Key messages

- Water is central to the EU’s climate resilience, serving as a critical link between mitigation and adaptation in the face of escalating climate-related risks. The interdependence between water and energy further underlines how crucial both are for the Union’s security and resilience.

- Southern Europe and the Mediterranean are climate hotspots experiencing intensified water-related climate risks: droughts, floods and changing rainfall patterns. They constitute potential pilot zones for scalable water resilience solutions to inform policies in climate-vulnerable areas and the design of water-related adaptation measures.

- The European Water Resilience Strategy (EWRS) provides the main comprehensive EU-wide framework to strengthen water resilience through three strategic objectives: to protect and restore Europe’s water cycle, to foster a water-smart economy and to ensure universal access to clean water and sanitation.

- The EU Council has endorsed this holistic approach, calling for integrated and cross-sectoral action to safeguard ecosystems, modernise infrastructure and strengthen preparedness for extreme water events, further strengthened by the Madrid high level ministerial meeting.

- Effective implementation of the EWRS depends on five enabling areas: governance, financing and infrastructure, digitalisation, research and innovation, and security and preparedness.

- The EWRS could provide a systemic blueprint that can be fully integrated into the forthcoming Integrated framework for European climate resilience and risk management and thus could also be aligned with the EU’s contribution to global adaptation efforts under the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA).

- Strengthening water resilience is not just key for risk management but also a strategic choice to enhance water security, which is essential for health, economic stability and competitiveness, while contributing to the restoration of the water cycle’s resilience to accelerate climate adaptation.

Analysis

Introduction

In December 2025 the EU hosted its first EU Water Resilience forum, which took further steps on the operationalisation of the European Water Resilience Strategy (EWRS) that was presented six months before, on 4 June. The EU Water Resilience Strategy places water at the heart of the EU’s efforts to strengthen climate resilience, offering a systemic response to the EU’s mounting water-related challenges. It is structured around three main goals: restoring and protecting the EU water cycle; building a water-smart economy; and ensuring clean and affordable water and sanitation for all.

On 25 October 2025 the Council of the EU adopted its conclusions on the EWRS, reflecting a unified call from Environment Ministers for a holistic and cross-sectoral approach to safeguard the EU’s water resources linked to the upcoming European Climate Resilience and Risk Management initiative. Also in October, the High-level Ministerial meeting on water, sanitation and climate, convened in Madrid by Sanitation and Water for All (SWA), drew renewed political attention to the links between water security, climate resilience and sustainable development. The discussions among ministers and experts, held under the theme ‘Breaking silos: uniting political leadership for integrating water, sanitation and climate action’ aimed to strengthen cooperation across these sectors and to enhance resilience to growing water-related risks.

These initiatives are framed in the light of increasing water risks due to water scarcity, droughts, floods and pollution. Water is coming to the fore as both a critical and strategic resource central to the resilience and stability of societies, economies and ecosystems. The water cycle –conceptualised as a set of continuous processes involving the movement and distribution of water through evaporation, condensation and precipitation– is undergoing substantial changes in what some authors have called the ‘water cycle for the Anthropocene’, a deeply altered water cycle. Indeed, a key element is variability, which means access to reliable and sufficient water can no longer be taken for granted in the context of climate change. The EWRS seeks to restore a ‘broken’ water cycle, strengthening the value and importance of a fully functioning and healthy water system. Ministers underline the need to incorporate climate change scenarios into long-term water planning and infrastructure development, consistent with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessments. Anticipating climate-related water risks requires access to reliable information, the development of skills and tools for decision making, and to engage actively in both prevention and preparedness, as stated in the EU Preparedness Union Strategy.

Managing climate risks is critical to improving water security as climate change alters both the availability and quality of water, as well as the frequency and intensity of water-related extreme-weather events. In this context, water is vital for both climate mitigation and adaptation. From cooling technologies in low-emission power plants, to support the carbon sequestration capacity of natural ecosystems, and the restoration of wetlands, to buffer against floods or to recharge aquifers, water plays a vital role in systemic resilience.

At the same time, water is inherently local, deeply political and often transboundary –over 60% of Europe’s rivers, for example, are shared across countries–. Water scarcity, if not managed, could lead to increasing tensions, both locally and internationally, as resources diminish and the timing and seasonality of water availability shifts. While the evidence and prospect of outright ‘water wars’ remains limited within the EU, there is growing evidence that conflicts over water can spill over and amplify into broader crises, hence the importance of water diplomacy. The 2024 UN World Water Development report, which focused on water and cooperation, underscored this point, stating that water is central to securing peace and prosperity.

