Theme

After evaluating the EU’s North-Korea strategy, this paper argues that Critical Engagement should be substituted by a more proactive approach that would better serve Brussel’s interests in the region.

Summary

This study critically evaluates the EU’s North Korea strategy and argues that Critical Engagement is an outdated and ineffective strategy for pursuing Brussels’ interests in the region. As Critical Engagement has failed on both the level of its stated objectives and strategically, a sober debate on a new North-Korea strategy is required, one which allows for a longer-term strategic planning of the EU’s relations with the Korean peninsula in general and North Korea in particular and put the EU in a stronger position to proactively contribute to the maintenance of peace and stability. This new strategy should specifically target those dimensions of the conflict to which Europe can make a tangible contribution, identify corresponding initiatives which better help to the achievement of the EU’s main objectives vis-à-vis the Korean peninsula, reflect the different roles of and contributions that can be made by the various actor(s) within the EU, and specify at which stage of the conflict (resolution) those initiatives are expected to be put into practice.

Analysis

Introduction

For well over two decades now, the EU’s policy on North Korea (DPRK) is based on a strategy known as Critical Engagement. In a nutshell, the strategy is that Europe is willing to use both carrot and stick, incentives and pressure in its relations with North Korea. In fact, since its inception in 1995, the EU’s Critical Engagement strategy underwent a number of changes reflecting these different policy options, from a more active engagement in the mid-1990s to the early 2000s and a more critical variant since 2013 to the current policy of active pressure. The primary goals of the Critical Engagement strategy are to support a lasting reduction of tension on the Korean peninsula and in the region, to uphold the international non-proliferation regime and to improve the situation of human rights in the DPRK. This paper’s main argument is fairly simple: Critical Engagement is an outdated and ineffective ‘strategy’ for pursuing the EU’s interest in the region as it has failed on two crucial levels: first, with tensions on the Korean peninsula hardly having decreased, North Korea’s nuclear and missile programmes significantly advanced, the non-proliferation regime noticeably weakened and the human rights situation in North Korea unimproved, the goals of the EU’s Critical Engagement strategy have not been achieved, to put it mildly. Secondly, with the EU’s active pressure policies since 2013-14, expressed most vividly by a focus on restrictive measures and a halt in official dialogue, it has become apparent that an overemphasis on the first component of the Critical Engagement strategy leads to a diminished role for the EU, bordering on irrelevancy. Against this background it will be important for Europe to give the nuclear conflict the high priority and political support it deserves, to formulate an independent strategy and resulting policies based on Europe’s interests, and to clearly articulate and pursue this policy vis-à-vis the relevant regional actors.

Background: the development of the EU’s strategy vis-à-vis North Korea at a glance

As mentioned, officially the EU’s relations with the DPRK are based on an approach known as Critical Engagement. That is, Europe is willing to use both carrot and stick, incentives and pressure in its relations with North Korea. Its primary goals are to support a lasting reduction of US on the Korean peninsula and in the region, to uphold the international non-proliferation regime and to improve the human-rights situation in the DPRK. While cooperation and engagement are considered a central element of the strategy, in more recent years the EU has placed its focus clearly on the first element of the Critical Engagement strategy. In fact, since 2013-14, sanctions constitute the main element of the EU’s strategy vis-à-vis North Korea, while its engagement initiatives have been significantly reduced. This has led some observers to assess that the EU’s North Korea strategy has actually undergone three distinct phases: active engagement (1995-2002), critical engagement (2002-13) and active pressure (since 2013-14).1

