At some point this year, Spain’s population will reach 50 million, having grown more than 14 million over the last half century, the largest increase among the five biggest EU nations in relative terms (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Population growth, 1975-2024 (million)

| 1975 | 2025 (1) | Absolute change | % change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | 54.0 | 68.6 | + 14.6 | +26.8 |

| Germany (2) | 78.7 | 84.1 | +5.4 | +6.8 |

| Italy | 55.4 | 59.0 | +3.6 | +6.3 |

| Poland | 34.0 | 38.1 | +4.1 | +12.0 |

| Spain | 35.7 | 49.4 (3) | +13.7 | +38.3 |

The surge in population is almost entirely due to net international migration and not to an increase in the native-born population. Not that many decades ago, Spain was a net emigration country.

The country’s fertility rate plummeted from 3 in 1964 to 2 in 1981 and to 1.2 in 2025, one of the lowest in the world and far short of the 2.1 at which existing population levels would be maintained. In 1996 the United Nations forecast the total population would sharply fall by 2050 from almost 40 million to 28-30 million unless trends changed. They did and significantly: the foreign-born population surged from 542,314 in 1996 (1.4% of the total population) to 9.8 million in October 2025 (19.8%, higher than France and Italy and comparable to Germany, see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Share of foreign-born persons in the resident population of EU countries, 1/I/2024 (%)

| Country | % |

|---|---|

| Luxembourg | 51.0 |

| Ireland | 22.6 |

| Sweden | 20.6 |

| Germany | 20.2 |

| Spain (1) | 19.8 |

| France | 13.6 |

| Italy | 11.3 |

| EU | 9.9 |

| Poland | 2.6 |

The first influx of immigrants took place between 1995 and 2008 during Spain’s infrastructure and property boom, fuelled by cheap euro borrowing, low interest rates and lax lending by banks. An ageing population –Spain’s average life expectancy has risen from 73.3 years in 1975 to 84 years– and a dwindling ‘native’ labour force opened up numerous jobs for immigrants until the global financial crisis and the real-estate crash.

