Theme

There are considerable challenges facing the implementation of the European Defence Industrial Strategy.

Summary

On 5 March 2024, the European Union published its first ever European Defence Industrial Strategy. In the wake of Russia’s war on Ukraine, Europe understands that investing in its defence industrial and technological base is a core way of enhancing Europe’s defence, playing a bigger role in transatlantic burden-sharing and lowering manufacturing and technology dependencies. The Strategy comes at the right time and its stress on defence readiness is welcome, but it asks many more questions than it currently solves. This analysis looks at how the Strategy has been received and probes some of the challenges facing the EU as it seeks to boost its defence industrial base.

Analysis

It is finally here. The first-ever European Union (EU) Defence Industrial Strategy was released in March 2024 in a bid to outline the Union’s approach to the European defence market in the coming years[1]. Taking inspiration from the EU’s first defence strategy, the Strategic Compass, and the 2022 Versailles Declaration, the European Defence Industrial Strategy takes stock of the prevailing geopolitical environment and its effects on the European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB). Although shorter in length than its American counterpart, the European Defence Industrial Strategy makes a cogent case for why governments should invest in the defence sector. In this respect, while there have been many official communications on the European defence industry over the years, this is the first that seeks to: 1) take stock of the war on Ukraine; and 2) reframe the EU’s approach to the European defence market, emphasising one based more on industrial policy rather than market liberalisation. In this respect, the European Defence Industrial Strategy echoes many national strategies, with Spain already recognising in 2023 that ‘the current geopolitical situation and the situation resulting from the war in Ukraine have highlighted the need for sufficient industrial capability in the field of arms production’[2].

Any assessment of the European Defence Industrial Strategy needs to be realistic however: on the one hand, those who support the EU’s efforts in the defence industrial domain should recognise that no single strategy alone will revolutionise the functioning of the EDTIB; and, on the other hand, those more sceptical about the Union’s involvement in this domain should ask why EU member states have successively supported the EU’s role more fervently since the release of the EU Global Strategy in 2016. Indeed, the expectations surrounding the European Defence Industrial Strategy should be managed, all while recognising that – in large part – the Strategy makes a valiant attempt to address the structural weaknesses in the EDTIB and to propose some solutions. All serious assessments of the European Defence Industrial Strategy should recognise that the key components to implementation, as ever, are the EU member states – even if this is hardly an earth-shattering observation. In this sense, the present analysis seeks to uncover some of the intricacies of the new Strategy while also reflecting on what elements were excluded from the final Strategy.

An Analytical and Strategic Consensus?

In many respects, analysts focused far more of their attention on the publication of the European Defence Industrial Strategy than they did with any other recent document on the EDTIB. In fact, examining the majority of articles and papers written by analysts on the Strategy, it is possible to uncover a range of issues which receive near unanimous consensus. Firstly, of the 14 think tank and academic papers studied for this RIE Analysis, all of them state that the Strategy will probably be challenging to implement because of the lack of funding and investment. More specifically, there is agreement that the European Defence Industry Programme (EDIP) proposed by the Strategy cannot have a major effect in the short term, as it is endowed with only a meagre €1.5 billion until 2027[3]. This, analysts agree, will not be enough to meet the fundamental shift in defence readiness touted by the Strategy and nor will it have a sizeable impact on national defence planning[4]. Moreover, certain analysts argue that there is no clarity on what resources will be found for the EDIP after 2027[5], with scepticism that public calls for €100 billion will ever be heeded. Here, one paper specifically underlines how all funding through the EU budget is essentially made up of national contributions, which may hinder the level of ambition for the EDIP[6].

