Original version in Spanish: La igualdad de género en la América de Trump.

Theme

What has been the impact of Donald Trump’s decisions and public policies on the rights and liberties of women during the first year of his Presidency?

Summary

During his first year, President Trump overturned a number of measures approved by his predecessor for fighting against gender inequality, a significant problem in the US. His government has suspended numerous measures against labour and salary discrimination, sexual harassment in the workplace and sexual abuse in schools and universities, along with other policies guaranteeing sexual and reproductive rights to women (including US government support for the UN Population Fund). The intense social and political mobilisation of women (in particular) that has responded to this rollback of protections could translate, via the midterm elections in November, into a much stronger presence of women in the institutions of a country currently falling far short of gender equality in politics and whose society appears intensely divided on this issue.

Analysis

The gender gap, even larger in 2017

Although no country in the world has yet managed to completely close the gender gap, the US does not belong to the small group of countries that have come the closest to achieving this goal. The Davos World Economic Forum’s 2017 Global Report on the Gender Gap,1 ranks the US as 49th of 144 countries included in the study (Spain occupies position number 24). Although this 2017 position is like that of the 2016 report (which ranked the US 45th of 144 countries),2 dit is a significant retreat compared with the 2015 edition of the report, in which the US was ranked 28th out of the 145 countries analysed.3In only two years the US has dropped 21 positions in the ranking.

Figure 1. Global gender gap ranking, 2017-15

| 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| US | 49 | 45 | 28 |

| Spain | 24 | 29 | 25 |

Source: the author based on data from the Global Gender Gap Report 2015, 2016 y 2017.

The results of the ‘political empowerment’ sub-index were even worse: the U.S. dropped to number 96 in this ranking (Spain is 22nd), falling 20 places from the previous year. The scant presence of women in this regard is a common feature of both the legislative (the House of Representatives and Senate) and executive (Federal and state) branches.

Figure 2. Global gender gap report: US ‘political empowerment’ sub-index ranking, 2017-15

| 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Political empowerment | 96 | 73 | 72 |

Source: the author based on data from the Global Gender Gap Report 2015, 2016 y 2017.

Although the US has closed the gender gap in education (as have 26 other countries, including Canada, France, Israel, the Netherlands, Brazil, Ireland, Australia, Belgium, Cuba and Finland, among others) and now ranks 19th in the economic opportunities sub-index (which measures the percentage of women in the working population, salary equality and professional position), the poor ranking in political empowerment suggests that despite achieving the equality of men and women in education, persistent barriers continue to block women from political power.

With respect to the legislative power, there has barely been any progress at all in recent years. The presence of women in the US Congress is far from gender parity. There are only 104 congresswomen –20 Senators (or 20% of the total) and 84 Representatives (19%)– and the number has not changed since 2015. Progress has been relatively limited, rising from 3% in 1971 to only 19% today.

Women are even less present in the executive branches of the 50 state governments: only four governors are women, a mere 8% at this level of political responsibility.

The gap is also notable in President Trump’s cabinet and administration: there are only three female Secretaries (of the Interior, Transportation and Education) compared with 13 men (occupying posts like Defence, State, Treasury and Justice).

According to the most recent data available,4of the 410 positions requiring Senate approval for which Trump has made nominations, only 21% are women (while 79% have been men). Although Obama did not achieve parity in the appointments of Administration officials, he appointed women to 43% of the positions (and men to 57%). It is worth remembering in this regard that the US labour force, according to World Bank data, is 46% female and 54% male.

Given that the gender gap in political participation is already significant, any deterioration in female presence has a major impact. Furthermore, the gap in this realm requires proactive measures, sustained over time, to achieve and consolidate the presence of women in positions of political responsibility.

Dismantling the Obama agenda: the rollback of women’s rights and liberties

Key issues –like wage and salary equality, paid maternity leave (only 25% of women enjoy this right in the US, the only developed country that does not guarantee it), sexual health and reproductive rights, and gender violence– remain unresolved in the US.5

President Trump has proceeded, step by step, to dismantle the progress made by his predecessor on women’s rights and liberties, not only with respect to sexual and reproductive health (which directly conflicts with the ultraconservative ideology of his agenda) but also in the areas of labour discrimination and workplace sexual harassment, and in education (especially the universities) –objectives which should not conflict with any religious or moral beliefs (particularly sexual and reproductive rights)–. The decisions taken by the current Administration during 2017 have been in line with the treatment of women’s rights characteristic of Trump’s election campaign, during which he ostentatiously displayed his disdain for women with his sexist and chauvinist statements on many occasions.

Consistent with all of this, one of the first executive orders6the President signed was the prohibition of federal funds to organisations that advise other countries on voluntary pregnancy termination, applying the so-called ‘Global Gag Rule’ which stipulates that any NGO that receives federal funds should not promote abortion internationally, or provide any related services.

