Key messages

- ‘NATO First’ presents immense value to European allies as Britain builds munitions and strengthens the fleet.

- The CyberEM Command leaves questions unanswered for cyber warfare.

- Britain’s future concepts appear a rediscovery of the Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) thesis.

Analysis

The UK’s latest Strategic Defence Review,[1] released by Sir Keir Starmer’s government in recent weeks, is strong on rhetoric but, as Joe Devanny rightly notes, remains ‘light on details’.[2] It is a review that promises ‘increased lethality’,[3] ‘NATO First’, an ambitious submarine-building programme and a reinvigoration of the defence industrial base across the 144-page document. Included among these is a new CyberEM command headquarters to address issues of cyber warfare and a ‘digital targeting web’ concept for war fighting as a whole.[4]

Yet it is also plagued by phrases such as ‘subject to economic and fiscal conditions’[5] and is argued to have been immediately undermined by the government’s own Spending Review, released only a week later, that clearly prioritised health spending above all, leaving a large question mark as to how such grandiose ambitions can be financially delivered. Indeed, outlets were quick to comment that the ‘small print’ of the funding is based on subsuming elements of intelligence service budgets and areas ordinarily under the purview of the Foreign Office to meet a claim of 2.5% of spending,[6] with real term increases an aspiration for the next Parliament, and growth in the current Parliamentary term forecast at only 0.7%.[7] This led to an accusation from the Opposition that the Chancellor Rachel Reeves ‘chose to use Treasury tricks to deceive us all’.[8]

1. The SDR and ‘NATO First’

In tune with the previous Conservative government’s Integrated Review of 2021,[9] the now Labour government’s defence review continues the theme in recognising the world’s changing security environment. The SDR states that the 2022 invasion of Ukraine was a ‘strategic inflection point’,[10] demonstrating the return of state-on-state conflict in irrefutable terms. A key step change to the SDR from its Integrated Review predecessor lies in a return to a ‘NATO First’ approach, although with the caveat that ‘NATO First does not mean NATO only’.[11]

Beyond this caveat –itself built on top of the economic circumstances caveat– the SDR’s favoured approach for ‘NATO First’ appears to be a rediscovery of the time-old British strategy broadly described as ‘offshore balancing’[12] dressed up in 21st century clothing. Viewing the SDR through the prism of offshore balancing in this respect serves to reaffirm Britain’s position as a ‘natural seapower’ as asserted by Andrew Lambert. The SDR could even be seen as recognition of what Lambert claims as a ‘generational opportunity to shift the policy balance towards the wider world… That means putting the sea at the centre of national policy…’.[13] This came with the broad commitment from Britain to the production of up to 12 new nuclear-powered submarines as part of the Royal Navy’s fleet,[14] clearly showing where the ‘NATO First’ priority lies, with the navy ahead of the army and air force. Although land and air warfare were addressed in the SDR, there can be no serious expectation that any force structure even remotely resembling the Cold War era British Army of the Rhine (BAOR) is to be resurrected.

The second area of the SDR that is likely to be of most interest to European allies across NATO (and non-member countries) is Britain’s desire to establish six new munitions production facilities across the UK,[15] addressing the fragility of relying on just-in-time international supply chains as experienced during the pandemic.[16] While on paper this is termed as an ‘always on’ pipeline for munitions,[17] the implication from the SDR is that the munitions are to be centred only around Britain’s own rearmament. While British rearmament will be the priority, the elephant in the room is clearly the struggle to supply munitions to Ukraine since 2022, and the strategic fright provided by the Trump Administration in revealing the fragility of the munitions bottleneck when over-relying on US defence manufacturing and willingness to supply. Ukraine, and Europe more broadly, will need munitions at scale, and Britain is clearly positioning itself to be a preferred munitions provider to European allies as a means of stimulating domestic economic growth.

This is surely no coincidence from Starmer’s Labour government, although simply one not recognised elsewhere in commentary thus far. One of the only hopes to alleviate the fiscal situation behind funding defence will be to build an arms export model as part of the ‘NATO First’ approach. If Britain can indeed scale up its munitions production in a timely fashion, then Starmer may have greatly increased Britain’s strategic value to Europe as a whole. Britain could well become the partner of choice in supplying munitions to Europe and NATO, while reverting back to a more maritime strategy of offshore balancing through naval strength.

