Theme

This ARI is based on broader research conducted by the author in Japan as a Visiting Researcher at the Institute of Social Sciences of the University of Tokyo.1 Its aim is to explain in depth the importance of understanding Japanese cultural values in establishing and developing business relationships with Japanese organisations.

Summary

Spanish-Japanese business relationships are not as good as they could be although they have improved in recent years. However, as a result of the specific features of its society and economy, Japan continues to be a country where doing business is often challenging. The traditional values and traits that have guided the Japanese people over the centuries remain in the way in which most of adult people act in public. Dealing effectively with Japanese business people continues to require an in-depth knowledge of the meaning of certain acts reflecting their underlying cultural values and social customs.

The object of this analysis is both to look at the effect of Japanese cultural values on building and maintaining business relationships and to emphasise the importance of understanding cultural values to conduct business successfully in Japan.

Analysis

(1) Introduction

All countries have specific values that are part of their national culture, although inevitably they share some with their neighbours. Thus, they should not be understood in terms of a duality, as in an East-West dichotomy, but as a continuum. It is not only Western business people who usually find difficulties in doing international business with people from Asian countries, but people from different Asian countries themselves know that they have different ways of acting in international business. Hence, although Asian countries share certain cultural values they also have differences, since every culture is unique.

The object of this paper is both to analyse the effect of Japanese cultural values on building and maintaining business relationships and to emphasise the importance of understanding these cultural values if the aim is to do business successfully in Japan.

To that end, the paper will first provide a short overview of the business relations between Spain and Japan. Then it will look at the sources of Japanese cultural values, describing those that the author’s research has identified in the business world and explaining their importance for building and maintaining long-term business relations in Japan. Finally, some conclusions will be presented.

(2) Business relationships between Spain and Japan

Despite the long and good relations between Spain and Japan, established in 1868 with the signing of a Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation and maintained with the restoration of diplomatic relations in 1952, the trade and investment situation is still not up to the levels that could be expected although it has improved in recent years.

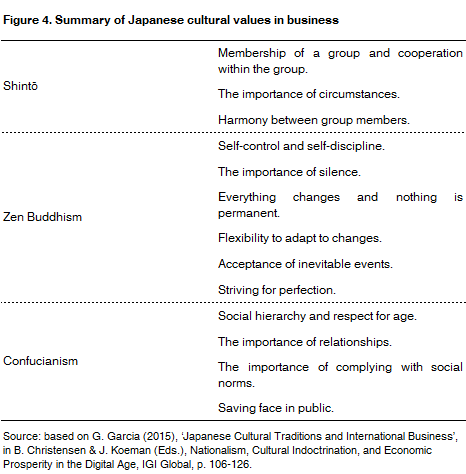

Japan has always maintained a positive trade balance with Spain although the balance between exports and imports has declined over the past few years. As shown in Figure 1, this is a result of both an increase in Spanish exports and a large decrease in imports from Japan, especially since 2009. Thus, the coverage of Spanish imports by exports has risen from 33.48% in 1995 to 99.20% in 2014.

Figure 1. Trade between Spain and Japan (€ thousands)

Source: Datacomex.

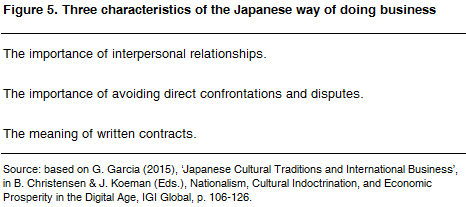

Figure 2. FDI between Spain and Japan (€ thousands)

Source: Datacomex.

As regards bilateral foreign direct investment (FDI), the difference between inward and outward FDI shows that Japan has maintained a large net positive balance (see Figure 2).

Like Spain, trade relations between the EU and Japan have typically shown surpluses in favour of Japan, although the figures have become more balanced in recent years. Nevertheless, as a result of the specific features of Japan’s society and economy, it continues to be a country where doing business is often challenging.

One of the factors causing this situation is an inadequate knowledge of Japanese cultural values. This usually results in misunderstandings, complicates communication and hinders working together. In international business, misinterpretation is not only a question of language but also of good intercultural communication because the same words can have quite different meanings for people of different cultures. In order to communicate adequately with Japanese people it is necessary to learn and understand their culture and customs as well.