Applied by each Republican Administration since President Reagan first adopted it in 1984, and reversed by the Democratic Administrations of Presidents Clinton (in 1993 and 2003) and Obama (from January 2009 until January 2017), this rule imposes a financial block on any organisation that supports voluntary pregnancy termination in any part of the world.7Planned Parenthood, one of the most well-known organisations –with family planning and prenatal care programmes in many countries (in addition to providing such health services to more than two and half million patients in the US)– has been one of the NGOs most affected by the re-instatement of this rule.

In this same vein, alleging that activities of the UN Population Agency violated US abortion policy, in April President Trump suspended government funding8to this agency (which provides family planning and reproductive health services in more than 150 countries). As the UN agency pointed out, in 2017 the Population Fund contributed to saving the lives of thousands of women during childbirth and early child-rearing, and to preventing nearly a million pregnancies and 300,000 unsafe abortions. Due to the loss of the US contribution, the spokesperson for the Secretary General of the United Nations (who has claimed that the US decision could have devastating effects on the most vulnerable women and children and their families around the world) has appealed to other donors to increase their contributions.

In addition, the decision to eliminate the obligation of employers to include coverage for birth control in their employee health care insurance (guaranteed by Obamacare) has limited access to contraceptives for hundreds of thousands of women. The decision allows any company (as well as any university), justifying itself on ‘sincere religious beliefs or moral conviction’ to decline to provide coverage for contraceptives, a privileged exception previously only granted to churches and houses of worship.

Last August, the government eliminated one of the Obama Administration’s labour initiatives designed to fight against gender and minority discrimination in the labour market and workplace. The rule was finalised in September 2016 –after six years of research9on workplace discrimination, and consultations with business people, payroll management companies, academics and focus groups– and would have come into effect in March 2017. The rule would have obliged companies to detail their employee salaries in terms of ethnic group, race and gender, and to report the information to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The objective was to discover where the largest gaps were produced, and to help correct them. By eliminating this measure (considered by the current Administration as a regulatory drag on companies and of doubtful usefulness), the public administrations will continue to be deprived of the data that would identify the sources of gender inequality and, therefore, of the possibility of fighting against it.

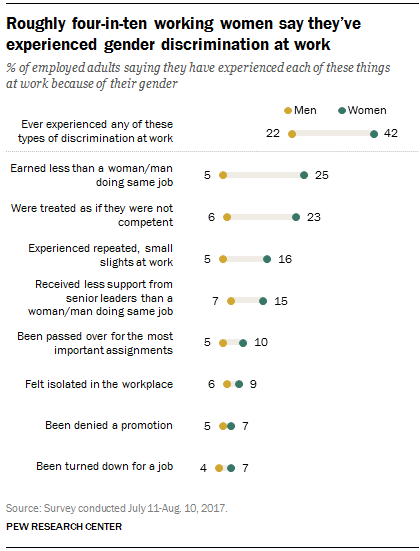

According to a recent survey, 42% of women claim to have experienced gender discrimination in the workplace.

Furthermore, the Fair Pay and Safe Workplaces rules,10–adopted by the Obama Administration to forbid companies with federal contracts from keeping secret incidents of sexual harassment and workplace discrimination– was also overturned. This 2014 executive order stopped companies with federal contracts –which collectively employ 26 million people– from forcing their employees to resolve harassment cases by means of arbitration (a typical practice to prevent cases and details from becoming public). The rules put in place by Obama’s executive order protected women in two ways: (1) it made their salaries transparent; and (2) it expressly prohibited employers from forcing arbitration on sexual harassment cases. It is worth remembering that a woman earns, on average, 83 cents per dollar earned by a man.

Other measures of the previous Administration to protect victims of sexual harassment and abuse in schools and universities were also rescinded. The document in question, approved in 2011, defined sexual abuse and established a new paradigm for school policy on sexual abuse cases. With these measures in place, any evidence was sufficient to begin an investigation. The new norm approved by the Trump Administration toughens the conditions for launching an investigation (requiring ‘clear and convincing evidence’),11Women’s rights organisations claim that this will produce a ‘chilling effect’ upon the reporting of sexual aggression and make campuses less safe. The problem of campus violence is not insignificant.12

One in five women and one in every 16 men are sexually assaulted on university campuses. More than 90% do not press charges.

However, it is also true that the ‘checks and balances’ of the US model have played a key role in protecting women’s rights. Some states, like California, Delaware, Maryland, New York and Virginia, have launched legal suits against the federal decision to suppress access to contraceptives; other states, like Hawaii, Maine and Nevada, have guaranteed access to birth-control methods for a year. Nevertheless, the impact of these federal decisions will be difficult to reverse, and they will certainly have a significant impact on the life of women, especially the most vulnerable with the fewest resources.

