Theme[1]

Argentina’s new monetary-exchange rate regime, currently transitioning towards a system of currency competition, a floating exchange rate and inflation targeting –similar to the frameworks in place in Peru and Uruguay– will require periodic foreign exchange market interventions by the Central Bank. In the long term, as confidence in the peso is restored, the economy is likely to undergo a slow, gradual and natural process of de-dollarisation, which stands in contrast to President Milei’s repeatedly stated goal of full (and endogenous) dollarisation.

Summary

Exchange rate regime: In Phase 3 of the stabilisation plan, Argentina adopts a currency band ranging between a floor of 1,000 and a ceiling of 1,400 pesos per dollar (adjusted by +1% monthly the ceiling and -1% the floor), while the peso to float within these limits. The Central Bank (BCRA) will intervene without sterilising: it will buy dollars at the lower end of the band (expanding the money supply) and sell at the upper end (contracting the money supply), in addition to conducting the open market to adjust M2 to its indicative target and set the policy interest rate.

Full currency competition: Most restrictions on the use of the dollar are eliminated: the end of the cepo (capital controls), an incentive regime for the repatriation of capital held abroad, equal conditions for opening and operating accounts in foreign currencies, the ability to make payments through QR codes and automatic dollar-denominated debits, the option to invoice and set prices in any currency, and soon a decree that will allow transactions with dollar bills stored ‘under the mattress’ without penalties.

Advantages of a mixed exchange rate regime over a fixed or pure float: It provides predictability and anchors expectations (by limiting ex-ante exchange rate volatility), flexibility to absorb external shocks (with an initial 40% band), and the possibility of intra-band interventions to moderate fluctuations that could destabilise expectations.

Need for exchange rate intervention: In a highly dollarised economy like Argentina, where the exchange rate is key to price formation and inflation expectations, the Central Bank (BCRA) will need to intervene regularly to moderate exchange rate fluctuations and prevent them from directly impacting the general price level.

Dollarisation or de-dollarisation? While currency competition will boost the use of the dollar in the short term, the experience of Peru and Uruguay show that after several years of single-digit inflation and a sustained recovery of credibility in the national currency, the economy tends to de-dollarise slowly, gradually, and naturally. A total –and endogenous– dollarisation, which is the declared goal of President Milei, is not only unnecessary but also difficult to achieve if the stabilisation plan succeeds. In other words, paradoxically, the success of the stabilisation plan would become an obstacle to achieving the goal of full dollarisation of the economy. The ‘law of gravity’ works in the opposite direction.

Analysis

1. The new Argentine monetary-exchange regime

In the recently agreed programme with the IMF, Argentina plans to converge towards a regime of free currency competition with a floating of the peso against the dollar, similar to the one implemented in Peru and Uruguay.

1.1. Moving exchange rate band

During the transition, a moving exchange rate band regime is adopted, with an initial floor of 1,000 pesos per dollar (which will decrease at a rate of 1% per month) and an initial ceiling of 1,400 pesos per dollar (which will increase at a rate of 1% per month), allowing for floating within this band. The adoption of this new exchange rate regime was accompanied by the lifting of exchange controls (the so-called cepo in Argentina), with some exceptions.[2]

The new exchange rate regime will function as follows:

- When the exchange rate operates at the lower end of the band, the Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA) will purchase dollars in exchange for pesos. This intervention will not be sterilised, resulting in an expansion of the peso supply in circulation. In this way, the increased demand for liquidity in pesos will be met as the economy remonetises with the expected decrease in inflation –projected to be 20% in 2025– and economic growth –expected to be 5.5% in 2025–.

- On the other hand, when the exchange rate operates at the upper end of the band, the Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA) will sell dollars in exchange for pesos. This intervention will also not be sterilised and will result in a contraction of the peso supply in circulation in circumstances where the demand for liquidity in pesos decreases.

