On 28 June 2013 the Shah Deniz Consortium (SDC) took a historic decision that put an end to a decade-long pipeline race to bring Central Asian gas to Europe. SDC, led by BP, decided that the surplus natural gas produced in the Azerbaijani Shah Deniz II field was to be transported to Europe through the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP). The big loser was Nabucco, a project that the European Commission once considered ’strategic’ for the opening of the Southern Gas Corridor.

Nabucco was to open the Southern Corridor, one of the six strategic and priority infrastructure actions proposed to ensure that the EU’s gas needs are met by 2020, thus ensuring Europe’s security of supply by diversifying both suppliers and routes. However, Nabucco was never the only option on the table, and its viability was always contested.

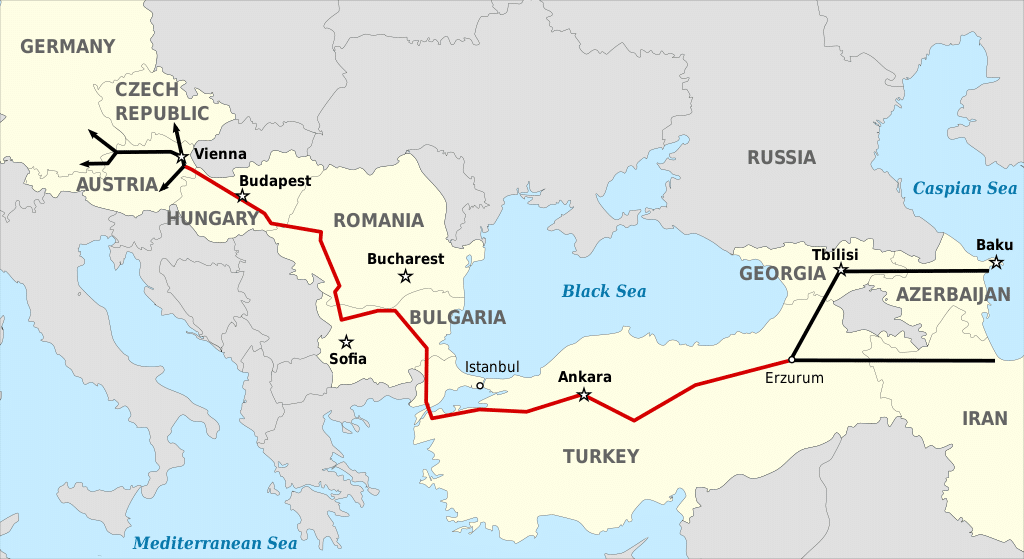

In order to make a decision, SDC took into account seven main areas: market opportunities, timing, scalability, management operability, funding availability, project quality and transparency. Although the evaluation undertaken by SDC is not available to the public, its decision was taken following both economic and political rationales. A brief analysis shows that TAP has a few economic advantages over Nabucco West, while not challenging very much the geopolitical status quo and its implications for the big energy players like Russia. It should be borne in mind that Nabucco West was the heir to Nabucco’s initial proposal once Turkey and Azerbaijan reached an agreement for the construction of the Trans-Anatolian Gas Pipeline (TANAP) at the end of 2011. Only after Nabucco’s initial proposal was ‘downgraded’ to Nabucco West, were the TAP and Nabucco proposals comparable.

In economic terms, TAP has the whip hand. With a similar capacity, TAP’s estimated construction costs are lower than Nabucco West’s mainly due to its shorter route. TAP’s main destination market is Italy, where natural gas is sold at a higher price than in Austria. Furthermore, the demand for gas in Italy in absolute numbers is expected to grow over 2.5 times more than in Austria by 2030. Finally, any gas surplus can be transported farther into Europe and re-sold from either Italy or Austria.

In political terms, TAP has some advantages and poses fewer inconveniences than Nabucco West. TAP has as much strong governmental support from the countries it transits as Nabucco. As a European project, the European Commission (EC) also supports TAP and can therefore claim success in opening the Southern Corridor. While as a project Nabucco generated a bitter rivalry with Russia’s Gazprom, TAP has generated fewer concerns in Russia, Europe’s largest gas supplier. That is so because TAP is less of a competitor for Gazprom’s exports to Europe, while it remains physically within the EU’s borders. Finally, TAP will bring gas to Italy, a country with quite well-diversified gas suppliers, whereas Austria is highly dependent on Russian gas: around 50% of Austria’s gas imports come from Russia, while Italy imports less than 30% from Russia. Had Nabucco been constructed, Austria’s dependence on Russian gas would have fallen significantly, while TAP does not change Italy’s dependence on Russia very much.

| Key features / Pipeline | Nabucco-West | TAP | TANAP | Nabucco | South Stream |

| Length | 1329 km | 867 km | 1700 km | 3893 km | 2380 km |

| Capacity | 10-23 bcma | 10-20 bcma | 16-31 bcma | 31 bcma | 63 bcma |

| Estimated cost | €2.7 billion (own estimate) | €1.5 billion | €6.7 billion | €7.9 billion | €16 billion |

| Construction to begin in | – | 2015 | 2014 | – | 2012 |

| Gas to be delivered by | – | 2019 | 2018 | – | 2015 |

| Transit countries (Main destination market) | Bulgaria Romania Hungary (Austria) | Greece Albania (Italy) | (Turkey) | Turkey Bulgaria Romania Hungary (Austria) | Russia Bulgaria Serbia Hungary Slovenia (Italy) |

| Partners / Owners | OMV (24%) MOL (17%) Transgaz (17%) Bulgargaz (17%) BOTAŞ (17%) GDF (9%) | BP (20%) SOCAR (20%) Statoil (20%) Fluxys (16%) Total (10%) E.ON (9%) Axpo (5%) | SOCAR (80%) BOTAŞ (15%) TPAO (5%) | OMV (17%) MOL (17%) Transgaz (17%) Bulgargaz (17%) BOTAŞ (17%) RWE (17%) | Offshore section: Gazprom (50%) Eni (20%) EDF (15%) Wintershall (15%)Onshore section: National joint ventures in Austria (OMV), Bulgaria (BEH), Croatia (Plinacro), Greece (DESFA), Hungay (MVM), Serbia (Srbijagas) and Slovenia (Plinovodi), all controlled by Gazprom (at least 50% of shares) |