The understanding of Japanese cultural values in business does not only consist in having some general knowledge such as, for instance, basic courtesies like greeting with a bow or giving business cards with two hands. This superficial comprehension will not help to do business in Japan. It is also essential to know how Japanese cultural values shape business aspects like making connections and maintaining relationships, adapting to the highly competitive and changing Japanese market or providing an unparalleled level of service.

Japanese people are well prepared about the culture and customs of the country where they want to do business and adapt their own actions to local requirements. Similarly, doing business in Japan requires knowing the local cultural values to understand how to business the Japanese way.

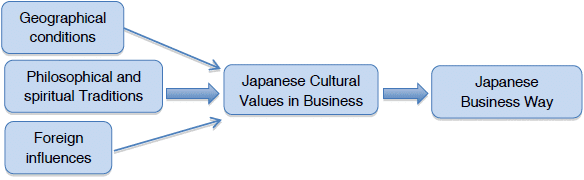

Figure 3. Influences on the Japanese way of doing business

Source: the author.

(3) Sources of Japanese cultural values

In this paper, culture is understood to be the values, norms, beliefs, attitudes and behaviours learnt and shared by a group of people that allow them to see the world in the same way.2 Values are the deepest level of culture and at the most external level are directly observable features, such as the way of doing things. Behaviour can be seen but not the underlying cultural values, thus they can remain unchanged despite being expressed in different ways of acting.

Specific cultural values allow people of each society to know what is appropriate in every situation and thus represent the implicitly or explicitly shared ideas and beliefs about what is good, right and desirable in the community. These accepted ways of doing things determine the norms about how people should conduct themselves and act towards others.

Japanese cultural traditions draw from various sources such as the country’s geographical conditions, the foreign influences received in the course of its history and its spiritual and philosophical traditions.

(3.1) Japan’s geographical conditions. Japan’s geographical isolation, its comparatively small size –being three-quarters the size of Spain– and relatively large population –approximately three times Spain’s– have resulted in its people living in close physical proximity to each other. This has led to a feeling for working in common or in groups, for concern about the feelings of others and for it to be important to be aware of the relative status of individuals. Besides, frequent natural calamities such as typhoons, earthquakes, floods and landslides have fostered a great respect for nature and a desire to live in harmony with it, instead of trying to control it.

(3.2) Foreign influence in Japanese history. Japan has received foreign cultural influences throughout its history, starting with China in the 4th century. By the 16th century, Western European countries such as Portugal, Spain and later the Dutch, had established direct contact with the Japanese until the Edict of 1635 ordered the country’s closing up, forbidding the Japanese from travelling overseas and from returning after having lived abroad. For over 200 years Japan was officially –although not completely– closed and was not officially opened until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. In the mid-19th century Western influence reached Japan mainly from the US. In 1853, four American ships arrived in Tokyo harbour with the purpose of re-establishing regular trade and dialogue between Japan and the West. Contact with the industrialised West brought Japan democracy and a constitutional parliament, access to modern technology and knowledge about the Western lifestyle.

Thus, the Japanese have developed the practice of adopting useful elements of foreign cultures, merging them with local customs and adapting them to Japanese use (iitoko-dori).

(3.3) Japanese philosophical and religious traditions. Philosophical and religious traditions are the beliefs and rules that guide people in their decisions and judgments through life. Japanese philosophical and religious traditions have been developed over the course of Japanese history as the result of a combination of various systems of thought.

Syncretism is the most important phenomenon in Japanese religious history. Shintō and Buddhist beliefs merged when Buddhism was introduced to Japan in the 6th century and Confucianism and Buddhism have always been closely interrelated since it was introduced alongside Zen Buddhism.

This is the main reason why many Japanese people make no clear distinction between their philosophical and religious traditions, beyond mere rites and rituals, and why it is difficult to attribute with any certainty which specific cultural values come from each tradition.

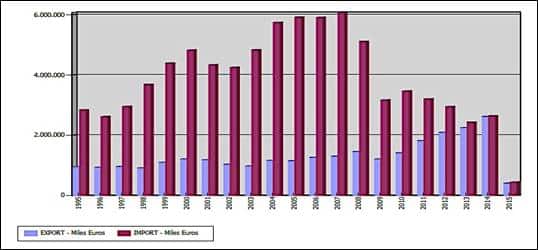

Japanese thought is interested in the reality of this world and places particular value on that which is convenient for the everyday life. Shintō, Zen Buddhism and Confucianism are precisely three traditions that are very much concerned with this present life. Besides, they are probably the traditions that have had the greatest influence on the formation of the Japanese business mind-set.

