Main ideas

- Between 70% and 90% of modern software comes from open source components. This layer underpins almost all digital systems and is a core part of Europe’s digital supply chain, yet it often lacks sustained funding, security audits and governance aligned with European interests.

- Open source governance influences who maintains projects, who sets priorities and whose needs the software serves. Europe risks relying on infrastructure managed by external actors whose decisions may conflict with its security or economic goals.

- Projects branded as open source can still restrict participation. For instance, GitHub (owned by Microsoft) blocked developers in Iran from accessing public repositories due to US sanctions.

- Europe can secure its own position by funding critical open source components, setting governance requirements and promoting transparent, explainable and secure software. This strengthens Europe’s digital autonomy and reduces the risks of hidden dependencies or externally imposed standards.

- A 10% increase in open source contributions could raise the EU’s GDP by 0.4% to 0.6% and generate over 600 startups.

Analysis[1]

1. What is open source and why does it matter now?

The report EuroStack – A European Alternative for Digital Sovereignty invited Europe’s tech policy community to think about technology as a stack; a layered system with the interaction of raw materials, labour, semiconductors, networks, devices, cloud infrastructure, software, data and AI. Each layer builds on the ones below it. When one part breaks or becomes overly dependent on external control, the whole system becomes fragile.

One of those layers that should be considered by Europe as a potential bottleneck or a catalyser of its strategic goals is software. Software refers to the code and logic that powers digital tools. It is the layer that makes the rest of the system usable, translating hardware capacity and data flows into applications. Software is also a low compute-intensive layer. Europe needs to expand its compute power (and is rightly trying to do so, through the AI Continent Action Plan). At the same time, aiming for greater control over software is a good parallel (and cheaper) strategy.

Within software, open source software is a particularly important aspect to watch. Open source means making the source code freely available, allowing anyone to use, modify and share it under licences that respect these freedoms.

The other side of the coin to open source is proprietary software, where the source code is closed and controlled by the company that owns it. In these systems, only the copyright holder can modify the code, and users rely on the vendor for updates, security patches and continued access over time.

In 2023 global organisations contributed around US$7.7 billion in labour to open source, and nearly 40% of firms reported contributing financially, with dedicated policies, compliance frameworks and security audits already in place.

Why do organisations choose to freely release their work as open source? In many cases, it is to mutualise software development (and its risks). By opening their tools to a broader ecosystem, they share the burden of identifying bugs, maintaining compatibility and securing code that would otherwise be their sole responsibility. It also lets them shape the tools they rely on daily, fix what does not work or build what is missing, now backed by a large, distributed community that can review, improve and extend the code.

We see this logic play out clearly in the European automotive sector. Eleven major manufacturers and suppliers have agreed to build vehicle software together. They are doing it through the S-CORE project, which provides a neutral space with strong technical governance. These shared components are pre-certified for functional safety and built in a modular way, so each company can plug them into its own systems.

This analysis asks how the governance of open source affects Europe’s security, economic leverage and exposure to geopolitical influence. It examines why other major powers already use open source governance to advance national goals and explores what practical steps Europe can take to secure this critical layer of its digital infrastructure.

2. Open source as a vulnerability in the digital supply chain

If software is the connective tissue of Europe’s digital economy, then open source is the lifeblood flowing through it. Modern software applications rely overwhelmingly on free software components. Various studies find that these make up 70% to 90% of total code, including deep layers of indirect dependencies.

The first issue is one of visibility. In any supply chain, especially those involving critical infrastructure, it is essential to know where each component comes from, how it is maintained and what risks it carries. This becomes harder with software, which is intangible. As a result, many organisations do not even know which open source components their systems rely on, or who is responsible for maintaining them. This lack of visibility creates a blind spot that can later manifest as a security risk or as a strategic dependency on actors outside of Europe’s control.

You may see the final product as a proprietary tool controlled by a single company, but the developers who built it often did so with countless open source libraries and frameworks maintained by external communities. This means that even proprietary systems carry the risks, priorities and governance choices embedded in the open source components they rely on. As a result, open source represents a major concentration of risk, often underestimated when discussing digital sovereignty and security.

