Theme

The COVID-19 crisis could leave long-term scars on economic growth and social development in many low- and middle-income countries. The international financial response should step up its efforts to support countries that did not have enough fiscal space for large-scale support to their households and firms.

Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic provided a painful reminder that many critical development challenges cannot be solved by individual countries working in isolation. There is a clear need for focusing on, and investing in, how to achieve common goals across all countries and challenges, including pandemics, climate change and security, and avoiding long-term scars in lower-income countries.

Development assistance is one of few financing options available to support lower-income countries to deal with the health emergency and support economic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. Even though bilateral aid budgets have not fallen (so far) development partners should maintain their commitments. Most multilateral development banks stepped up their game but some of them need new capital increases or replenishments to sustain the required post-crisis lending. Development partners should also take a different approach to the mobilisation of private sector finance in low- and middle-income countries, moving from the ‘market taker’ approach to ‘market creation’. Finally, development partners should adapt different instruments to different countries to maximise aid budgets in response to the COVID-19 crisis.

Analysis

Introduction

The COVID-19 crisis will create lasting social and economic scars, although these will be felt unevenly both across and within countries. Fiscal policies can help minimise their impact. In the initial phase of the pandemic, policy-makers were urged to do ‘whatever it takes’ to reduce the effects on health systems, households and firms. Throughout the crisis, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) urged governments in advanced economies to maintain expansionary fiscal policies to support economic recovery once the pandemic has been brought under control.

Low-income and middle-income countries, however, have been much more constrained in their ability to shield firms and households from the effects of the crisis and largely rely on external finance. These governments were already more indebted before the COVID-19 crisis struck than in the late 2000s, and even more so towards the private sector (IMF, 2018). While the number of people in low- and middle-income countries that would have been classified as poor as a result of the crisis turned out to be lower than initially estimated, the World Bank still stresses that ‘globally, the increase in poverty that occurred in 2020 due to COVID-19 still lingers, and the COVID-19-induced poor in 2021 continues to be 97 million people’ (World Bank, 2021).

The economic shock has also caused tax revenues and foreign direct investment to fall and limited new grant financing has been made available to support the crisis response. In practice, aid is a small pot of money but many countries rely on it. As a result, many lower-income countries have taken on emergency IMF financing to help weather the initial phase of the pandemic. Looking ahead, a rapid decline in international financing increases the risk that governments in lower-income countries will cut back on spending or will raise taxes even before the virus is fully brought under control. The IMF estimates that low-income countries (as defined as eligible for concessional finance from the IMF) would need to deploy around US$200 billion up to 2025 to step up the response to the pandemic and an additional US$250 billion to accelerate their income convergence with advanced economies (IMF, 2021a).

The crisis is also providing a painful reminder that many critical development challenges cannot be solved by individual countries working in isolation. There is a clear need for focusing on, and investing in, how to achieve common goals across all countries and challenges, including pandemics, climate change and security. Many government spokespersons have often used the mantra ‘we will be safe when everyone is safe’ to justify the need for greater efforts towards international cooperation.

But how have governments scored against these commitments? What has the response of bilateral and multilateral development partners to the COVID-19 crisis been so far? How should development finance evolve to help lower-income countries mitigate the scars of the crisis for a faster and more inclusive socio-economic recovery? We propose five options and recommendations looking at projections for bilateral and multilateral aid, the allocation of, and the rationale for, development finance, and the potential for the private sector to contribute to resource mobilisation in the COVID-19 crisis. This briefing note is not exhaustive regarding all sources of development finance. It focuses on a number of options and channels of international public finance: bilateral aid, grants and loans from multilateral development banks and the role of development finance institutions.

(1) Bilateral aid budgets have not fallen (so far) but commitments should be kept up

In general, quantitative studies have found that aid supply from donors is pro-cyclical –ie, stronger economic growth in the donor country is associated with a higher disbursement of aid (Pallage & Robe, 2001; Round & Odedokun, 2004; Faini, 2006; Bertoli et al., 2008; Frot, 2009; Hallet, 2009; Dang et al., 2013, Fuchs et al., 2014; Dabla-Norris et al., 2015; Jones, 2015). This is to be expected: a stronger economic performance usually means greater tax revenues, implying that donor governments have more resources available and some flexibility in their allocation (Carson et al., 2021).