Finally, it should be noted that the first federal budget presented by President Trump13 did not contain –literally, at all, and for the first time in many years– a single reference to women. This is in stark contrast with the budgets from previous fiscal years. To cite just the most recent examples, the last three Obama budgets included significant mention of and support for women’s rights:

- The FY2017 budget recognised the contribution of women to the labour force and the promotion of women’s rights in the world.

- The FY2016 budget included investment in health, education and security for girls and teenagers, migrant women, the Nutrition Programme for women and children, and support measures for pregnant women.

- The FY2015 budget included support for the promotion of women in the STEM fields –science, technology and mathematics– and an important package of investments and other efforts in the fight against gender violence..

One final point: many positions created by the previous Administration to promote women’s rights remain vacant, including the Ambassador at Large for Global Women’s Issues in the Department of State14and the Director of the Office on Violence against Women in the Department of Justice. The White House Council on Women and Girls –an institution created by President Obama with the object of assuring coordination between all the agencies and units of the Administration on issues affecting women and girls– also remains inactive.

Women: leading role in the November 2018 midterm elections?

The election of President Trump has generated greater interest in politics –especially among Democrats, and particularly among women–. Indeed, the Trump victory has served a catalyst for the social mobilisation of women and feminist organisations.

The largest recent demonstrations in the US took place on 20 January 2017 in many cities across the country (as well as in many other countries) to protest President Trump’s gender policies, reminding people that women’s rights ‘are human rights’. More demonstrations were convoked in many US cities on 20 and 21 January 2018 (and again in other countries), this time carrying the motto ‘power to the polls’. Therefore, the Trump Presidency could have a direct effect on the political participation of women, one of the areas, as mentioned above, where the gender gap is the widest.

The midterm elections coming up in November 2018 –which will elect 33 senators, all 435 members of the House of Representatives and 19 state governors– could bring to the fore this effect and result in greater female political participation. The fielding of female candidates by the Democratic Party is beginning to reach unprecedented proportions. Organisations like EMILY’s list,15a political action committee (PAC) dedicated to supporting female Democratic candidates, and other similar formations are playing an active role in providing training and consulting to women candidates at the state and local levels. Since the election of President Trump, more than 26,000 women have contacted EMILY’s list to ask for support for their possible candidacies.

According to the most recent data from the Center for American Women and Politics of the Eagleton Institute for Politics at the Rutgers University,16 the number of female candidates for the House of Representatives has grown exponentially to 397 candidates (217 Democrats and 80 Republicans), in contrast with the actual number of 84 current female officeholders (62 Democrats and 22 Republicans).

There will also be gubernatorial elections in 33 states in which there are projections for more women candidates. According to the most recent data17 upwards of 79 women (48 Democrats and 31 Republicans) will run for state-level executive office in a wide range of states.

It will not be possible to undertake a deeper evaluation of the importance of this political mobilisation –and to know just how significant a percentage of women will ultimately be running in the 6 November elections– until the results of the upcoming primary elections (which begin in a few weeks) can be factored in. But without any doubt the number of female pre-candidates has already reach a historic high which could, if translated into definitive candidates and into votes on 6 November, contribute to an historic expansion of the presence of women at the federal legislative and state executive levels of government.

Perceptions of gender equality in the US

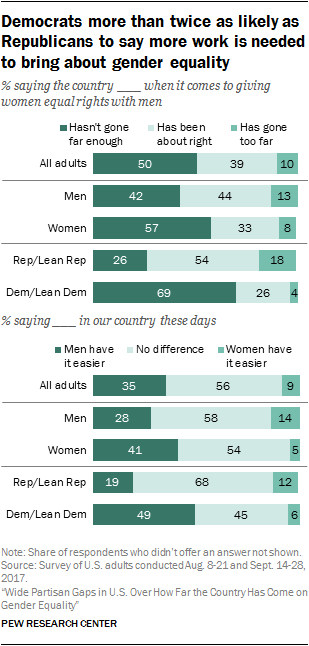

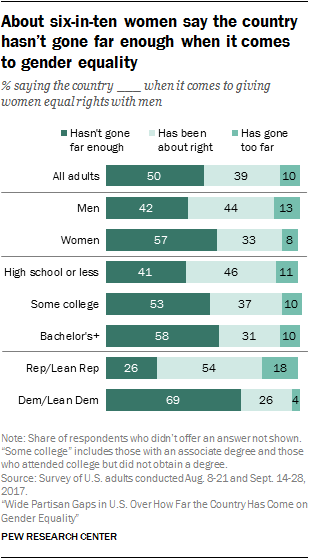

Public opinion on matters of gender equality reflect a deep division in the country, according to recent studies by the Pew Research Center. This division is explained by, among other reasons, ‘the partisan rupture that impregnates American values and culture in these times’. The deep polarisation of US society, made plain by the last presidential election, is also reflected in the public’s perception of the current gender equality situation and of the need (or lack of it) to use public policy to advance gender equality.