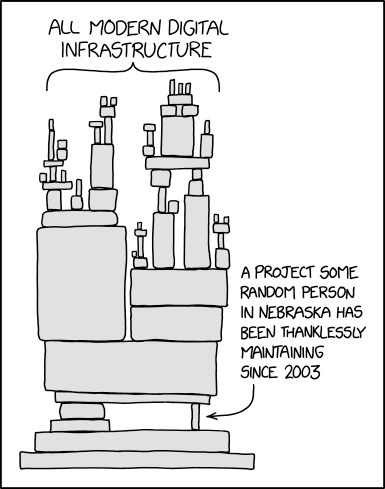

Figure 1. Widely cited satirical visual metaphor of structural dependency in open source software

For example, a study of Kubernetes (a technology widely used across industry) found that two-thirds of its Go dependencies might face vulnerabilities in the medium term, largely due to a lack of maintenance.

The Log4j incident in 2021 showed just how exposed entire economies are to this vulnerability. Log4j was a small, widely used open source library for logging in Java applications. When a severe vulnerability was discovered, it allowed cyberattackers to execute code remotely on countless servers. Because it sat deep inside software stacks, even companies and public agencies who had no idea they depended on Log4j suddenly faced urgent security crises.

Meanwhile, attacks on the digital supply chain continue to rise each year, increasing costs, undermining service continuity and damaging trust.

All of this makes open source a unique kind of vulnerability. It is critical infrastructure, yet largely external to any one country’s direct control. It can be a risk because it is underfunded or because it becomes entangled in geopolitical strategies.

European institutions have started to acknowledge this reality. The Cyber Resilience Act (CRA), which came into force in December 2024, aims to secure the entire digital supply chain by requiring manufacturers and developers to meet baseline cybersecurity standards for products with digital components, including software that relies on open source. Other initiatives, like the AI Act and the Interoperable Europe Act, emphasise openness, standards and cross-border compatibility, and the European Commission’s own Open Source Strategy encourages EU bodies to reuse and contribute back to public codebases. Yet much of this remains too generic, without addressing who maintains this software, how governance decisions are made or what strategic interests shape these choices.

3. The governance layer of open source

‘Open source’ is often treated as if it means the same thing everywhere: free, transparent and community driven. In reality, it can mean almost anything. If you stick to the formal definition (whether a piece of software is released under an open source licence) then the answer is binary: it either is, or it is not. However, power dynamics lie at the governance layer. This layer introduces forms of control and influence that take open source in very different directions, often aligned with national or corporate strategies. That is why governance matters. Governance decides who builds and sustains the software, how decisions are made and whose needs the technology ends up serving.

A key mechanism of open source governance is found in foundations. They coordinate communities, pool funding and manage shared infrastructure. Examples include the Linux Foundation, which oversees critical projects like Hyperledger (used to build blockchain-based products), and the Apache Software Foundation, which maintains widely used software such as Hadoop (for large-scale data storage and processing). Who is behind open source foundations? Some foundations bring together companies from diverse countries, which can distribute influence more evenly. Others are heavily dominated by firms from a single country or sector, which can steer priorities in narrower directions.

One useful illustration of how different governance models shape open source outcomes are digital identity systems (eID). Privacy International has tracked the development of digital identity systems across countries, showing how governance differences shape outcomes even when the source code is open:

- MOSIP (Modular Open Source Identity Platform), developed in India and adopted in countries such as Morocco, the Philippines and Ethiopia, is a fully open source platform. It publishes all its code and documentation and is designed to be modular and adaptable.

- Similarly, Estonia uses X-Road, an open source data exchange layer that connects public and private services across institutions. In 2024 the Estonian government went further and released all state-developed software under open licences.

- Aadhaar (India’s national ID system, providing services to 1.3 billion Indian residents) is often described as open source but includes critical proprietary components. Aadhaar’s structure is opaque. Key modules are closed, audits are limited and technical documentation is not fully accessible.

LLMs raise similar questions. DeepSeek, developed in China, was released as open source, but its training data, documentation and deployment infrastructure remain centrally controlled. The governance model reflects national objectives and positions within China’s broader AI strategy. This breakthrough shows how easily open source can become a strategic tool for influence, depending on how it is governed, by whom and towards what purpose.

4. Has open source become geopolitical?

Because open source is so flexible, it has become a natural tool for geopolitical strategy. States and major corporations increasingly shape open source ecosystems to project soft power through embedded technical standards and to advance their own security or industrial objectives.

In the US, open source is tightly integrated into the commercial software industry. Many widely used tools, such as TensorFlow, Kubernetes and React, were developed by US firms and released as open source. These projects have helped set technical standards that are followed worldwide. The main platforms used to develop and distribute open source software are also US-owned. PyPI and TensorFlow are maintained by entities linked to the Python Software Foundation and Google, respectively. GitHub is owned by Microsoft. It is not an open source platform per se, but it plays an essential role in the open source ecosystem. Developers use it to host code, manage contributions, track issues and coordinate projects across distributed teams. These services are subject to US law. In the last few years, GitHub has restricted access to developers in Iran, Crimea and Syria, blocking them from opening or maintaining repositories. This meant that even if the code was public, affected developers could not participate in the workflow, collaborate or publish their own tools. This directly undermines the principle of open digital infrastructure.