As was the case with the 2008-09 global financial crisis (GFC), however, grim predictions of a sharp decline in aid in 2020 proved to be wrong. In 2020 most bilateral donors kept their budgets at least constant. Despite the second wave of infections, actual economic growth figures were far better than initially forecasted and most donors saw development cooperation as a tool to tackle the global challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic and to help mitigate some its immediate consequences. Aid from official donors –and they included the largest ones, such as the US, Germany, France and Japan– reporting to the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the OECD rose in 2020. It reached its highest level ever of US$161.2 billion in 2020, despite the crisis triggered by the pandemic (OECD, 2021). For example, in July 2021 the French government approved a legislative bill committing the country to spend 0.7% of gross national income (GNI) on official development assistance by 2025.

The overall response of development partners across regions in 2020 cannot be assessed as of yet, as detailed data will be available only later in the year and is partial at best.

However, in April 2021 preliminary data released by the OECD showed that net bilateral official development assistance (ODA) flows from DAC members to Africa grew by 4.1% in real terms in 2020 compared with 2019 (OECD, 2021). By contrast, net ODA to sub-Saharan Africa fell by 1% in real terms over the same period. The rise in ODA seems to have targeted lower-income and upper-middle-income countries (an increase of 6.9% and 36.1% in real terms, respectively): ODA flows fell by 3.5% in real terms compared with 2019 in low-income countries.

Despite an overall rise in ODA, bilateral donors cannot be complacent. One notable exception is the British government, which announced cuts of 30% to its ODA budget in 2021 compared with 2019. The UK will keep its ODA commitments equivalent to 0.5% of GNI until its fiscal situation improves.

Secondly, despite an initial increase, aid began to fall a couple of years after the GFC. Carson et al. (2021) estimate the fall in ODA would be moderate (about 2.5%) between 2019 and 2021 if donors aim to keep their ODA-GNI ratio constant back in 2019 and beyond. They predict the decline in ODA could reach 9.5% should past relations between growth and aid flows remain constant.

Third, when compared to the fiscal measures taken by national governments to provide domestic relief during the crisis, the increase in ODA is a drop in the ocean. The increase in ODA flows in 2020 across all DAC members has totalled US$8.4 billion, equivalent to one-twentieth of a percentage point (0.06%) of the US$13.7 trillion of fiscal measures taken by national governments to address the pandemic.

Fourth, a growing share of ODA flows also comprises loans –to be repaid in the future–, putting additional pressure on future debt sustainability (see Box 1).

Box 1. COVID-19 and the future of debt sustainability

Even before the COVID-19 crisis began, several borrowing countries were heading towards a debt crisis. For instance, 22 low-income countries (LICs) were classified as being either in debt distress or at high risk of debt distress in 2015. That number had doubled to 44 by 2019 (IMF, 2020b). Over half of LICs were assessed to be at high risk of or in debt distress in 2020 (IMF, 2021b). A longer-lasting and more severe pandemic would trigger an even deeper global recession and push debt levels beyond what could be sustained (Humphrey & Mustapha, 2020).

The G20-led Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) is the main debt relief initiative in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. It has frozen payments on debt service for 73 eligible countries (International Development Association –IDA– countries and Least Developed Countries) until December 2021. However, as it stands, the initiative is net-present-value (NPV) neutral, so debt payments are only postponed. As a result of this NPV neutral approach, the scale of debt relief is relatively small: estimated up to US$5.7 billion in 2020 and potentially up to US$7.3 billion in 2021. Furthermore, debt relief savings are highly concentrated in large economies, such as Pakistan (US$3.6 billion) and Angola (US$1.7 billion). Not all eligible countries have applied for it, either, fearing a lowering in their investment grade by rating agencies. This was the case of the downgrade of the investment rating for Ethiopia as a result of the debt relief measures (Reuters, 2021).