Disruptions to the water cycle have direct and indirect implications across sectors. The economic value of water and freshwater ecosystems exceeds €11.95 trillion in Europe –around 2.5 times the GDP of Germany–. Water supports different sectors, including agriculture, industry and energy, and is also fundamental to health –eg, shortages in drinking and sanitation water, increased exposure to water, food and vector-borne diseases, and to mental distress–. The cascading implications of a disrupted water cycle highlight the need to strengthen water resilience, not only as an environmental concern but also as an element affecting economic and social stability. Water resilience, ie, the ability to withstand, recover from, and adapt to adverse conditions, such as crises, disasters or systemic disruptions, is therefore essential in limiting the escalating impacts of climate change.

To address the above concerns, the current European water legislation provides a solid basis to build water resilience. Key instruments include the Drinking Water Directive, the Industrial Emissions Directive , the Urban wastewater Directive, all of which have been recently updated, in addition to ongoing current water-planning cycles under theWater Framework Directive (WFD), the cornerstone of EU water legislation, and theFloods Directive. Together, these directives aim to ensure sustainable water management, safeguard water quality and enhance preparedness against extreme-weather events. The challenge lies in ensuring its effective implementation and cross-sectoral policy integration.

Historically, (eco)system resilience has been one of the important founding principles of the EU water policy and regulatory framework, an approach reinforced by increasing evidence of severe strain on water ecosystems. For example, the European Union Climate Risk Assessment (EUCRA), published in March 2024, identified water risks and ecosystems as the policy areas with the highest number of risks either in the categories of ‘urgent action needed’ or ‘more action needed’. Furthermore, the recently published Spanish climate risk assessment (ERICC) also identifies water as a structural node in the system, where the effects of climate on the water cycle –floods, extreme droughts and reduced water availability– are at the heart of the most critical interactions, acting as triggers for cascading impacts that affect other sectors such as energy, cities, agriculture and health.

At the international level, the EWRS can also contribute to a broader global momentum to scale up efforts on climate adaptation. A key development in this regard is the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), a collective commitment under the Paris Agreement to enhance adaptive capacity, strengthen resilience and reduce vulnerability to climate change. Negotiations on the GGA under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) concluded at COP30 in November with the adoption of 59 indicators, nine of which relate directly to water. These indicators are designed for long-term monitoring of adaptation progress. Aligning them with the EU’s domestic strategies –such as the EWRS– offers an opportunity to articulate a coherent, long-term European vision for global water resilience.

This paper seeks to highlight the window of opportunity that the EWRS can provide to reinforce important policy processes currently under way at both the European and international levels. On the one hand, to support Europe’s goal to meet its Net Zero commitments by 2050 and thus the implementation of Member States’ National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs); on the other hand, to develop the EU’s vision to be climate resilient by 2050 and its positioning in relation to water in the GGA.

The EWRS: a turning point for EU water management?

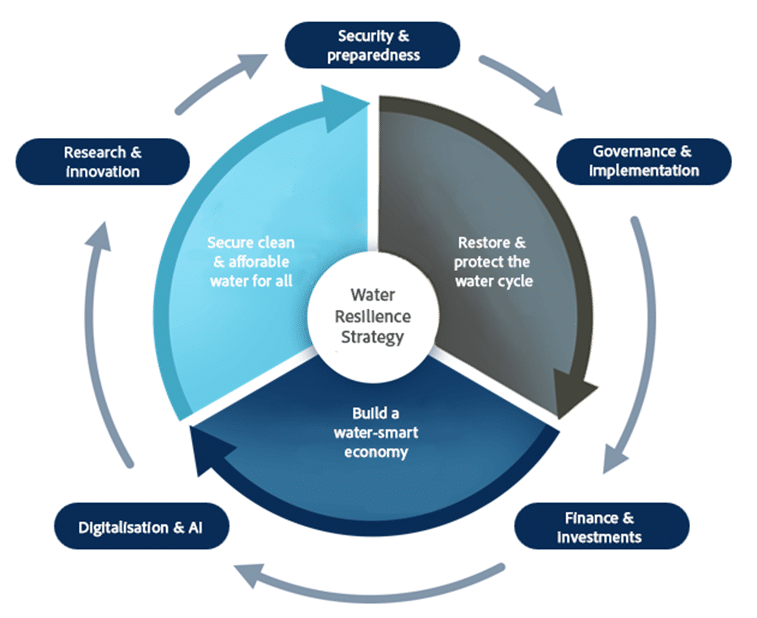

The EWRS signals a fundamental shift in how the EU approaches water management. It positions water not only as an environmental asset but also as a strategic resource for competitiveness, long-term security and climate resilience. For the first time at the EU level, water governance is framed alongside the energy and climate transitions. Figure 1 below depicts the objectives (inner circle) and areas (outer circle) on which the EWRS is focused.