China has taken a different approach. As documented by Alice Pannier, from IFRI, in her Software Power report, open source has become part of China’s strategy to reduce dependency on US technology and increase its international influence. China has created Gitee, a domestic alternative to GitHub, where projects are sometimes censored for violating national content laws.

Another example is OpenHarmony, the open source core of Huawei’s HarmonyOS. After US sanctions cut Huawei’s access to key components, China accelerated the development of this Android-based system, gradually removing Google dependencies. OpenHarmony is now the certified national operating system for IoT devices in China, used across connected appliances, wearables and industrial systems. Given China’s scale as a producer and consumer of IoT technologies, OpenHarmony is gaining significant traction and could soon be shaping global standards.

The Eclipse Foundation has 300+ diverse members. Among its funding members are European actors like SAP, Fraunhofer, Mercedes-Benz and the European Space Agency; US companies such as Microsoft and IBM; and the Chinese firm Huawei, which developed OpenHarmony. The Foundation is now developing Oniro, a European-compatible version of OpenHarmony. Oniro is designed to ensure technical interoperability with Chinese IoT standards without importing Chinese governance models. According to internal sources, the Eclipse Foundation was recently contacted by the Trump Administration with inquiries into its ties to the Chinese government.

The Chinese government has strategically used two key geopolitical levers to gain advantage in the global software race:

- It has supported the rapid growth of thousands of ‘little giants’: small and medium-sized firms focused on mastering critical technologies and components across the software stack.

- It has leveraged diplomatic ties, trade agreements and development aid to embed Chinese software standards abroad. Through infrastructure deals and technical partnerships, China facilitates the adoption of its digital tools in countries across Africa, South-East Asia and Latin America.

These tactics (building national platforms and embedding their standards abroad) allow China to promote the adoption of its own digital architecture.

China is also using open source to mitigate the impact of hardware export controls, particularly in the semiconductor sector. A central example is its embrace of RISC-V, an open-source instruction set architecture (ISA) that allows developers to design custom chips without relying on licensed architectures like those from Intel or ARM. RISC-V offers a modular, royalty-free alternative that lowers entry barriers for innovation in chip design. In 2020 the RISC-V Foundation moved its headquarters from the US to Switzerland, explicitly to avoid geopolitical interference and preserve international cooperation.

The US relies on commercial platforms and network effects. China integrates open source into state industrial policy and digital diplomacy. In both cases, open source governance becomes a channel for influence, especially when it comes to embedding standards and technological dependencies.

The US and the Chinese approaches rely on large-scale participation and the ability to embed technical standards across borders. Europe does not have the same capacity to project influence through massive platforms, commercial scale or tight control over critical digital infrastructure as the US or China. That is precisely why governance matters so much for Europe, as it is the most low-cost way to secure its digital supply chain.

5. What can Europe do to secure its position?

Europe should work towards keeping a critical layer of its digital supply chain secure, reliable and aligned with its needs. As Europe does not have the global platforms or scale of the US or China, the best way to protect its position is to shape open source governance.

The most pragmatic approach may be to de-geopoliticise open source: keep governance structures as open, decentralized and balanced as possible, so that power is not consolidated by actors whose priorities diverge from Europe’s security and economic interests. European policy-makers could explore the following options: (a) funding critical components to shape governance; or (b) building principled tech as a value proposition.

5.1. Funding critical components to shape governance

Most open source software depends on private firms and volunteers that might prioritise ‘flashy’ and revenue-generating features over long-term security, documentation or maintenance. This leaves essential functions underfunded and exposes Europe’s software layer to structural risks. One study found that over two-thirds of external libraries in major Java projects were unnecessary or poorly managed, increasing the attack surface without adding real value.

Public funding is one of the most direct ways Europe can secure this critical layer. Funding must be used to shape governance, to ensure that projects adopt transparent decision-making, security audits, shared stewardship and inclusive structures that distribute influence rather than concentrating it. Germany’s Sovereign Tech Agency already applies this approach, allocating over €23.5 million since 2022 to maintain key open source projects under public reporting and security standards.

Changes in public procurement can be another effective way to achieve this. Procurement frameworks can set conditions: requiring technical steering groups, regular security audits and reporting obligations anchored in European institutions or multi-country foundations, ensuring that no single actor can consolidate control.