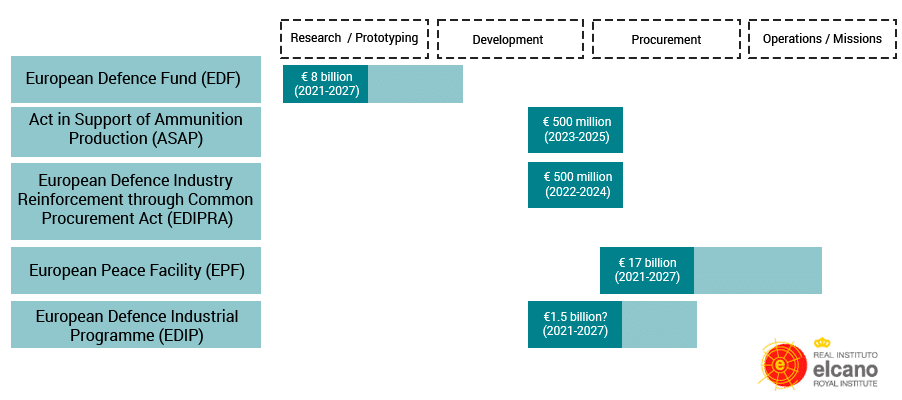

Figure 1: EU-level spending on defence

Secondly, most of the articles analysed also refer to the issue of governance and the role of the European Commission[7]. A rather forceful point of agreement was that EU member states are still in command of security and defence policy, and it was not clear how the existing treaties provide for a more central role for the Commission in defence planning. In this respect, one paper specifically underlines that without treaty change it will be challenging for the EU to take on a larger defence mandate[8]. One of the offshoots of this question is how best to articulate the military and industrial dimensions of the EDTIB[9], with queries remaining about the role of the European Defence Agency (EDA) and the military bodies of the Union such as the EU Military Committee. In many papers there is concern about the EDIP and the Strategy being perceived as a ‘power grab’ by the Commission, although this is offset by papers that underline that the EDIP will not be successful without the full participation of and implementation by EU member states[10].

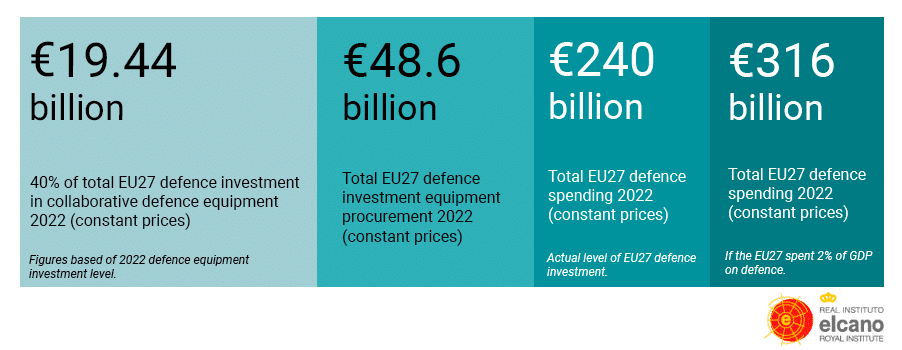

On this point about governance, several other pertinent issues were raised by analysts, such as whether the specific targets outlined in the Strategy were achievable. Indeed, the Strategy states that to enhance long-term and sustained demand in the EDTIB, member states should ‘achieve the goal of procuring at least 40% of defence equipment in a collaborative manner by 2030’[11]. This objective is not entirely new for the EU: since 2007 there have existed non-binding benchmarks on defence and initially one of the goals was to reach 35% for European collaborative defence equipment – so the European Defence Industrial Strategy envisages a 5% increase of this benchmark by 2030. It is worth noting that annual data from the European Defence Agency indicates member states have consistently failed to achieve the 35% benchmark. For example, in 2021 the member states allocated €7.9 billion to collaborative defence equipment – the highest level ever recorded by the Agency – but this failed to meet the 35% target by €7 billion[12]. In 2022 figures, the achievement of the 35% benchmark would have meant a total collaborative investment worth €17 billion out of the €48.6 billion actually invested by member states nationally in defence equipment – increasing the target to 40% would entail collaborative investments worth over €19 billion (see figure 2)[13].