- Within the band, the exchange rate will float and be determined by market conditions. For the purposes of conducting monetary policy within the floating band, the Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA) will monitor the evolution of monetary aggregates, particularly private transactional M2, due to its close link with the inflation rate.[3] To ensure the desired trajectory of transactional M2, the BCRA will carry out open market operations to inject or absorb peso liquidity –using its portfolio of Treasury securities– and will set the policy interest rate accordingly.[4]

- Finally, the BCRA may intervene within the band to purchase US dollars in line with its macroeconomic objectives and the goal of accumulating international reserves (IR), as well as to sell dollars during periods of unusual volatility.

1.2. Currency competition

Since the stabilisation plan was launched in December 2023, the Milei administration has gradually adopted measures aimed at facilitating currency competition, that is, creating a regulatory framework that places the US dollar on equal footing with the peso.

Without aiming to be exhaustive and organising them conceptually rather than chronologically, the following is a series of measures implemented for that purpose:

- Elimination of most restrictions on dollar purchases, effectively putting an end to foreign exchange controls (known in Argentina as the cepo cambiario).

- Tax amnesty for undeclared capital, which channelled nearly US$20 billion into the financial system, increasing the supply of dollars available for private transactions.

- Equal conditions for opening savings accounts in foreign currency (US dollars and other currencies), removing the restrictions imposed in 2020 on foreign currency deposits, so that any bank client can now access a dollar account under the same requirements that apply to peso accounts.

- Authorisation for businesses and users to make automatic debits in US dollars.

- Implementation of an interoperable QR system for debit card payments in dollars.

- Authorisation for virtual wallet systems to operate in dollars, allowing users to pay for goods and services using dollar balances. All virtual wallet providers must be able to read and process any QR code, thereby ensuring that both users and businesses can make payments in the currency of their choice (pesos or US dollars) without technological barriers.

- Authorisation for individuals and companies to enter into contracts, issue invoices, and carry out transactions in US dollars, euros or any other currency without restriction (except for tax payments, which must still be made in pesos).

- Authorisation for the prices of goods and services to be displayed in US dollars or another foreign currency, in addition to the local currency (pesos), clearly stating the total and final amount payable by the consumer.

- Lastly, at the time of writing this paper, the government is preparing a decree to ease restrictions on the use of physical US dollars for purchases and transactions, without incurring currency or tax penalties. The goal is to facilitate the remonetisation of the economy by enabling the use of dollar cash savings that Argentines keep ‘under the mattress’ in significant amounts.

In other words, the new regime formally acknowledges what has already been happening de facto in Argentina: the US dollar already plays a central role in the economy, in the formation of prices and inflation expectations, as a means of payment, in household savings and in government borrowing.

1.3. The advantages of the new exchange rate regime vs a fixed or freely floating rate

This mixed regime offers, firstly, greater predictability and stability compared to the volatility of a floating system without bands.

Secondly, it provides an anchor for expectations, as it limits, ex-ante, the extent of the float, in contrast to a managed floating regime with occasional interventions. This is especially relevant in a country where the exchange rate is a key determinant of price formation in the economy.

Additionally, unlike a fixed exchange rate regime, it has sufficient flexibility –a 40% bandwidth between the lower and upper limits, which will increase month by month– to accommodate unforeseen external shocks (eg, a deterioration in commodity prices or more restrictive international financial conditions) that may require a depreciation of the equilibrium real exchange rate.

Finally, it includes the possibility of intervening within the band, which in our view will not only be an option but also a necessity to keep inflation expectations anchored.

2. Monetary and exchange rate policy in dollarised economies

To place Argentina on the dollarisation map, we will use as comparators the six most important economies in Latin America with inflation targeting regimes and floating domestic currencies: Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Uruguay. The latter two are particularly relevant as they are economies that operate in currency competition and –at least on paper– under a floating exchange rate regime, a regime similar to the one Argentina aims to converge to.

Argentina’s starting point is one of very low monetisation and a relatively small financial system compared to the group of countries chosen for comparison. A low level of monetisation is common in economies with high inflation, such as the Argentine case (Figure 1a). These low levels of monetisation correspond to financial depth levels that are the lowest in the region (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. Monetisation and banking system

2.1.Measures of dollarisation

There are various forms of dollarisation. To simplify our analysis, we will use two: financial dollarisation –the use of the dollar for deposits and granting credit– and price dollarisation, meaning the use of the dollar as a unit of account for setting domestic prices.