The US are already using this strategy. Federal agencies have become major users and buyers of open source software. As explained by Cori Zarek (Deputy Administrator of the US Digital Service between 2022 and 2024) during a seminar on responsible open foundation models at Princeton’s Center for Information Technology Policy, the US government uses its role as a purchaser to shape governance expectations, attaching requirements to how software is maintained, audited and licensed.

In practice, this could turn Europe’s spending into a way to adjust the incentives of open source ecosystems, by funding underfunded and critical components or by setting conditions through software procurement frameworks. That may be the most feasible route to aligning open source governance with Europe’s long-term security and economic interests.

In the context of the growing competition for resources within the ongoing MFF 2028-34 negotiations (driven by defence priorities and fiscal constraints) Europe cannot rely solely on public funding to secure its digital infrastructure. This leads to the next dimension: leveraging Europe’s industrial capabilities as another path to shape its technological agenda.

5.2. Building principled tech as a value proposition

If Europe wants its software layer to gain adoption, it needs to offer a clear value to users. Europe does not have the scale advantages of big tech companies or the tight control that comes from owning core infrastructure. The automatic export of its rules (the so-called ‘Brussels Effect’) has also weakened. That means European-developed software must win on product merit: software that people choose because it solves their problems better. That means defining a unique value proposition that resonates with developers, institutions and companies across borders. If Europe cannot outscale the major tech powers, it must out-design them, by building digital infrastructure that aligns with democratic values and meets users’ growing expectations for accountability and trust.

That unique value proposition could be transparent and explainable software, but what is meant by this?

- Transparency means users can see how a system works. They can inspect the components, understand the logic and audit the data flows.

- Explainability means users can understand why the system makes certain decisions.

Why does this matter? It is difficult to predict tech consumption trends. However, one of the clearest trends is that demand is shifting towards transparent and explainable software solutions, which are also easier to audit and secure, reducing hidden dependencies. Recent industry analyses suggest that by 2027 the global market for AI transparency solutions could exceed US$2.5 billion, reflecting a compound annual growth rate of over 25%. A growing share of users wants systems that are auditable, fair and trustworthy. Scandals involving opaque algorithms, biased outputs and data misuse have increased the pressure for openness.

This approach aligns with ideas set out in the recent report The European Way: A Blueprint for Reclaiming Our Digital Future. The report defines democratic norms, fundamental rights and fair competition as non-negotiable foundations for Europe’s digital model.

Europe already has examples of this strategy. Some open source tools from Europe are already being used globally:

- The explainability library DALEX, developed with European support, helps data scientists understand how machine learning models make decisions.

- The interpretability tools added to Hugging Face’s Transformers (an open source platform with strong European participation) are also being widely adopted.

EU policymakers could shape this ecosystem by using industrial policy tools that support companies building transparent and explainable open source software. This could include targeted grants, procurement rules that favour auditable and secure systems, and regulatory frameworks that reward clear governance and accountability. By doing this, Europe would enable firms and developers to experiment with go-to-market strategies, product architectures and design approaches that all share core principles but adapt to different contexts. As more tools built on these standards gain traction with users and markets, open source products governed under European-aligned rules are more likely to become global defaults. This approach ties Europe’s industrial policy directly to reducing strategic dependencies and embedding trust and oversight into the software layer of its digital supply chain.

Conclusions

Most modern software relies heavily on open source components, yet this layer is often underfunded and governed through structures shaped by the interests of different geopolitical and commercial actors. That makes it both a strategic asset and a potential vulnerability.

The US uses its global platforms and compliance laws to shape participation and technical standards. China ties open source directly to industrial strategy and international partnerships, embedding its priorities into of the digital ecosystems of the countries it trades with. These examples show how open source becomes a tool to secure national interests, influence global norms and build economic resilience.

Europe does not control global developer platforms or enjoy the same industrial scale. However, it can still shape how critical software infrastructure evolves by investing in the right components, requiring governance structures that reflect European security and accountability standards, and supporting tools that are transparent, secure and explainable. This is a practical way to protect Europe’s digital supply chain and limit dependencies that could be exploited for geopolitical or economic leverage.

Strengthening open source governance is a strategy to safeguard Europe’s autonomy. It ensures that the rules and priorities embedded in the software Europe relies on align with its own security needs, regulatory frameworks and democratic principles.

[1] The author gratefully acknowledges the comments and review provided by Judith Arnal Martínez, Daniel Izquierdo Cortazar, Paul Sharratt and Juan Rico.