Theme: With North Korea unwilling to halt WMD proliferation yet in the middle of an opening up process, the EU’s policy has to carefully balance non-proliferation activities with economic engagement.

Summary: There is no indication that North Korea is going to stop WMD proliferation any time soon, at least without substantial inducements. Meanwhile, the Kim Jong Un government has initiated a process of economic opening up and tentative diplomatic engagement. These two realities call for the EU to focus on two areas on which it has the potential to have considerable impact – WMD non-proliferation activities and economic reform support. The EU’s approach should include both carrots and sticks. Mixing proactive and punitive measures would not undermine Brussels’ normative agenda or support for peace and security in the Korean Peninsula. On the contrary, the EU could be perceived in East Asia as an independent and engaged actor with strong knowledge of regional dynamics and willing to engage when necessary.

Analysis: The EU is facing a conundrum. North Korea has shown scant willingness to halt its nuclear programme and cease proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), as demanded by the United Nations (UN) and many in the international community. The EU is among those implementing sanctions and other measures to force the Kim Jong Un government to stop both. On the other hand, Pyongyang has accelerated implementation of economic reforms over the past few years. Presumably, Brussels would like to be at the forefront of efforts to support these reforms through economic engagement.

This dilemma between pressure and support is difficult to solve. Failure to apply sufficient pressure while openly backing economic change would signal that Brussels is willing to sometimes look the other way when dealing with regimes defying the international community. Also, the US and other partners would probably be critical of this approach. Meanwhile, too much pressure with economic engagement absent would reduce any leverage the EU might have in its relations with North Korea. Furthermore, this approach would probably discourage those seeking reform within the North Korean government.

Brussels, therefore, needs to apply a two-pronged strategy to deal with Pyongyang. This strategy ought to marry sufficient pressure to show North Korea that the EU will not tolerate its defiance of the international community, together – and above all – with productive engagement to encourage an honest dialogue as well as further economic reform and opening up. Can the EU strike the right balance between pressure and engagement to help to halt North Korea’s nuclear and proliferation programmes while simultaneously encouraging economic change?

The EU’s North Korea policy

Brussels’ policy towards Pyongyang is based on four pillars: peace and security in the Korean Peninsula, non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, human rights, and aid and cooperation. Nevertheless, the EU concedes that it mainly plays a supportive role with regards to the first pillar. Once the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO) effectively became redundant in late 2002 and the Six-Party Talks were set up in 2003, Brussels lost relevance in shaping inter-Korean security. As a result, non-proliferation, human rights, and economic support are the main aspects of the EU’s North Korea policy today.

Far from lumping together these three issues, however, the EU has become savvier in its approach towards North Korea. In common with its policy towards other authoritarian countries in East Asia (for example, China, Myanmar and Vietnam), Brussels prioritizes those areas in which it has the potential to have a real impact and which respond to the realities of regional geopolitics. As a result, the EU is concentrating heavily on halting North Korea’s WMD proliferation as well as on the promotion of economic reform.

This is not to say that EU officials consider the human rights situation in North Korea to be secondary. Brussels still co-sponsors UN General Assembly resolutions condemning Pyongyang’s human rights record, and the European Parliament has adopted several resolutions in this respect. But the reality is that open criticism of human rights problems does not work well in East Asia. It can even be detrimental to the EU’s policy towards the region, as shown recently when Myanmar’s opening up resulted in a quick re-assessment of Brussels’ priorities in a bid to catch up with other countries looking at other ways to encourage reform – including the US.

Furthermore, economic engagement has the potential to improve the human rights of ordinary North Koreans in a way that condemnations and sanctions do not. As Professor Hafner-Burton has forcefully argued, there is solid evidence that trade is effective at improving human rights standards. In the case of China, for example, economic engagement has been very useful in this regard. Therefore, it is logical for the EU to try this route – while prioritizing halting proliferation of WMD, a real threat to Europe’s security.

Stopping bombs: still the number one priority

The Kim Jong Un regime continues developing its nuclear programme for providing the regime with the security it craves. As Muammar Gaddafi found out in 2011, signing an agreement with Western powers to exchange WMD for better relations does not guarantee that these same powers will not turn against you at some point. It is not an exaggeration to believe that North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) support for the Libyan opposition during the country’s civil war makes the Kim Jong Un regime wary of suffering a similar fate. Indeed, North Korea already became reluctant to give up its nuclear programme as soon as it conducted its first-ever nuclear test, in October 2006. This reluctance has only become more apparent following Gaddafi’s death.

