Theme

This analysis argues that Narendra Modi will have to deliver much bolder reforms in his second term in order to allow India to reach its potential turning its rising working age population into a demographic dividend.

Summary

Prime Minister Modi shows a mix record in fulfilling his promises on economic reform during his first term. He has made some progress in attracting capital and reforming the banking sector, but, much of the work is left unfinished as India still does not attract enough FDI in manufacturing to absorb its labor force. Moreover, India needs to also increase its savings rate to boost infrastructure investment. Both require Modi to deliver much bolder reforms in his second term that is certainly a strong leap from where it is today. That said, India is the only country comparable to that of China and any significant progress in India will be globally consequential.

Analysis

Official results will not be published until 23 May , but Narendra Modi and his incumbent coalition government are set to retain power as suggested by a few exit polls after India concluded the final phase of its six-week ballot. The projections indicate that the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) will secure most seats in the Lok Sabha –the lower house of India’s parliament–. Meanwhile, exit polls are divided as to whether the BJP can win a parliamentary majority on its own, with several predicting that it will lose seats compared with its 2014 landslide victory.

While exit polls have a record of being inaccurate in past elections, the huge difference between the NDA’s projected seats versus the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) led by the opposition Congress means that each of the exit polls should be extremely unreliable for the case of an NDA loss. As the election is widely seen as a referendum on Modi’s leadership over the past five years, his victory would indicate that the public is generally willing to give him a second term to complete unfinished tasks, such as reducing the high unemployment rate.

That said, even with the recent economic slowdown, India still boasts Asia’s fastest-growing economy in 2018. But beneath the veneer of impressive GDP expansion, unease about India’s economic model clearly tempers enthusiasm. There is no doubt that the slowdown in the Indian economy casts a shadow over Modi’s second term and whether this time things will be different, for instance as to whether he will finally push through key economic promises to provide India with much-needed investment and jobs.

Growth is particularly important to India not only because of its need to converge on account of its low GDP per capita but also to pressure on employment creation on the back of its rapidly growing population. In fact, India struggles to generate enough formal jobs and lacks capital to invest in infrastructure to absorb its existing excess labour supply.

To assess what is at stake in Modi’s second term, this paper analyses India from two perspectives: (1) the progress the Modi government has so far made on key pillars of his pledges since coming to power in 2014 ; and (2) the scale of reforms that needed for India to reach its potential. For the latter, we use China as a comparison based on similar population size and, possibly, even –in many ways– global ambition.