Nabucco was born as a mega-project: quite big, very ambitious, with a large budget and engaged at a very high political level. It was soon contested by another mega-project, Russia’s South Stream. Nabucco always had the strong political support of Austria, the other European transit countries and the EC. It was a flagship project, a symbol of the EC’s determination to reduce Europe’s gas dependence on Russia and of Austria’s desire to become a major player in the gas game. The project seemed too big to fail. The EC had supported it for too long for anyone to think it would let it go. However, Nabucco’s main challenge came not from politics, but from geo-economics. Despite enjoying political support, the project never had access to a gas source. As Vladimir Putin put it, the question was never whether it would be possible to build the pipeline but whether it could be filled. Nevertheless, it must be borne in mind that Nabucco was never intended to own or buy gas, only to sell transport capacity to producers.

Austria’s OMV, the leading company behind Nabucco, also failed to understand the game of alliances and common interests being played by the other actors. OMV may have been too naïve, trusting that the greater good would prevail over commercial assessments. Nabucco remained mostly a Central and Eastern European project led by OMV, with the aim of bringing Azerbaijani gas to the Central European Gas Hub in Austria, a distribution hub also controlled by OMV. The Austrian company was competing against BP and Statoil, respectively one of the biggest ‘seven sisters’ and one of the biggest national oil companies.

TAP, on the other hand, managed to establish close alliances with key players in the year prior to SDC’s final decision. TAP partnered with TANAP, the ‘killer’ of the original Nabucco project, and therefore with its main shareholder, the State Oil Company of the Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR), which was also the owner of 10% of SDC. Later on, TAP offered SDC’s shareholders the possibility of buying TAP shares. By June 2013, the interests of SDC’s major stakeholders were in line with TAP’s. By the time SDC’s decision was made (June 28) there was not a single SDC shareholder investing in Nabucco West, but as early as 30 July 2013 BP and SOCAR joined Statoil to collectively own 60% of TAP and 61% of SDC.

The EU’s need to import gas will increase over time, as demand is expected to rise and domestic production is expected to decline. One of the EC’s goals to meet this increasing demand is to open the Southern Corridor. For the EC, whether the gas from the Caspian Sea flows to Europe through TAP or Nabucco is irrelevant, since the aim is to enhance the security of the EU’s energy supply. TAP/TANAP will open such a route, meeting the EC’s goal.

However, TAP will only make a small contribution to enhancing the EU’s security of supply. With a capacity of 10 to 20bcma, TAP is expected to provide 2.29% to 4.58% of the EU’s projected gas imports by 2030 (or 12.26% to 22.32% of Italy’s gas imports). Hence, the EC continues to point out the need for future developments and projects to diversify both routes and suppliers in order to meet the EU’s gas demand. Thus, new projects will be sought to take gas from the Caspian Sea and the Middle East to Europe. BP, for instance, has not closed the door to a second pipeline to transport Azerbaijan’s gas to Europe. Other projects, such as Russia’s South Stream, will also contribute to meet the EU’s gas demand.

Some scholars have criticised the EC’s apparent lack of initiative during the selection process. The EC limited its action to setting high-strategy objectives and left the final decision in the hands of political and economic actors. This laisser-faire strategy allowed national actors and private energy companies to decide on the basis of economic and national interests. However, the strategy also put into practice the principle of subsidiarity, which is one of the EU’s general principles. At the same time, it prevented less economically-powerful and more dependent countries in Central and South-Eastern Europe from diversifying their suppliers, thus jeopardising the EU’s principle of common solidarity. Only the future will tell if the trade-off was worth the effort.

To sum up, Nabucco struggled to become a reality for a decade. Backed by the EC, Nabucco’s biggest rival seemed to be Gazprom’s South Stream. Ultimately, Nabucco was not defeated by the Russian giant but by its inability to secure a gas source and involve those who had it. Whereas OMV succeeded in bringing together the different governments of the transit countries and gained the EC’s support, it failed to align its interests with those of the Azerbaijani government and SOCAR or other members of SDC, including BP and Statoil. Through discrete but effective moves, TAP was able to succeed where Nabucco failed. The presence of Statoil in both TAP and SDC since the beginning may have helped to smooth out the alignment process, an advantage that Nabucco did not have.

Europe will continue to import gas for decades to come and a good diversification of suppliers and routes is essential for its security of supply. However, the EU does not have a strong energy policy. Most European States consider energy an issue of national security and therefore refuse to let Brussels control energy matters fully. TAP’s triumph over Nabucco is an example of private business motivations and national actors pursuing national interests. Scholars dealing with energy issues in Europe often forget about the truth of this competition. Although the political implications surrounding the opening of the Southern Corridor are clear, neither the EC, Italy or Austria made the final decision, and it was SDC that did so. Whether any national government influenced the decision is another story.