Figure 1. European Water Resilience Strategy, its three objectives and five enabling areas

The EWRS includes a suite of time-bound, EU-led and Member State-supported actions across its three objectives. These actions target a broad range of challenges, from addressing pollution from pharmaceuticals, PFAS compounds and other emerging contaminants of concern, to promoting water re-use and improving efficiency guided by the ‘water efficiency first principle’. Figure 2 summarises the proposed actions and timelines from 2025 to 2028.

Figure 2. Key objectives and flagship actions of the European Water Resilience Strategy

| Key objectives | Flagship actions | Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| Restoring and protecting the water cycle | Establish implementation priorities for the Water Framework and Floods Directives via Structured Dialogues with Member States | 2025-26 |

| Revise the Marine Strategy Framework Directive | 2027 | |

| Develop water scarcity indicators and drought management technical guidance | 2026-27 | |

| Support addressing main sources of pollution: Public-private initiative for PFAS detection and remediationAssistance Toolbox for nutrient pollution reduction | 2027 2026-27 | |

| Building a water-smart economy that leaves no one behind, supports EU competitiveness and attracts investors | Develop ‘water efficiency first principle’, guidelines, and EEA report on untapped efficiency potential | 2025-26 |

| Support uptake of water reuse practices and review the Water Re-use Regulation | 2026-28 | |

| Public water supply: support leakage reduction, infrastructure modernisation and data assessment | 2025-28 | |

| Agriculture: maximise the use of Common Agricultural Policy Strategic Plans for water resilience via knowledge sharing, innovation networks (EU CAP network, EIP-AGRI), and improved farm advisory services; incentivise farmers to enhance environmental and climate performance, including better water management practices | 2025-26 | |

| Industry and Energy: pilot projects for water-efficient technologies; include water usage as a parameter in data centre sustainability ratings; develop water consumption minimum performance standards; public-private initiative for affordable dry cooling technologies | 2025-27 | |

| Securing clean and affordable water for all, empowering consumers and other users | Address water footprint in product requirements under ESPR and EU Ecolabel | 2025-27 |

| Promote public awareness and best practices regarding water pricing to support water efficiency and national water governance | 2026-27 | |

| Boost water resilience in buildings through the New European Bauhaus Facility and the Affordable Housing Initiative | 2026 |

Beyond its headline objectives, the EWRS sets out five enabling areas that are essential to turning strategic ambition into concrete outcomes. These cross-cutting areas include governance and enforcement, financing, infrastructure and investment mechanisms, digitalisation and AI, research and innovation, and security. Figure 3 summarises these areas and their respective actions, highlighting the support framework that underpins the strategy’s successful roll-out.

Figure 3. Enabling areas and flagship actions under the European Water Resilience Strategy

| Enabling areas | Flagship actions | Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| Governance and implementation to boost change | Strengthen enforcement and structured dialogues with Member States to accelerate EU water acquis implementation | 2025-26 |

| Promote best practice exchanges on ‘sponge landscapes’ (ie, landscapes where soils have the capacity to retain water and humidity) and transboundary water cooperation under the Cohesion for Transitions Community of Practice | 2025-27 | |

| Launch an environmental and spatial data viewer to support Member States in localising water-intensive businesses | 2027 | |

| Finance, investments and infrastructure to achieve a stable supply | Launch EIB Water Programme and Sustainable Water Advisory Facility to support project financing, with €15 billion planned for 2025-27 | 2025 |

| Support reorientation of Cohesion policy funds towards water resilience | 2025 | |

| Establish a Water Resilience Investment Accelerator | 2026-27 | |

| Launch a Green and Blue Corridors initiative for ecosystem and infrastructure restoration | 2027 | |

