Summary

This article[1] summarises the transformations that Spain has undergone since it joined the European Community and presents the main challenges facing the country, both at home and abroad. A set of especially significant indicators have been chosen for this discussion of Spain’s transformation and its rapid process of economic modernisation and Europeanisation.

1. Introduction

The Treaty of Accession admitting Spain to the European Community was signed on 12 June 1985 in the Throne Room of the RoyalPalace in Madrid, and took effect on 1 January 1986. After long years of negotiations and certain hesitation and fear, Spain began a process of profound political, economic and social transformation in the framework of European integration. The aim of this article is to summarise the transformations that Spain has undergone since it joined the European Community and to present the main challenges facing the country, both at home and abroad. A set of especially significant indicators have been chosen for this discussion of Spain’s transformation and its rapid process of economic modernisation and Europeanisation.

On the economic front, the figures leave no room for doubt: in 20 years Spain has gone from being a country whose per capita income was 71% of the European average to now practically reaching the average of the expanded 25-member Union; it has progressed from being a recipient of European funds to being almost a net contributor and from being a country that received foreign direct investment to one with an important international presence and large multinational companies. In a short period of time, Spain has also gone from traditionally being a country of emigrants to having around 3.5 million resident foreigners. As a result, after having brought its inflation, employment and debt rates in line with those of its European partners and having restructured its public accounts, Spain is now the world’s eighth-largest economy, as well as being one the most open and dynamic ones in Europe, and is an exemplary member of the Eurozone.

At the political level, the Spanish show a very strong feeling of identification with and support for the European integration process (stronger than in other countries). It is also revealing to see to what extent the Spanish have developed new political attitudes and values that demonstrate a well-rooted democratic political culture, great satisfaction with the decentralisation process and growing international solidarity. All this both reveals and underpins a process by which Spain, traditionally absent from the international scene, has worked hard to put itself among the countries most committed to development, peace and international security. The strength of the country’s culture and language, in addition to values that reflect the active commitment of the Spanish to a more open, more equitable and more democratic world, have given rise to a scenario radically different than that seen in the introverted and isolated Spain of the past.

However, Spain also faces significant challenges. First of all, the transformation of its productive structure is still not complete and further effort is needed for its companies to be able to compete forcefully in the context of the newly expanded Union and the global economy. Low productivity and a lacklustre export sector are two issues that must be addressed. To do this, it will be necessary to continue structural reforms and the liberalisation of the goods markets and production factors, as well as investing more in R+D to strengthen the technological intensity of the goods and services produced and exported. If there is no clear determination to innovate, it will be very difficult to make this jump.

Finally, on the international scene, with the enlargement of the European Union to 27 members and with the existence of huge challenges in terms of peace and security, sustainability and access to and distribution of resources, Spain has yet to fully take its place among the largest and most influential nations, and to build capacities and institutions that both support and enable its role as a leader. As a result, despite its best intentions, unless Spain acquires the necessary material resources, it will not be able to make a substantial contribution to global governance.

2. Economic Transformation

The Dimensions of Change

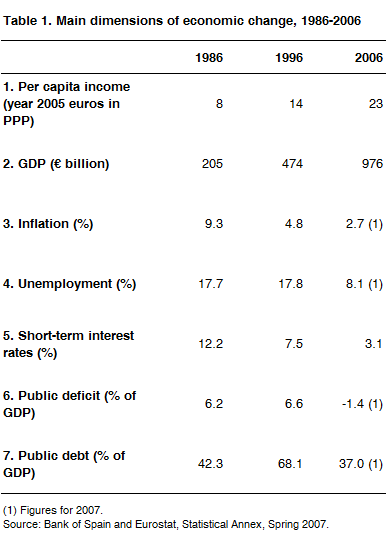

The Spanish economy has undergone a spectacular transformation in recent decades. Although economic acceleration began to be felt in 1959, with the Stabilisation Plan that put an end to the model of self-sufficiency, entry into the European Union provided a further boost to the country’s opening and convergence with developed countries. Table 1 shows the main dimensions of economic change in Spain in the past twenty years.

