On 9th March 2021, the European Commission released its newly Digital Compass: the first detailed document by which EU’s Digital Decade ambitions are translated into measurable, concrete, coherent targets towards the 2030 scenario. While it has not yet received large attention by the media, it happens to be a significant package, not only by the existence of a four-axis matrix, but especially due to the risks that it might convey if the proposed governance structure is not accurately set up in a coherent, cohesive manner. These risks refer to capabilities and policy, as well as to the need to maintain and building confidence and understanding measures amongst EU institutions and the very Member States. This is especially relevant with digitalisation, an issue which has not been fully spread out across all Member States’ institutional architectures –Ministries, Offices, National Strategies–, and it does not benefit from high levels of social acceptance and awareness in the same depth.

The Digital Compass has been released at an opportune time, but it needs to ensure that its mechanisms are part of a robust framework. To this end, this article analyses lessons drawn from limitations derived from other European mechanisms –such as the Strategic Compass, oriented to security and defence, or the EU’s 5G Toolbox. The goal is to propose courses for action so that the Digital Compass, alongside actionable measures, contains a solid governance structure based on checks and balances; fluid coordination between EU institutions and Member States’ likely different expectations and plans; policy coordination; and effective evaluation and monitoring from institutions, as well as other stakeholders which play a major role in digital transformation: civil society groups and corporations.

Towards a solid governance structure for a large set of ambitious plans

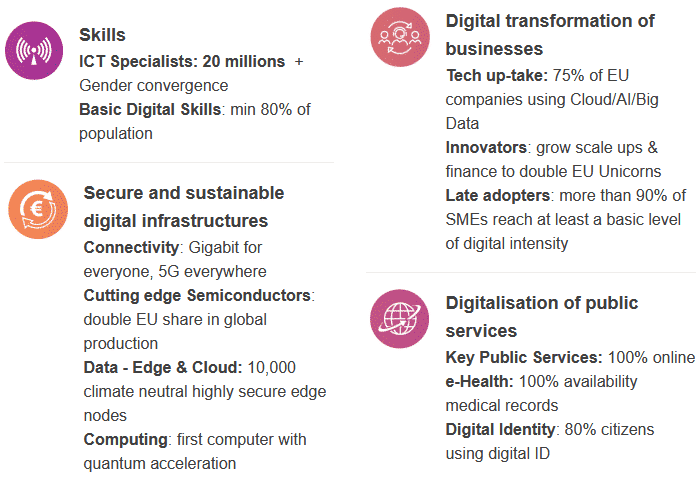

The first step is to define the “cardinal points” from this Digital Compass:

- A digitally skilled population and highly skilled digital professionals, with increased women’s presence.

- Secure, sustainable, and substantial digital infrastructures.

- Digital transformation of businesses.

- Digitisation of public sectors and services.

These four axes include a large set of highly ambitious goals, which in turn will lead to the activation, reactivation, or creation of new mechanisms to conduct them. The question might be whether these goals are realistic and feasible vis-à-vis the 2030 scenario. However, the most effective way to analyse the Digital Compass is to address the very effectiveness of the governance structure (top-down approach) in ensuring the implementation of each target and its interrelationship with other targets.

Digital Compass’ governance structure is based on a “3+1” approach: the first three are conceived as essential tools concerning the design, implementation, and evaluation of these one-by-one metrics within the EU; and the latter refers to the “driving factor” to internationalize these inward metrics. However, it is worth to mention that this Digital Compass barely refers to the “geopolitical dimension” of digitalisation. It should be addressed in the next steps, once the Digital Police Programme is operationalised by the end of the summer, and the Inter-Institutional Declaration on Digital Principles progresses by the end of 2021.

| Quantification of concrete goals by KPIs under the four cardinal points | Shaping and launch of Multi-country projects | Monitoring Digital Principles | International partnerships |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative monitoring of KPIs (Key Performance Indicators). | Monitoring of infrastructure and critical capacity gap.