Certain cultural values in business are directly derived from these three main philosophical and religious traditions and are the basis on which the Japanese assess their own behaviour and that of others.

(4) Japanese cultural values in business

Japanese society is not as homogeneous as usually imagined, with variations according to region, community size, an urban or rural location, education, work or belonging to a minority group. However, all Japanese share specific cultural values and accepted rules of conduct and, hence, there is a high degree of homogeneity in their social customs rather than as regards ethnicity or lifestyle.

Although not all Japanese business people are the same, they conduct themselves in the same way in all specific public situations according to what is socially considered appropriate instead of following what they might think individually.

The author’s experience and research in Japan suggests that it is possible to identify 13 essential Japanese cultural values in business that it is necessary to understand in order to create and maintain business relationships with Japanese people.

These cultural values in business have moulded the Japanese business mind-set and shaped the traits of the Japanese way of doing business way:3

- The importance of relationships. In Japanese traditional culture individuals are considered in the context of their social relationships. Relationships are paramount in Japan’s social structure and a complex of subtle social norms govern every type of interpersonal relations.

- Saving face. Perhaps one of the most important Japanese cultural values is saving face in public situations, as regards both oneself and others. The Japanese tend to try to find an appropriate way to adapt their own wishes to the requirements of others and thus avoid offending or harming their public image.

- Self-control and self-discipline. In a situation of crisis Japanese people will try to retain their self-control and self-discipline no matter what. Self-control means to be able to conceal one’s feelings, emotions and reactions in any situation. Self-discipline is the capacity to pursue what one considers is correct despite temptations to do otherwise.

- The importance of silence. There is a Japanese proverb to the effect that ‘silence is golden’ (iwanu ga hana). Silence is important in Japan as a result of Zen Buddhism. Truth cannot be described verbally but exists only in silence since, although words are necessary to express concepts, language hinders a deeper understanding of the reality that exists beyond words.

- Striving for perfection. Seeking perfection in even the smallest matters is a cultural value that reflects in the usually high level of quality and service in Japan. Perfection should be attempted although it is known that such a thing is not always possible. Thus, mastering technique by constant repetition is insufficient and it is necessary to attempt to reach a state of no-mind (mushin).

- Flexibility to adapt to changes. In Zen practice there is a saying that ‘the most wonderful mind is like water’ because water continuously changes its shape to adapt to any kind environment. Flexibility is achieved by avoiding attachments, ie, by being able to change to adapt to new situations. In a world in constant change it is necessary to let go of both objects and thoughts.

- Everything changes and nothing is permanent. The Japanese are aware of the impermanence and transience of life (mujo) and thus understand that reality is not fixed but subject to constant change. Events are merely transitory circumstances and words are senseless as soon as they are taken out of their original context since the same circumstances will never happen again.

- The importance of circumstances. Circumstances are important because proper behaviour should be expected whatever the circumstances. No action is good or bad in itself, but its meaning and values depend entirely on the circumstances, the purpose, the moment and the place. Good individual acts are those that are best for the community while bad ones are those that are damaging to it.

- Harmony between group members. Harmony is understood to mean avoiding direct confrontations in daily life. Conflicts arise from the relation between one person and others and harmony between group members is the result of finding the appropriate way to adapt one’s own wishes to the requirements of others.

- Membership of a group and cooperation within it. Japanese society gives a great deal of importance to the group or community (ie) and to its social function as the nucleus around which work and life revolve. Thus, the individual exists as a member of a group and his behaviour should be polite and appropriate to promote cooperation within it.

- Social hierarchy and respect for age. The vertical structure of Japanese society is based on the Confucian concept of social hierarchy, which clearly specifies the responsibilities and obligations that govern the relations between individuals. Among the most important are respect for the elderly and deference to seniority.

- The importance of complying with social norms. The Confucianism concept of li extends from codified acts of everyday life to ethical norms for thinking, feeling and acting. It provides every person with a specific position in family, community and society. In turn, this allows everyone to decide what one should or should not do in a particular circumstance and, hence, to decide on the appropriate words and actions.

- Acceptance of the inevitable. Zen teaches that anything, even death, can be faced without fear by accepting its inevitability. Besides, the awareness that events cannot be controlled is inductive to accepting facts as they are.