Most striking is the growth of per capita income, which measured in purchasing power parity (PPP) in year 2005 euros, has nearly trebled from €8,000 euros in 1985 to over €23,000 in 2005. Also during its 20 years in the EU, the Spanish economy has accumulated a total of 17% more GDP growth than the European average.This has meant that the weight of the Spanish economy in the EU-15 has increased from 8% in 1986 to nearly 10% 20 years later. Indeed, the Spanish economy, with a GDP of over €1 trillion in 2007, has consolidated its position as the eighth-largest economy in the world and one of the most dynamic in Europe.

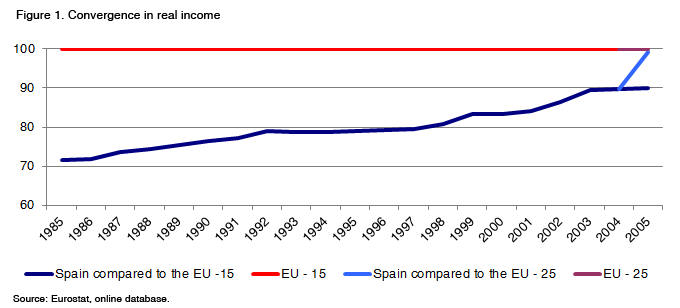

As a result of this growth in per capita terms, there has been rapid real convergence with the EU average (see Figure 1). Per capita income rose from 71% of the EU-15 average in 1985 to over 90% in 2005, narrowing the income gap with Europe by nearly 20% in 20 years. The periods of greatest convergence were 1985-90 (the first years in the EU) and 1997-2006 (coinciding with the inclusion of Spain in the Economic and Monetary Union). When 10 new members joined the EU in 2004 –all of them with income levels lower than Spain’s– this gave a new boost to Spain’s convergence with the EU, putting the country’s per capita GDP above 99% of the EU-25 average (what is known as the ‘statistical effect’ of the enlargement).

There has also been a very significant fall in the unemployment rate, especially since 1994. In 1985, Spain had an unemployment rate of around 18% –nearly double the European average–. Twenty years later, it has dropped to 8%, which is nearly the same level as in the EU-15. However, there has not been a linear reduction in unemployment. After falling to 13% in 1990-91, it reached its peak (20%) in 1994, then dropped nearly 10 percentage points in 10 years. In fact, since 1997 jobs have been created in Spain at an average rate of 3.6% a year, treble the EU-15 average. Also, even though the female unemployment rate (over 11%) continues to be five percentage points higher than the rate for men, Spain is not far from full employment for men. Finally, it is important to note that the creation of employment has been so significant that it has made it possible to absorb a growing inflow of people that has made Spain the EU country that has received the most immigrants since 2002. In short, thanks to its dynamic economy and the (still incomplete) reforms of the labour market, Spain is no longer the EU country with the highest unemployment rate and the lowest level of activity.

Although inflation in 2007 remained about 1% higher than in the Eurozone as a whole, the country has made significant efforts to close this gap, which in 1986 was nearly 6%. Except for a rise between 1989 and 1992, inflation has been falling continuously, enabling Spain to reach the convergence of prices necessary to join the euro in 1999. This successful control of prices is attributable to the credibility of the Bank of Spain (independent since 1994) and, since the creation of the euro, to the credibility of the European Central Bank. Slower growth of wages, lower capital costs (lower interest rates, which have dropped from 12% in 1986 to 3% in 2006), and a sharp reduction in the public debt and deficit, have facilitated the control of prices (see Table 1). Still, the existence of a permanent inflation gap between Spain and the EU-15, as well as the difficulties encountered when trying to reduce it, pose a constant risk of diminished competitiveness, an issue we will deal with later.

The Foreign Sector (Investment, Trade and European Funds)

One of the most outstanding factors in the changes in the Spanish economy in the past 20 years has been the foreign sector. The globalisation process has been significant and the Spanish economy is now one of the most open in the European Union. This phenomenon can be seen both in terms of trade and foreign investment.