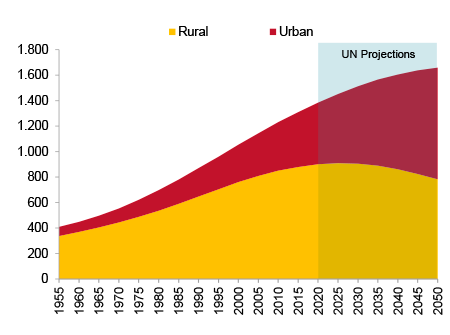

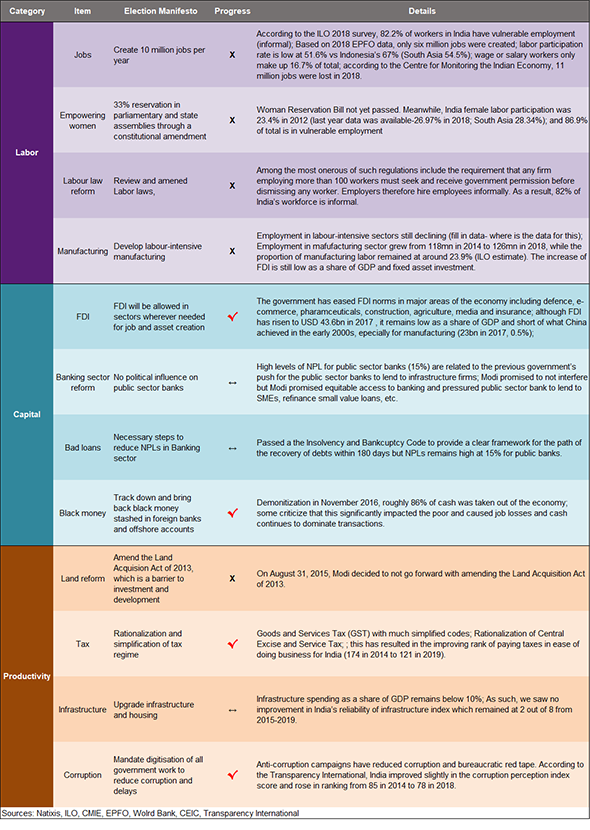

(1) Modi has made progress but far from enough compared to what India needs

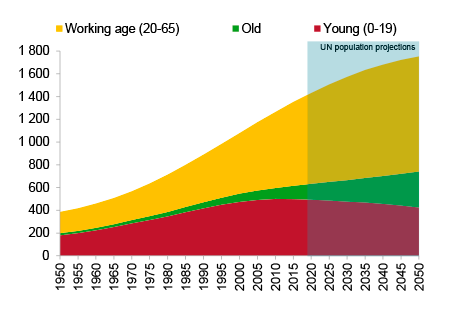

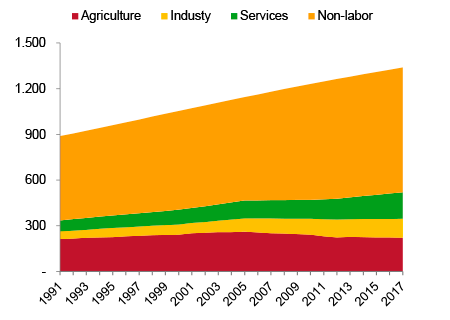

We have analysed Modi’s pledges within the framework of the Solow growth model, which looks at three output/production factors: labour, capital and productivity (soft infrastructure reforms). India does not have a challenge as regards the supply of labour, in contrast to countries in East Asia, since its working-age population is expected to expand rapidly, so much so that it needs to create millions of jobs per year in the next decade to absorb all its incoming labour (see Figure 1). Beyond its employment needs, India struggles in regard to total factor productivity, which requires capital to absorb existing and incoming labour into more productive sectors as well as reforms to reduce red tape. Reforms are required in all three aspects of the Solow growth model to escape from its current low middle-income trap.

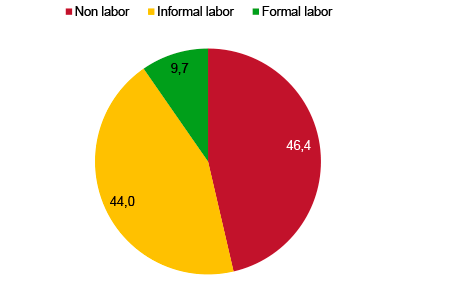

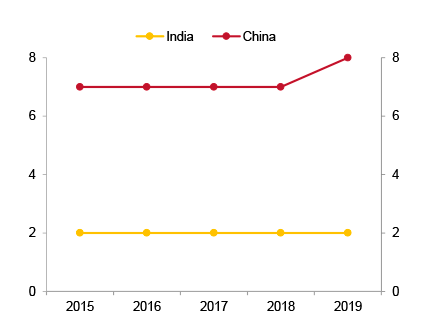

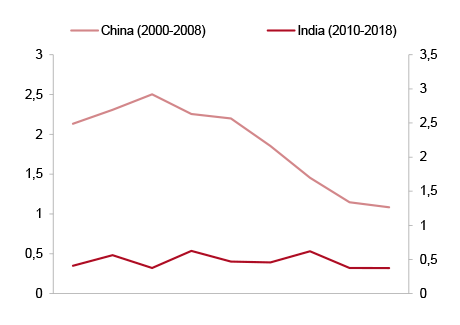

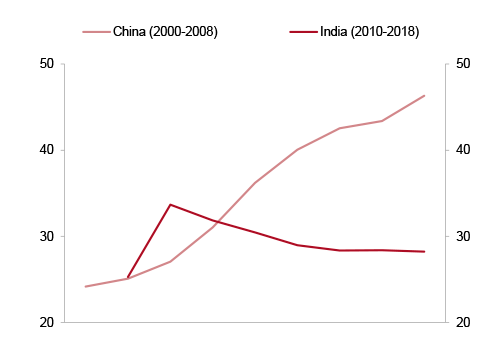

India currently has a low labour participation rate, especially compared with China (see Figure 2). Worse still, within its employment population, the vast majority are still stuck in informal sectors, which equates to low total factor productivity. For China, informal employment takes up a significantly lower proportion of total. The situation can only get worse for India unless many more jobs are created.

These challenges are well understood within India’s academic and political circles and have been sources of how to address the ills of India’s under-performance despite its great demographic potential. Modi and his BJP have made pledges on the country’s key economic challenges.

