Theme

In October 2023 Brussels hosted the inauguralGlobal Gateway Forum, a high-level conference devoted exclusively to the initiative of the same name and the first to be held since its launch two years ago. This provides an ideal opportunity to reflect on the path that has led to this point and to ponder the nature of the initiative and its potential, with particular emphasis on its relevance to Latin America and the Caribbean.

Summary

The Global Gateway initiative is aimed at channelling, multiplying and raising the profile of the EU’s public and private resources devoted to development aid. It is a geopolitical strategy that seeks to underpin the Union’s alliances with its partners in priority areas, such as infrastructure and connectivity, the green transition and healthcare. Its implementation fundamentally rests first on the Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument, also known as Global Europe, and secondly on the Team Europe approach as a modus operandi. This initiative promotes and publicises the added value of European cooperation, which is committed to transparency, dialogue, sustainability, human rights and democratic values. In this regard, Latin America and the Caribbean region can potentially claim the status of a privileged partner.

Analysis

(1) What is the Global Gateway?

The initiative launched two years ago by the European Commission under the leadership of its President, Ursula von der Leyen, seeks to channel, multiply and raise the profile of the resources –public and private– earmarked by the EU and its member states for development aid sent to third countries, especially in the areas of infrastructure, connectivity, the green transition, healthcare, education and research. It thus constitutes a geopolitical attempt to enhance and underpin the visibility of European cooperation, and to ensure closer relations with the EU’s partners in developing their areas of greatest priority.

The Global Gateway acts as an umbrella for European development aid. It sets out strategic guidelines for cooperation, as well as for European foreign investment, with the prospect of mobilising €300 billion between 2021 and 2027, combining resources from the EU’s own budget with additional sources from public and private funding.

(2) Implementation of the Global Gateway

The implementation of the Global Gateway rests fundamentally on two pillars: (a) the Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI), also known as Global Europe; and (b) the Team Europe approach.

(2.1) Global Europe/NDICI

Global Europe/NDICI, approved in June 2021, is the European Commission’s instrument for scheduling, financing and implementing its development aid during the 2021-27 financial cycle. This is thus the executive arm of the Global Gateway.[1]

Global Europe/NDICI has been allocated a budget of €79.5 billion for the 2021-27 period, which in turn is funded by the EU’s Community Budget supplied by contributions from the member states. The budget is divided into geographic programmes, thematic programmes, a rapid response mechanism and a tranche reserved for emerging challenges and unforeseen situations. This instrument thus sets the priorities and the budgetary division on the basis of which the pertinent agreements, both pluriannual and annual, are subsequently signed with partner countries (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Global Europe/NDICI budget allocations 2021-27 (1)

| Budget (€ bn) | |

|---|---|

| Geographic programmes | 60.4 |

| Neighbourhood | 19.3 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 29.2 |

| Asia and the Pacific | 8.5 |

| The Americas and the Caribbean | 3.4 |

| Thematic programmes | 6.4 |

| Human rights and democracy | 1.4 |

| Civil society organisations | 1.4 |

| Peace, stability and conflict prevention | 0.9 |

| Global challenges | 2.7 |

| Rapid response mechanism | 3.2 |

| Unallocated funds | 9.5 |

| TOTAL | 79.5 |

Source: European Commission.

The implementation of Global Europe/NDICI relies on various tools. Notable among these is the European Fund for Sustainable Development Plus (EFSD+), which constitutes its funding arm. The EFSD+ supplies the financial resources to: (a) support blended financing operations; (b) offer budgetary guarantees to incentivise the deployment of investments; (c) fund technical assistance; and (d), to a lesser extent, fund other forms of support, such as the concession of direct grants. The budgetary guarantees have the backing of an External Action Guarantee capable of guaranteeing up to €130 billion, which will be drawn upon should it prove necessary.

Within Global Europe/NDICI, the EFSD+ has the capacity to supply funding of €53.5 billion, which comes from the instrument’s geographic programme. Of the €53.5 billion channelled through the EFSD+, €40 billion can be used to mobilise private resources for investment through blended financing and budgetary guarantees. The remaining €13.5 billion is earmarked for technical assistance and other forms of support such as grants.

The difference between Global Europe/NDICI’s total budget (€79.5 billion) and funding through the EFSD+ (€53.5 billion) is channelled through other budget implementation tools that do not necessarily imply the same types of direct spending, such as technical cooperation and support measures for technical assistance and monitoring activities.