Finally, it is worth recalling that debt relief measures apply to bilateral debt only. Multilateral development banks (MDBs) and the private sector are not involved in the initiative (even though the G20 has also called on private creditors to participate in the initiative on comparable terms). Humphrey & Mustapha (2020) argue that MDBs should not join the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), as it would reduce their capacity to help fund the recovery in return for a relatively small, temporary benefit.

Finally, although vaccinating the world is one of the few challenges where the national interests of donor countries and global development are closely aligned, major donors have spent little on vaccine purchases for low- and middle-income countries through the COVAX facility. Up to April 2021 most donors allocated the equivalent of less than 1% of their annual ODA budgets through COVAX (Miller & Prizzon, 2021). Even the facilities set up by the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) have seen little take-up so far, with a combination of supply becoming available, strict vaccine procurement and approval rules, and hesitation to borrow for vaccine purchases (Hart et al., 2021). Furthermore, international public finance needs to be used not just to address inequities in the distribution of a resource, but also its production. This requires that international public capital flows to countries are based not just on income and the ability to pay for vaccines, but also on the ability to produce. Governments like South Africa may be able to afford vaccine roll-out, but they do not have millions of dollars to finance up-front investment in production (ibid.).

(2) Most multilateral development banks stepped up their game but some of them need new capital increases or replenishments to sustain the post-crisis lending required

The evidence for bilateral shareholders to invest in the multilateral development banking system is compelling –even more so during this unprecedented crisis–. While multilateral development banks (MDBs) share a series of weaknesses in their operational and financing model, they still offer very good value for money and shareholder contributions have a much larger leverage effect than any other financing options. Secondly, MDBs provide countercyclical lending at more affordable rates for most borrowing countries than what markets can offer. Third, multilateral development organisations score better than bilateral donors in the development effectiveness agenda, especially in terms of alignment to national priorities and policy engagement (Mitchell et al., 2021; Humphrey & Prizzon, 2020). Finally, as countries move up the income-per-capita ladder and bilateral donors phase out their programmes, MDBs continue to offer policy advice, technical support and financing.

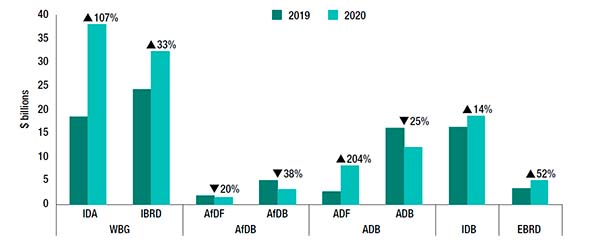

Overall, projects approved at the World Bank and regional development banks increased by 35% between 2019 and 2020, and even more so at the International Development Association (IDA) and Asian Development Fund (Carson et al., 2021). From this snapshot, MDBs have, all in all, been able to mobilise additional resources to help their borrowing countries finance the health emergency and keep economies afloat (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Project approvals by MDBs, 2019 vs 2020

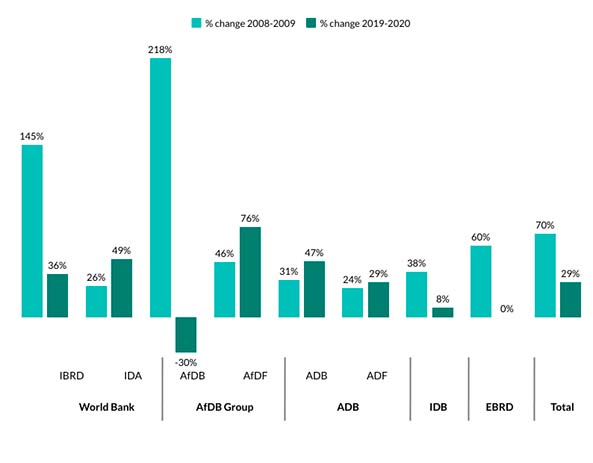

There are a few caveats though. First, while MDBs have scaled up their commitments, actual disbursements are lagging. Morris et al. (2021) show how the World Bank is expected to meet its target for new commitments by June 2021. However, they estimate that disbursements will be only 64% of World Bank commitments. Secondly, lending from many MDBs –for example, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD)– has been far greater in response to the 2008-09 GFC if compared with the early stages of the COVID-19 crisis (Humphrey & Prizzon, 2020; see Figure 2).

