The Popes, as noted by various scholars, have –or have had– their own ideas about God. Political leaders, especially those with a geopolitical sense, have different maps of their countries or their surroundings inside their heads. What map does Putin have in mind? It would be important to know… and there are certain indications. By contrast, the Europeans –the EU– do not appear to have a map in their heads, as they are not even clear about the limits of either the EU or NATO.

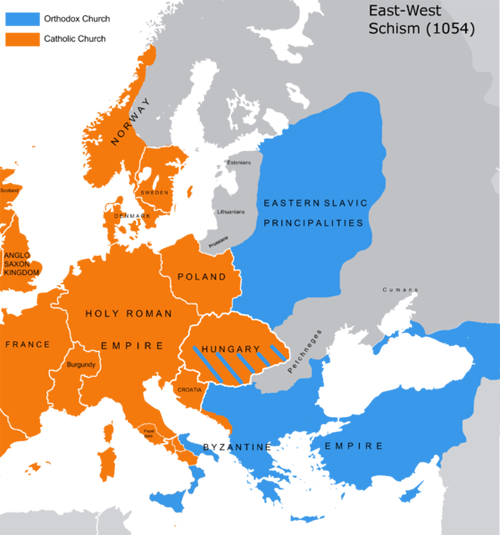

Around, or in, the Ukraine a map struggle is raging. This is the border that has separated Europe for nearly a millennium: the dividing line between Roman Catholic (and later also Protestant) and Orthodox since the Great Schism 1054 when the Roman Pontiff –who must have had maps in its head, although the wrong ones– excommunicated the Patriarch of Constantinople, Michael Cerularios.

This is the line which later became blurred by the advance of the Ottoman Empire. But it is the same one that Robert Kaplan so well analysed some time ago and which in our own times has marked the divisions of the Cold War –a war that was a meeting of maps, as drafted at Yalta– and the fratricidal war in the Balkans in the 1990s. It is the dividing line that has led Catholic Croatia into the EU, although it is to be hoped that Orthodox Serbia might finally join in what could be a historic reconciliation. For the EU can be instrumental in overcoming this ancient barrier, even if the Ukraine’s entry into the Union cannot be considered at present.

In the Ukraine the line divides the country into two parts –although the situation is actually more complicated, because there are mixed population areas–, Catholic and pro-Western on one side and Orthodox and pro-Russian on the other. Hence, events in the Ukraine’s eastern regions can be highly flammable and Moscow could easily lose control.

In its 11th edition, dated 1914, the Encyclopedia Britannica allotted the Ukraine just small paragraph: ‘(“frontier”), the name formerly given to a district of European Russia, now comprising the governments of Kharkov, Kiev, Podolia and Poltawa. The portion east of the Dnieper became Russian in 1686 and the portion west of the river in 1793’.

Nothing more. Someone must have protested because supplementary volume nr 32, published in 1922 –after the First World War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire–, devoted almost two pages to the entry, providing a much broader and more complex view. The story, of course, does not end there, because the borders of the Ukraine continued to change following the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of 1939 and all later events until today. This included the handover in 1954 of Crimea to the Ukraine by the Ukrainian Nikita Khrushchev, who would not have been too worried about the Soviet Union’s internal map of the Soviet Union because everything was fully under control. But there again is the historic boundary of 1054 causing trouble. Meanwhile, everyone is staring at the map, or rather his own map.

In a recent article in Foreign Affairs (‘Putin’s brain’), Anton Barbashin and Hannah Thoburn tried to imagine looking into Putin’s brain to see what map of Russia and its neighbourhood was lodged there. Is it the 1054 map? Or the 1914 version, in which the Russian Empire connected the Baltic to the Black Sea? That one would be dangerous. Or is it the Soviet Union and Europe in 1989, which is impossible to revive, when Gorbachev had in mind a map of a ‘common European home’? What is clear is that Putin is wary of ending up with the map of 1992, following the collapse of the USSR or –as he considers it– ‘the greatest geopolitical disaster of the 20th century’. He sees a Russia surrounded by unsympathetic powers and he wants to avoid having a hostile border. But in order to re-draw a map on the basis of concentric circles, given the faulty outcome of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), he has come up with the idea of a ‘Eurasian Union’ –replicating the EU model but with a disproportionate weight for Russia itself, given its size. This could be a materialisation of his mental map by other means, based on influence more than presence but focused on the ‘Russian world’ that he is somehow trying to reconstruct. And if that is the case, it will affect reality but he will not invade the Ukraine, seeking instead an accommodation on the lines of the agreement reached in Geneva last week.

Putin’s idea of Russia and the concept of Eurasia owe much to the inspiration and support of the (Russian) Orthodox Church, as do his condemnation of the Pussy Riot protest group and of homosexuality. The idea of Russia and Eurasia has been promoted by the radical nationalist Alexander Dugin, as discussed in the article mentioned above. Nevertheless, as noted by Jos Boonstra, events in the Crimea and the Ukraine can leave Putin without Kiev, making his Eurasian project incomplete. It can do the same to the EU’s neighbourhood policy in the east. And what is also important for us is that, as Joseph Janning warns, it can also destroy the EU’s neighbourhood policy in the South. So all these maps are interdependent.

He might not admit to it openly, but Putin definitely seems to have a map in his head. This is in contrast to the EU, which does not even know what to do with Turkey –let alone with the Ukraine– and whose Member States, starting with –a not fully western– Germany, have different maps of Europe in their heads. Perhaps Obama has his own map, aimed at making Russia an isolated pariah State. But the US is ceasing to be a European power. Putin knows it and he has noted that the world map that includes us all is becoming de-westernised. The test has been the UN General Assembly’s vote on Crimea, in which abstentions have carried a considerable weight. And that is Putin’s mental map.