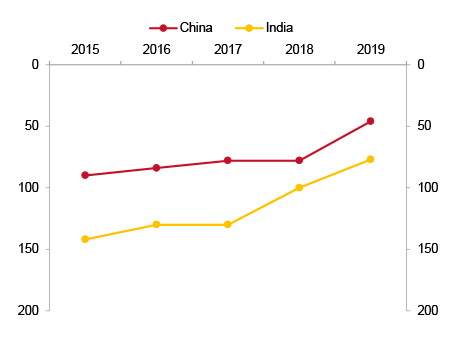

First, starting with the positive progress Modi has made since 2014, mainly pertaining to capital, while he underperforms on his labour and productivity promises. Capital is obviously important as the infrastructure deficit is a clear bottleneck to create more jobs. Regarding capital, there are two obvious ways to increase it: foreign capital and public investment. As for the former, Modi has tried to liberalise both FDI and portfolio with mixed results. Within his ‘Make in India’ campaign, a few measures to open up some sectors to foreign competition have been taken, which have helped increase FDI into India (see Figures 15 and 6). That said, it is still significantly less than what is really needed to increase demand for workers, particularly in the manufacturing sector, which only comprises a small percentage of GDP even compared to China’s in the early 2000s (Figure 11).

Moreover, Modi has backtracked on some of his reforms, particularly in opening up e-commerce given the backlash from small- and medium-sized retailers who make up a large part of the voting population. For instance, the recently announced e-commerce rule to cap the inventory sourcing of online retailers from a same supplier –many of them being stakeholders of these online retailers– has hurt Amazon to the benefit of domestic players and raised questions about the commitment and consistency of India’s foreign investment policy.

In addition to a relatively timid opening up to inward FDI, his government has also further liberalised portfolio investment. In particular, the quota for foreign investment in Indian government bonds has gradually been lifted. As regards public investment, Modi has tried to increase the tax base by introducing goods and services taxes (GST) that aim to harmonise existing taxes with much more simplified codes. This has resulted in improved ease-of-paying-taxes and ease-of-doing-business rankings for India (Figures 3 and 4).

Regarding management of capital, particularly banking sector reform, the Modi government approved an Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code to provide a clear framework for recovering debts. That said, the non-performing loans (NLP) ratio remains high for public banks. Modi also demonetised the economy in the hope of tracking down and bringing back black money stashed away in foreign banks and offshore accounts. This removed the majority of currency from the system but faced a backlash in that it disproportionately hurt small- and medium-sized enterprises and resulted in job losses. Based on data from the Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy, both GST and demonetisation caused massive job losses in 2018.

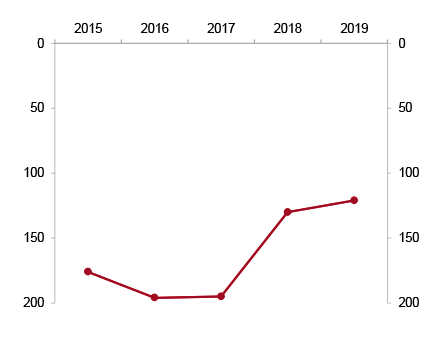

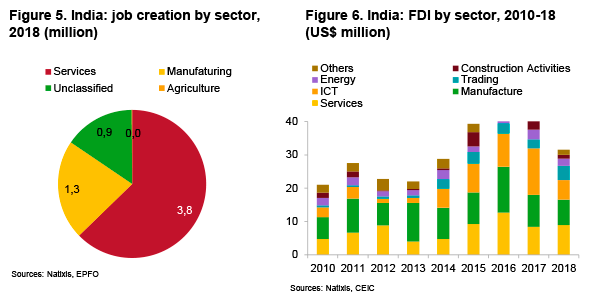

While Modi has made progress on whatever concerns capital as a factor of production, he has clearly fallen short on both labour and productivity reforms. On the labour side, his government has discontinued the collection of meaningful comprehensive labour data, but our estimate is that the Indian economy is far from delivering much-needed jobs for the its massive labour supply. Modi promised 10 million new jobs per year but new payroll records from EPFO point to a huge gap in jobs created in 2018 (Figure 5). Moreover, the ILO estimates for informal labour have worsened over the years as the size of vulnerable employment has risen and that is in addition to half of the working-age population being idle.

The weakness of the job scenario is supported by incorporating FDI inflows into the manufacturing sector. The Make in India slogan primarily attracts services and information & communication technology while not enough manufacturing FDI (Figure 6). In other words, it is a mere drop in the bucket of what is needed for India to become self-sufficient in manufacturing, let alone to becoming a manufacturing centre of the world. For example, India exported a comparable volume of manufacturing goods in 2018 as Vietnam, a country significantly smaller in size. It does not help that Modi’s pledge to improve infrastructure is held back by limited public funding and a banking sector saddled with bad loans and dominated by state-owned banks. In fact, the quality of India’s infrastructure has seen little improvement over the past five years (Figure 7). Moreover, India’s infrastructure spending has been stuck in low gear since 2014 too (Figure 8).

One of the key challenges to investment and development in India is its restrictive land and labour laws. Modi had promised to repeal the Amend the Land Acquisition Act of 2013, which is a barrier to investment and development, but on 31 August 2015 Modi decided not to go forward. Modi also promised to review and amend Labour laws, which are onerous, but has not done so. For instance, India requires any firm employing more than 100 workers to seek and receive government permission before dismissing any employee. Employers therefore hire informally to get around the law and, as a result, most of India’s workforce is informal.