In terms of trade, the Spanish economy has undergone a spectacular opening-up process. In the past four decades, the weight of the export and import of goods and services as a percentage of GDP has increased more than six fold. The engine driving this process has been Spain’s integration in the European Union, in its different phases and forms. First of all, trade flows were boosted by the economic opening that followed the Stabilisation Plan in 1959 and by the signing of the Common Market agreement in 1970. Then, in 1986, when Spain joined the Community, these flows rose yet again, reaching their peak in 2000. In 2006, Spain’s economic openness (imports plus exports as a percentage of GDP) stood at around 70%.

As for foreign direct investment, there has been a striking process of internationalisation in which Spanish multinational companies have gone from investing €2 billion in 1990 to over €40 billion in 2006. Until 1996, foreign direct investment in Spain was greater than Spanish investment abroad. It was in 1997, the first year when Spanish foreign investment abroad was greater than foreign direct investment in Spain, that the internationalisation of Spanish companies began to accelerate. After the privatisation of big public companies, Spanish companies made enormous foreign investments that peaked in 2000, with €59.34 billion in foreign direct investment (nearly 10% of GDP). Most of this investment was focused on Latin America and, to a lesser extent, on the EU.

Finally, the key role of European funds cannot be ignored. Since it joined the EU, Spain has contributed €117 billion and has received €211 billion, for a positive balance of €93.35 billion in 2004 prices. These funds have represented an average of 0.8% of Spain’s annual GDP over the past several years, or around €5,275 per inhabitant over the period (around €260 per person per year). This flow has made it possible to finance a large number of infrastructure, social cohesion and regional projects. In the period 1986-2000 there was a significant reduction in the gap between the per capita income in the various autonomous regions and the Spanish national average, suggesting a reduction in regional inequalities.

Challenges

Despite these successes, economic transformation is far from complete. Important work remains to be done, particularly in terms of increasing the productivity growth rate, producing goods and services that are more knowledge-intensive and reducing the current account deficit, which means reducing the inflation differential with the EU, increasing the domestic savings rate, reforming the labour market, improving the competitiveness of exports and restructuring the energy model.

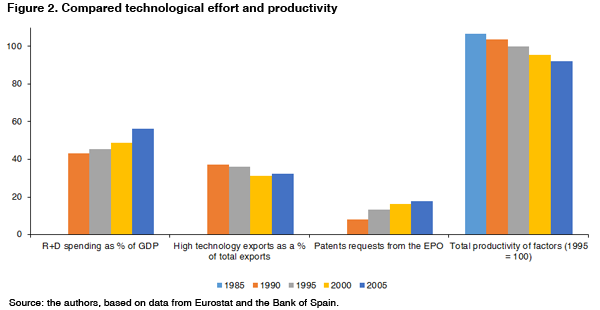

As shown in Figure 2, Spain is still significantly behind the EU-15 average in terms of technology, which leads to slow productivity growth and a continual loss of competitiveness expressed in the form of a growing current account deficit (over 8.5% of GDP in 2007). Productivity per worker in Spain has increased at an average of 0.6% a year since 1996, half the EU-15 average. At the same time, the overall productivity of factors, which measures all those intangibles that are not included in the overall productivity of the use of labour and capital (organisational capacity and innovation, quality of capital, the education and experience of the labour force and the entrepreneurial capacity of the population) stood in 2006 at around 90% of the EU average and shows a worrying downward trend, given that in 1986 it was above the EU average.

However, the indicator that best reveals Spain’s relative technological lag is investment in research and development (R+D) as a percentage of GDP. This type of investment is essential to encourage innovation, to increase the added value of the goods and services produced, to generate increases in productivity and to increase the income and well-being of the population. In 1985, Spain invested only 0.57% of GDP in R+D, while the EU-15 invested 1.86%. Twenty years later, although spending has risen more quickly in Spain than in Europe, the difference continues to be considerable, since Spain invests 1.07% of GDP and the EU-15 invests 1.95%, or, as the figure shows, Spain stands at 60% of the EU-15 level. The research commitment of other advanced countries is even greater than the EU’s. For example, the US invests 2.6% of its GDP in R+D, South Korea 2.9% and Japan 3.1%. This situation means that Spain will have to make further efforts to put itself at least at the level of R+D found in the EU countries.