Figure 2: European Collaborative Defence Equipment Investments

Many analysts doubt whether this revised 40% target can be met[14], not least because of the failure by EU member states to meet existing benchmarks for defence in terms of collaborative spending and joint Research and Development (R&D). Furthermore, certain papers focused on the inherent drive in the Strategy towards industrial policy and an insistence on developing and procuring military equipment within the EU, although one paper in particular disputed any such ‘Colbertist revolution’ in defence-industrial policy, as the Strategy lacks any sticks to enforce compliance[15]. Here it was pointed out in one paper that the EU still maintains an addiction to American equipment due to the security guarantees that come with such purchases[16]. Another analysis argued that the EU should not focus on any ‘Buy European’ approach and instead look to support the acquisition of equipment needed today, wherever its origins may lie[17].

Thirdly, a majority of papers also reflected on the participation of third states in the EU defence industrial efforts outlined by the Strategy. One paper called for more attention to be paid to the aspiration of encompassing Ukraine in the EU’s defence industrial initiatives[18], but most papers asked who the EU might consider a close partner in defence industrial matters. In this respect several papers commented that there was no mention of the United Kingdom[19] or such increasingly close EU partners as Japan[20]. Furthermore, several papers stressed how the European Defence Industrial Strategy only played lip-service to the EU-NATO dimension, which these analysts felt was a critical component of defence acquisition, development and standardisation[21].

Finally, some papers referred to other important elements in the European Defence Industrial Strategy, including the fact that Environmental, Sustainability and Governance (ESG) expectations are still a hurdle for unlocking private investment in the defence sector[22]. Here, another paper argued that the Strategy’s clear message on the non-exclusion of the defence sector from ESG investments did not go far enough[23]. On regulatory issues, one paper released after the Strategy stated that there was a need to clarify the Union’s regulatory approach to the defence industry[24]. In advance of the European Defence Industrial Strategy one policy brief made the observation that any Strategy would seriously have to grapple with existing EU directives on defence procurement and intra-EU transfers of defence equipment[25].

‘Buy European’ or ‘Bye Europe’?

As stated above, one of the major concerns with the European Defence Industrial Strategy and the future EDIP is that there is simply not enough money to ensure that it positively impacts the EDTIB. In short, the Strategy’s rightful insistence upon improving European defence readiness will be difficult without funding. True, the Strategy calls for the use of novel sources of finance including frozen Russian assets and a greater role for the European Investment Bank (EIB). However, these new sources of revenue will not be enough to fundamentally shake-up the EDTIB through EU policies. This is why the question of funding the EDIP after 2027 is currently giving rise to ideas ranging from a need to dedicate a larger share of the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) to defence to the creation of European ‘defence bonds’ through the issuance of joint debt, as was the case during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In fact, any discussion about the funding of EDIP is in reality more a structural discussion about how the EU should help finance defence – such a discussion can indeed be seen as the gestational basis for any future ‘EU Defence Budget’, which was recently mentioned in one major political party’s manifesto for the European elections[26]. However, whether the Union ever achieves its own defence budget depends, in the main, on whether EU member states see a benefit in pooling more financial resources at the EU level. It is a well-known fact that contributions to EU defence initiatives represent but a small fraction of what national governments more generally spend on defence. It is also a fact of life that, unless major structural factors force them, national governments are loath to invest a large proportion of national defence spending in collaborative programmes of any kind (EU or otherwise). To the extent that member states do pool financial resources, it is largely in the area of joint capability programmes that occur outside the EU’s (or even NATO’s) defence framework.

Therefore, whether one groups EU investments in defence under the heading of ‘defence budget’ is a matter of semantics. In any case, at present the EU treaties make it difficult to conceive of any EU ‘defence budget’ in the proper sense of the term. A defence budget would assume the full financing of defence research, development, production, procurement and the training and equipping missions in line with a military programme over a defined period of time[27]. In fact, the two key political points at the core of any discussion of EU investments in defence are how large should these investments in defence be in the medium to long term, and who should be in charge of the management of these funds. Indeed, there are risks and benefits associated with entrusting the management of any EU defence investments to supranational institutions such as the European Commission. There are, however, also drawbacks and benefits to maintaining pooled defence spending under intergovernmental control, as indeed the European Peace Facility has highlighted, when governments cannot agree on the fine print of where equipment should be developed or procured.