2. Cyber and the digital targeting web

With regards to cyber warfare, the main announcement was the creation of a Cyber Electromagnetic (CyberEM) Command within the broader Strategic Command. The need for such a command is driven by a recognition that there ‘are pockets of excellence within Defence, but they risk being less than the sum of their parts’.[18] Yet the CyberEm Command is tasked not with directing execution itself –this is to remain with the secretive National Cyber Force (NCF)– but instead with ‘ensuring domain coherence’ across defence.[19] As Devanny notes, while establishing such coherence is eminently sensible, focusing only on areas that defence ‘owns’ within its purview, it leaves hanging in the balance the question of exactly ‘how best to use the NCF’.[20]

This has been a consistent challenge at the heart of cyber’s place in defence and broader national security, that this author has raised on previous occasions. In a previous article when the NCF was publicly avowed, I raised the concerns of a ‘conceptual black hole in British strategic thought’ if the place and role of the NCF was not clearly elaborated.[21] This was not resolved by the Integrated Review, and certainly not through the NCF’s own publication articulating the idea of ‘responsible democratic cyber power’.[22] Even though the SDR is defence-focused and we must acknowledge cyber as a wider challenge, Devanny is right, if understated, in saying that ‘It is, however, slightly disappointing that the SDR did not have more to say about it’.[23] While CyberEM is both well intentioned and certainly necessary, it alone does not provide sure answers to the central questions behind the place, operating concepts, doctrine and wider strategy behind how Britain will wield its cyber power in the years to come.

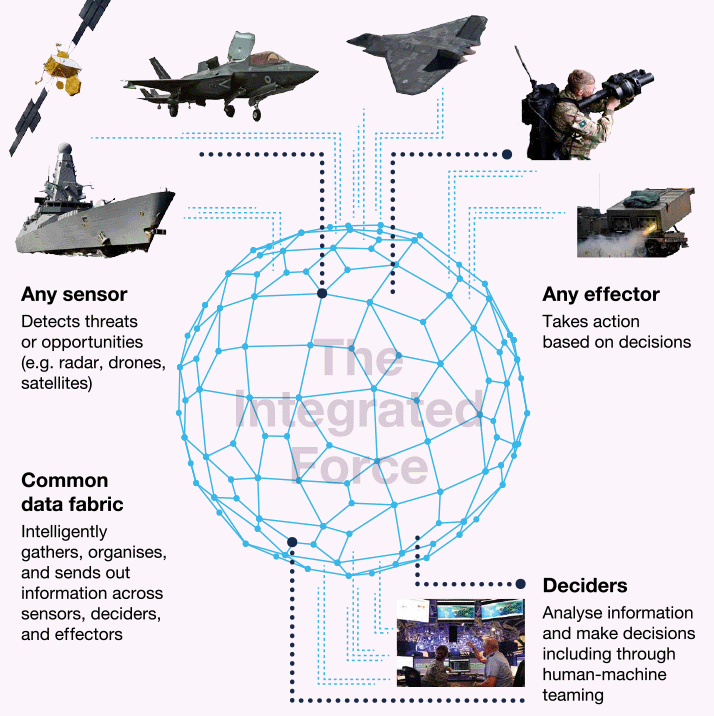

While the conceptual black hole remains at a strategic level, the SDR does provide a positive operational route forward, which is the concept of the ‘digital targeting web’ as illustrated below.

Figure 1. Digital targeting web

Central to a much-reduced British armed forces in structure and personnel, and with it the necessary desire for increased lethality in place of quantity of force, the digital targeting web concept is intended to deliver this effect to connect ‘sensors’, ‘deciders’ and ‘effectors’ to ‘create choice and speed in deciding how to degrade or destroy an identified target across domains and in a contested cyber and electromagnetic domain’.[24] This, far from being revolutionary, needs to be recognised for what it truly is at heart, a rediscovery of the Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) thesis that postulated the future vision of high technology driven military forces of the early post-Cold War period. There is a substantial literature on this subject, suffice to say for the needs of this analysis that one of its most famed proponents –US Admiral William A. Owens– postulated the ‘systems of systems’ approach as part of this modern RMA with technology at its heart that had three main components, ‘intelligence, command and control, and precision force’.[25] Later, Owens went further in his 2000 book in arguing that the US military ‘has failed to realise the true promise of the Revolution in Military Affairs’.[26] If the promise can be fulfilled, it has always been hoped the ‘fog of war’ can indeed be lifted, as served for the title of Owen’s book.[27]

