The US Treasury and the Argentine government have taken another step towards finalising the financial support package. The main development was the ratification of a $20 billion currency swap between the Treasury and the Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA), and the announcement that the Treasury will intervene directly in the local currency market by selling dollars for pesos –as it did last week– to stabilise the peso, and possibly also in the Argentine global bond market.

At this stage of the plan, clinging to firm convictions that were highly applicable at the outset can be counterproductive. It is important, following the agreement with the IMF, to acknowledge that not everything went as planned and to understand what went wrong.

Details of the operational use of the funds are still pending, and the anticipated meeting between Presidents Donald Trump and Javier Milei did not help to clarify matters, but rather added a dose of confusion by making aid to Argentina conditional on an electoral victory for Javier Milei, without it being clear what “victory” would mean in the case of midterm legislative elections in which half of the Chamber of Deputies and a third of the Senate are up for re-election.

If it materialises, will this additional injection of international liquidity –on top of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) disbursement of a similar amount in April– be enough to rescue the plan? It is a necessary condition; it is unclear whether it will be sufficient. Creating circumstances that will enable it to be so is the government’s great challenge once the midterm elections are over. Time will tell.

Agreement with the IMF: not everything went according to plan

When Javier Milei took office in December 2023, he inherited a very high fiscal deficit, rampant inflation and a stagnant economy plagued by distortions. In addition, the BCRA’s international reserves –net of short-term obligations– were negative by some $11 billion, despite exchange controls and currency rationing. In plain language: the country did not have the resources to meet its obligations and was technically bankrupt.

The response was a shock stabilisation plan. Its initial achievements –balancing of the fiscal books following a fast and furious adjustment, plunging inflation and a rebound in economic activity after an initial contraction– needed to be strengthened with an injection of liquidity to rebuild international reserves. The twofold goal was to lift the exchange rate restrictions smoothly and to lower country risk in order to regain access to international financial markets. If successful, this would unlock latent investments in mining, energy, renewables, agribusiness and technology, putting the country on the path to stability and growth. On the basis of such logic, a $20 billion programme was agreed with the IMF and approved on April 11.

The first objective was achieved: the exchange controls were lifted without turbulence. The dollar stabilised at between 1,100 and 1,300 pesos, close to the central range of the floating band –initially 40%– agreed with the IMF. The injection of IMF resources raised gross reserves to about $40 billion –equivalent to 100% of the BCRA’s monetary liabilities in pesos– and country risk fell from 900 to 600 basis points (Figure 1).

Even so, the signal was not enough to bring country risk to levels compatible with voluntary financing –below 400 basis points– or to activate the expected virtuous circle of investment and growth. Why? An intellectually honest diagnosis is key to adjusting course. At this stage of the plan, clinging to firm convictions that were highly applicable at the outset can be counterproductive. It is important, following the agreement with the IMF, to acknowledge that not everything went as planned and to understand what went wrong.

Three non-mutually exclusive hypotheses

a. Hypothesis 1: interest rates and the exchange rate are out of equilibrium

An excessively low exchange rate –maintained by unsustainably high interest rates in pesos and, more recently, by Treasury sales in the foreign exchange market– impairs the external current account and makes it difficult to accumulate reserves at the rate necessary to honour foreign currency debt in a timely manner (the BCRA’s gross reserves are US$8 billion below the IMF programme). Without growing reserves, the risk of default remains an ever-present threat, country risk does not ameliorate, international credit does not return, investments fail to materialise and the economy lacks the impetus to take off (Figures 2 and 3).

- Policy implication: eliminate the band and allow the peso to float so that the exchange rate can find its equilibrium. This involves gradually lowering interest rates to levels consistent with the programme –around 30–35% vs. the current 55%– as expectations of an abrupt devaluation subside, and reducing exchange rate intervention, which is likely to lead to a depreciation of the peso that facilitates an accumulation of reserves compatible with the IMF programme and payment obligations in foreign currencies.

- Risks: in an economy where the dollar is the unit of account and store of value, and with a very small peso-denominated financial system, interest rates are not an effective anchor for expectations. Without an anchor, there is a risk of destabilisation.