Figure 4 summarises the specific Japanese cultural values that are relevant in business and shows the three philosophical and religious traditions from which they derive, ie, Shintō, Zen Buddhism or Confucianism. As these traditions have become mixed up through the course of Japanese history, some cultural values are shared and, indeed, may be the result of syncretism.

(5) The importance of understanding Japanese cultural values in business

The traditional values and traits that have guided the Japanese over the centuries remain important today in the way in which most adult people act in public. Dealing effectively with Japanese business people continues to require an in-depth knowledge of the meaning of certain acts that reflect their underlying cultural values and social customs.

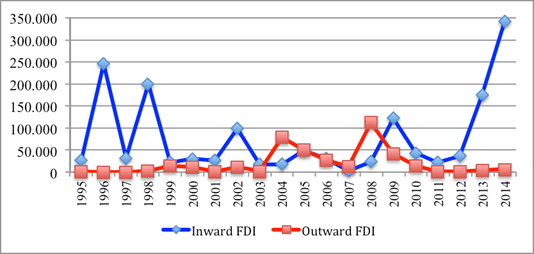

There are three important characteristics of the Japanese way of doing business that are either unknown or give rise to difficulties when in Japan (see Figure 5 below).

(5.1) The importance of interpersonal relationships. An interpersonal relationship (ningen kankei) is an important requisite to doing business in Japan. It entails reciprocity between those involved with the object of promoting their objectives.

Establishing an interpersonal relationship is important because Japanese business people have a greater trust in those with whom they socialise and know than in those merely seeking to do business. They feel more comfortable doing business with people who are friends, and not just acquaintance. Thus, the Japanese spend a lot of time and money in establishing interpersonal relationships before doing business because they need to get to know a potential foreign partner as much as possible in order to understand how they act and be able to interpret their reactions before feeling confident.

After-work meetings are an important part of Japanese business since they allow personal feelings about the business (honne) to be expressed instead of what is considered to be appropriate in public (tatemae). These informal gatherings outside the work environment consist of social activities such as dinners, drinks or karaoke, and help to develop a personal approach, given the more formal attitude of the Japanese at the workplace.

It is important to bear in mind that informal meetings occur not only before and during formal negotiations but also during the subsequent implementation of the joint business strategy. This is because business relationships are still personal in Japan and possible conflicts are resolved in a friendly and non-public way by mutual consultation (hanashiai) instead of litigation.

Japanese people are used to staying in constant personal contact with their business partners and for this purpose they prefer to make personal visits as frequently as possible in order to get to know the individuals in charge and the progress of the business in a more informal way.

In Japan, the initial contacts are not done directly without any references. On the contrary, businesses relationships are established through the appropriate connections and introductions (shokai) by a common friend or even a third party (shokai-sha).

Interpersonal relationships are based on an individual’s relative status or social position in a hierarchy. Besides, the relationship between two individuals of higher and lower status is the basis of Japanese society’s structure. Characteristics such as age, education, work or contacts are the basis for distinctions in status and Japanese business people feel perturbed when status differences are ignored in interpersonal interaction. This relates to the importance of exchanging business cards (meishi), which indicate the place of a person within a company’s hierarchy. The Japanese need to know this to decide how to speak to the other person and what level of politeness to use.

(5.2) The importance of avoiding direct confrontation and disputes. Harmony (wa), understood to be the avoidance of direct confrontation, is an important cultural value of Japanese society and thus avoiding personal confrontation in public is a priority. It is preferable to resolve conflicts through an indirect channel, such as informal meetings, mediation (chūkai) or arbitration (chūsai).

The Japanese are not in the habit of expressing their thoughts in a direct manner. In this way they can avoid hurting other people’s feelings and destroying the harmony in a relationship. They take great care of what they say and how they say it (tatemae), for instance, avoiding saying ‘no’ and instead using less direct expressions such as ‘it is difficult’. Tatemae is the official or public face, the opinions and actions that are appropriate to a specific position and situation, while honne is one’s true feelings or intentions. Harmony is much more appreciated than being frank (ie, expressing one’s opinions or feelings).

In Japan the appropriate behaviour in each public situation depends on the circumstances and is culturally established. In international business, conflicts may be the result of not sharing the same cultural values about what is appropriate or right, and this is critical for assessing sincerity and trustworthiness. A Japanese business meeting is a public situation in which it is necessary to say what should be said according to the accepted social norms (tatemae). On the other hand, personal feelings (honne) are something private that should not be expressed in public.