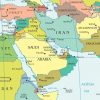

In the meantime, there is ample evidence that Pyongyang has been engaging in proliferation of WMD and nuclear technology for at least two decades. Both the Kim Jong Il and Kim Jong Un governments probably consider this activity as a means to secure hard cash – something necessary for a country that attracts very little foreign investment. Proliferation has the added advantage of enhancing independence from China. Contrary to popular belief, Beijing is not an uncritical and entirely reliable supporter of its Eastern neighbour. Weaker Sino-North Korean links started in 1992, when China and South Korea normalised diplomatic relations. With a willing customer base in the Greater Middle East, Pyongyang is unlikely to stop selling its ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons know-how to those willing to pay for them any time soon.

Halting North Korea’s nuclear programme and proliferation activities still remains the EU’s number one priority. To begin with, proliferation is a potential threat to the EU. Not only is the Greater Middle East part of its near abroad, but several member states have a military presence in the region. There is also a risk of weapons falling in the hands of terrorist groups seeking to strike inside the EU.

In addition, many consider the EU to be a normative power. Therefore, proliferation of WMD and nuclear technology is a breach of international norms to which Brussels cannot be oblivious to. Thus, even leaving aside the security risks inherent to arms circulating very close to its borders, the EU has an incentive to fight against proliferation to project a normative power image. Doing so enhances its credibility as an actor willing to share its burden as a responsible member of the international community.

Considering the above, it is no surprise that the EU has been a keen supporter of multilateral sanctions on North Korea. EU member states – particularly the UK – have been among the driving forces behind United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolutions imposing sanctions on Pyongyang following each of its nuclear tests. Brussels has even gone beyond implementation of these sanctions and adopted some of its own. For example, the Council announced stringent trade bans and financial restrictions following North Korea’s February 2013 nuclear test. Tellingly, these measures were announced less than a week after the test, suggesting that there is a consensus among EU member states that sanctions are key in deterring the Kim Jong Un government from strengthening its nuclear programme. In fact, High Representative for Foreign Affairs, Catherine Ashton, expressed South Korean Foreign Minister, Yun Byung-se, the EU’s willingness to impose more sanctions on North Korea, if necessary, as recently as May 5th.

Even more forcefully, EU member state military forces integrated in the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) have participated in the interdiction of North Korean cargo ships transporting WMD and related materials. Launched by the George W. Bush administration in May 2003, the PSI has been successful in halting several North Korean shipments over the years – Pyongyang proliferation activities being one of the main targets of the initiative. All EU member states and the EU itself participate in the PSI. Despite the secrecy surrounding PSI-related activities it is known that the navies of France, Germany, Spain and the UK have been actively involved in interdiction efforts.

Nevertheless, Brussels’ nuclear programme development and WMD proliferation-related strategy are more comprehensive than sanctions and interdiction activities would suggest. The EU seeks to maintain an annual political dialogue with North Korea in which proliferation features prominently, as well as regular inter-parliamentary meetings covering a range of issues. Given the limited number of contacts between North Korean and Western officials, these and other forms of engagement provide rare opportunities to address nuclear and proliferation concerns to North Korean officials directly. Brussels also remains supportive of the Six-Party Talks, the only international forum which Pyongyang has at least taken seriously in the last decade. Interviews by the author with several American, Chinese, Japanese and South Korean participants in the Six-Party Talks process confirm that the Kim Jong Il government did engage in an honest dialogue, at least during the 2005-07 period, when three joint statements were released.

Evidently, actions taken hitherto by the EU and others did not prevent North Korea from developing its nuclear programme. Meanwhile, the record on halting proliferation is unclear, given the lack of public information. However, the July 2013 interdiction of a North Korean ship carrying suspected missile parts by Panama shows that proliferation has not ceased. Therefore, it would be necessary for the EU to rethink its approach to Pyongyang’s nuclear programme and proliferation activities.

Any rethink should start with the recognition that sanctions and the PSI have not worked. They should be used to complement dialogue rather than as the policy of choice. The PSI and sanctions have been in place since 2003 and 2006, respectively. Yet, they have failed to stop Pyongyang from becoming a nuclear power and from continuing with its proliferation activities. Even though these measures signal the EU’s displeasure with North Korea’s behaviour, their ineffectiveness hitherto make both of them costly and detrimental to improving relations with North Korea. Thus, pressure should not be the main policy for Brussels to try to halt Pyongyang’s programmes.

The EU should instead decidedly support a real and honest dialogue with North Korea in which each party is able to express its views freely. As numerous negotiators with the Asian country have reported over the years, building sufficient trust for North Korean delegations to move beyond official rhetoric and engage in a real dialogue with their counterparts takes time. The Six-Party Talks are an example of a dialogue that achieved this level of trust. There is no reason to think that Brussels and Pyongyang cannot hold more regular meetings, in which inbuilt familiarity with each other – as well as consideration of North Korea’s security concerns – would lead to an open discussion about nuclear and proliferation activities. As the multilateral talks with Iran or indeed the Six-Party Talks demonstrate, reaching this degree of familiarity requires time, patience and mutual understanding. But maintaining an open communication channel is necessary for real dialogue to take place. Such a dialogue would have the added advantage of enhancing the effectiveness of pressure, since North Korea could not argue that the EU is unwilling to engage.