b. Hypothesis 2: the central problem is political

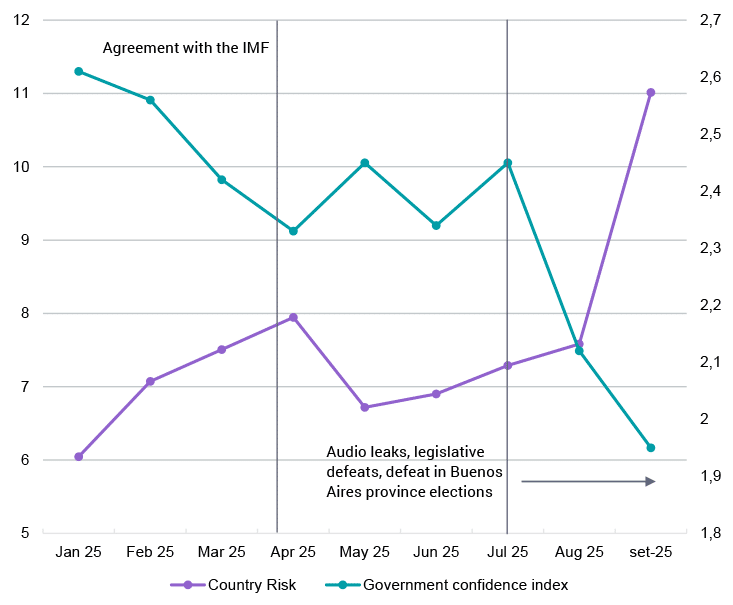

The defeat in the province of Buenos Aires was the visible symptom of a deeper erosion: distancing from Propuesta Republicana (PRO) –the centre-right party of former President Mauricio Macri– and from governors who had been allies of the government, presidential vetoes to preserve fiscal balance overturned by large majorities in Congress and suspicions of corruption in the president’s inner circle. The market saw this not as a temporary setback but as the erosion of the president’s political capital and the political coalition that supported the economic programme. As a result, confidence in the government fell and country risk skyrocketed, delaying Argentina’s return to international financial markets and stalling the arrival of investments (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Confidence in the government and country risk

- Policy implication: if the problem is political, the response must be political. At a minimum, once the results from the October election are known, a working coalition must be rebuilt to sustain fiscal balance and enable the reform agenda set out in the programme with the IMF. In the most optimistic scenario, a disruptive option should be considered: a basic minimum pact with the opposition that offers predictability to creditors and investors.

- Risks: the search for broad consensus may dilute reformist ambition and undermine its effectiveness.

c. Hypothesis 3: international liquidity deficit

The IMF’s resources are sufficient to back the BCRA’s monetary liabilities in pesos and defend the band, but not to simultaneously guarantee the repayment of the most imminent foreign currency obligations. Without that certainty, the risk of default persists, country risk does not fall sufficiently and access to markets remains unrestored. The country is caught in a bad equilibrium: it possesses good prospects for strategic investments and exports, but in the absence of liquidity to meet immediate maturities and with high country risk, investments fail to materialise and growth does not accelerate; without growth, honouring debts becomes challenging.

- Policy implication: in addition to the IMF’s liquidity contribution, an additional injection of external liquidity is required to cover short-term foreign currency obligations and avert the risk of default. With such reinforcement, the BCRA and the Treasury would have the strength to defend the exchange rate band while ensuring the repayment of obligations, reducing country risk and unlocking private financing, investment inflows and growth.

- Risks: this is the prevailing hypothesis within the economic team today –and the present author is largely in agreement with it– but the main risk involves adhering to it blindly. After all, despite its magnitude, the IMF programme did not succeed in restoring Argentina’s access to bond markets.

The Policy Mix

It is plausible for elements of all three hypotheses to be successfully combined. If, after 26 October, additional assistance from the US Treasury also fails to lower the country risk to levels that allow access to bond markets, a rethink will be necessary (Figure 1).

The most effective strategy for decisively influencing expectations is not to choose a single lever, but to activate all three simultaneously and coherently.

- On the exchange rate and monetary front: bring domestic interest rates in line with the programme’s objectives — not only by reducing the BCRA’s policy rate, but also gradually ceasing to validate exorbitant interest rates to refinance Treasury debt in pesos — and allow the exchange rate to find its equilibrium. This can be done without losing the programme’s anchor or stability, because the firepower in foreign currency will be much greater with the Treasury’s assistance.

- On the political front: rebuild a coalition that restores the government’s initiative, shields fiscal balance and enables the IMF programme’s reforms to be implemented. The outcome of 26 October will define the executive branch’s power in Congress. Assistance from the Treasury provides leeway to forge agreements without the pressure of the markets.

Recent signs point in the right direction. The US Treasury and the Argentine government are making progress on the operational details of financial assistance, while the US Treasury has already intervened in the currency market by selling dollars for pesos, in an unusual show of support. Politically, there are signs of rapprochement with old allies, although there is still no clear message against corruption, nor is there — and this is more unlikely — an opening for dialogue with the opposition to reach a basic economic agreement that would ensure a minimum of predictability. On the exchange rate front, there are no signs of a loosening of the band, but such decisions are usually made without warning.

Conclusion

Argentina still has time to rescue its stabilisation programme. To achieve this, it needs decisive and simultaneous action on three fronts: more international liquidity (already underway with the US Treasury, although details remain to be defined), an interest rate (and dollar price) that reflects the fundamentals of the programme, and a political architecture that shields the fiscal balance and makes reforms viable. This three-pronged offensive — the elements of which are not incompatible, but rather self-reinforcing — can align expectations, unlock financing and investment, and set the virtuous circle in motion.