The vagueness in Japanese communication usually is confusing to foreigners who do not realise that it is complemented by gestures since shared cultural values are the context in which verbal messages are to be understood. Therefore, business people should remember that it is not only the meaning of words that is important but also any accompanying non-verbal communication should be properly interpreted.

Cultural values determine the way in which silence is understood in each society and in Japan silence (chinmoku) is more a manner of communicating what it is important than simply a void between words. Japanese silence may express a broad variety of meanings depending on each particular situation, such as to prevent direct confrontation, to avoid offending others or to express disagreement, since feelings are not usually expressed directly. Thus, misunderstandings can arise when non-Japanese people do not properly understand the meaning of silence in a given situation.

Saving face is a deeply-rooted cultural value in Japanese society and people rarely lose their tempers in public, unless one of the parties has a significantly higher status. The Japanese are more concerned with self-control than with controlling others or the situation, since they are taught not to reveal what they really want to say and to contain emotions with the object of maintaining interpersonal harmony.

The habit of behaving according to what is socially acceptable (tatemae) is an essential element to gain social acceptance, which is the base of group harmony. Japanese business people are oriented to the group they belong to, and this attitude of being concerned about the group’s interests is still the rule in schools and at workplaces in Japan. In public, Japanese business people maintain an attitude of supporting the group even when they personally disagree. Thus, members of the same group act in a similar way.

(5.3) The meaning of the written contract. A contract is a legal medium that describes in written words an agreement between two parties, especially when there no trust has been established between them. Although the Japanese use written contracts, it is usually considered that if there is no interpersonal trust then the mere possession of a signed paper will not improve the business situation. Thus, the traditional Japanese attitude towards the implementation of written contracts is to highlight the business relationship that has been created. A contract is more the mere formalisation of a binding personal commitment to work together than a detailed instrument with fixed clauses that have to be complied with exactly.

The negotiation process does not finish when the participants sign a contract that outlines what is expected of them. In Japan, the signing of the written contract does not mean the end of negotiations since Japanese people believe in changing circumstances (jijō henkō) and the very precise clauses under the signed contract are not considered definite but they are always open to negotiate again, even just after being signed.

Specific terms lose their validity if circumstances change and conditions become unfavourable to any party. They must be adapted to the changes that occur with the purpose of achieving mutually satisfactory outcomes and maintaining a long-term relationship (nagai tsukiai). This is based on the conviction that both parties to a contract should help each other when problems arise because this will be returned in the course of a long-term relationship.

Conclusions:

There are cultural factors that are significant for building and maintaining business relationships in Japan.

It should be borne in mind that the Japanese are well informed and well prepared and that, in reciprocity, foreigners doing business in Japan should have the willingness to understand Japanese cultural values in depth.

It must be highlighted that interpersonal relationships (ningen kankei) are the key factor in Japan and not taking enough time to cultivate them can be interpreted as having scant interest and not being considerate. Trust does not rest on the written contract but on established interpersonal relationships and a long-term strategy, including the commitment to a long-term business relation. This is essential to doing business in Japan.

Harmony, which consists in avoiding personal confrontation and saving appearances in public, is a priority in Japanese business. Likewise, daily contact and the constant fine-tuning of decisions in accordance to circumstances are important.

The high level of quality and service that the Japanese are accustomed to are a reflection of their quest for perfection. High levels are expected even in relatively unimportant matters.

As a final warning, it might be prudent to realise that as a result of the different meanings of contracts based on dissimilar cultural values, non-Japanese business people usually face more problems with their Japanese partners during a contract’s implementation than before it has been signed.

Gloria García

PhD in Economics, Japanese Culture and Business, former Visiting Researcher at Shaken, University of Tokyo, and Lecturer at the ICADE Business School

1 I would like to express my gratitude for the support of Japanese academics and Japanese enterprise promotion institutions during my stay in Japan, especially the Tokyo Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

2 G. Garcia (2015), ‘Japanese Cultural Traditions and International Business’, in B. Christensen & J. Koeman (Eds.), Nationalism, Cultural Indoctrination, and Economic Prosperity in the Digital Age, IGI Global, p. 106-126.

3 G. Garcia (2014), Cultura y estrategia de los negocios internacionales: elaboración, negociación e implementación, Editorial Pirámide, Madrid.