| Adopt a Roadmap for Nature Credits to scale up these markets | 2025 | |

| Digitalisation and Artificial Intelligence to accelerate and simplify sound water management | Develop and implement Destination Earth and EU Digital Twin of the Ocean applications for water resilience; make capabilities available to national and local administrations by 2030 | 2025-30 |

| Develop an EU-wide Action Plan on digitalisation in the water sector, including an initiative on smart metering for all | 2026 | |

| Launch a Copernicus Water Thematic Hub | 2026 | |

| Research and innovation (R&I), water industry and skills to strengthen competitiveness | Create a science-policy interface to disseminate results of EU-funded R&I projects through a one-stop shop platform | 2026 |

| Develop a Water Resilience R&I Strategy | 2026 | |

| Launch the Water Smart Industrial Alliance to stimulate competitiveness | 2026 | |

| Establish the European Water Academy led by the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the academy aims to address capacity needs in Europe’s water sector and to bridge research and real-world application of technologies by offering advanced training, supporting innovation, and fostering cooperation between public and private actors across Europe | 2026-27 | |

| Set up a Knowledge and Innovation Community (KIC) on Water, Marine and Maritime Sectors and Ecosystems under the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT) | 2026 | |

| Security and preparedness to boost collective resilience | Enhance resilience of onshore and offshore water infrastructure via the Critical Entities Resilience Directive | 2025 |

| Strengthen EU early warning and monitoring systems by upgrading the European Drought Observatory and the European Flood Awareness System | As from 2025 | |

| Adopt a European Climate Adaptation Plan | 2026 |

While the EWRS sets out a technically robust and strategically coherent roadmap, its impact will depend on overcoming persistent and structural challenges that have long undermined EU water policy. Moving from strategy to tangible outcomes requires more than political alignment at the EU level: it demands effective implementation, cross-sectoral policy integration, adequate financing, and targeted support to address regional capacity gaps and needs.

First, implementation gaps within the existing EU Water policy framework remain a critical barrier. As highlighted in successive assessments of the WFD, the failure to achieve its objectives is not due to shortcomings in the legislation itself, but primarily to weak implementation and enforcement. Over the past two decades, the ecological status of European water bodies has improved only marginally. Many Member States still struggle with inadequate enforcement, incomplete river basin management planning, and the failure to address diffuse pollution from agriculture, hydromorphological pressures and excessive water abstraction. Without decisive action to bridge these gaps, the EWRS risks adding a new layer of ambition to an already under-delivered regulatory agenda. At the recent first EU Water Resilience forum specific attention was given to the area of financing water resilience and where one of the key underpinning issues identified related to better water pricing.

Secondly, territorial and institutional inequalities across Member States further threaten the strategy’s cohesion and solidarity objectives. Differences in monitoring capacity, administrative strength and investment readiness may hinder the uptake of key tools promoted by the strategy, particularly digitalisation, smart metering and the expansion of water reuse. This divergence risks reinforcing a ‘two-speed Europe’ in water resilience, unless technical support and knowledge transfer are significantly scaled up.

Third, although the EWRS calls for a 10% improvement in water efficiency by 2030 and encourages Member States to set national targets (as France has done), it lacks binding commitments. Most of its objectives remain non-compulsory, with the implementation left to national discretion. This voluntary approach, combined with weak enforcement mechanisms, raises doubts about the strategy’s capacity to generate the scale and speed of change required, particularly in sectors like agriculture, where water use reform often faces strong political resistance. Additionally, environmental organisations have voiced concerns about how the strategy frames efficiency as an end in itself rather than a means to reduce overall pressure on water resources, and for failing to address the rebound effect, whereby efficiency gains are offset by higher overall consumption.

In this context, it is crucial to reduce water use in sectors with the highest levels of water abstraction and the greatest savings potential. Electricity production (36%), agriculture (29%), public water supply –covering drinking water, household usage and tourism– (19%), and manufacturing (14%) together represent 98% of total water abstraction in the EU. Yet the strategy does not introduce policy instruments to manage water use in those sectors, undermining its capacity to drive systemic transformation where it matters most.

Water resilience will also be critical for established sectors, like the urban water cycle, agriculture and industry, where the pursuit of climate neutrality goals may conflict with ecosystem protection. This is evident in the use of reservoirs for water and energy storage, or the expansion of new energy sources such as green hydrogen. Therefore, to increase the resilience of both new and existing energy infrastructure, it is important to incorporate hydrological forecasting and monitoring systems to manage climate extremes and build systemic resilience.