Figure 2. MDB lending: global financial crisis vs COVID-19 crisis

Third, lending from MDBs could slow down in 2021 and 2022, the reason being that many MDBs have frontloaded much of their resources in response to the crisis. However, a decrease in MDB lending could be avoided if member states and shareholders were to boost their contributions. The IDA20 replenishment being brought forward by a year and the record-high replenishment of the International Fund for Agricultural Development are encouraging signals, despite the budgetary pressures many donor countries are facing. Another option to boost financing from multilateral organisations lies in the approval of a new tranche of IMF Special Drawing Rights (see Box 2).

Box 2. A new tranche of Special Drawing Rights

We have already discussed the large-scale financing gap to boost the economic recovery following the COVID-19 crisis that low- and middle-income countries face. Lending from MDBs is often constrained and meant for long-term economic recovery. Bilateral aid budgets are under pressure. Attention has therefore shifted towards a new issuance of IMF Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). The SDR is an international reserve asset, created by the IMF in 1969 to supplement its member countries’ official reserves, especially at times of financial crises and liquidity shortages. SDRs do not put pressure on public debt and they are unconditional, ie, not subject to conditions on policy reforms.

In August the IMF Board approved a new allocation of SDRs worth a combined total of US$650 billion. However, at the time of writing this paper there remains much debate about how SDRs can support the pandemic response and recovery, what kind of institutions could be set up to draw on SDRs in the pandemic response, and how SDRs can be directed to those countries most in need, beyond low-income countries, reallocated or ‘recycled’ (Hope, 2021; and Plant et al., 2021).

(3) A different approach to the mobilisation of private sector finance in low- and middle-income countries

The financial commitments of Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) and MDBs to mobilise private finance has grown since 2013 (Attridge & Gouett, 2021). The amount of DFI and MDB commitments to mobilise private finance from 12 selected institutions was just over US$31 billion in 2018, an 8.1% increase from 2013 to 2018.

Before the COVID-19 crisis, sub-Saharan Africa and Europe and Central Asia were the regions with the largest volume of DFI blended concessional finance, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean. While the infrastructure sector dominates investment of DFIs in sub-Saharan Africa, financing and banking is the most prominent sector of new concessional finance commitments in other regions, eg, Latin America as well as Europe and Central Asia (AfDB et al., 2020).

DFI and MDB investment is moving slightly down the country income spectrum, suggesting a small but welcome shift in the risk appetite of these institutions to invest in riskier countries. However, many private investors still shy away from riskier and smaller markets. As the OECD and the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) (2019) pointed out ‘they may have a low appetite for risk given the need to preserve their triple-A credit ratings; they may lack awareness of investable projects; institutional incentives may push them to close deals, leading to a focus on “easier” markets or projects; or their mandates may favour commercial returns’. In addition, investment remains low in LICs and is even lower in the poorest LICs. In 2013 LICs received 5.7% of DFI and MDB commitments; in 2018, it was 6.4% of commitments, an increase of US$340 million in annual investments (Attridge & Gouett, 2021). Mobilisation at scale in markets in lower-income countries will remain difficult; the emphasis should be placed on market creation. Essentially, DFIs and MDBs will need to shift from a ‘market taker’ role responding to individual investment opportunities as and when they arise, to a ‘market maker’ role where DFIs and MDBs invest strategically to build and shape markets.

