Theme

Turkey’s growing military presence in Libya may prompt policymakers in Rome to shift away from Ankara and towards a deeper partnership with France in order to protect Italy’s extensive energy and economic interests in Libya itself and the rest of the southern and eastern Mediterranean basin. Such a Franco-Italian partnership, also taking in Egypt, would constitute a Mediterranean-wide realignment in the new ‘Great Game’ for the region’s energy and commercial connectivity. With Libya and its central Maghreb neighbours Algeria and Tunisia forming the main arena of this emerging geopolitical contest, Spain needs to recalibrate its regional policies to secure its economic and strategic interests in Libya and the wider Mediterranean region.

Summary

Turkey, Egypt, France, and Italy –the Mediterranean basin’s four largest countries– are engaged in a new ‘Great Game’ for the region’s energy resources and commercial transport routes. The geopolitical fault line between the four has featured a deepening partnership between France and Egypt to oppose Turkey while Italy, compartmentalising its eastern Mediterranean energy interests, has had a more distant alignment with Turkey based on a confluence of interests in Libya and the central Maghreb states of Algeria and Tunisia. Turkey’s 2020 intervention in the Libyan civil war, however, has altered Italy’s strategic calculus.

Although the intervention preserved the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA), in whose western Libyan territory Italy’s considerable energy assets are concentrated, Turkey’s outsized military presence has rendered Italy’s vital economic interests vulnerable to Ankara’s dictates. Italy had already moved closer to France in the eastern Mediterranean in 2018 to mitigate the risk to its energy interests in Cyprus from Turkish interference. As Turkey starts to leverage its status as Tripoli’s security guarantor to obtain contracts in Libya’s energy sector and infrastructure development, Italy seems to be on the verge of a tipping point where it may shift away from Turkey towards a Mediterranean-wide strategic partnership with France and Egypt. Spain faces the urgent task of carefully recalibrating its foreign policy in light of these developments to preserve its economic and security interests in Libya and the Mediterranean region as a whole.

Analysis1

The Mediterranean’s new geopolitical ‘Great Game’

The four largest countries in the Mediterranean basin –Egypt, Turkey, France and Italy– collectively comprise over half the region’s population. The scramble of these four to dominate the Mediterranean’s nexus of trade routes and energy transit routes that connect Europe, Africa and the Middle East is redefining the strategic architecture of the entire Mediterranean region. With the four most powerful militaries in the Mediterranean basin, the new ‘Great Game’ for Mediterranean energy and commercial connectivity features a hard power dimension manifested with each of these four powers’ involvement in the Libyan civil war.

France has engaged in covert cooperation with Egypt in support of General Khalifa Haftar’s forces in eastern Libya against the western Libyan Government of National Accord (GNA) militarily backed by Turkey and supported by Italy. France is Egypt’s third-largest weapons supplier and maintains a naval base on the coast of Egypt’s close strategic partner the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which itself has been Haftar’s foremost military backer. The hard-power dimension of the Mediterranean’s new ‘Great Game’ has also come to the fore in the eastern Mediterranean naval stand-off between Greece and Turkey, where the Franco-Egyptian partnership against Turkey was put on prominent display in late August 2020 with Franco-Egyptian-Greek joint naval exercises aimed at bolstering Greece’s deterrent capability.

These eastern and central Mediterranean flashpoints have become interlinked, since the 2015 discovery of Egypt’s massive Zohr natural gas field and the resulting plan to pool Egyptian, Cypriot and Israeli gas and use Egypt’s liquefaction plants to cost-effectively market the region’s gas to Europe as liquified natural gas (LNG). Commercially sensible, the plan was a geopolitical timebomb as it excluded Turkey and its pipeline infrastructure to Europe, dashing Ankara’s previously developed plans to use its pipelines to become a regional energy hub. In 2018 the French energy giant Total acquired shares in all seven of Cyprus’s 13 licensing blocks in which Eni is operating, catapulting France to the centre of the eastern Mediterranean energy morass.

Facing strategic isolation in the eastern Mediterranean, Turkey opted for a breakout strategy by forming an overt, formal alliance with the GNA in Tripoli. On 27 November 2019 Turkey and the GNA government signed two Memorandums of Understanding –an agreement on the ‘Delimitation of Maritime Jurisdiction Areas in the Mediterranean’ and another on ‘Security and Military Cooperation’–. The maritime boundary agreement with the UN-recognised government in Tripoli, in Ankara’s view, provides Turkey a legal counter-claim to contest the Exclusive Economic Zones established by Greece’s bilateral understandings with Egypt and Cyprus, upon which much of the development of the Eastern Mediterranean’s offshore natural gas depends.

