Summary[1]

The New German government under Friedrich Merz faces three main challenges in its relations with the US: (a) the trade war and Germany’s economic performance; (b) the role Germany can play in US-brokered Ukraine ceasefire negotiations and its continued support for Ukraine; and (c) the future of European defence, potentially without the US. All three policy challenges are unprecedented in Germany’s post-1945 history and will require a rethink of Germany’s role in Europe and in transatlantic relations.

It remains to be seen whether Friedrich Merz’s traditional free-market recipes for the German economy will be sufficient at a time when geopolitics are dominating and largely defining the economic performance of transatlantic partners.

Key takeaways

- In the tariff and trade war with the US, Germany is particularly vulnerable due to its years of zero economic growth and its major trade deficit with the US; however, it should not lose sight of the economic challenge posed by China.

- On Ukraine and Russia, Germany will act in a quad with the UK, France and Poland to keep the US engaged in Ukraine and to place the blame for any failure on Russia instead of Ukraine. However, Germany does not see itself in a military leadership role in a reassurance force.

- On the risk of a US withdrawal from Europe, Germany tries to bolster its conventional capabilities while at the same time relying on an enhanced UK and French nuclear presence. Berlin sees a responsibility for itself in helping to strengthen deterrence in Eastern Europe.

Throughout Germany’s post-1945 history, rarely has there been a more challenging time for a German chancellor to navigate the country’s future. The pillars of German foreign policy –transatlanticism, Western integration– are under question with the second presidency of Donald Trump and, at the same time, Europe is a far cry from the defence readiness it exhibited during the Cold War, while Russia reconstitutes its military with China’s help at a rapid pace and continues to be a threat to Ukraine and also to Europe. Likewise, Germany’s economic competitiveness is suffering not only from the trade and tariff war with the US, but much more so from its long-standing reliance on China as an economic growth factor. Now, China’s export overcapacity has made Beijing the ‘export world master’, and Germany’s industry is suffering from cheap, state-subsidised competition. How will the new German coalition –bringing together the two main centrist parties, the Social-Democrats and the Conservatives under Merkel’s successor (and longtime arch-enemy) Friedrich Merz– address these challenges? Especially, as centrist parties in Germany have lost a significant share of the vote to the radical right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD), and can thus not muster a two-thirds majority without left- or right-wing populists? Three policy issues will put Germany in the midst of the transatlantic tension with the US: the trade and tariffs war, the US attempt at negotiating a ceasefire between Ukraine and Russia, and the risk of an end to US security guarantees in Europe.

The trade and tariffs war

For a long time, as Constanze Stelzenmueller has put it, Germany’s economic model could be summarised by: (a) outsourcing security to the US; (b) outsourcing economic growth to China; and (c) outsourcing energy needs to Russia. This model, based on an export-led economy, has rapidly changed since 2022. Before Donald Trump came into office, Germany had become dependent in all three areas on the US: for its energy needs, its security and its economic growth, with the US overtaking China as Germany’s main trading partner. While the reliance on the US made many Germans more comfortable than a reliance on Russia or China, the return of Donald Trump has thrown the relationship into instability. The US President has pursued a radically protectionist agenda, focused squarely on reducing trade imbalance with a disruptive approach in disregard of many economic disadvantages. The US President has also not shied away from a trade and tariffs war with the EU. Although protected by the EU, within the Union, Germany has been particularly vulnerable to US pressure. Together with Mexico, Vietnam and China, Germany belongs to the four countries with which the US has the greatest trade deficit. Although it can use the European Commission and its mandate for trade negotiations as a buffer in direct conversations with the US, tariffs and economic uncertainty are further hurting a German economy that has not seen economic growth since pre-pandemic times and is the least-growing economy in the EU. Much of this goes back to not only the pandemic but to a long-term reliance on the Chinese market and exports as a growth engine for Germany. Only belatedly have German companies and politicians realised that China’s economic model, absorbing others’ exports, has changed to itself exporting high-technology goods. The new German government under Friedrich Merz has taken a rather traditional approach to stimulating the economy: reducing tax burdens on companies and removing bureaucratic red tape and climate-related regulations, which reflects a traditional liberal approach to reinvigorating the economy, in contrast to the EU-wide approach dominated by the Draghi report and the European Commission/Paris’ approach of more state intervention, subsidies and joint debt to make the EU industrially competitive. It remains to be seen whether Friedrich Merz’s traditional free-market recipes for the German economy will be sufficient at a time when geopolitics are dominating and largely defining the economic performance of transatlantic partners.