As regards finance, the Council of the EU reiterates the need for continued investment in resilient infrastructure, digital tools and early warning systems to mitigate the impacts of water extremes. While initiatives such as the proposed Water Resilience Investment Accelerator and the European Investment Bank’s new Water Programme, committing over €15 billion in financing for 2025-27, imply a significant degree of progress, they might still be insufficient to close the funding gap. According to the EWRS, a persistent annual investment shortfall of around €23 billion highlights the urgent need to further mobilise both public and private capital. Priority areas include infrastructure upgrades, digital water systems and leakage reduction, as national water losses currently range from 8% to 57%. In Spain, average losses are estimated at between 15% and 25%, with significant variations across municipalities.

This structural funding gap is further underscored by an analysis from Water Europe, which estimates that up to €255 billion will be needed by 2030 to comply with existing EU water legislation and enhance water efficiency across the continent. In this context, the European Commission has unveiled its proposal for the 2028-34 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), a nearly €2 trillion seven-year budget that allocates significant funding towards achieving the EU’s water resilience and broader environmental goals. Additionally, the EU has pledged to increase cohesion policy funding for water, to adopt a roadmap for nature credits and to create a Sustainable Water Advisory Facility. However, without a dedicated, long-term EU-level water financing mechanism, many flagship actions remain at risk of not being implemented.

Furthermore, the EU’s implementation of water pricing, cost recovery and the polluter-pays principle remains incomplete, despite these being critical enablers of sustainable and economically sound water management practices. The lack of a transparent and consistent application of these key economic mechanisms and principles deprives Member States of vital revenue streams to fund water-related measures and shifts hidden environmental and resource costs onto society. This is particularly relevant in the case of persistent pollutants such as PFAS (per-and poly fluoroalkyl substances), whose clean-up costs are estimated to amount to €100 billion annually across the EU, highlighting the pressing need to enforce the polluter-pays principle more effectively or, even more, the preventing of pollution as the most effective measure (source reduction) based on the precautionary principle.

A more explicit commitment to transparent, equitable and progressive pricing, for urban, industrial and agricultural abstractions, could align incentives, promote efficiency and reduce unsustainable use, while supporting the long-term financial sustainability of water systems. At the same time, appropriate social safeguards must be in place to ensure that access to essential water services remains affordable for vulnerable groups.

In addition, the effectiveness of such reforms ultimately depends on their social acceptability. Survey evidence for Spain indicates that around 49% of households would be willing to pay more on their water bill to secure sufficient quantity and quality of water in their homes. By contrast, while there is a considerable body of research on agricultural water use, most existing studies are highly sector-specific and focus on farmers’ willingness to pay for improvements in irrigation services or supply reliability. For industrial users, the available evidence is even more limited, with relatively few studies examining how they might respond to higher abstraction or pollution charges.

Policy fragmentation also remains a major obstacle to effective water resilience. Therefore, stronger conditionality and mainstreaming mechanisms are important. Thus, policy coherence will help to strengthen water objectives, through, for instance, digitalisation and smart irrigation systems or energy projects that do not take into consideration local water stress, shifting to cooling systems and fuels that are less water-demanding.

Lastly, the monitoring and governance architecture of the EWRS must be strengthened. Initiatives such as the Resilience Dashboards, the Copernicus Water Thematic Hub and the European Water Academy offer valuable instruments –but their success will depend on clearly defined indicators, transparent data sharing and meaningful integration into national planning systems–. Resilience must be supported by measurable progress metrics to ensure course correction, public accountability and long-term impact. Indicators are more than statistical outputs, they are strategic levers of change, directing political attention, flagging implementation gaps and helping transform policy ambition into concrete outcomes based on well-defined targets.

The EWRS constitutes a turning point in EU water governance because it embeds water within broader economic, climate and security agendas. Its effectiveness, however, will ultimately hinge on the EU’s capacity to overcome legacy implementation gaps, secure sustained investment, actively engage stakeholders (including citizens) and translate strategic objectives into concrete action across diverse regional contexts.

Strategic implications of the EWRS in the context of EU and global climate policy

The launch of the EWRS reflects a broader evolution in EU water governance, where water is recognised not only as a resource under pressure but also as a cross-cutting, strategic vector for climate resilience, strategic autonomy, sustainable development, welfare, competitiveness, health and security. By framing water resilience as a systemic enabler of both climate adaptation and mitigation, the EWRS could mark a significant shift from sectoral water management towards integrated resilience planning across the EU.