The current emphasis on actively pressuring the DPRK contrasts with the EU’s earlier strategy, which, at times, saw a considerable degree of engagement, initially through various forms of assistance to the DPRK. According to information provided by the European Commission (2019), the EU ‘has responded to humanitarian needs in North Korea since 1995’. Explicitly designated as a contribution to regional stability, between 1995 and 2002 alone the EU provided North Korea with food aid and structural food security assistance, humanitarian assistance and technical assistance roughly totalling €400 million –excluding further bilateral assistance initiatives by individual EU member states–.2 In the 1990s Brussels started to establish initiatives with the DPRK that moved beyond mere economic assistance and aid. For instance, acknowledging the role the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO) could play to maintain peace and stability on the Korean peninsula, the EU became a member of the organisation’s Executive Board in September 1997. In 1998 the EU and North Korea established a political dialogue at the Senior Official level, with a total of 14 meetings until its suspension in 2015. In the early 2000s, as both the EU and most of its member states had established diplomatic relations with Pyongyang, Europe expanded its economic support for North Korea, for instance by opening the European market to North Korea and providing technical support for the structural development of its economy. The EU’s proactive initiatives in the early 2000s must also be placed in the context of the engagement policy of the then South-Korean President Kim Dae-jung, who called upon EU members to support his new approach to North Korea. A major event in North Korean-EU relations was the visit of the so-called EU Troika to Pyongyang in May 2001. During the visit of Swedish Prime Minister Göran Persson, EU Commissioner Chris Patten and High Representative for Common and Foreign Security Policy Javier Solana, the delegation managed to receive a commitment from Kim Jong-il to honour the inter-Korean Joint Declaration signed at the June 2000 summit and to maintain a moratorium on missile testing until at least 2003. The May 2001 visit was significant, for the US was, at that time, just in the process of ‘reviewing’ its policy towards North Korea through the so-called Perry Process. In fact, some observers argued that the EU’s May 2001 visit was to be understood as a sign of a possible beginning of a more independent EU foreign policy vis-à-vis the Korean peninsula.3 However, the hopes for a more independent EU policy and/or a more immediate engagement of Brussels in the security relations in the (North-) East Asian region were quickly dashed following the advent of what became known as the ‘second nuclear crisis’ on the Korean peninsula in 2002.

With the emergence of the second nuclear crisis on the Korean peninsula, the trajectory of EU-North Korea relations changed abruptly, resulting in a shift in the EU’s strategy from ‘active engagement’ to a more conditional engagement. For example, the EU withdrew its support for programmes designed to bolster North Korea’s economy, terminated its support for the KEDO project in light-water reactor development and cancelled its plan to provide technical support to lay the foundations for economic development. In addition, the EU suspended a plan to support further opening its market to North Korean products and both issued a human-rights resolution against the DPRK at the United Nations in 2003 and also approved resolutions against North Korea at the EU Parliament. Overall, however, between 2002-03 and 2013 the EU attempted to balance such increasing political pressure with continued political engagement. As such, Brussels sustained the political dialogue with Pyongyang and, regardless of North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile provocations, continued to provide food and humanitarian aid to Pyongyang. During North Korea’s food crisis of 2011, in particular, the EU provided €10 million as emergency assistance,4 while limited contributions to humanitarian aid funding continued to 2013.

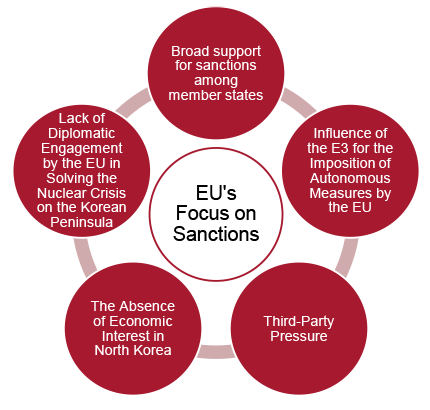

With the escalation of nuclear and missile testing activities by North Korea following the inauguration of Kim Jong-un in 2011, in line with a significant aggravation of tension between North Korea and the US, the EU adopted a strategy of ‘active pressure’, characterised by a comprehensive support of both UN sanctions and autonomous restrictive measures as well as the suspension of official dialogue tracks. In 2015 the EU furthermore suspended its official dialogue with North Korea, leaving by and large some informal dialogue channels, the diplomatic representations of EU member states in Pyongyang as well as a few engagement initiatives by individual EU member states. The EU’s passive stance and focus on sanctions is explained by a number of interdependent explanatory factors that are summarised in Figure 1.5

Understanding the motives driving the EU’s sanctions policy is crucial to evaluate both the reasons for Brussels’ current North Korea strategy as well as the possibility of any policy change in the future.