It is envisaged that Global Gateway’s goal of making €300 billion available to its partners will be achieved using three pathways:

(a) Based on the €40 billion at the disposal of the EFSD+ for blended financing and guarantees, it is expected to mobilise up to €135 billion. This would translate into an expected multiplier factor of 3.4. Achieving this target depends on guarantees and blended financing incentivising the private sector and financial institutions (including financial institutions specialising in development).

(b) Mobilising as much as an additional €145 billion through the European financing institutions –principally the European Investment Bank (EIB), which grants loans to companies, governments and financial institutions and oversees an investment portfolio of more than €390 billion, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD)– and through member states’ development aid programmes. Notable among the latter are the German Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau, which in 2022 alone allocated €11 billion in new funding for the development of emerging and developing countries; the French AFD group, which in 2022 agreed €12.3 billion in new funding for third country development aid; the Italian Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (CDP); and the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID). Unlike public investment, private investment would be incentivised on the basis of funds initially provided by European development agencies themselves and those of member states, rather than coming from the community budget as is the case with the EFSD+.

(c) Lastly, it is envisaged that Global Europe/NDICI can provide €18 billion directly in the form of grants.

(2.2) Team Europe

The EU’s aid programme, and by the same token the Global Gateway, is made up of myriad actors.

Accompanying the community cooperation run by the European Commission there is the funding support offered by the EIB, in addition to that of the EBRD. In addition to such efforts there is also the development aid offered by each individual member state, many of which have their own aid agencies and even institutions for funding development and national development banks, as well as private sector resources and other actors such as civil society organisations (including non-governmental organisations).

This plurality of actors contributing to European aid, in the context of the European response to COVID-19 in the world, goes some way to explaining the urgency of recognising the need to join European forces to maximise its impact and visibility. Thus the Team Europe approach was born; this constitutes a new way of working, whereby all manner of European actors coordinate their external action more closely in order to present themselves to the world as part of the same Union.

The Team Europe approach thus becomes the second pillar in the execution of the Global Gateway: the pillar that determines the working methods, harnessing greater and closer coordination. This is the reason that all the projects encompassed within Global Gateway will be implemented through the Team Europe approach, which is made manifest in what are known as Team Europe Initiatives.

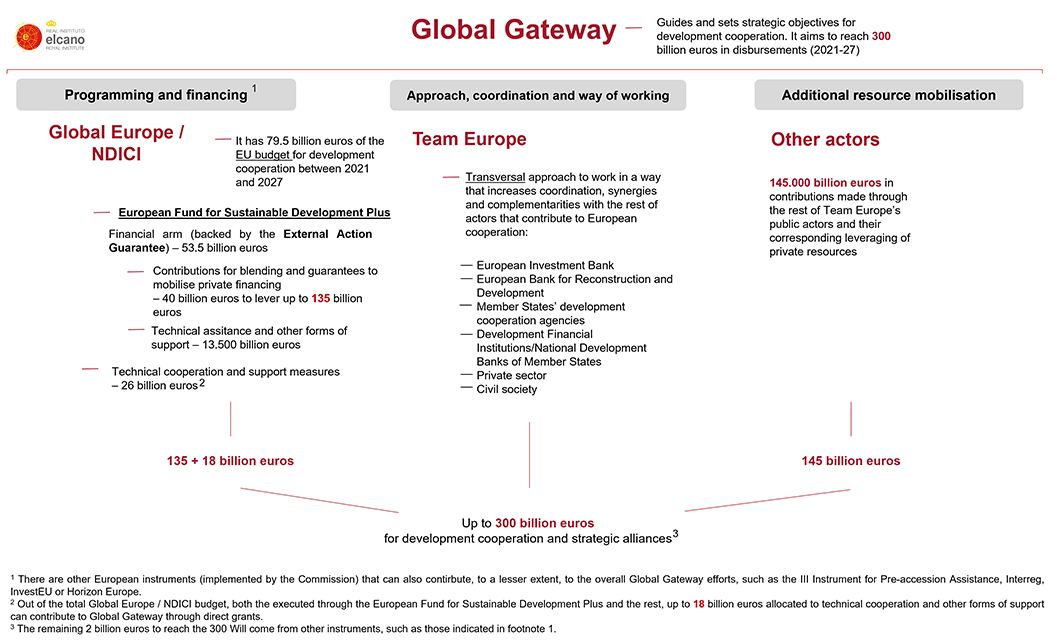

Figure 2. Global Gateway structure

(2) Of the total Global Europe/NDICI budget, both that executed through the European Fund for Sustainable Development Plus and the rest, up to €18 billion allocated to technical cooperation and other forms of support can contribute to Global Gateway through direct grants.