Building consensus and fostering agreement on common projects and facilitating their implementation. |

Annual reports.

Scoreboards. Annual publication of the European State of the Digital Decade Report: progress towards the 2030 targets through a score of “traffic lights”. Annual Eurobarometer on social perception of respect for digital rights. |

Alignment or convergence with other countries on norms, regulations, and standards (normative power).

Digital economy packages and international agreements through digital-related funds. |

Source: the author (2021).

Recommendations for improvement

This governance structure promotes the guardianship over all targets from its design and implementation to its evaluation and accountability. However, for this framework to be solid, effective, and sustainable in the long run, there are a set of risks to be overcome:

- Axes and specific metrics cannot be addressed through the same model of governance. Building upon OPSI-OECD Anticipatory Governance Models, each measure should be seen as an own governance which is intertwined with targets from all axes.

There are four main innovation models which might be differently applied, depending on two variables. First, depending on the audience concerned by each target and which stakeholders should be on board (if it is addressed to EU institutions, Member States’ architecture, or the very citizenship or corporations). Second, it also relies on the category of “target normality”: this is, if a measure has been previously deployed or is, at least, well known; or if it is a disruptive, uncharted issue for the EU –such as the expected first-ever quantum computer at the EU level by 2030, although a Quantum Flagship has already existed in the EU since 2018. Four innovation models are:

-

- Mission-Oriented Innovation (top-down, formulate).

- Anticipatory Innovation (exploring new radical, disruptive issues).

- Adaptive Innovation (bottom-up, responding to existing policies which must be intertwined for the first time).

- Enhancement-Oriented Innovation (exploring new topics, while incrementing its potential).

- From a geopolitical perspective, the Digital Compass must avoid committing the same risks that previous mechanisms have already experienced:

-

- Digital sovereignty should have a more delimited definition, which in turn intertwines both internal sovereignty (single market, normative power, capabilities) and foreign action (whether competences are shared or exclusive between the European External Action Service and the Commissioners on Competition and Single Market).

-

- The document talks on multi-country projects to facilitate Member States’ cooperation (in policy), but the Digital Compass should work as well towards politically confidence-building measures amongst Member States to make the Digital Compass an EU-wide whole-of-government guiding thread for all decision-making processes that might be taken concerning digitisation politically and geopolitically. Digitisation is part of more and more countries’ national strategies and of the EU-wide policy, but it has not acquired the same level of development on the “political” dimension –which largely differs from the policy world.

The goal is to avoid the same results derived from initial negotiations on the Strategic Compass –on security and defence. In this case, Member States faced great divergences when trying to define an EU-wide threat mapping. In the digital policy/political world, each Member State has different priorities and capabilities. Understanding, confidence-building measures, and political information-sharing culture will be essential to turn the “digital policy” into actual “politics on the digital” as a permanent process under the Digital Compass.

-

- There should be a greater focus on digitisation as a common good which looks forward to the development of Sustainable Development Goals, or other measures such as humanitarian technologies and civil society’s participation. The Digital Compass should “geopolitise” the European External Action Service, across all layers, Directorate-Generals, and departments. This might lead to fewer delays in project implementation, as it has already happened with the EU’s 5G Toolbox: although countries had similar policy governance structures (regarding instruments; not objectives, criteria, or mandate), each Member State had differing geopolitical visions on the issue, what has delayed the scope and level of deployments.

In conclusion, the recently released Digital Compass offers valuable opportunities, goals, and metrics because it shapes the minimal and maximum limitations concerning policy as such. This helps the EU and its Member States to restrict the digital pathway in a cohesive, coordinated manner. However, its governance structure (its umbrella) should reinforce the geopolitical and political outlook. This is especially relevant when it comes down to promoting effective decision-making processes, alleviating possible divergences amongst Member States and European institutions, and achieving a more precise definition –since the beginning- of capabilities and metrics, but especially of confidence measures and common threat mappings, without delays in the very definition of strategies as well as the implementation of digitisation as foreign policy.