2.1.1. Financial dollarisation

In terms of dollarisation of credits and deposits, Uruguay and Peru lead the region. On the other hand, despite the multiple restrictions on foreign currency transactions still in place at the end of 2024, financial dollarisation in Argentina ranks third in the region, above Chile, Mexico, Brazil and Colombia (Figure 2a). Furthermore, if we focus only on public debt, Argentina has the highest level of dollarisation in the region, at 43%, partly explained by the low depth of its domestic financial market and its high reliance on foreign debt, which, due to its history of inflation and devaluations, is mainly denominated in dollars (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Financial dollarisation

2.1.2. Price dollarisation

In the first study of its kind, Drenik & Pérez (2021) use data from the leading e-commerce platform in Latin America, Mercado Libre, which operates in multiple countries across the region, to analyse the currency in which prices are set in domestic markets for consumer goods, vehicles, and real estate. The fact that Mercado Libre operates in several Latin American countries also allows for comparative analysis.

For the sample of countries in their analysis, Drenik & Pérez (2021) show that, on average, Uruguay and Peru lead in the percentage of prices set in dollars –in the rest of the countries, there are restrictions on the use of the dollar as a unit of account–. However, if we focus solely on the dollarisation of real estate –where there is more freedom to write contracts in dollars– Argentina ranks second in the region, with more than 70% of these assets priced in dollars (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Price Dollarisation (% of prices set in US$)

Another interesting finding from the research by Drenik & Pérez (2021) is that there is a high correlation between the proportion of prices set in dollars and the proportion of bank deposits denominated in dollars: countries with high levels of dollarisation of deposits tend to have higher levels of dollarisation of prices. This strong correlation is present in each of the three markets analysed: consumer goods (66%), vehicles (64%) and real estate (66%).

Additionally, given the evidence showing that dollarisation of bank deposits is highly correlated with dollarisation of bank credit (Tobal, 2018), it can be concluded that financial dollarisation and price dollarisation are often two sides of the same ‘coin’.

3. Monetary and exchange rate policy in economies with high dollarisation

Monetary and exchange rate policy in economies with high levels of dollarisation has specific characteristics that anticipate the type of monetary-exchange rate regime in which, beyond formal definitions, Argentina will operate.

First, in dollarised economies, the domestic monetary policy rate has a very limited impact on bank credit, as documented by Amado (2025),[5] using individual bank data from the region. Figure 4a illustrates that, for banks with high dollarisation of credit, the impact of a 1 percentage point increase in the US policy rate on the volume of credit granted increases persistently through time, reducing credit by 5% in the seventh quarter after the interest rate hike. In contrast, a 1 percentage point increase in the domestic monetary policy rate has no significant impact on bank credit in banks with high dollarisation.

On the other hand, Figure 4b shows that, for banks with low credit dollarisation, US monetary policy has no significant effects on credit volume at any of the analysed time horizons, whereas domestic monetary policy negatively and significantly affects credit volume starting from the first quarter after the interest rate hike.

Figure 4[6]. Monetary policy in dollarised vs non-dollarised economies (impact of a 1 percentage point increase in the US monetary policy rate and the domestic monetary policy rate on bank credit volume)