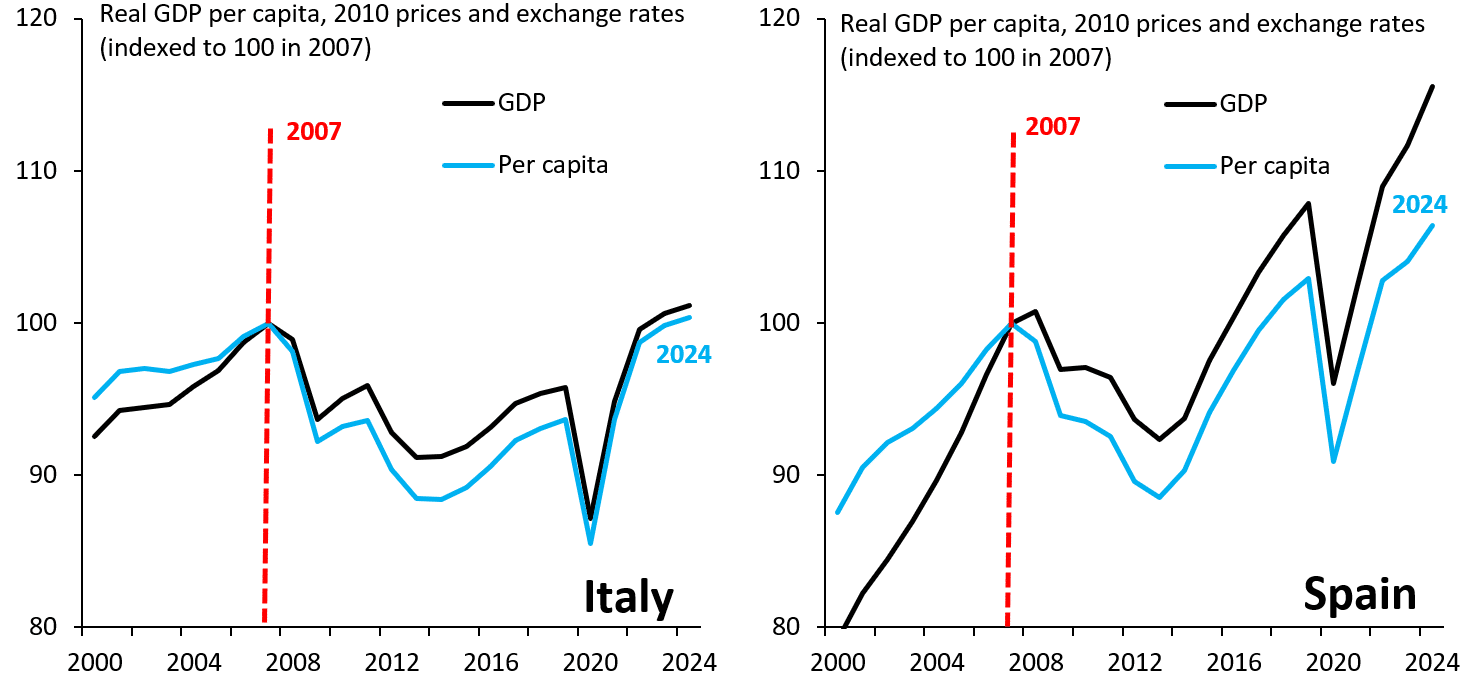

The flow of immigrants dried up between 2009, when Spain went into a deep recession, and 2017, as Spain grappled with very high unemployment. But a second influx began as of 2018, despite the devastating impact of COVID, intensifying after 2022. The foreign-born population has increased by more than 1.6 million since then and is powering an economy, which has been growing at more than double the euro-zone average. Headline GDP growth is strong, but per capita GDP growth is weak due to massive immigration boosting the population and other issues such as low productivity (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Italy & Spain: real GDP per capita, 2010 prices and exchange (indexed to 100 in 2007)

Foreign workers now make up 14.4% of total employment (based on those contributing to the social security system), filling 44% of new jobs in 2025, according to the OECD’s latest report on Spain. The labour force participation rate of foreigners is almost 70%, much higher than the 56.4% for Spain as whole. The working population has risen by two million since 2020 to just over 25 million, a bigger increase than between 2005 and 2020, and the unemployment rate has come down from 16% in 2020 to an albeit still high 11.4%. Foreign workers contribute 10% of the social security system’s revenue and are responsible for 1% of its costs, according to a recent report.

Migrants in a country with a rapidly ageing population are supporting key sectors such as the vital tourism industry (around 97 million international tourists in 2025, close to double the population), agribusiness, an important exporter, social care and construction (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Employment by nationality and sectors, 2024 (%)

| Spaniards (1) | Foreigners (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | 3.1 | 5.7 |

| Industry | 13.8 | 10.7 |

| Construction | 6.0 | 10.9 |

| Services | 77.1 | 72.8 |

Estimates vary, but all projections, on current trends, point to a big increase in the old-age dependency ratio. The statistics institute INE projects there will be just 1.2 people of working age for every person over the age of 65 in 2050 compared with the current 2.6.

Such a demographic shift, unless countered by migration, will reduce labour supply, slow potential output growth, weigh on government and public services with an ageing civil service, and place growing pressures on public finances, particularly the pay-as-you-go pension and healthcare systems. The fiscal watchdog AIReF estimates that total public spending related to ageing will rise from 20.3% of GDP in 2022 to 25.5% in 2050, an increase of 5.2 pp compared with 1.5 pp for the EU as a whole.

Over the past 25 years Spain has become, like many other EU countries, a much more diverse society. Spain has more Latin Americans (4.2 million in 2024) than the rest of the EU together (around 3 million). Latin Americans bring with them the Spanish language (except for Brazil) and, generally, the Roman Catholic religion, easing their integration into Spanish society. While assimilation has been largely successful, it is striking how very few MPs in Spain are foreign-born (only 45 of the almost 4,000 MPs between 1993 and 2023), far lower than the UK, the Netherlands and Germany, according to a study by Proyecto Repchance.

Most Latin Americans do not need a visa to come to Spain and the process for them for obtaining Spanish nationality is easier than for other countries; 45% of these immigrants have already acquired Spanish nationality. Their level of educational attainment is generally low, but higher than that for immigrants from Asia and Africa. Those with a higher educational attainment such as lawyers, doctors and engineers find it more difficult to get a job because of the long time it takes to get their professional qualifications officially validated.[1]

Of those who do not have Spanish nationality, the largest country group is from Morocco, followed by Romania (see Figure 5). Moroccans, because of language and cultural issues, have not assimilated as easily. Romanians, on the other hand, pick up Spanish quickly as both languages are descended from Vulgar Latin.

Figure 5. Ten largest foreign nationalities, at 1/I/2025 and 1/I/1996 (1)

| Number in 2025 | % of total | Number in 1996 | % of total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morocco | 968,999 | 14.0 | 111,043 | 17.4 |

| Romania | 608,270 | 8.8 | 2,258 | 0.3 |

| Colombia | 676,534 | 9.8 | 9,997 | 1.6 |

| Venezuela | 377,809 | 5.5 | 16,549 (2) | NA |

| Italy | 345,777 | 5.0 | 19,287 | 3.0 |

| UK | 266,462 | 3.9 | 75,600 | 11.8 |

| China | 238,372 | 3.4 | 11,611 | 1.8 |

| Peru | 260,544 | 3.8 | 928 (2) | NA |

| Ukraine | 202,105 | 2.9 | 727 (2) | NA |

| Honduras | 177,929 | 2.6 | 795 (2) | NA |

| Total of all nationalities | 6,911,971 | 100.0 | 637,085 | 100.0 |

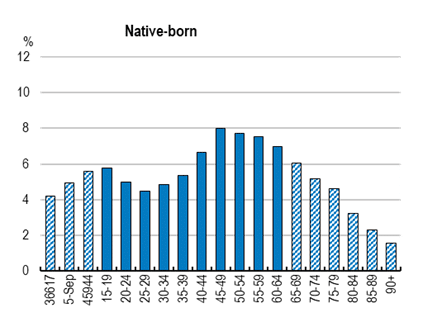

Immigrants are improving the shape of Spain’s population pyramid, mitigating the ageing of the population and helping to secure pension sustainment (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Age distribution of the native- and foreign-born population, 2024

While polls show immigrants are viewed as playing a positive role in powering the economy (see Figure 7), they also present challenges and the need for greater long-term planning.