Encouraging shops: the real path towards change

Supporting North Korea’s economic reforms should be the second vortex of the EU’s approach to relations with Pyongyang. There is a debate among North Korea watchers regarding the extent to which the country is willing to push for genuine economic reforms. Existing evidence, however, strongly suggests that the Kim Jong Un government wants to implement the necessary changes to boost trade, attract investment, and kick-start economic growth. Located in the middle of four of the fifteen largest economies in the world, North Korea is uniquely placed to benefit from its location in one of the most economically dynamic regions in the world.

In fact, domestic economic reforms are not new to North Korea. In July 2002, meaningful reforms were first introduced. The government modified official prices to bring them closer to black market levels, increased wages and implemented a merit-based wage system, adjusted the won’s exchange rate to real levels, and increased managerial freedom for production units. Many other reforms have followed over the years. These include the legalisation of rural and urban markets, the creation of special economic zones, the launch of government markets, a loosening of collectivised farming structures, the updating if foreign investment laws, and the issuance of government bonds, among others. Certainly, many more reforms are needed. However, those implemented so far indicate that North Korea has left behind the days when the government oversaw all economic activity.

The marketization of the North Korean economy seems to have accelerated since Kim Jong Un took power. Most tellingly, in 2013 his government announced the opening of 14 special economic zones in different parts of the country. In addition, reports indicate that there has been a reorganisation of farm production units reminiscent of those introduced by China and Vietnam in the past. Reforms have also been introduced in the industrial base and the education system to move the country into the knowledge-based economy. Foreign residents in the capital Pyongyang say that signs of affluence are becoming more apparent by the day – including shops selling a wider variety of goods. Meanwhile, North Korean refugees from the rest of the country note that for years markets rather than state-owned companies have been the main drivers of the country’s economy outside of the capital. Since the North Korean government is unable to provide for its own population and wants to reduce economic reliance on China, it is logical to continue to implement real reforms.

An opening up process supports domestic economic reform efforts. The Kim Jong Un government has been openly courting foreign investment. For example, in October 2013 Pyongyang opened an embassy in Madrid, in a move apparently intended not only to tap into the Spanish-speaking market but also to cooperate with the World Tourism Organisation, headquartered in the capital of Spain. Business delegations from countries such as Mongolia, Russia, Thailand and several EU member states – including France, Germany and Italy – have visited North Korea in recent years. Concurrently, North Korea has dispatched delegations to several countries in Asia and Europe. It seems that the Kim Jong Un government is seeking to reduce its dependence on Chinese and South Korean investment. The former even accounted for up to 94 per cent of North Korea’s inward foreign direct investment as recently as 2008 (once South Korean investment is excluded). With regards to investment from its Southern neighbour, it is mostly channelled through the Kaesong Industrial Complex, where well over 100 South Korean companies have operations. The complex opened in 2002 and has only been closed twice since, in spite of recurring tensions between both Koreas that have affected all other types of bilateral cooperation. This shows the importance of the complex for the North Korean economy.

Ultimately, economic reform and opening up are the most promising avenues for real change and sustained growth. Reforms first introduced by China in the late 1970s and by Vietnam in the mid-1980s have been the main forces behind the significant improvement in the livelihoods of the Chinese and Vietnamese populations in the decades since. Both introduced reforms rather unexpectedly and have for the most part stuck to them. More recently, Myanmar has launched a process of economic reform that surprised most observers. Given that North Korea has already been implementing market-friendly measures for over ten years, there is no reason to think that the government is not willing to follow in the footsteps of other Asian countries.

The EU, to its credit, has been supportive of North Korea’s attempts at implementing long-lasting economic reforms. Aid is one of the pillars underpinning this support. Even though not directly related to the reforms themselves, aid provided by the European Commission and EU member states has served to improve the lives of ordinary North Korean citizens. This has allowed them to participate in market activities. The EU partakes in multilateral initiatives in areas such as medical, water and sanitation assistance, agricultural support, natural disaster resilience, and food security. All of these are essential in a country in which undernourishment and poor living conditions still affect hundreds of thousands of people, according to the World Food Programme and the Red Cross. Without aid from the EU and other countries – most notably China and South Korea – many North Korean regions would not have been able to move beyond being subsistence economies.