In contrast to France and Egypt’s covert support for Haftar’s campaign against Tripoli, Turkey opted for an overt security relationship that was activated by the embattled GNA on 19 December 2019. Turkish military intervention enabled the GNA to completely halt Haftar’s 14-month campaign to capture Tripoli and, within six months, Turkish-supported GNA forces managed to push Haftar’s forces 450 km back eastwards to the city of Sirte. The gateway for the GNA to capture Libya’s oil crescent region, the eastern Libyan forces are making their stand in Sirte, the crossing of which Egypt declared, on 20 June 2020, as its red-line that would trigger an Egyptian invasion.

Intense efforts on the part of Germany, the US and the UN have produced a ceasefire, with 21 August 2020 statements by political leaders from each of the warring halves of Libya effectively giving their tacit consent for a demilitarised buffer zone around Sirte. The military force to secure that buffer zone has yet to be determined.

Libya and the Central Maghreb at the heart of the Mediterranean ‘Great Game’

Turkey’s overt military intervention during the first half of 2020 to preserve Libya’s GNA has created an important strategic beachhead for Turkey in the central Maghreb. Having reversed the course of Libya’s civil war and become the GNA’s security guarantor, Turkey is cementing its status as a major power in North Africa. Turkey’s considerable air force presence at the recaptured al-Watiyah air base, located 27 km from the Tunisian border, and its developing naval presence in the GNA coastal stronghold of Misrata have increased Ankara’s clout in Tunis as well as in Algiers. Turkey’s new outsized military presence in Libya now serves as a platform from which Ankara can promote its programme to create Afro-Mediterranean commercial connectivity via the central Maghreb states and Italy, which also backed the GNA and runs a military hospital in Misrata.

Developing energy and commercial connectivity with the central Maghreb states of Tunisia, Algeria and Libya has formed a core shared interest between Italy and Turkey as each seeks to develop a greater economic presence in North Africa and the rest of the continent. Despite Italy’s proximity to the North African coast, France remains the dominant foreign actor in the Maghreb, a region that is increasingly becoming an overland gateway for Euro-African commercial relations with the widespread expansion of high-speed road networks across the continent. While Italy has surpassed France to become Europe’s second largest manufacturer, whose value of sold production exceeds France’s value by approximately one-third, the development of Italy’s economic relations in North Africa and the rest of the continent are constrained by France’s outsized influence on the pattern of Afro-Mediterranean commercial connectivity. Until the advent of French President Emmanuel Macron’s government recent focus on the Mediterranean and his so-called Pax Mediterranea, Paris had been unwilling to allow its relationship with Rome to develop greater parity.

Turkey faces a similar but even more formidable challenge in the Mediterranean basin from its systemic rivals France and the UAE. From 2010 to 2016 Ankara opened 26 embassies in Africa as part of its push to expand Turkey’s economic and political footprint across the continent. Despite making significant trade and investment inroads in Africa, Turkey’s ability to establish its own inter-regional commercial connectivity via North Africa is stymied in the western Mediterranean by Morocco and in the eastern Mediterranean by Egypt –both of which share deep economic and military ties with France and the UAE–.