The initial response of DFIs focused on liquidity support to existing clients addressing cash flows and solvency issues for firms(AfDB et al., 2020). Most interventions concentrated on the supply chain of medical equipment and progressively shifted towards long-term firm restructuring. Several multilateral DFIs that have both sovereign and non-sovereign operations have diverted resources towards budget support and the emergency response away from private sector operations. All in all, the portfolios of some DFIs had been unexpectedly resilient despite the COVID-19 crisis at least in 2020 (Devex, 2021). Expectations point to demand for blended concessional finance and for advisory services and project preparation support to increase in the aftermath of the crisis as firms concentrate on renewal and restructuring (AfDB et al., 2020).

A significant ramp-up of new DFI and MDB investment in 2021 and the near future will, however, be a challenge given the low level of private investment in many low-income countries (LICs) and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) as a result of the crisis. Considering the relatively small ODA flows and the constraints to boost tax revenues in many countries, private finance becomes necessary to help countries finance their national strategies and development. The support for private firms to maintain jobs previously created becomes even more important in countries with limited or no government-funded safety nets, when staff work reduced hours or are being made redundant because of low demand (te Velde & Gouett, 2020).

(4) The use of different instruments in different countries to maximise aid budgets in response to the COVID-19 crisis

Many governments in donor countries are facing unprecedented pressure on spending, which might include cuts in aid spending, as mentioned above. Tough choices lie ahead on how to prioritise aid flows across countries, sectors and policy initiatives, including a shift of bilateral aid towards health initiatives (and delivery directly through bilateral channels). This prioritisation would inevitably include cuts to certain beneficiary countries, and the greater focus on health initiatives means that some sectors will also likely lose out. With overall resources expected to decline while demand potentially rises, getting the most out of aid budgets would require adapting instruments and modalities to country priorities, needs and access to finance, now more than ever (Prizzon & Pudussery, 2021).

Development cooperation programmes and projects also bring other dimensions of international cooperation with them –policy dialogue and knowledge sharing– and these should be prioritised in the fight against a global recession and a pandemic. If the crisis has shown anything, it is that economic shocks and vulnerability are on the rise and becoming more frequent, and this applies to all countries, independent of their income per capita. Countries, even those that have already graduated from development assistance, should be able to apply for additional support at times of crisis and use it flexibly for a much quicker response. One example is the Czech Republic, which informally negotiated a support programme with the EBRD in 2020: investment resumed as of March 2021 (EBRD, 2021). Delayed responses during crises are a recurrent issue for countries that graduated from MDBs, eg, in the case of World Bank support for the Republic of Korea during the East Asia crisis and for Hungary and Latvia during the global financial crisis (IEG, 2012).

We cannot equate the type of development cooperation for LICs or LMICs with economies higher up the income-per-capita spectrum. Policy influence in an upper-middle-income country does not require the same level of financial transfers as it would in an LIC with much larger financing needs. Less expensive instruments like knowledge sharing, peer learning and policy dialogue should be scaled up in upper-middle-income countries. Senior government officials from upper-middle-income countries are indeed asking for far less financial assistance as, while still stretched, their own tax revenues can support national development plans. The share of external assistance in the overall budget is usually very close to zero. Instead, cooperation with development partners is mainly sought for knowledge sharing and peer learning, and to help attract finance from private investors (Calleja & Prizzon, 2019).Knowledge sharing and peer learning are complex and demanding but in principle far less expensive than project and programme implementation. Financial transfers should mainly be channelled to countries that cannot entirely rely on their own tax revenues or cannot borrow from capital markets at reasonable rates.

Conclusions and recommendations

Development assistance is one of few financing options available to support lower-income countries to deal with the health emergency and support economic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. However, politicians and the general public in many donor countries often challenge the rationale for international cooperation –especially the motivations behind investing taxpayers’ contributions in other countries– and the mixed results on the ground, especially in the most challenging and fragile contexts.

We have not covered all the dimensions of financing for development in this briefing note. From the analysis here we summarise the five main recommendations for development partners to improve the allocation, effectiveness and efficiency of development cooperation at the time of the COVID-19 crisis.