A reflection of the low investment in R+D is the relatively low number of patents issued in Spain and the relatively small volume of high-technology exports. Despite having doubled the number patents presented in the past 20 years to the European Patents Office, Spain remains below 20% of the EU-15 average, that is, for every 100 patents presented on average each year in each of the EU countries, only 18 are presented in Spain. Furthermore, Spain has not managed to increase the weight of its high-tech exports among total exports, nor has it diversified geographically (over 60% of Spanish foreign trade is with Germany, France, Italy, Portugal and the UK). As Figure 2 shows, only 6% of Spanish exports are high-tech (for an extremely low 32% of the EU-15 average). Exports of this kind are knowledge-, capital- and labour-intensive and, therefore, tend be in high demand abroad, as well as having relatively high prices. The root of the problem is that Spain has not been able to significantly increase its production of this kind of goods and therefore cannot export them.

In short, no one would disagree that in the past few decades (and the past 14 years in particular) the Spanish economy has been a success story with real convergence with the EU. However, in a medium-term adjustment is needed, that is, a deceleration of consumption and imports to release the Spanish economy from such great inflationary pressure and to regain competitiveness, export more, rebalance the foreign exchange balance and not depend so much on internal demand and the real estate boom. Since the arrival of the euro means that this adjustment cannot be accomplished through devaluation, it will have to be done through changes in relative prices, that is, through a slower growth in real wages than in other member countries for a considerable period of time. But in the long term, the only way to ensure sustainable growth is to increase innovation and strengthen structural reforms in order to raise the quality of our exports, so that Spain does not have to compete solely on the basis of cost (fortunately Spain is no longer a country with low wages).

Like the EU, Spain is also highly dependent on foreign energy, especially oil and gas, which make up nearly 70% of primary energy consumption. The challenge, therefore, is to reduce external dependence by diversifying energy sources (especially by increasing the share of renewable energies), improving the efficiency of consumption (which is still 20% below the EU-15 average) and helping to build a common European energy policy that will reduce the EU’s geo-strategic weaknesses over the long term.

3. The Socio-political Transformation

With its entry into the European Community, Spain ended its marginalisation vis-à-vis Europe and began an active policy of not only economic, but also socio-political Europeanisation, while increasing the country’s presence and profile in the world. The success of the integration process was culminated with the inclusion of Spain in the Economic and Monetary Union in 1998. Spain’s entry into the EC in 1986 was the culmination of the democratisation process initiated a decade earlier, after the death of General Franco in November 1975. No one today questions that fact that Spain’s participation in the European integration process has contributed decisively not only to its economic and social modernisation, but also to its internal political stability and its profile in Europe and around the world.