Italy and Turkey’s geopolitical synergies in the Central Maghreb

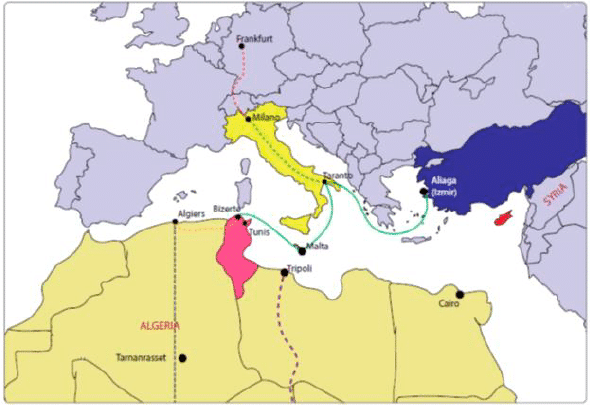

A geopolitical synergy between Italy and Turkey is creating a Turkey-Italy-Tunisia commercial transport corridor that could reconfigure the patterns of trade between Europe, Africa and the Middle East. Slicing across the centre of the Mediterranean, the Turkey-Italy-Tunisia corridor forms an arc of commercial connectivity from the Maghreb to the wider Black Sea. The corridor’s central hub is the deep-sea port of Taranto, located on the Italian peninsula’s southern tip, in the strategic heart of the Mediterranean Sea. Managed by the Turkish port operator Yilport, Taranto’s sea link to Tunisia simultaneously forms the core segment of the corridor’s Europe-to-Africa transport route, by connecting North Africa’s coast to the manufacturing centres of Italy, Germany and northern Europe via Italy and Europe’s high-speed rail systems. From Tunisia’s ports, the corridor can also link via Algeria to the Trans-Saharan Highway, potentially extending Italy and Turkey’s Europe-to-Africa corridor southward into West Africa as far as Lagos, Nigeria.

Italy has long been among the strongest advocates of closer EU-Turkey relations and the two enjoy a very robust trade relationship. After Germany, Italy forms the largest European market for Turkish exports, garnering Turkey US$9.53 billion in revenue in 2019. With the exception of a conflict of interests concerning Cypriot offshore natural gas development, which the two countries had managed to compartmentalise, Italy and Turkey share a broad set of common interests across the wider Mediterranean basin, from the Balkans to North Africa and the Horn of Africa. However, Turkey’s increasing energy exploration in maritime waters claimed by Cyprus during 2019 and Turkey’s subsequent naval stand-off with Greece is forcing Rome to reassess its relationship with Ankara. The securing of Italian economic interests in Libya features as a prominent factor in Italy’s strategic calculus. The Turkish push to become Libya’s leading economic partner may tip the balance.

Italy’s interests in securing Libya’s energy infrastructure

The Italian energy major Eni is the leading foreign energy operator in Libya. Although today considered a private company, the Italian government maintains de facto control over Eni with its 30.33% share.2 Italy’s largest company by revenue, Eni’s drive to expand its market share across the Middle East and North Africa has shaped the parameters of Italy’s foreign policy orientation. In Libya almost all of Eni’s oil and natural gas assets are located in the western half of the country, under the control of the Turkish-backed GNA.3 The geography of Eni’s oil and natural gas assets gives Italy a vital national interest in the preservation of the GNA and the expansion of its authority over western Libya in order to ensure the security of Eni’s energy infrastructure. Italy’s imperative to secure Eni’s considerable assets has left Rome deeply ambivalent over Turkey’s deepening military presence in the country. While providing important short-term benefits, Rome will need to assess the extent to which Libya’s growing dependence on Turkey will render Italy vulnerable to Ankara’s dictates.

Eni is the operator of, and 50% shareholder in, the Western Libya Gas Project that includes the onshore Wafa field on the Libyan-Algerian border, the Bahr Essalam and Bouri offshore fields, the Mellitah complex of treatment plants and pumping stations, and the Greenstream pipeline that transports gas from the Mellitah complex to Sicily. Italy is the only market destination for Libya’s natural gas exports. In 2019 the Western Libya Gas Project supplied 5.4 billion cubic metres of natural gas to Italy, equivalent to 8% of Italy’s natural gas demand.

The good relationship between Italy and the GNA has enabled Eni to maintain stable energy production in the areas under the protection of the militias aligned with the Tripoli government. Since the GNA’s formation under the leadership of Presidency Council head Fayez al-Sarraj, Eni’s exports of Libyan natural gas to Italy have remained relatively constant at around 5.6 bcm annually via the Greenstream pipeline. Neither the pipeline, the Wafa onshore gasfield nor the Mellitah processing and pumping complex on the Libyan coast have experienced significant levels of disruption over the past five years.

Oil production in the El Feel oil field in southern Libya, where Eni has a 33% stake, and the eastern Abu Attifel field, where it has a 50% stake, have fared far worse, repeatedly experiencing extended shutdowns as a result of assaults by various militia factions as they contested for control of these territories. Approximately 85% of Libya’s oil production is onshore, with most of the major oilfields located in sparsely populated areas that are highly vulnerable to militia attacks.

One of the main problems faced by international oil companies (IOCs) operating in Libya is the country’s legal prohibition against IOCs contracting private security to defend their facilities. The result has been a severe disruption of oil production in the country. Libya’s state-owned National Oil Company (NOC) used to field its own Petroleum Facility Guards. However, in the chaos of Libya’s civil war, the NOC’s security forces disintegrated into rival armed factions by 2013, forcing the NOC to attempt to secure ports, plants and fields through convoluted negotiations over the distribution of revenue funds with an assortment of militias. Libya’s largest oil field, the Sharara oil field operated by Spain’s Repsol, has been attacked more than 100 times since 2011. The 2018 assault on Sharara caused the declaration of a force majeurewith the shutdown of the facility resulting in a production loss of 315,000 barrels per day (bpd).