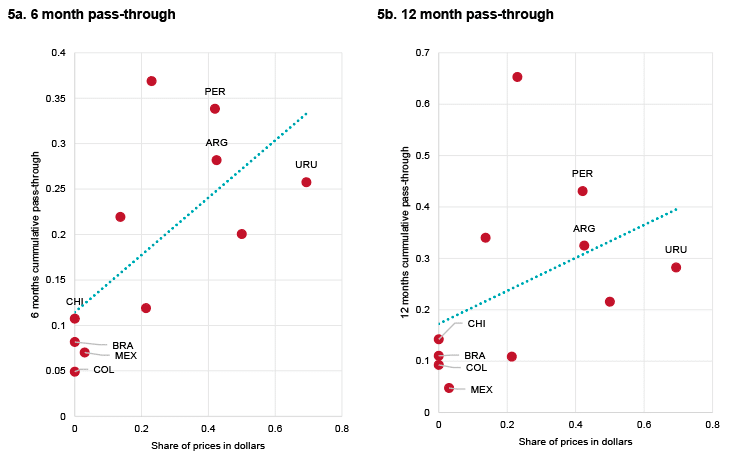

Therefore, in dollarised economies, the domestic interest rate is an imperfect instrument for controlling aggregate demand and inflation, and thus for anchoring expectations. Secondly, in economies with a higher degree of price dollarisation, the exchange rate pass-through to inflation is greater. Drenik & Pérez (2021) find a strong positive relationship between the degree of dollarisation in an economy and the exchange rate pass-through to inflation across all time horizons (see Figure 5). In fact, the six-month exchange rate pass-through to inflation in countries with low price dollarisation such as Brazil (8%), Mexico (7%), Colombia (5%) and Chile (10%) is significantly lower than in countries with high price dollarisation like Peru (34%) and Uruguay (26%).

Figure 5. Price dollarisation and exchange rate pass-through[7] to inflation

In other words, central banks in highly dollarised economies cannot afford to ignore exchange rate fluctuations, as they are a very important determinant of price formation and inflation expectations.[8]

Thirdly, and as a consequence of the above, dollarised countries tend to exhibit lower exchange rate volatility, as documented by Drenik & Pérez (2021).

The high pass-through, combined with the weakness of the policy interest rate as an anchor, effectively leads dollarised economies to adopt a managed float regime. For example, Peru and Uruguay have inflation targeting frameworks and floating exchange rate regimes, but they intervene in the foreign exchange market to dampen volatility and anchor expectations. In other words, not only the interest rate but also foreign exchange market intervention serves as an additional instrument of monetary policy. Indeed, central banks with inflation targeting in dollarised economies seek to prevent exchange rate volatility from causing undesirable fluctuations in the price level, which could un-anchor expectations and make it difficult –or costly– to meet the inflation target.

4. Is Argentina moving towards full dollarisation?

Measures aimed at gradually facilitating currency competition –that is, creating a regulatory framework that places the dollar and the peso on equal footing– will likely lead to an immediate increase in the use of the dollar as a unit of account, means of payment, and store of value.

However, the stabilisation plan launched by the administration of Javier Milei aims to reduce inflation to single digits, which could eventually contribute to a gradual recovery of confidence in the local currency.

Although it is possible that Argentina may converge toward an equilibrium in which the dollar becomes the preferred currency for everyday transactions and financial contracts –that is, an endogenous dollarisation– the experience of other countries that went through inflationary crises followed by successful stabilisation plans suggests that, in the medium and long term, de-dollarisation is a more natural consequence of price stability and the recovery of confidence in the national currency.

The cases of Peru and Uruguay are illustrative of two highly dollarised economies that implemented successful stabilisation plans. Figure 6 shows that in both countries, whose stabilisation programs began in 1990 and 1991 respectively, it took several years for inflation to fall below 10% after dropping below the 100% threshold: five years in Peru and seven in Uruguay. This does not imply that Argentina will follow an identical path, but it does demonstrate that restoring credibility in the local currency is a slow process.

Figure 6. Stabilisation and disinflation in Peru and Uruguay (CPI Inflation, annual %)

Once inflation consolidated at single-digit level, financial systems began to progressively de-dollarise in terms of credit and deposits. Figure 7 shows that, since the early 2000s, Peru reduced the dollarisation of bank credit from 80% to 27% in 2022. In Uruguay, the dollarisation of credit fell from 70% to 50% by 2012, although it then stabilised. As for deposits, a gradual reduction is also observed: from 73% to 41% in Peru, and from 90% to 71% in Uruguay.

Figure 7. De-dollarisation in Peru and Uruguay

This indicates that de-dollarisation requires prolonged periods of stability and the sustained reconstruction of credibility in the national currency. Furthermore, it tends to stabilise at low but persistent levels. Even so, it is an inevitable consequence of price stability: economic agents tend to prefer a stable and liquid local currency for their everyday transactions, rather than a hard and more costly currency like the dollar, which is not issued by the Central Bank.