As indicated in the European State of the Climate 2024, Europe is the fastest-warming continent globally. The European Climate Risk Assessment (EUCRA), mentioned earlier, confirms the urgency to keep Europe within safe temperature thresholds, identifying water as one of the sectors exposed to a high concentration of risks requiring urgent additional action. These challenges are especially acute in Southern Europe, which was identified as a climate hotspot, as also shown in the Spanish Climate Risk Assessment (ERICC), with substantial declines in overall rainfall and more severe droughts, as well as more extreme flood events in recent years, accentuated by a warming Mediterranean Sea. As recently explained by Francisco Espejo, Research Director at the Spanish Insurance Compensation Consortium (CCS) in an interview with Forbes, ‘[t]he Mediterranean Sea is reaching sea surface temperature of nearly or above 30°C in the summer, and that’s a weather bomb. For each degree that the temperature of the air rises, the capacity of the atmosphere to hold water vapor rises by 7%’.

This regional urgency should be mirrored in national climate planning. In May 2025 the EU published its evaluation of the 23 updated National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) submitted by Member States. All NECPs analysed by the EU –except Luxembourg’s– looked at adaptation and 16 NECPs referred to water directly or indirectly. Among these, the Commission identified eight countries (Croatia, Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal and Spain) –all located in the Mediterranean hotspot already identified in the EUCRA– as requiring substantial efforts to strengthen water-related adaptation. Moreover, these NECPs highlight the importance of managing the water-energy nexus in the Mediterranean context, where both mitigation and adaptation intersect, eg, through the management of risks like water scarcity in the energy system (in hydropower and green hydrogen production) and the need to enhance systemic water resilience. This underscores a window of opportunity for the EWRS to lay the ground for integrating water resilience into the broader climate and energy planning, in alignment with the recent EU Preparedness Union Strategy.

The newly launched Pact for the Mediterranean explicitly recognises the region’s acute climate and water pressures, yet its adaptation pillar –including water management– remains insufficiently developed, with limited clarity on governance, long-term planning and financing. These gaps constrain its ability to support or reinforce EU efforts such as the EWRS and therefore should be addressed and included in the upcoming Action Plan.

Indeed, the European Network of Transmission System Operators, representing 39 electricity transmission system operators (TSOs) from 35 countries (ENTSO-E), has turned its attention to the role of water in energy transition planning, recognising both the risks and opportunities that water offers in the broader context of enhanced climate change coupled with increasingly ambitious decarbonisation strategies. In the same vein, the accompanying communication to the EWRS’s ‘water efficiency first’ clearly states that ‘[t]he interdependence between water and energy resources is a critical factor in ensuring the security and resilience of the Union’s water and energy systems’.

Looking ahead, the success of the EWRS will depend on its alignment with broader EU policy instruments, especially the forthcoming European climate resilience and risk management framework, due at the end of 2026, and which is open for public consultation until February. Announced in the Political Guidelines for the 2024-29 European Commission by Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, it aims ‘to support Member States notably on preparedness and planning and ensure regular science-based risk assessments’ and must go hand in hand with strengthening Europe’s water security. This will build on the already running EU Mission to Restore Oceans and Waters and the EU Mission Adaptation, which directly engage more than 300 regional and local authorities across the EU.

At the international level, the EWRS could be aligned with the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), established under Article 7 of the Paris Agreement. The GGA seeks to enhance adaptive capacity, strengthen resilience and reduce vulnerability to climate change. It aims to contribute to sustainable development while ensuring an adequate adaptation response in the context of the temperature goal of 1.5ºC. In 2021 a two-year work programme was launched to explore how to conceptualise and measure adaptation progress. In 2023 the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience was adopted and technical work carried out under the UAE-Belém work programme (2024-25). This process, concluded at COP30, established 11 global targets to be achieved by 2030, seven being targets on specific themes on climate action: health; biodiversity; food; infrastructure; poverty; heritage; and water. And the other four targets are transversal to the adaptation cycle: climate risk and vulnerability assessments; planning; implementation and monitoring; and evaluation and learning.