- Despite the pressure on their budgets, development partners should keep or even increase their aid budgets –either via bilateral or multilateral channels– and the poorest countries, most affected by the COVID-19 crisis and with limited alternative financing options, must be especially targeted. Why? While development cooperation is a relatively small amount of money in government budgets in many donor countries, it finances and supports areas where the private sector might not have enough incentives to intervene and invest. Development aid can finance projects and programmes tackling global challenges, where other financing resources might not be available or might find it profitable.

- Aid budgets should also prioritise vaccine purchases in the short term and invest in vaccine-manufacturing capacity in low- and middle-income countries in the longer term to build up resilience against future pandemics. Never before has the interest of individual bilateral donors been so closely aligned with the objectives of global development. Low vaccination rates in low- and middle-income countries can threaten progress in advanced economies via the spread of the virus and the greater likelihood of the development of new variants, against which existing vaccines might prove to be less effective.

- Shareholders should support replenishment rounds and general capital increases of multilateral development banks to avoid a fall in the overall resources –at less than market rates– when these will be most needed as countries move away from the emergency and start rebuilding their economies. Investing in MDB capital also offers good value for money when shareholders’ budgets are stretched.

- As the mobilisation of private finance at scale in markets in lower-income countries will remain difficult, the emphasis should be placed on market creation. Essentially, DFIs and MDBs will need to shift from a ‘market taker’ role responding to individual investment opportunities as and when they arise, to a ‘market maker’ role where DFIs and MDBs invest strategically to build and shape markets. Furthermore, DFIs should plan on how to support their clients after the emergency situation in their countries is over. This not only means increasing financial support, technical assistance and project preparation facilities but also expanding modalities and areas of intervention. For example, trade restrictions have shown how fragile global supply chains are, calling for more vertical integration in supply chains, links with local producers and greater digitalisation of firm operations.

- Instruments of development cooperation should be adapted across the income-per-capita spectrum of recipient countries, with an emphasis on knowledge-sharing and peer-learning in the context of upper-middle-income countries.

Financial cooperation with other countries can serve the national interest of a donor country. This is because development cooperation can advance longer-term values of global solidarity and it can also protect the national priorities of donor countries. Every country gains by supporting peaceful societies, protecting the environment and boosting economic development and trade flows across countries.

References

AfDB et al. (2020), ‘DFI Working Group on Blended Concessional Finance for Private Sector Projects’.

Andrews, D. (2021), ‘Can Special Drawing Rights be recycled to where they are needed at no budgetary cost?’, CGD Note, April.

Attridge, S., & M. Gouett (2021), ‘Development finance institutions: the need for bold action to invest better’, ODI report.

Bertoli, S., G.A. Cornia & F. Manaresi (2008), ‘Aid effort and its determinants: a comparison of the Italian performance with other OECD donors’, Working Papers – Economics, Universitá degli Studi di Firenze, Dipartimento di Scienze per l’Economia e l’Impresa, Florence.

Calleja, R., & A. Prizzon (2019), ‘Moving away from aid: lessons from country studies’ODI Report, London.

Carson, L., M. Hebogård Schäfer, A. Prizzon & J. Pudussery (2021), ‘Prospects for aid at times of crisis’, ODI working paper nr 606.

Dabla-Norris, E., C. Minoiu & L.-P. Zanna (2015),‘Business cycle fluctuations, large macroeconomic shocks, and development aid’, World Development, Aid Policy and the Macroeconomic Management of Aid, nr 69, p. 44-61.

Dang, H.-A., S. Knack & F.H. Rogers (2013), ‘International aid and financial crises in donor countries’, European Journal of Political Economy, nr 32, p. 232-250.

Devex (2021), ‘Surprising resilience: DFIs take stock of their COVID-19 response’, April.

EBRD (2021),‘EBRD to resume investing in Czech Republic following COVID-19 pandemic’, press release, 24/III/2021.

Faini, R. (2006),‘Foreign aid and fiscal policy’, CEPR discussion paper nr 5721, Center for Economic and Policy Research, Washington DC.