It should be no surprise therefore that some mixture of both supranational and intergovernmental forms of governance will prevail within the current legal context imposed by the treaties. Arguments about a perceived ‘power grab’ by the European Commission are a natural, and long-standing, feature of European defence industrial policy. Such fears also emerged prior to the creation of the European Defence Fund (EDF). This is why we must wait until the European elections are over to fully assess where governments stand on the Commission’s role. Currently, the proposed defence-industrial plans are vulnerable to political posturing, and there is no more alluring campaign message than governments seeking to curtail the influence of Brussels (especially in defence). The truth of the matter is that, political campaigns aside, we simply do not know what will be developed or lost under the next Parliament and Commission. For example, it remains unclear today whether the EDF and future EDIP will be merged into a single financial instrument. It would be logical to do so given that both tools separately address issues that should be taken together, such as defence research, development and procurement. The question, however, is whether any bid to merge the EDF and EDIP will be based on the aspiration to lower the overall level of investment. Sceptical governments could campaign to lower the financial ambitions of defence industrial tools as a way to reign in the aspirations of institutions such as the Commission.

However, reflections on the European Defence Industrial Strategy should not focus exclusively on finances, because there are several elements in the Strategy that require further assessment. For example, the Strategy refers to the need to gradually create a ‘European Military Sales Mechanism’ to encourage the availability of EU equipment ‘in time and in volume’[28]. Today it would be a mistake to view this initiative as an attempt to copy and paste the US ‘Foreign Military Sales’ (FMS) programme, at least in the way the EU’s mechanism is described in the Strategy and the proposed EDIP regulation. Even if the description of the European Military Sales Mechanism appears in the paragraph after the success of the FMS in the Strategy, what is proposed by the EU cannot be deemed a ‘fundamental tool of foreign policy’, which the FMS is[29]. In fact, what the Strategy proposes is nowhere near as ambitious as the FMS, as the focus is on effectively developing a database on available stocks of equipment in the EU and helping to streamline procurement procedures. Even when taken with the proposed Structure for European Armament Programme, the proposed Mechanism will provide for regulatory streamlining and financial incentives such as a VAT exemption and/or a bonus under the future EDIP.

So even if the language of an enlarged industrial policy has been used in the Strategy, there are clear limits to the Commission’s proposals and what they think member states can (or will) stomach. In this sense, beyond the proposed financial incentives, there are no real steps forward in fashioning an EDTIB that produces defence equipment in Europe for Europeans – if, indeed, this is how ‘Buy European’ should be understood. Accordingly, many of the targets set out in the European Defence Industrial Strategy come with carrots but no sticks. Given the past non-binding targets or benchmarks set by the EU under the auspices of the EDA and/or PESCO, it remains to be seen how far member states are truly convinced of the need to engage in joint collaboration. Perhaps the hope is that an incremental shift to joint development and procurement, even at a lower financial scale, will help build up the muscle memory in the Union for this type of cooperation. Even if this is the case, it will still take much longer to meet the objective of defence readiness, as spelt out in the new Strategy.

Conspicuous by their Absence

Aside from these and other issues, the European Defence Industrial Strategy also avoided any serious engagement with the challenge of arms exports. The easy response here is to point out that arms exports is such a divisive issue among EU member states that it was best not to fully broach the topic; however, one might equally add that no serious EDTIB can be developed without a reflection on exports. To be fair, the Strategy does acknowledge that the EDTIB has had ‘to focus on exports to ensure its viability, resulting in a risk of excessive reliance on third countries’ orders, with the consequence that responding to member states’ orders may be less a priority than honouring third country contracts in case of crises’[30]. The Strategy goes on to call for the level of European defence exports to be preserved, but for greater internal production and supply to meet European capability needs. To this end, the Commission is even proposing an EDIP funding bonus for those member states that collaborate on joint development with common export regimes agreed in advance. The Commission also calls for more streamlining of national export regimes.