Changes in the Political System

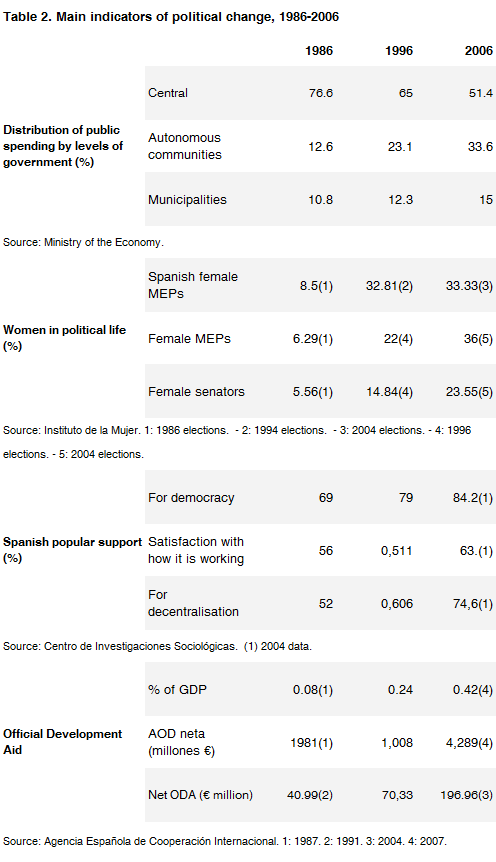

The economic and social transition of Spain since it joined the EU has been accompanied by an intense process of political decentralisation set in motion by the Constitution of 1978. Spain today is a highly decentralised country in which central government spending accounts for a very small proportion of overall public spending. Along with the central administration there are the autonomous community administrations, as well as local authorities, all of which have constitutionally recognised financial independence. Compared with 1979, when the central government managed 91% of public spending, in 2006 it managed only 20.7% of the total consolidated spending of public administrations, not including the 30.7% corresponding to the social security system. Meanwhile, the share of resources managed by the various decentralised administrations came to 48.6% (excluding interest on the public debt).

In addition to the decentralisation process, the modernisation of the SpanishState and government has encompassed other dimensions, as has also been the case in other developed countries. On one hand, in the past 20 years the State has strengthened its powers relating to citizen welfare, such as workplace security and the natural environment. At the same time, it has reduced its presence in sectors such as telecommunications, water and electricity. After an intense wave of privatisations, public sector business and industrial activity now accounts for less than 1% of GDP, compared with 6.8% in 1982. Spain’s entry into the EC also meant the start of the process of modernising its public administration system. The Spanish administration today provides its services more transparently and efficiently, and is more concerned about performance and about the end users of public services. Similar to what has happened in other EU countries, the process of improving public management continues today and, in the case of Spain, has given rise to initiatives such as the State Agencies Act (Ley de Agencias Estatales), the Code of Good Government (Código de Buen Gobierno), the Electronic Administration Act (Ley de Administración Electrónica) and the Basic Statute on Public Employment (Estatuto Básico del Empleado Público).

Convergence with Europe is also evident in the growing role of women in Spanish political life. According to the Interparliamentary Union (IPU), an average of 16.4% of the world’s national parliamentarians were women in 2006. Starting at a very low level (only 6.29% of parliamentarians were women in 1986), Spain has risen to seventh place in the world, ahead of countries such as France and Germany, with women accounting for 36% of congressional representatives today. The proportion of female MEPs among total Spanish representatives (33.33%) is also above the European average (27.87%). Also, in terms of the proportion of women in the armed forces (13.5%), Spain is ranked third in world after Canada and the US, and first in Europe.

Attitudes and Values

The modernisation of the State, economic development and the globalisation process have helped transform the values system of Spanish society. The values of peace, democracy and prosperity expressed in the Constitution of 1978 have translated into widespread support among Spanish citizens for the democratic process, the European integration process and the principle of solidarity.

Support for the democratic system and the decentralisation process, as well as satisfaction with the functioning of democracy in Spain, has grown continuously over the past 20 years. Over 84% of Spaniards prefer democracy to any other form of government, while 63.5% are satisfied with how it is working and 74.6% support the decentralisation process. At the same time, ‘post-materialist’ values, such as the promotion of political participation and the protection of freedom of expression have been gaining ground as top national priorities for the average Spanish citizen, compared to other types of values, such as the struggle to control inflation or the maintenance of public order. This trend has been accompanied by an increase in citizen solidarity over the past two decades, and has been supported by the modernisation of the State, the increase in economic prosperity and greater social welfare.