With the concept of the digital targeting web, the RMA thesis is receiving a 2020s facelift. Any observer from the 1990s would immediately recognise the desired force structure and increased lethality effects that Britain now desires for its military. The difference today lies in the recognised centrality of cyber as the connective tissue underpinning the feasibility of the idea, something Owens did not accurately foresee in the 1990s. ‘Informed by AI and supported by a common synthetic environment, the targeting web epitomises how the Integrated Force must fight and adapt’.[28] In a sense, this is a Britain seeking to hedge its cyber bets, in having an NCF to perform strategic offensive cyber operations (the futurist view), and a military force structure utilising cyber connectivity to enhance the lethality of its conventional platforms (resurrecting the RMA).

Conclusions

To conclude, the SDR –as constrained as it is by the Labour’s government’s grapple with hard fiscal realities– maintains a true enough course to Britain’s historic strategic tradition while finding its footing for the realities of the future of warfare as being evidenced by Ukraine. This is to the benefit of European allies in Britain reaffirming its security focus on continental Europe once more through ‘NATO First’. Britain –if its ambitions can be delivered on time and according to a meagre budget growth– continues to inch its way forward to a modernised concept of war fighting, utilising conventional and digital means. If Britain gets it right, perhaps it can prove that the RMA was never meant to be a revolution at all, but instead a careful evolutionary tale for how major state actors can fuse the epitome of industrial age military might to the promise of digital technologies and cyber means.

[1] HMG (2025), The Strategic Defence Review 2025 – Making Britain Safer: Secure at Home, Strong Abroad, 2/VI/2025.

[2] Dr Joe Devanny (2025), ‘Cyber and the Strategic Defence Review: all pervasive but light on details’, 11/VI/2025.

[3] SDR (2025), p. 7 and ch. 7.3.

[4] Ibid, p. 49.

[5] Starmer in ibid, p. 2

[6] Jane Merritt & Molly Blackall (2025), ‘Defence wins on paper as Chancellor backs PM’s funding boost’, The I Paper, Thursday, 12/VI/2025, p. 10.

[7] Ben Riley-Smith, Martin Evans, Danielle Sheridan & Charles Hymas (2025), ‘Reeves hits police and defence to fund NHS’, The Daily Telegraph, Thursday, 12/VI/2025, p. 1.

[8] Ben Wallace (2025), ‘Rachel Reeves may have just killed NATO’, The Daily Telegraph, Thursday, 12/VI/2025, p. 16.

[9] HMG (2021), Global Britain in a Competitive Age: The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy..

[10] SDR (2025), p. 13, op. cit.

[11] SDR (2025), p. 15, op. cit.

[12] In the British case, always subject to debate between ‘navalists’ who prioritise naval strategy over ‘forward balancers’ who favoured troop deployments on the ground. Colin Dueck (2022), ‘Offshore balancing: the British analogy, 1688-1783’, p. 3..

[13] Andrew Lambert (2021), ‘Britain: a natural seapower’, 2/III/2021.

[14] SDR (2025), Ch. 7.1 & 7.2, op. cit.

[15] HMG (2025), Press release, 1/VI/2025..

[16] Starmer in SDR (2025), p. 2, op. cit.

[17] HMG (2025), op. cit.

[18] SDR (2025), p. 120, op. cit.

[19] Ibid, p. 21.

[20] Devanny (2025), op. cit.

[21] Danny Steed (2021), ‘The National Cyber Force: directions and implications for the UK’, 9/II/2021.

[22] National Cyber Force (UK), Responsible Cyber Power in Practice, 4/IV/2023.

[23] Devanny (2025), op. cit..

[24] Ibid., p. 29.

[25] Admiral William A. Owens (1996), The Emerging US System of Systems, p. 1..

[26] Admiral Bill Owens with Ed Offley (2000), Lifting the Fog of War, Farrar Straus & Giroux, p. 22.

[27] Ibid.

[28] SDR (2025), p. 29, op. cit.