(3) The remaining €2 billion to reach the €300 billion figure will come from other instruments, such as those indicated in footnote 1.

Source: the authors.

(3) What is the distinctive value of the Global Gateway?

This strategy has often been likened to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), since it is also an initiative focused on investment in infrastructure, and because the advent of the Global Gateway comes at a time when China’s presence in the world continues to grow, particularly in countries that are, or could be, strategic partners for the EU in the new global geopolitical configuration.

However, this narrative of reaction and/or rivalry with China places significant limits on the differential potential and value of the Global Gateway.

The first factor that suggests the scant comparability between the two initiatives is that, while the amount of annual funding the Belt and Road Initiative deploys has stabilised in recent years at around US$70 billion (€64.1 billion), in terms of payment commitments the BRI has a value of US$1 trillion (€916 billion), magnitudes that are far higher than those applicable to European aid.

However, the differential value of the Global Gateway does not consist in trying to replace the BRI, a goal that is attainable neither in terms of size or of what the EU aspires to.

European cooperation, including the Global Gateway, offers a different type of association compared with that offered by the BRI. It is a geopolitical strategy based on partnerships that underpin the rules-based, multilateral international order, and that at the same time contribute to building integrated projects of societies founded on such shared values as democracy and the rule of law, respect for human rights, transparency in government affairs, the protection of workers’ rights, gender equality and sustainability;[2] all these are hallmarks of European cooperation and indeed their absence has triggered criticisms of the BRI in the past, and partly underlies China’s reasoning in launching a Global Development Initiative that is more conceptually aligned with this type of cooperation. It is also a matter of prioritising the quality of the projects and their social and environmental sustainability, and of constructing spaces for political dialogue with the partner countries, with the goal of promoting shared interests and combining forces for the preservation of global public goods.

The EU thus reveals itself as a dependable partner with which to enter into dialogue on the basis of a series of fundamental values. This European ambition to contribute to its partners’ integrated and sustainable development also manifests itself in the fact that its aid is predominantly channelled through grants, blended financing and guarantees, rather than loans, to avoid contributing to the problems of excessive levels of foreign debt that beset many emerging and developing nations.

(4) What the Global Gateway entails for cooperation with Latin America and the Caribbean

These characteristics of the Global Gateway –the values upon which it rests, the sectors that it focuses on and its major commitment to mobilising private investment– all point to Latin America and the Caribbean as a particularly appropriate region for such partnerships.

It is a region with which the EU shares fundamental values and enjoys a generally receptive climate towards investment, macroeconomic and financial stability, and more consolidated institutional and judicial frameworks than other emerging regions. Added to this are the host of sectoral interests and priorities shared by the two regions, such as international trade, the energy transition, the fight against climate change, digitalisation, the reduction of inequalities, the fight against cross-border organised crime and the defence of global public goods.

Although the budget allocated to this region in the Global Europe/NDICI is just €3.4 billion (5.6% of the budget allocation for geographic programmes), the EU has proposed deploying up to €45 billion in the region through the Global Gateway, by means of an investment agenda devoted to the region.

European cooperation has traditionally paid only oblique attention to the Latin American and Caribbean region, made up as it is of multiple medium-income countries with less urgent development needs. Recent geopolitical tensions, however, notably the Russian invasion of Ukraine, have laid bare the need for the EU to diversify its alliances and strengthen its links with like-minded partners. This accounts in part for the recent perception of greater European interest in strengthening relations with Latin America and the Caribbean, which are viewed as valuable partners in the multilateral system, and with which fundamental values and goals are shared.

This is made evident by the joint communication issued by the European Commission and the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy in June 2023, and the final declaration released at the EU-CELAC Summit held in July, as the first milestone of the Spanish Presidency of the Council of the EU. These documents reaffirm both regions’ commitment to enhancing their cooperation in key areas, and identify the Global Gateway as a central tool for achieving this end. Indeed, major specific agreements within the framework of the Global Gateway were signed with Chile, Argentina and Uruguay during the EU-CELAC Summit, and the same has now occurred with Mexico and Costa Rica, with which agreements have more recently been sealed during the Global Gateway Forum.[3]

Be that as it may, a deliberate policy decision has been taken by the EU to pay greater attention to Latin America and the Caribbean; it is a decision supported by the current global context and for which the launch of the Global Gateway may represent an opportunity that is not to be squandered.