The failure(s) of Critical Engagement

The Critical Engagement strategy formed the basis for the EU’s North-Korea policy for almost a quarter of a century. Above all, advocates praise the approach for its flexibility, as it is said to avoid the restrictions and escalation risks associated with a policy based on conditions and linkages, and makes it possible for Europe to apply pressure (eg, through sanctions) and offer incentives (eg, through humanitarian aid provision, economic cooperation or dialogue) vis-à-vis North Korea in a flexible manner. These different policies and policy options of the Critical Engagement strategy are reflected by the several phases of EU-North Korea relations discussed above –from a more active engagement in the mid-1990s to the early 2000s and a more Critical Engagement variant until 2013 to the current policy of active pressure–. While Europe’s Critical Engagement policy was a promising starting point for a coherent and sustainable foreign policy towards the DPRK, the past 25 years have shown that it has not promoted a comprehensive European strategy for the Korean peninsula in general and North Korea in particular. The strategy proved to be highly dependent on political circumstances and failed both at the level of its strategic objectives and of its strategic calculation, thereby further weakening Europe’s role in East-Asian security affairs.

First, the Critical Engagement approach has failed to achieve its stated objectives: to support a lasting reduction of tension on the Korean peninsula and in the region through a denuclearised North Korea, to uphold the international non-proliferation regime and to improve the situation of human rights in the DPRK.6 With North Korea’s nuclear and missile programmes significantly advanced and tension on the Korean peninsula hardly decreasing, the non-proliferation regime noticeably weakened and the human rights situation in North Korea not improving, the goals of the EU’s Critical Engagement strategy have not been achieved, to put it mildly. To argue that Critical Engagement has failed to achieve its stated objectives is not, of course, to say that Europe pursued the wrong objectives, but rather that it is the wrong methodology to achieve those objectives.

Secondly, Brussels’ Critical Engagement strategy also failed on a strategic level, for the era of active pressure since 2013-14 has had distinctly negative strategic consequences for the EU as well. That is, the strategy of active pressure promotes a passive and reactive North Korea policy –expressed most vividly by a singular focus on restrictive measures and a halt to official dialogue– that promoted an even more diminished EU role in East-Asian security affairs, bordering on irrelevance. In line with the EU’s active pressure strategy against North Korea and the subsequent strengthening of the sanctions regime, Brussels simultaneously and dramatically decreased its political engagement with North Korea, leaving only some informal dialogue channels and individual engagement initiatives by specific member states. What’s more, the EU fully linked tangible progress to the nuclear issue, even to the point of demanding ‘complete, verifiable and irreversible dismantlement’ (CVID), to the development of other aspects of its relationship with the DPRK. That is, the EU took a step forward in the one area in which it virtually has no diplomatic clout, making it a precondition for developing other aspects of its relationship with North Korea. As such, the EU’s disengagement promoted a further decrease in diplomatic influence in security affairs in East Asia and a further diminishing of its role in security affairs in North-East Asia.

Moving beyond Critical Engagement: initial steps towards a new EU North-Korea strategy

North-East Asia is in many ways a challenging terrain for the EU, which can only expect to play a ‘secondary’ role to the region’s dominant players, and calling for a new North-Korea strategy is, of course, not to suggest such a reformulation could or should lead Brussels to seek a role of strategic influence similar to the region’s primary players –that is neither realistic and nor would it be helpful–. This does not, however, condemn Brussels to be purely reactive and passive. Rather, if a higher priority is given to security affairs on the Korean peninsula in both Brussels and the member states and any new initiative is backed by the necessary political and diplomatic weight and priority, then the EU can very well contribute to and find its role and place in regional security affairs.7 The EU’s current North Korea strategy, however, is an outdated and ineffective instrument for pursuing Brussel’s interests in the region and leaving a substantial impact on the ground. In view of this context, Brussels should start a sober debate on a new North-Korea strategy. The formulation of a new strategy, which requires an intensive consultation process both within the EU and with its regional partners in order to consider the different views of the wide range of European and North-East Asian stakeholders, should allow for a longer-term strategic planning of the EU’s relations with the Korean peninsula in general and North Korea in particular and put the EU in a stronger position to contribute proactively to the maintenance of peace and stability in the area. As such, a new North-Korea strategy for the EU must:

- Target those dimensions and areas of the conflict in which Europe can make a meaningful contribution.