In other words, paradoxically, the success of the stabilisation plan in reducing inflation to low and stable levels will be an obstacle to achieving the Milei administration’s goal of fully dollarising the economy –and doing so endogenously–. The ‘law of gravity’ works in the opposite direction.

Conclusions

Given the high level of dollarisation in Argentina and the role of the exchange rate in price formation and inflation expectations, the exchange rate band appears to be a useful tool for transitioning towards a floating regime as the fiscal balance consolidates –as foreseen in the programme with the IMF– and the Central Bank (BCRA) gains credibility.

In the context of currency competition, where the dominant role of the dollar in price formation and the financial system is recognised de jure, the current monetary targeting regime will lose effectiveness, and the BCRA will need to intervene within the floating band, not only during the transition but especially when the system converges to a floating peso with inflation targets, as in Peru and Uruguay.

The main reason is that both with the monetary targeting of the transition and with an inflation targeting regime as the ultimate goal the interest rate as a tool will be insufficient to anchor expectations, and it will need to be complemented by occasional interventions in the foreign exchange market –to moderate fluctuations and prevent them from being passed on to prices– much more so than is necessary in non-dollarised economies.

Finally, although the government is actively promoting the use of the dollar, the reality is that if the stabilisation plan succeeds in consolidating a low and stable inflation rate –accompanied by exchange rate interventions that moderate price volatility– and gradually but steadily rebuilds confidence in the Argentine peso, full dollarisation will not only be unnecessary but also difficult to achieve. The cases of Peru and Uruguay, two dollarised countries that carried out successful stabilisation plans in the early 1990s, are illustrative: as inflation was consolidated at single-digit levels and credibility in the national currency gained ground, the economies gradually but slowly de-dollarised. The ‘law of gravity’ works in the opposite direction of the Milei administration’s goal of fully –and endogenously– dollarising the economy.

[1] The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the opinion of the Bank of Spain.

[2] The main exception to the lifting of the exchange controls refers to the inherited stocks of dividends and debt services with related entities, for which the Central Bank (BCRA) will issue a new series of Bonds for the Reconstruction of a Free Argentina (BOPREAL) denominated in dollars. These bonds may be purchased in pesos to meet obligations with foreign entities related to debts or dividends prior to 2025, and commercial debts with a date prior to December 12, 2023.

[3] For monitoring the targets of the agreement with the IMF, the program uses the evolution of the Central Bank’s net domestic assets (NDA) as an indicative target, rather than the transactional M2.

[4] The Central Bank (BCRA) may also choose to use other monetary control instruments, such as modifying regulations related to reserve requirements and the composition of minimum cash requirements.

[5] Amado, María Alejandra. Ongoing work on the transmission of US monetary policy in Latin American banking systems, 2025.

[6] The estimates are made using local projections (Jordá, 2005) for the transmission of domestic monetary policy and US Federal Reserve monetary policy to bank credit in Latin America. A panel of 140 banks operating in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru was used. It controls for domestic and US fundamentals (4 lags), credit behavior persistence (4 lags), as well as fixed effects at the bank and country levels, and bank characteristics. The sample period depends on the data availability for each country: for Peru, Brazil, and Mexico, from the first quarter of 2006; for Chile, from 2008; and for Colombia, from 2015; up to the last quarter of 2023. Monetary policy shocks are estimated as Taylor residuals. Shaded areas correspond to 95% confidence intervals.

[7] Pass-through: impact on inflation of a 1 percentage point change in the exchange rate.

[8] There is another reason why central banks in highly dollarised economies may want to limit exchange rate fluctuations, particularly sharp depreciations, as they lead to a revaluation of foreign currency-denominated debt expressed in domestic currency. This ‘balance sheet’ effect becomes problematic if borrowers are not hedged against exchange rate risk, either naturally as exporters whose income is in dollars, or through currency derivatives, which is uncommon given the underdevelopment of these markets in the region (See Alfaro et al., 2023 or Giraldo and Turner, 2022).