Over 9,000 adaptation indicators were originally proposed for the GGA by Parties, UN agencies and other stakeholders –650 of which referred to water–. The latter covered metrics on reducing climate-induced water scarcity, enhancing climate resilience to water-related hazards, ensuring a climate resilient water supply and sanitation as well as securing access to safe and potable water. The EU alone submitted more than 1,000 indicators spanning all the thematic and cross-cutting areas, with 40 indicators directly related to water. Of these, 10 refer to the risks posed by drought and water scarcity, which is unsurprising considering that droughts affect approximately 4% of the Union’s territory every year and caused an estimated €50 billion of economic losses in 2022 alone, with the largest losses recorded in Italy, Spain and France. The EU also submitted around five indicators that address flood risks and two related to water re-use and desalination. In the future, anchoring EU water policy within sectoral adaptation pathways set within the globally agreed indicator framework can strengthen multilevel governance, with vertical coordination between the EU, Member States, regions and catchments all the way to cities and small localities, while improving horizontal integration across sectors and actors. This provides an important base to inform the implementation of the EWRS itself and creates a more coherent foundation for adaptation planning ahead of the 2026 integrated framework for European climate resilience and risk management.

The curated GGA list of 100 indicators, prepared by technical experts, included 10 on water and an accompanying expert technical report, were published in September. As expected, at COP30 one of the most anticipated outcomes was the adoption of the Belém Adaptation Indicators. The indicator list was reduced from the 100 proposed to the 59 selected indicators. On water, nine of the 10 recommended indicators were retained in the final list, ie, nearly a quarter of the 38 indicators adopted for thematic areas –an acknowledgement of water’s central role in climate resilience–. These decisions on selected water indicators open an opportunity for Europe, for the Mediterranean and for Spain to further define water resilience and its measurement in order to track the effectiveness and fairness of adaptation measures.

Conclusions

Water is a finite resource that is increasingly under pressure. Climate change is already reshaping Europe’s societies, economies and ecosystems. In this context, the adoption of the EU Water Resilience Strategy is an opportunity to leverage both the EU’s adaptation and mitigation strategies. By positioning water at the intersection of environmental protection, economic competitiveness, health and security, it moves beyond sectoral water management towards a more integrated, systemic approach to risk management and resilience planning. To achieve the EWRS’ objectives, the Commission has proposed actions in five key areas: implementation and governance; investments; digitalisation; R&I; and security and preparedness. The EWRS does not propose new legislation but rather focuses on effectively implementing existing rules and meeting policy objectives already set.

In this respect, the strategy’s transformative potential will depend on its capacity to overcome longstanding barriers that have constrained the implementation of the EU’s water policy. These include uneven enforcement across EU Member States, disparities in technical and administrative capacity, a lack of meeting binding commitments, and significant gaps in investment and finance. Without concerted efforts to close these gaps, the EWRS risks being aspirational rather than operational. With water risks becoming more present to current and future EU competitiveness, it is also an opportunity for Europe to transition from a fragmented water policy landscape to one that is anticipatory, integrated and resilient in the face of increasingly complex and cascading climate risks. Accelerating EU leadership in the water sector –an often forgotten factor of production– can provide a new opportunity for innovation and resilience. Water can be a key limiting factor for established or new economic sectors, therefore investing in water resilience is securing economic resilience, particularly in rapidly changing and challenging geopolitical times.

The EU Climate Risk Assessment (EUCRA) underscores the EU’s exposure to water-related risks requiring urgent and comprehensive action, a concern echoed in the recent review of 23 updated NECPs, where all but one addressed adaptation, and 16 mentioned water resilience, especially Mediterranean countries. These NECPs also stress the importance of managing the water-energy nexus in the Mediterranean context, presenting a clear opportunity for the EWRS to embed water resilience within broader climate and energy planning, in alignment with the EU Preparedness Strategy. Southern Europe –and Spain as evidenced in its recently published climate risk assessment– is a recognised climate hotspot, which illustrates both the urgency and opportunity for action on strengthening EU and member-state water resilience.

The strategy can also serve to reinforce the EU’s credibility and leadership within the UNFCCC during very turbulent times for multilateral climate governance, particularly in the context of the Global Goal on Adaptation, where water is a thematic target. From a list of 100 indicators proposed by technical experts, 59 were ultimately retained, among them nine directly related to water. These indicators can provide an important base to improve vertical and horizontal policy alignment, as well as to inform the implementation of the EWRS at the EU and member-state levels. The future integrated framework for European climate resilience and risk management –due at the end of 2026– offers the opportunity to get ahead of the game by operationalising water resilience and adaptation goals to accelerating water risks in order to be better prepared and more competitive.