Frot, E. (2009), ‘Aid and the financial crisis: shall we expect development aid to fall?’, unpublished manuscript, SITE/Stockholm School of Economics, Stockholm.

Fuchs, A., A. Dreher & P. Nunnenkamp (2014), ‘Determinants of donor generosity: a survey of the aid budget literature’, World Development, nr 56, p. 172-199.

Hallet, M. (2009), ‘Economic cycles and development aid: what is the evidence from the past?’, ECFIN Economic Brief 5, European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, Brussels.

Hart, T., A. Prizzon & J. Pudussery (2021), ‘What MDBs (and their shareholders) can do for vaccine equity’.

Hope, C. (2021), ‘Special Drawing Rights: saving the global economic and bolstering recovery in pandemic times’, Eurodad.

Humphrey, C., & A. Prizzon (2020), Scaling up multilateral bank finance for the COVID-19 recovery | odi.org https://odi.org/en/insights/scaling-up-multilateral-bank-finance-for-the-covid-19-recovery/.

Humphrey, C., & S. Mustapha (2020),‘Lend or suspend? Maximising the impact of multilateral bank financing in the COVID-19 crisis’, ODI working paper, London.

IEG (2012), ‘The World Bank Group’s response to the global economic crisis: phase II’.

IMF (2018), ‘Macroeconomic developments and prospects in low-income developing countries – 2018’, IMF Policy Paper, IMF, Washington DC.

IMF (2020a),‘The evolution of public debt vulnerabilities in lower income economies’, IMF Policy Paper, IMF, Washington DC.

IMF (2021a), ‘World Economic Outlook’, April.

IMF (2021b), ‘Macroeconomic developments and prospects in low-income countries – 2021’.

Jones, S. (2015), ‘Aid supplies over time: addressing heterogeneity, trends, and dynamics’, World Development, Aid Policy and the Macroeconomic Management of Aid, nr 69, p. 31-43,

Miller, M., & A. Prizzon (2021), ‘A “shot in the arm” for multilateral cooperation – why international public finance should step up its game for global vaccination’.

Mitchell, I., R. Calleja & S. Hughes (2021),‘The quality of official development assistance’, Centre for Global Development,

Morris, S., J. Sandefur & G. Yang (2021), ‘Tracking the scale and speed of the World Bank’s COVID response’, April Update, Centre for Global Development (CGD) Note.

OECD (2021),‘COVID-19 spending helped to lift foreign aid to an all-time high in 2020’, Detailed Note, April.

OECD/UNCDF (2019), ‘Blended finance in the least developed countries’, OECD, Paris.

Pallage, S., & M.A. Robe (2001),‘Foreign aid and the business cycle’, Review of International Economics, vol. 9, nr 4, p. 641-72.

Plant, M., J. Hicklin & D. Andrews (2021), ‘Reallocating SDRs into an IMF Global Resilience Trust’, CGD note, September.

Prizzon, A., & J. Pudussery (2021),‘From aid to development partnerships: lessons from the literature and implications of the COVID-19 crisis’, Literature Review, London.

Reuters (2021), ‘Moody’s downgrade over G20 common framework hits Ethiopian bonds’.

Round, J.I., & M. Odedokun (2004), ‘Aid effort and its determinants’, International Review of Economics & Finance, Aid Allocations and Development Financing, vol. 13, nr 3, p. 293-309.

te Velde, D.W., & M. Gouett (2020), ‘The role of development finance institutions in supporting jobs during COVID-19 and beyond’, ODI Insight, October.

World Bank (2021), ‘Updated estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on global poverty: turning the corner on the pandemic in 2021?’.

Annalisa Prizzon

Senior Research Fellow at Overseas Development Institute | @aprizzon

1 For example, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) had lent over US$700 billion and generated US$55 billion in net income by 2018, based on shareholder capital of only US$16.5 billion –46 times leverage, compared with between 0.3 and 22 times for blended finance–. The total paid-in capital to IBRD since 1944 accounts for around 10% of aid disbursements in just one year by members of the OECD DAC.