- Identify corresponding initiatives that better contribute to the realisation of the EU’s main objectives in the Korean peninsula.

- Reflect the different roles of and contributions that can be made by the various actor(s) within the EU.

- Specify at which stage of the conflict (resolution) those initiatives are expected to be put into practice.

The nuclear issue on the Korean peninsula is inherently linked to and comprises a number of interrelated conflict dimensions, ranging from the security and the military to the political and the diplomatic and the economic and socio-cultural. Specifying in detail the dimensions of the conflict(s) to which each EU actor can make what contributions and when, is crucial to ensure long-term political support. While the EU’s immediate influence in the ‘high politics’ sphere is limited, there are nonetheless useful contributions that different European actors can make at different stages of the conflict. Specifically, Europe should target two particular strategic areas:

- As a main focus: fostering dialogue both between EU (member states) and North Korea and between the conflict’s primary actors.

- As a secondary focus: prepare specific contributions to implement eventual agreements.

Focusing Europe’s North-Korea strategy on such realistic and useful initiatives is to actually build on the genuine strengths of Europe in the conflict on the Korean peninsula. How these strengths can be utilised, and what kind of valuable contribution Europe can make in the conflict is exemplified by Sweden, which time and again has acted as a facilitator of dialogue with the DPRK. For example, in parallel to its own diplomatic outreach to North Korea (such as repeated visits by officials from the North-Korean Foreign Ministry), in 2019 Sweden hosted both working-level meetings between North Korea and the US, bringing together high-ranking officials from these countries in January and October. Moreover, at times when official dialogue with North Korea was absent at the government level, especially in 2017, think tanks and academic institutions in several European countries such as Sweden, Norway, Finland and Spain have already created important spaces for discreet discussions between North Korean and Western experts and (former) government representatives on the Track 1.5 level. These examples show the important contributions that individual EU member states can make if the necessary political will and diplomatic weight is placed behind them. In this context, the EU should immediately resume dialogue with the DPRK, which offers a comparatively rare opportunity to discuss directly with the country the issues that Europe considers particularly important within the framework of an institutionalised dialogue.8 In order to get closer to the real decision-makers in North Korea, Brussels should consider the possibility of upgrading the dialogue to a higher diplomatic level. An institutionalised channel of dialogue between the EU and the DPRK could help to better understand North Korean motives and objectives, while at the same time improving the relationship of trust between the two sides –which would have a positive impact whether or not the ongoing negotiations between North Korea and the US, as well as between the two Koreas, are successful–. Besides the facilitation of dialogue, Europe’s contributions to the high-politics dimension of the conflict will most likely come in the form of specific support for the implementation of an eventual agreement. Hence, preparations in Europe for any possible scenario, including a political settlement of the nuclear issue, will be crucial. In that case, the EU can very well play a role in the implementation process, especially regarding the technical aspects of an eventual denuclearisation process, for instance by helping to shape a strong monitoring and verification mechanism or contributing to the removal of North Korea’s nuclear infrastructure, among others.

While Europe’s immediate influence on the high politics sphere of the nuclear issue is limited, there are numerous initiatives the EU and/or its member states might foster in the ‘low politics’ sphere. In particular, Europe should target two specific strategic focus areas within the ‘low politics’ sphere:

- As a main focus: economic contributions, both for leverage and as a contribution.

- As a secondary focus: foster people-to-people contacts and maximise international exposure.