Eni does wield leverage over the GNA on security matters through the provision of power production capacity, as the GNA’s own stability depends on its ability to provide a reliable supply of electricity and electricity-powered municipal services to the residents under its authority. Across both halves of Libya, there is currently an unprecedented power crisis that is generating civil unrest. Libya has a deficit of 2,500 MW of installed power production capacity during peak demand. The percentage of Libyans enjoying access to electricity has dropped to 67% from the pre-civil war level of 81%. The power deficit is aggravated by the oil production shutdown which has caused a shortage of fuel oil to run power plants.

While affecting both sides in war-torn Libya, Tripoli, the seat of the GNA, is the most affected region because of the density of its peak electricity demand. In Tripoli outages can last almost 48 hours. On 11 July 2020 Prime Minister Sarraj, NOC Chairman Mustafa Sanalla and Eni’s CEO hammered out an MOU for Eni’s provision of key parts and technical assistance to the General Electric Company of Libya (GECOL) for the latter to maintain the operation power facilities that provide 3 GW installed capacity accounting for 52% of the country’s total available installed power generation capacity and around 70% of its currently functioning capacity. Additionally, Eni is conducting a development study for the construction of a new gas-fired plant and is providing support for start-up projects to generate power from renewable energy resources.

Within the same time frame as Eni’s negotiations with the GNA, Turkey’s Karadeniz Holding made a bid to send its power-ships to the western Libyan coast to provide the GNA with up to 1 GW of floating power generation capacity. Karadeniz Holding’s proposal came after the heads of various Turkish ministries visited Tripoli to discuss with the GNA government the developing Turkish involvement in Libya’s energy, construction and banking sectors. Turkey’s power plan is reflective of Ankara’s wider push to expand its economic involvement in Libya, a move that potentially threatens Italy’s position in the country’s economy.

From an Italo-Turkish alignment to a Franco-Italian partnership in Libya?

On 13 August 2020 Turkey and Libya signed an economic agreement to resolve outstanding issues arising from Turkish construction projects initiated during the Gaddafi era, estimated at 20% of Libya’s investment projects. The agreement also clears the way for new Turkish investments and increased trade. Turkish construction firms are now eyeing new contracts for Libya’s reconstruction, whose total estimated value is US$50 billion. In 2019 Turkey became the largest exporter to Libya after China, surpassing the EU and earning Turkey US$1.53 billion in revenue. Eighteen days after Tripoli and Ankara signed an agreement to resolving outstanding financial issues, the Central Bank of Libya and Turkey’s Central Bank signed a cooperation agreement aimed at fast-tracking the expansion of economic cooperation between the two countries.

The competition to reconstruct western Libya’s economy and infrastructure will intensify as the GNA consolidates its control. With Turkey being the GNA’s main security provider, Italy now faces the growing concern that cash-strapped Ankara will leverage its built-in advantage with Tripoli to receive reconstruction contracts at Italy’s expense. Ankara’s advantage is multiplied by the financial ability of Turkey’s close strategic partner Qatar to invest heavily in Turkish reconstruction projects in Libya. Already in neighbouring Tunisia, where Turkey is attempting to increase its political influence, Qatar has invested US$3 billion, catapulting Turkey’s close partner ahead of Italy as Tunisia’s second-largest investor.

Events following the 21 August ceasefire do suggest that Italian economic interests in Libya may be vulnerable. An ad hoc commission of the GNA’s Ministry of Transport invited an undisclosed Turkish company to inspect Tripoli International Airport, whose €79 million reconstruction contract was awarded in 2017 to Aeneas, a consortium of Italian companies specialising in airport construction. During the Gaddafi period, Turkey’s TAV Airport Holding had been part of a different multinational consortium hired to work on the airport. The purpose of the Turkish inspection was to provide an assessment to the Libya Airport Authority of the feasibility of the existing contract with Aeneas and explore the possibility of awarding new contracts for the airport’s rehabilitation. Turkey and the GNA are engaged in high-level discussions about Turkish involvement in both onshore and offshore energy projects in Libya. On 13 September 2020 the head of Turkey’s Foreign Economic Relations Board’s Turkey-Libya Business Council claimed that Tripoli was on the verge of signing an agreement to give Turkish energy firms a share of Libya’s oil and natural gas production.