Although the majority of Americans agree that women should have the same rights as men (82%), only half believe that the country needs to advance further, and 39% believe ‘things should stay as they are’.

In addition, the division between Democrats and Republicans is notable. While Democrats are very unsatisfied with the country’s progress on this issue (69% believe the country has not progressed enough to guarantee equal rights for women), only 26% of Republicans consider that there is more to do, and 54% believe the situation is good as it is.

The differences between men and women are also important. While 57% of women believe the country has not progressed enough (versus 33% who believe it has), only 42% of men do not believe the country has made enough progress on gender equality, and as many as 44% feel this situation is good as it is. If we combine the gender and political positioning variables, then 74% of female Democrats and 64% of male Democrats believe the country still has work to do to achieve gender equality. On the other hand, the percentage of female Republicans that feel that not enough has been done only comes to 33% (along with only 20% of Republican men). Furthermore, 22% of Republican men and 14% of Republican women believe the country has gone ‘too far’.

US public opinion of the progress of women’s rights and gender equality reflects a clear polarisation in the country, but it also points to the difficulties inherent in overcoming stereotypes. This is clear from the fact that 44% of men describe the situation as good and 22% of Republican men and 14% of Republican woman believe that the country ‘has gone too far’ with regard to gender equality.

Conclusions

There is no doubt that President Trump is treating gender equality and related issues with a deeply conservative (and anti-feminist) ideological slant, without accounting for the consequences that this inequality between men and women has for social and economic stability. His openly sexist and chauvinist electoral campaign presaged restrictions on rights and liberties already gained by women, and he has already begun to implement such an agenda during the first year of this term.

All of the initiatives underway will have an impact, to a larger or lesser degree, on the lives of women and their families, especially the most underprivileged. The lack of female role models in positions of political responsibility, the culture of silence surrounding cases of gender violence, the salary gap and the lack of free access to family planning, all imply barriers to real and effective equality –in addition to perpetuating the gender stereotypes which impede the cultural change still pending in most countries– as well as significant related economic losses.

Nevertheless, gender inequality in the US cannot be attributed to the current President or Administration. For a long-consolidated democracy like the US, and as the leading economic power of the world, the county has long had a very wide gap and only in recent years were some concrete measures adopted to combat gender inequality.

The ultimate impact on women’s rights of the Trump Presidency is still difficult to assess, but it is likely that the tendency recently begun will continue, and possibly broaden in scope. In any case, given that closing the gap requires permanent, sustained measures, the new policies will contribute to further widening the inequalities, making the achievement of real gender equality more difficult and distant.

Another effect of President Trump’s first year –unforeseeable and certainly unwelcomed by the current Administration– has been the mobilisation of women and feminist organisations through many large demonstrations over the past year. These unprecedented political demonstrations, along with the hundreds of female candidates slated to run in the upcoming mid-term elections, represent a firm rejection of the presumed ‘new normality’ of an openly chauvinist and sexist president. Should the primaries confirm these women candidates –and then convert themselves into electoral victories– a change in the balance of power between the parties could occur, along with a significant increase in the presence of women in the Senate, the House of Representatives and in State-level executive offices.

Finally, one should not underestimate the global impact of President Trump’s position on gender equality, not only in terms of budget appropriations to UN organisations working in favour of gender equality but also in terms of influence over other countries. The commitment of the US to Goal Number Five of the Sustainable Development Goals –gender equality and empowerment of all women and girls by 2030– is now seriously in doubt.

María Solanas Cardín

Project Manager, Elcano Royal Institute | @Maria_SolanasC

1 2017 Global Gender Gap Report.

2 2016 Global Gender Gap Report.

3 2015 Global Gender Gap Report.

5 María Solanas (2016), “Género y Elecciones Presidenciales en EEUU 2016”, ARI nº 67/2016, Real Instituto Elcano.

6 See the Presidential revocation of the “Mexico City Policy”.

7 Center for Health and gender equity on Global gag rule.

8 See the statement of the UN Population Fund after the suspension of U.S. funding.

9 Final Experts Report on the collection of salary data, 2015.

10 Executive Order on Fair pay and safe workplaces, 2014.

11 New Interim Guidelines on Campus Sexual Misconduct.

12 National Sexual Violence Research Center.

14 See: Global Women’s Issues (Ambassador at large): Vacant.

15 EMILY’s list.

16 Center for American Women and Politics, Universidad Rutgers.

17 Center for American Women and Politics, Universidad Rutgers.