Without doubt, the EU can make valuable contributions in the field of the economy. For instance, given the changing internal and external context, any serious nuclear negotiation with North Korea in the future will require a new approach to providing inducements that will lead to more successful outcomes than previous negotiations. The high priority now being given to economic development by the Kim Jong-un leadership provides a number of potentially attractive opportunities and measures to encourage and support a new nuclear negotiation. Elevating the economic dimension of the negotiations to a higher standard than in the past is well worth exploring. In fact, it may be essential for achieving the political and security objectives of the US and in bringing North Korea closer to integration in the international community in ways that will improve longer-term stability on the Korean peninsula. At a later stage of the conflict solution-process, the rebuilding of key sectors of North Korea’s economy, such as infrastructure and energy, will be of crucial importance. Besides economic and/or humanitarian contributions, a secondary focus should be placed on fostering people-to-people contacts and maximising the international exposure of North Korea, for instance by supporting academic exchanges.

Conclusions

Critical Engagement has been the EU’s official North-Korea policy for well over two decades now. This paper has aimed at critically reflecting on the strategy and argued that Critical Engagement did not promote a comprehensive European strategy for the Korean peninsula in general and North Korea in particular. The strategy has proved to be highly dependent on political circumstances and has failed both on the level of its strategic objectives and of its strategic calculation, thereby further weakening Europe’s role in East-Asian security affairs. Against this background it is imperative to initiate a sober debate on the outlines of a new strategic approach, one that puts the EU in a stronger position to proactively contribute to the maintenance of peace and stability on the Korean peninsula. It is proposed that this strategy should specifically target those dimensions of the conflict to which Europe can make a tangible contribution, identify corresponding initiatives which better contribute to the achievement of the EU’s main objectives in the region, reflecting the different roles of and contributions that can be made by the various actor(s) within the EU, and specifically at which stage of the conflict (resolution) those initiatives are expected to be put into practice. This, of course, requires the EU and its member states to finally give the challenges on the Korean peninsula the high priority in Europe that they deserve.

Dr. Eric J. Ballbach

Director of the North Korea and International Security research unit at the Institute of Korean Studies, Freie Universität Berlin, and Korea Foundation Visiting Fellow at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs | @EricBallbach

1 This classification was first made by Professor Ko Sangtu in a Keynote Address at the EIAS Briefing Seminar in October 2017. See http://www.eias.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/EIAS_Event_Report_Quo_Vadis_North Korea_20.10.2017-2.pdf.

2 Axel Berkofsky (2003), ‘The EU’s policy towards the DPRK – Engagement or standstill?’, Briefing Paper, European Institute for Asian Studies (EIAS), Brussels.

3 Rüdiger Frank (2002), ‘EU-North Korean relations: no efforts without reasons’, International Journal of Korean Unification Studies, vol. 11, nr 2, p. 87-119.

4 European Commission (2011), ‘The European Commission will give emergency food aid to North Korea’, European Commission, Press release, 4/VII/2011.

5 Eric J. Ballbach (2019), ‘The EU’s sanctions regime against North Korea’, SWP Study (forthcoming).

6 European External Action Service, ‘The DPRK and the EU’.

7 Rhetorically, the EU and many of its member states frequently stress their readiness for a more proactive European role on the Korean peninsula. In reality, however, North-East Asia and particularly the Korean peninsula have always been a lower priority area for the EU, given both the greater influence of the regional powers and more urgent developments in its immediate neighbourhood. However, while Europe’s immediate influence in security affairs on the Korean peninsula is not vital, its strategic interests are important. The reasons why North Korea matters for Europe include, among others, its threat to the nuclear non-proliferation regime, the implications of North Korea’s nuclear and missile programmes to regional peace and stability, the sale of weapons systems and human rights considerations. Given these risks and implications, it is important to give the challenges on the Korean peninsula the high priority in Europe they deserve.

8 See also Mario Esteban (2019), ‘The EU’s role in stabilising the Korean Peninsula’, Working Paper, Elcano Royal Institute, p. 37.