Again, however, the Strategy betrays the fact that the European Commission remains relatively limited in the area of conventional arms exports, even if a debate on this topic is long overdue. In fact, one of the pressing issues that is somewhat undersold in the Strategy is the intimate link between domestic demand and exports. As the Strategy points out, Europeans have indeed sought to substitute high levels of domestic demand for defence equipment with exports. Yet, to reverse this logic, what is unclear today is what proportion of domestic demand in the EU should be made to substitute defence exports in the future. The truth is that competition from the US and China for global market share will only increase in the years ahead, and a host of middle-ranking powers will also compete for market share against Europe. This is not just a question of how to enhance Europe’s defence industrial competitiveness abroad in the future but also about how the common or joint defence projects the EU seeks to support in the years ahead will make up for any loss in the global share of exports. As a prerequisite, any common EU procurement projects will require a sizeable upfront demand from member states to ensure cost-management and manufacturing sustainability.

Aside from the issue of arms exports however, the Strategy may have missed an opportunity to link defence industrial initiatives with the Union’s broader economic and technology policies. For example, one quote from the Strategy states that the EDTIB ‘also contributes to the Union’s wider economic security, as the EDTIB is a key driver of technological innovation and resilience across our societies’[31]. Yet this claim only really holds water if the Union ties together its defence industrial initiatives with other geoeconomic tools and initiatives. So, while the EU has striven to link its defence industrial policy with space and dual-use initiatives in the past, there are some glaring gaps in policy linkage for other areas. There is, for example, little reference to how EU trade policy can be used to gain and leverage access to the critical raw materials needed for defence production. What is also missing is how defence links with EU measures in support of artificial intelligence and emerging and disruptive technologies (EDTs) more broadly, where the Commission has made significant advances.

Concluding Remarks

For the first ever European Defence Industrial Strategy, the drafters should be pleased that they managed to publish a focused strategy that clearly identifies the structural challenges facing the EDTIB. There was a risk before the Strategy was released that the drafters would simply stitch together various Commission initiatives and communications that were already well developed. What was published instead was a text that offered a sense of the political-military purpose behind and the ambition for the need to develop the EDTIB. The way in which the Strategy links these challenges with a need to enhance Europe’s defence readiness is also inspired, and this in many respects is the codification of the EU’s growing seriousness in defence policy. The Strategy has essentially reiterated the growing consensus among EU/NATO member states and close partners (specifically the US) that Europe needs to reverse the deterioration of its defence industrial and technological base. As Spain’s 2023 Defence Industrial Strategy argued, investment in defence marks the ‘construction of strategic sovereignty, the reduction of dependencies and the design of a sustainable model for growth and investment’[32].

Clearly, expectations for closer EU defence-industrial cooperation have to be realistic and even the drafters of the Strategy recognise that sustained and ambitious levels of funding and political commitment from the member states are required. The Strategy has also fired the starting pistol on a longer process, the outcome of which will take several years to emerge: namely, the level of financing the defence industry will receive under the next EU budget post-2027. The interval between the present day and 2027 is both a long and short period of time: ‘short’ in that after the European elections attention will immediately turn to the MFF, but ‘long’ in that other geopolitical events can and will emerge by 2027. In this sense, the Strategy is absolutely right to insist on defence readiness, even if the Union is not quite ready for this yet in a material sense.

[1] European Commission/High Representative, “Joint Communication on a New European Defence Industrial Strategy: Achieving EU Readiness through a Responsive and Resilient European Defence Industry” (accessed 24 March 2024).

[2] Spain Ministry of Defence, “Defence Industrial Strategy 2023”, p. 49 (accessed 14 April 2024).

[3] Clapp, S. (2024) “EU Defence Industry Programme and Strategy”, European Parliamentary Research Service, March 2024 (accessed 20 March 2024); and ARES Group (2024) “What Future European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB) Do We Want/Need?”, 7 March 2024 (accessed 15 April 2024).

[4] Bergmann, M., Droin, M., Martinez, S. and Svendsen, O. (2024) “The European Union Charts its Own Path for European Rearmament”, CSIS Commentary, 8 March 2024 (accessed 13 March 2024); and Nones, M., Marrone, A. and Ravazzolo, G. (2024) “Lo Stato del processo di integrazione del mercato europeo della difesa”, IAI Osservatorio di Politica internazionale, 18 March 2024 (accessed 27 March 2024).