(5) What are the next steps?

The Global Gateway thus has the potential to maximise the impact of European cooperation, both in terms of the social and economic development of its partners and in geopolitical terms, and this also undoubtedly applies to Latin America and the Caribbean as a privileged partner. It can help to raise the profile and multiply European resources (both financial and otherwise) for promoting global development. This has not gone unnoticed among partners of all sorts –whether the governments of other countries or European actors, particularly within the private sector, which feels greater attraction to this than previous cooperation initiatives– who have expressed their interest in becoming involved with the strategy.

In order for this to come to fruition, certain aspects remain to be defined or clarified, explained in part by the recentness of the initiative itself. The fact is that the classification of projects as Global Gateway projects up until now has been somewhat ad hoc, as the outcome of decisions taken at a high political level. As yet there are no well-defined or clear institutional procedures for proposing, formulating and implementing projects that will eventually form part of the Global Gateway. This lack of formalisation regarding how the strategy is to be implemented leads in turn to confusion surrounding specific mechanisms for deploying resources, the prioritisation and participation criteria and the added value of the strategy as part of the complex European cooperation architecture.

In this regard, progress is being made in the way the governance of the Global Gateway is defined, which should in principle gradually dispel some of the uncertainties mentiones above. Recently the Business Advisory Group was at last set up; this is a body that together with the Global Gateway Board is essential for creating a link between the initiative’s strategic orientation and its implementation in practice. Immediately prior to the Forum, the Global Gateway also approved a platform devoted to dialogue with civil societies and local authorities within the framework of the strategy.

There are still elements to be settled, such as the possible creation of a window especially devoted to the submission and approval of Global Gateway projects within the EFSD+ framework. Whatever happens, the way these processes evolve over the next few months and the manner and the extent to which the remaining uncertainties are resolved will have a major impact on the success and scope of the strategy, both generally and particularly in terms of Latin America and the Caribbean.

Conclusions

The Global Gateway initiative is taking shape, and with it the interest and will to participate between all manner of actors, public and private, both within the EU and among potential partners. This applies generally, and especially in the framework of the EU’s relations with the region of Latin America and the Caribbean.

The Global Gateway, which aspires to mobilising some €300 billion over the course of 2021-27, a figure markedly lower than that promised by China’s BRI, offers the prospect of a different type of partnership. This is a geopolitical strategy based on associations that underpin the international order founded upon rules and multilateralism, and that at the same time help to construct projects of integrated societies based on such shared values as democracy and the rule of law, respect for human rights, the transparency of government action, protection of workers’ rights, gender equality and sustainability; all of them hallmarks of European cooperation.

The EU thus seeks to position itself as a reliable partner open to engaging in dialogue on the basis of a series of fundamental values. This European ambition to contribute to the comprehensive and sustainable development of its partners also manifests itself in the fact that its aid is predominantly channelled through grants, blended financing and guarantees, rather than loans, to avoid contributing to the problems of excessive foreign debt burdens borne by many emerging and developing countries.

The initiative harbours significant potential, both in terms of the Union’s geopolitical presence and visibility, and in terms of its possible impact on development thanks to its focus on connectivity, digitalisation, the green transition, social inclusion and cohesion, healthcare and education.

The worldwide geopolitical context, the political capital invested in the Global Gateway and the imperative need to mobilise funding for development all align with this ambition. Latin America and the Caribbean will occupy the status of a privileged partner for this initiative.

[1] It is also envisaged that other European financial instruments such as the Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance III, Interreg, InvestEU and Horizon Europe will contribute to the Global Gateway, although in a more peripheral way.

[2] Understanding sustainability in its broadest sense, both in terms of the physical sustainability of structures and projects owing to their quality, and of course their sustainability in environmental terms.

[3] It is worth noting that Latin American and Caribbean participation in the Forum was limited compared with other regions (notably Africa), which suggests that work may still need to be done to ensure that the convocation is sufficiently broad and encompasses all EU partners in a similar way.