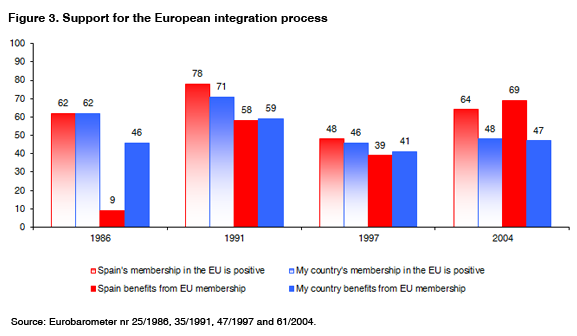

The obvious solidity of the political, economic, strategic and even emotional foundations on which Spain’s membership in Europe are based, make it clear that the European project is one that has been shared by the entire society and, for the same reason, its success cannot be attributed to any particular government, but rather to society as a whole. In Spain’s first years in the European Community, very few Spaniards (barely 9%) believed that membership would be beneficial to the country. Despite this, 62% of people (a value equivalent to the European average) believed that belonging to the European Community was a positive thing. The perception the EU membership brings benefits to Spain has increased since then. At present, 69% of Spaniards feel that Spain has benefited from its membership in the Union –a figure much higher than the European average (47%)–. The tendency to consider EU membership as something positive has consistently remained above the European average over the past 20 years, except during the crisis of 1993-94. Since Spain joined the third stage of the Economic and Monetary Union, this difference has become even greater. At present, 68% of Spaniards believe that EU membership is positive, versus the European average of 48%.

The high level of Spanish support for the European integration process has translated into a greater feeling of European identity and confidence in its institutions. In Spain, nearly 65% of the population say they feel European, versus 56% in the EU-15 and 58% in the EU-25, or compared with the sub-45% figures we find in other member countries such as Lithuania, Finland, the CzechRepublic, the UK, Greece and Hungary. The confidence in European institutions expressed by the Spanish is among the highest in the Union. The European institution that has most won the trust of the Spanish over the past two decades is the European Parliament. At present, 52%, 53% and 62% of Spaniards say that they trust the European Council, Commission and Parliament, respectively, versus the European averages of 40%, 47% and 54%. However, there has been give and take on the road to Europe. Spain has not only supported and benefited from the European project; it has also made positive contributions to its development. European citizenship, social cohesion and issues involving justice and the interior: Spain has made its mark in all these areas. Spain has also made significant contributions to developing the role of the regions, linguistic and cultural diversity within the Union, and relations with Latin America.

Spain’s Role in the World

The consolidation of democracy and modernisation of government and administration have been accompanied by a new image in the world. European integration has helped Spain’s efforts to open itself to the rest of the world and improve its role on the international scene. This trend is reflected in areas such as aid to developing countries, diplomatic and business initiatives, and the presence of Spanish armed forces on international missions.

The development of Spanish foreign and defence policy in the past two decades has been closely linked to the development of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and Spain’s integration into NATO. The Europeanisation of Spanish foreign policy has been very strong, not only in terms of its areas of traditional interest, but also in terms of the new areas of foreign policy where it has made international commitments. Spain has successfully promoted a European policy for Latin America and the Mediterranean, while adopting the international interests of other members of the Union in other regions of the world.

Since 1986, when Spain joined the European Union and confirmed its participation in NATO by referendum, over 59,000 members of the Spanish armed forces have participated in foreign missions under the flag of the UN, NATO or, more recently, the EU. In some cases, such as Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo, Spain has been continuously present for several years. Between 1989 and 2005, 618 Spanish army representatives acted as international observers on missions in nearly 20 countries. Spain’s entry into the Atlantic Alliance meant the start of an important process of modernisation of the Spanish armed forces, which was strengthened by the development of a common EU security and defence policy in the late 1990s. This process of adaptation has brought significant changes in organisation, doctrine, command and control systems, equipment and training procedures, which has enabled the Spanish armed forces today to be able to operate jointly with the armed forces of other countries under multinational command.

Spain’s growing international role is visible not only in its military deployment, but also in its diplomatic presence in the world. In the past two decades, the number of foreign embassies and consulates has grown significantly, as have the number of Spanish workers in international agencies and the presence of Spanish companies in other countries. At the same time, Spain’s net ODA (Official Development Assistance) has increased from under €200 million in 1987 to €4.289 billion in 2007. Thirty years ago Spain was a net recipient of ODA, but today it allocates 0.42% of GDP to development cooperation. This share of GDP puts it above the average of donor countries that are members of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC). This trend is reflected not only in increased prosperity in Spain, but also in the solidarity felt by the citizens of the country.