[5] Besch, S. (2024) “Understanding the EU’s New Defense Industrial Strategy”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 8 March 2024 (accessed 14 March 2024); and Op.Cit. Bergmann, et al. (2024).

[6] Arteaga, F. (2024) “La Estrategia Industrial de Defense de la UE: señalar la luna, mirar el dedo”, Elcano Roya Institute Comment, 12 March 2024 (accessed 14 March 2024).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ostanina, S. and Tardy, T. (2024) “Turbo-Charging the EU’s Defence Industry and Security Posture”, Hertie School/Jacques Delors Centre Policy Brief, 17 March 2024 (accessed 18 April 2024).

[9] Op.Cit., Nones, Marrone and Ravazzolo (2024).

[10] Maslanka, L. (2024) “The Imperative of Cooperation: The European Commission’s Strategy for the Defence Industry”, Centre for Eastern Studies OSW, 18 March 2024 (accessed 23 March 2024).

[11] Op.Cit., (2024) “European Defence Industrial Strategy”, p. 10.

[12] European Defence Agency (2022) “Defence Data 2020-2021: Key Findings and Analysis”, p. 15 (accessed 14 April 2024).

[13] European Defence Agency (2023) “Defence Data 2022: Key Findings and Analysis” (accessed 14 April 2024).

[14] Op.Cit., Arteaga (2024); Mason, P. (2024) “Europe’s Defence Industrial Strategy: Beyond the Rhetoric”, Social Europe, 15 April 2024 (accessed 16 April 2024); and Grand, C. (2024) “Opening Shots: What to Make of the European Defence Industrial Strategy”, ECFR Policy Alert, 7 March 2024 (accessed 10 March 2024).

[15] Faure, S.B.H. and Zurstrassen, D. (2024) “The EU Defence Industrial Strategy: The ‘Colbertist Revolution’ will Have to Wait”, LUHNIP Working Paper Series 1/2024, LUISS Guido Carli (accessed 15 April 2024).

[16] Op.Cit., Besch (2024).

[17] Op.Cit., Maslanka (2024).

[18] Op.Cit., Clapp (2024).

[19] Op.Cit., Besch (2024); Sabatino, E. (2024) “EU’s Grand Defence Industrial Plans Risks Fizzling for Lack of Money and Unclear Procedures”, IISS Military Balance Blog, 18 March 2024 (accessed 26 March 2024); and Mawdsley, J. (2024) “The EU Defence Industrial Strategy: Solution to or Distraction from Europe’s Rearmament Dilemma?”, UK in a Changing Europe, 9 April 2024 (accessed 11 April 2024).

[20] Wolff, G. (2024) “The European Defence Industrial Strategy: Important, but Raising Many Questions”, Bruegel, 19 March 2024 (accessed 26 March 2024).

[21] Op.Cit., Grand (2024).

[22] Op.Cit., Maslanka (2024).

[23] Op.Cit., Wolff (2024).

[24] Ibid.

[25] Fiott, D. (2024) “In Whose Interests? Regulating Europe’s Defence Industry and the Politics of Exemptions”, CSDS Policy Brief, 3/2024, 19 February 2024 (accessed 20 March 2024).

[26] European People’s Party (2024) “EPP Manifesto 2024” (accessed 13 April 2024).

[27] It was Jean-Pierre Maulny who first tabled the idea for a “European Military Programming Law” to better structure EU investments in defence. See: Maulny, J-P. (2020) “No Time Like the Present: Towards a Genuine Defence Industrial Base for the CSDP?”, in Fiott, D. (ed.) The CSDP in 2020: The EU’s Legacy and Ambition in Security and Defence (Paris: EU Institute for Security Studies) p. 133 (accessed 10 April 2024).

[28] Op.Cit., (2024) “European Defence Industrial Strategy”, p. 13.

[29] US Defense Security Cooperation Agency, “Foreign Military Sales (FMS)” (accessed 4 April 2024).

[30] Op.Cit., (2024) “European Defence Industrial Strategy”, p. 5.

[31] Op.Cit., (2024) “European Defence Industrial Strategy”, p. 2.

[32] Op.Cit., (2023) “Spain Defence Industrial Strategy 2023”, p. 10.