In short, while the Modi government has made progress in attracting capital, its pace has been agonisingly slow for what is needed to allow India to turn its rising working-age population into a demographic dividend. The following section discusses what is needed for India to do so.

(2) What is needed to take India to the next level: savings and investment

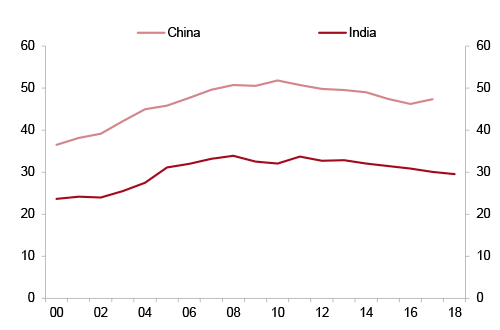

The only country comparable to India is China due to their massive sub-continental population and their geographical size. For India, the road forward is clear: it needs to raise its capital stock per worker, but the debate is how to do so. China’s experience in the early 2000s may prove to be an important lesson for India. There are two key differentiating factors between the two countries: (1) the rapid urbanisation of China’s rural population by moving farmers into factories by attracting FDI in manufacturing to capitalise on its comparative advantage in labour; and (2) the rise in China’s savings rate to finance necessary infrastructure projects and to develop sectors needed for industrialisation.

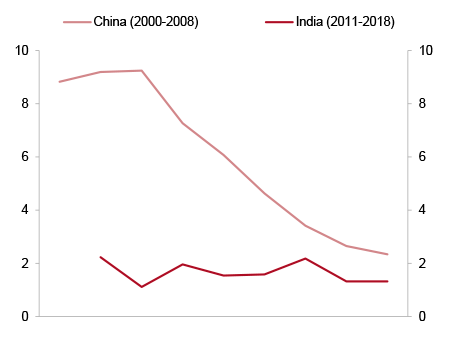

The previous section showed that the key challenges to India are well understood, such as labour and land reforms. That said, the scale of progress needed is not often discussed. Although India is the only country that can absorb the labour-intensive manufacturing that is increasingly uncompetitive in China, it only attracts as much manufacturing FDI as Vietnam, a country a tenth of its size.

India currently attracts small amounts of manufacturing FDI, having remained at the same level over the past eight years. If compared to China when it joined the WTO in 2001, India’s level is too low to attract much-needed capital, particularly the kind of capital that demands large numbers of workers. As a share of fixed asset investment (FAI), manufacturing FDI in India also lagged behind. As an aggregate, India has not done so badly, but, as mentioned, most is not in much-needed manufacturing, with the result that India needs to absorb much more capital from the rest of the world than it currently does to boost labour demand in manufacturing.

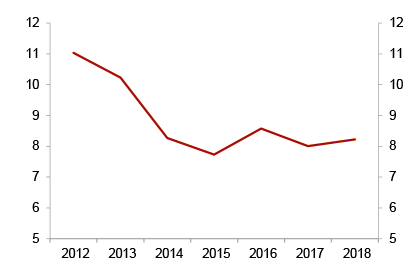

Beyond using its labour surplus advantage to attract labour-intensive manufacturing, India also needs to increase its savings rate to be able to fund much-needed infrastructure development. Such a gap is particularly noticeable when compared to China in the early 2000s. The country’s persistent current account deficit makes it vulnerable to volatile capital flows, another key reason why it needs to attract more FDI and also raise the savings rate. Because of this capital deficit, the Indian government cannot engage in public-led investment without significantly raising the deficit. The previous administration forced the state-owned bank to lend to infrastructure firms and caused a large increase in NPLs. Since then, investment in infrastructure has declined. Our assessment of India’s significantly lower investment than China means there is much scope to increase.

Conclusions

Our analysis of Modi’s progress report shows that he has made some progress in attracting capital and reforming the banking sector. That said, much of the work remains unfinished as India still does not attract enough FDI in manufacturing to absorb its labour force. Indeed, India needs to attract 2% more of GDP than it currently does. This should help it leverage its excess labour supply to absorb much-needed capital from the rest of the world and close the financing gap. Moreover, India also needs to increase its savings rate to boost infrastructure investment. Both require Modi to deliver much bolder reforms in his second term, in what should be a significant leap from where it is today. India is the only country comparable to China and any significant progress it makes will have global consequences.

Alicia García Herrero

Senior Research Fellow, Elcano Royal Institute | @Aligarciaherrer

Trinh Nguyen

Senior Economist Natixis | @Trinhomics