Spain’s new position on the international scene has been accompanied and facilitated by the strength of the Spanish language, a key factor in ‘soft power’. At present, about 350 million people around the world speak Spanish as their mother tongue (nearly 100 million more than 20 years ago), making it the fourth-largest linguistic community on the planet. Furthermore, around 10% of Internet users use Spanish as their main language. Only English and Chinese surpass Spanish on these two counts. This effort has been supported by the opening of over 60 Instituto Cervantes centres around the world since 1992. Interest in Spanish culture has made Spain the EU country that receives the most Erasmus students each year.

Despite the success of Spain’s socio-political transformation in the framework of its integration in the European project, major challenges remain in the area of foreign policy. Recent events in Latin America, on the one hand, and the Middle East conflict and the difficulties of bringing the Barcelona Process to fruition, on the other, mean that it will be necessary to work to consolidate European policy in these regions, by supporting the regional integration process in Latin America and the new Mediterranean neighbourhood policy. Spain will also have to strengthen its relations with the new EU members and their neighbours to the east, while developing stronger links to the new emerging economies in Asia and improving trans-Atlantic relations. In the context of international security, the Armed Forces will have to acquire greater capacity and resources to successfully complete its missions in conflictive areas such as Afghanistan and Pakistan. Along with international terrorism, key items on the future international agenda will include illegal immigration, energy policy and climate change. In order to respond to all of this in an effective and responsible way, it will be essential to develop a proactive European policy and to consolidate the Spanish position by updating treaties and agreements.

4. Conclusions

To recognise how much has been achieved is not simply to give wings to vain triumphalism; rather, it is essential to meeting the challenges of the future. Given the simultaneous challenges we face today, including phenomena such as economic globalisation, demographic and social change, environmental pressure and the new security conditions that prevail at the international level, it should serve to stimulate optimism and confidence to take note of where things stood in 1986, when the final phase of the long historical process of Europeanisation began, and to see how far we have progressed.

Rising GDP and per capita income over the past two decades, the successful control of inflation, public deficit and debt, dropping unemployment and the opening up of the Spanish economy to the outside world are some of the most visible indicators of the success of Spain’s integration in the EU, a process in which EU funds have played a key role. But the process of real convergence has also taken place at the socio-political level, with the modernisation of the structures of public administration and of social values, and with the rise of Spain’s military, diplomatic, economic and cultural profile in the world. Spain has become greatly Europeanised, but has also helped enrich the Mediterranean and Latin American dimensions of the EU, and has helped develop the Union’s economic and social cohesion, European citizenship and the Space of Freedom, Security and Justice.

The balance of 20 years of Spanish integration in the European Union should be a cause for satisfaction for Spaniards and Europeans alike. Spain’s success is one more indicator of the success of the European project. At a time when Europe has lost its sense of direction and seems unable to satisfactorily face the double challenge of ‘enlargement + constitution’, the Spanish example should serve as a reminder of all that can be achieved when Europe is working well and its societies feel involved in the European project. Modern Spain cannot be understood without Europe and Europe should see itself reflected in this success and look to the future with confidence.

Sonia Piedrafita

Researcher at the European Institute of Public Administration (EIPA, Maastricht)

Federico Steinberg

Professor at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid and Analyst at the Elcano Royal Institute

José Ignacio Torreblanca

Professor at the UNED and Senior Analyst on Europe for the Elcano Royal Institute

[1] This article was published in Política Exterior magazine (nr 118, vol. XXI, July/August, p. 153-67). It is an updated summary of the book 20 años de España en la Unión Europea (1986-2006) by Sonia Piedrafita, Federico Steinberg and José Ignacio Torreblanca (Elcano Royal Institute and the European Parliament, 2006). The book is available in Spanish and English.