Beyond Libya, Eni’s wider Mediterranean operations in Cyprus and Egypt run afoul of Turkey’s geopolitical agenda in the region. Even in 2017, prior to the Zohr natural gas field coming onstream, Eni’s total revenue from its operations in Egypt was almost equal to the company’s Libya operations. To mitigate its risks after the 2018 run-in with a Turkish naval blockade of one of its drill ships in Cypriot waters, Eni partnered with Total in all of its operations in Cyprus. Concurrently, Eni and Total also joined forces in Algeria, where the two companies formed a consortium with Algeria’s Sonatrach with exclusive rights to explore for energy off Algeria’s coast. Italy and France have deep economic interests in Algeria, and both are facing strong competition from Turkey, augmented now by Ankara’s military presence in neighbouring Libya. Turkey has already made strong inroads in Algeria through US$3.5 billion investments, ranking Turkey as one of the country’s top foreign investors.

In Libya, Total’s presence had been long confined to non-operating stakes in the Sharara oil field and in Al-Jurf, an offshore oilfield off the coast of western Libya. However, in 2018 Total acquired a share in Libya’s Waha oil complex. Total’s expansion of its oil holdings in Libya occurred only one month after it partnered with Eni in the development of Cypriot offshore natural gas. Eni and Total’s recent partnerships in Cyprus, Algeria and Libya form the base of what appears to be a wider commercial symbiosis now developing between Italy and France in the Mediterranean.

Conclusions

Do Spain’s stakes in Libya and the Mediterranean require a policy recalibration?

Spain’s foremost immediate concern in Libya is the security and resumed functioning of Repsol’s assets in the country. Spain’s third-largest company by revenue is the lead operator in two blocks of Libya’s giant Sharara oil field. When not under shutdown due to Libya’s civil war, Sharara is one of Repsol’s most profitable operations worldwide. In 2019 Spain’s oil imports from Libya reached a record high of 170,000 bpd, making Libya Spain’s third-largest oil supplier.

Prior to the civil war, Spanish companies held a significant share in Libya’s infrastructure development. At the signing of Spain’s 2007 bilateral investment and trade agreement with the Libyan government led by Muammar Gaddafi, Madrid announced its expectation for Spanish companies to receive Libyan contracts totalling €12 billion. While likely too optimistic, Spanish firms were poised to play a lucrative role in Libya’s infrastructure development. Indra, for instance, which had built Libya’s air traffic control system, entered into advanced negotiations for a €200 million contract to upgrade Tripoli’s air defence system. Abengoa, which had obtained contracts in 2003 totalling €300 million to upgrade Libya’s electricity transmission system, signed a 2010 memorandum of understanding with the Gaddafi government for the construction of four desalination plants worth €950 million. Indra’s and Abengoa’s agreements, like those of several other Spanish companies were waylaid by the killing of Gaddafi and the ensuing disorder of the Libyan civil war. Madrid needs to ensure that Spanish firms do not become marginalised in Libya’s reconstruction. A disengaged policy of neutrality would likely assure that outcome.

The new alignment emerging from the conflicts in Libya and the eastern Mediterranean directly impacts the foreign policy orientations of Tunisia and Algeria and therefore will increasingly influence the contours of the strategic architecture of the western Mediterranean. Spanish foreign policy faces the urgent task of increasing its diplomatic clout in the Mediterranean and carefully recalibrating the relative balance between its relationships with France, Italy and Turkey; attempting to muddle through by trying to remain politically equidistant from all actors is likely to undermine Spain’s standing among the countries of the Mediterranean basin.

Michaël Tanchum

Professor of International Relations of the Middle East and North Africa at the University of Navarra, Senior Fellow at the Austrian Institute for European and Security Policy (AIES) and Fellow at the Truman Research Institute for the Advancement of Peace, the Hebrew University, and at the Centre for Strategic Policy Implementation at Başkent University in Ankara (Başkent-SAM) | @michaeltanchum

1 The author is grateful to Ignacio Urbasos Arbeloa as well as to Albert Vidal Ribé and Julia Pérez Gómara for their research assistance.

3 Eni’s only asset in eastern Libya is the Abu Atiffel oil field, which is shut down. The field has a potential to produce more than 50.000 bpd of crude oil and condensates.

The Old Castle in Tripoli (Libya). Photo: Ziad Fhema (CC BY 2.0)