Figure 7. Positive aspects of immigration by age groups (%)

| 18-24 | 25-34 | 35-44 | 45-54 | 55-64 | 65-74 | 75+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contribution to economic growth | 46.0 | 35.0 | 32.8 | 42.9 | 42.8 | 46.7 | 39.1 |

| Enrichment of Spanish culture | 5.5 | 9.3 | 10.2 | 7.8 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 1.3 |

| Favouring demographic sustainability | 19.1 | 23.2 | 22.7 | 17.2 | 21.7 | 14.2 | 10.1 |

| Guaranteeing pension sustainment | 6.8 | 11.1 | 12.5 | 16.7 | 18.2 | 16.5 | 22.8 |

While by far the main negative aspect of immigration for young adults (18-24-year olds) is greater insecurity (see Figure 8), which is more perceived than real as Spain is a relatively safe country with low violent crime, the main concern for those aged 45 to 74 is the greater pressure on public services, according to a report by Opina360.

Figure 8. Negative aspects of immigration by age groups (%)

| 18-24 | 25-34 | 35-44 | 45-54 | 55-64 | 65-74 | 75+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greater insecurity | 40.0 | 34.3 | 28.2 | 26.4 | 23.7 | 20.0 | 27.9 |

| Greater pressure on public services | 17.0 | 21.3 | 24.1 | 27.1 | 25.9 | 26.9 | 17.7 |

| Loss of cultural identity | 13.6 | 15.8 | 10.9 | 10.8 | 12.0 | 12.6 | 15.2 |

| Saturation of housing market | 12.4 | 14.8 | 11.8 | 12.9 | 15.4 | 15.0 | 22.9 |

The insecurity issue is linked to the sharp increase in young adults supporting the hard-right, anti-immigrant VOX, which plays up insecurity with little evidence. Only 7% of respondents identifying themselves as on the left said insecurity was greater, compared with 50% on the right.

Meanwhile, the concern over pensions and the public health system can be seen in the context of older people moving towards retirement. Spain’s 1960-1975 ‘baby boom’ came more than a decade later than in most other European countries.

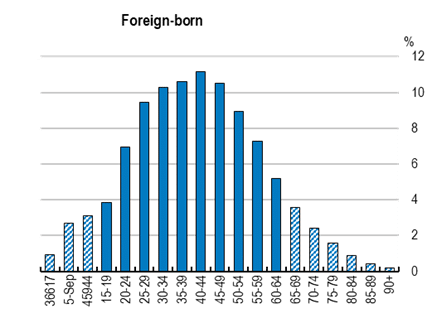

One of Spain’s most pressing social problems is the lack of new affordable housing, an issue aggravated by the need for immigrants, as they, too, need homes. The supply of properties cannot keep up with the influx of new arrivals, let alone with the resident population. Approximately 140,000 new households are created each year but only around 80,000 new homes (see Figure 9). The situation today is a far cry from that in 2008 before the crash of the massive housing boom when there was a huge oversupply of properties. In 2006 the number of housing starts (664,923) was more than that of Germany, France and Italy combined.

Furthermore, Spain’s stock of social rental dwellings (2.5% of the total housing stock compared with an EU average of 9%) is the lowest among the 38 OECD countries. The housing bottleneck raises questions over whether immigrant arrivals can continue at the current pace. Yet without immigrants Spain would over the next decade have many unfilled job vacancies.

Figure 9. Spain: housing completions vs new households (accumulated, thousands)

The OECD points out that there are an estimated 3.8 million empty properties, but they are mostly located in places where people do not want to live because job prospects are limited and basic services and amenities are not close at hand. One-third of empty properties are in towns with fewer than 1,000 inhabitants and only 18% in cities. The Roman Catholic Church has unused buildings and the Ministry of Defence empty barracks and land that could be used for housing.

The vast majority of immigrants live in or near cities. The population of the Madrid region has increased by more than 1.8 million since 2005, followed by Barcelona province (+1.2 million), Alicante (+600,000) and Valencia (+562,000), while the population of the provinces of Orense, Zamora, Lugo and León and the region of Asturias, which are part of ‘emptied out’ Spain, has dropped by 211,000. The gap between ‘emptied out’ and ‘saturated’ Spain is widening.

Housing has become so expensive in cities such as Madrid and Barcelona that salaried workers are moving out to cheaper areas, such as Toledo and Guadalajara in the former case and Gerona and Tarragona in the latter. The Tax Agency said 237,000 workers changed homes in 2024, up from 166,000 in 2019 before the COVID pandemic.

The demographic issues in the broadest sense need to be tackled through a pact between the main political parties, but in today’s Spain with its deeply ideological differences that, sadly, is a pipe dream.

[1] See Carmen González Enríquez & José Pablo Martínez (2025), Immigration and the labour market in Spain (II): Latin American immigration, Elcano Royal Institute, 17/XI/2025.