In addition and as stated above, there is solid evidence that economic engagement is beneficial for human rights – another essential component of the EU’s North Korea strategy. As an example, the EU and China maintain a human rights dialogue since 1995 which was only made possible after Brussels decided to mix carrots together with sticks in its relationship with Beijing. More recently, the EU and Myanmar held their first human rights dialogue in May of this year. Myanmar only agreed to this dialogue after the EU established a process of economic support to its reforms. It is very unlikely that North Korea will agree to discuss human rights with the EU unless sustained economic engagement takes place as well.

The second pillar of Brussels’ work to support economic change in North Korea is training and education. Dozens of North Korean economic officials have received economic policy-making and business training in countries such as France, the Netherlands or the UK. In addition, several Central and Eastern European countries – most interestingly, Poland – maintain good relations with North Korea dating back to the decades in which all of them were part of the Soviet bloc. Concurrently, institutions such as the British Council and the Goethe-Institut provide valuable language and cultural training to North Koreans from their Pyongyang offices.

Notwithstanding the above, the EU could more actively support the reform process in North Korea. In the area of training and education, the EU has two advantages that most countries cannot combine – Brussels is perceived as an honest broker and many of its member states have successfully transitioned from a command to a free market economy. In spite of these advantages, it is noticeable that the Pyongyang Business School is a Swiss initiative or that cooperation projects by European universities are led by groups of private citizens with little institutional support from Brussels. Truth to be told, North Korea is not the most reliable of partners. But it should not be forgotten that the then-European Economic Community (EEC) played a crucial role in training and educating Chinese officials following its reform process. More recently, the EU has been very quick in supporting Myanmar’s reform process. Given its economic strength and knowledge about supporting transition economies, the EU could implement North Korea-related programmes, fund regular exchanges, and support initiatives by European civil society organisations.

In addition, the EU could support European businesses willing to invest in North Korea. Direct economic support might be politically – and even legally – unfeasible. Nevertheless, initiatives such as executive training programmes in Japan and South Korea, the EU-China managers exchange and training programme, and trade capacity enhancing-related programmes with a range of East Asian countries are – or were, in the case of the EU-China programme – partly funded by the EU. The institutional structure and the funds for this type of initiatives already exist. Therefore, it should not be complicated to add North Korea to the group of countries covered by them. Given that its market economy is still in its infancy and the lack of support from relevant international institutions or other countries, North Korean officials and business people would arguably benefit more from these programmes than many of their East Asian peers.

Prospects for EU-North Korea relations

North Korea’s talks with the US will eventually resume, regardless of the format. In fact, relations have never completely broken down. Nonetheless, it is highly unlikely that Pyongyang will give up its nuclear programme any time soon. Thus, the EU has to be ready to more openly engage with a nuclear North Korea. Establishing a well-functioning and regular dialogue would allow Brussels to build trust with the Kim Jong Un government. This would help to underpin the EU’s concern about the human rights situation in North Korea as well, since engagement with other East Asian countries has proved to be useful in this respect. A dialogue would also serve the EU to have first-hand information on developments in North Korea, which has not always been the case in the past.

In the interim, Pyongyang will continue its reform and opening up process. This process has been ongoing for more than ten years, North Korea is seeking to diversify its investment sources, and a variety of actors are seeking to help the Asian country with its economic development. Brussels cannot afford to be the last one to arrive to the party, as seems to have been the case with Myanmar’s reform process. European companies would stand to benefit from a growing middle class in North Korea, as well as from the infrastructure development contracts that the government has already been adjudicating over the past few years. Almost all of these contracts have gone to Chinese and Russian companies. It is no secret that the Kim Jong UnIl government is trying to woo companies from other places as well – European countries included.

The EU’s North Korea policy is part of its broader Asia strategy. This is a continent to which both Brussels and individual member states have been paying more attention since the turn of the century. Engaging in a genuine dialogue about North Korea’s nuclear and proliferation activities while supporting its reform process would enhance the profile of the EU in Asia as an independent actor willing to take bold decisions. Furthermore, the EU would be projecting an image as a genuine global power rather than as an important economic partner only. Numerous studies show that Asian elites and general public have a positive view of the EU. However, these same studies indicate that Brussels is not perceived as a credible actor in the region. A clearer and less confrontational stance on North Korea could help to change that.

Is the EU ready to take such a stance? It is not easy, since a new approach would require dealing with North Korea as it is, not as Brussels – and many others – would like it to be. But the EU and its member states have in the past actively engaged with countries with which it would have seem impossible only a few years earlier. Equipped with a Common Foreign and Security Policy, a High Representative, a European External Action Service, and a growing interest in the Asian continent, it is certainly possible for the EU to marry limited pressure and greater engagement in a way that it serves North Korea’s and its own interests.

Ramon Pacheco Pardo

Lecturer at the Department of European & International Studies, King’s College London