on what works and what does not, as well as why they do or do not. Additionally, it is key to strike a balance between a bottom-up and a top-down approach. A way to do so would be to include politically independent experts that are knowledgeable in their field of expertise and are able to select suitable projects in an objective way.

Secondly, there should be a clear-cut scheme on how to manage the delivery of the PNRRs in light of the need to share responsibilities between the centre and local levels. This overarching theme has to do with finding coordination strategies based upon reforming the Public Administration and sharing information in a transparent way. To overcome these issues, immediate proposals at the central level should be advanced that can then be reviewed by the various CCAAs and Regions, which in turn can advise the central government on how to better incorporate their opinions. Ultimately, it will be the central government that needs to put forward such a programme and move accordingly. Relatedly, an impeccable work of auditing agencies, such as IGAE in Spain, is truly fundamental to ensuring an appropriate allocation of NGEU resources. Still, it is also important to hasten the oversight procedures of such agencies. Otherwise, bureaucratic deadlocks could undermine the successful implementation of the PNRRs.

Finally, it should be pointed out that the allocation of the workforce in both countries needs to be adjusted in a way that ensures the efficient execution of projects. The introduction of projects as outlined in the Spanish and Italian PNRRs opens up opportunities in several different sectors. As workers will be required for carrying out the implementation of the delineated plans, part of the existing workforce will necessarily have to shift towards these new opportunities. At the same time, the workforce might need to be incremented by hiring new workers to satisfy demand.

Spain and Italy are still in the early stages of their PNRRs, yet necessary adjustments and additions can and should be made to ensure that most of the blind spots are at least partially covered. This is critical, especially when considering that the two countries are the largest recipients of NGEU funds, and thus have the largest contribution potential for the recovery of the entire EU. If not addressed, the widely recognised gaps described above will lead Spain and Italy to lose face and credibility in the eyes of other Member States. In turn, losing credibility could threaten the entire NGEU project.

Alessandra Bonissoni

MA in International Relations and Economic (Johns Hopkins University) and Research Assistant Intern at the Elcano Royal institute (summer 2021)

1 I wish to extend my special thanks to Miguel Otero, whose supervision was crucial for the realization of this piece; and Federico Steinberg and Enrique Feás, for their thorough reviews.

2 For example, see Maddalena Martini (2020), ‘Why Italy and Spain will struggle to spend key EU funds’, Istituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale (ISPI), 27/XI/2020.

3 Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado (2020), ‘Real Decreto-ley 36/2020, de 30 de diciembre, por el que se aprueban medidas urgentes para la modernización de la Administración Pública y para la ejecución del Plan de Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia’, Jefatura del Estado, BOE, nr 31, 31/XII/2020.

4 Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana (2021), Decreto Legge 77/2021, nr 77, 31/V5/2021.

5 See note 1.

6 Gobierno de Espana (2021),España puede.Plan de Recuperacion, Transformacion y Resiliencia, 27/IV/2021.

7 OIReScon (2021),Guia Basica Plan de Recuperacion, Transformacion y Resiliencia, 1/VII/2021.

8 Carlo Romero (2020), ‘La Institutionalidad en el Plan de Recuperacion Transformacion y Resiliencia de Espana’, IberoEconomia, España en positivo, 7/XI/2020.

9 See note 4.

10 See note 4.

11 See note 2.

12 Governo Italiano (2021), Italia Domani. Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza, 23/IV/2021, https://www.governo.it/sites/governo.it/files/PNRR.pdf.

13 Governo Italiano (2021), Comunicato Stampa del Consiglio dei Ministri, Presidenza Consiglio dei Ministri, nr 21, 28/V/2021.

14 Sergio Fabbrini (2021), ‘La Governance del PNRR e il Governo d’Italia’, Il Sole 24 Ore, 7/VI/2021.

15 See notes 4 & 10.

16 T. Roldan et al. (2021), Reformas, gobernanza y capital humano: las grandes debilidades del Plan de Recuperación, Esade.

17 See note 13.

18 BrusselsReport.eu‘Spain’s spending of EU Recovery Funds threatens to turn into a top-down exercise’, 15/IV/2021.

19 Enrique Feás (2021), ‘Lo que sabemos, y lo que no del Plan de Recuperacion’ Blog NewDeal, 2/II/2021,

20 See note 13.

21 La Moncloa (2021), Web Informativa sobre el Plan de Recuperacion, Transformacion y Resilencia, 29/VII/2021.

22 See note 15.

23 Rebeca Gimeno (2021), ‘Manuel A. Hidalgo, economista: “los Fondos Europeos no van de lograr financiacion extra sino de cambiar la economia’, NIUS. 23/I/2021.

24 See note 13.

25 See note 13.

26 Francesco Papadia (2021), ‘Recovery Fund’, SkyVideo, 23/IV/2021, 10:35.

27 Luis Garicano (2021), ‘El Plan de Recuperacion de Espana: valoracion de reformas e inversiones’

28 See note 15.

29 Lidia Baratta (2021), ‘Poche Riforme: Il Recovery Plan è una Fumosa Lista della Spesa che la Commissione UE Respingerà’, Linkiesta, 13/I/2021.

30 La Moncloa (2021), Referencia del Consejo de Ministros, 23/III/2021.

31 See note 16.

32 See note 13.

33 Enrico Deidda Gagliardo (Professor at the Università di Ferrara) in discussion with Gianni Dominici, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dObkKnAcG0A.

34 CERVAP. ‘Forum PA 2021: Gli Interventi del Prof. Enrico Deidda Gagliardo”, 1/07/2021.

35 El Pais ‘Fondos europeos: un reto de gestión colosal’, 14/XI/2020.

36 For the risks that acknowledged in the Spanish case, see note 21.

37 See note 24.

38 See note 6.

39 See notes 4 & 10.

40 Juan Pablo Riesgo (2021), EY Insights, ESADE, ‘Enfocando NextGenerationEU hacia la inversion en capital humano’, 24/III/2021.

41 See note 13.