Ceasefire negotiations

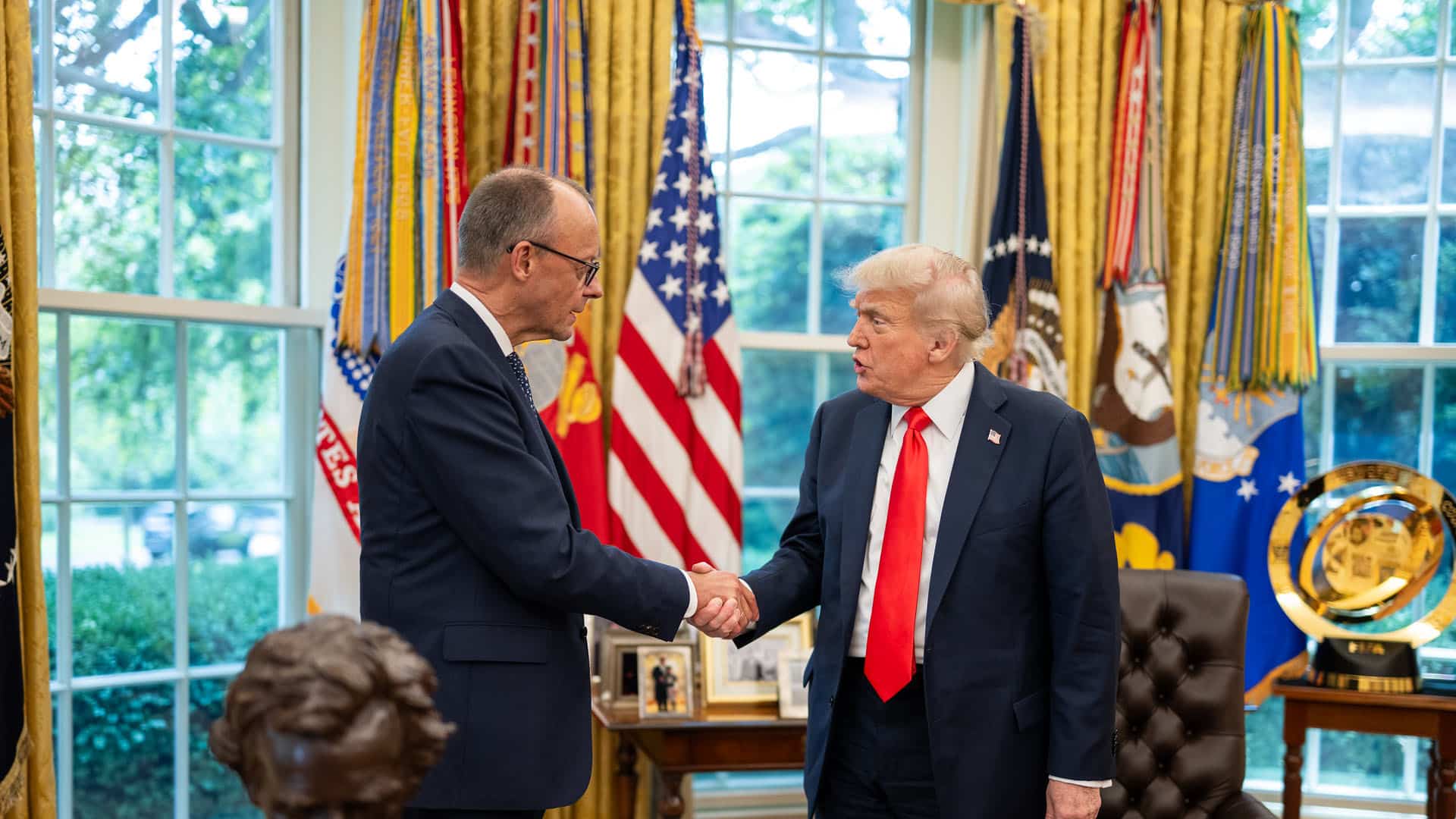

The new German government, together with France, the UK and Poland, will also have to play a major role in making sure that any US attempt at a ceasefire in Ukraine is not to the latter’s disadvantage. Here, Friedrich Merz’s sees himself in position where he tries cooperatively with other European partners to shape the direction of Donald Trump’s thinking, and to convince him that further pressure on Russia, not Ukraine, is necessary, and that the former, and not the latter, is the problem in negotiations. This was also his main talking point during his Oval Office visit to see Donald Trump. Although Merz himself has been much more outspoken on support for Ukraine during his time in opposition, for example about delivering Germany’s long-range Taurus missile, he has now become more cautious in office. Germany is supporting Ukraine’s homegrown capabilities for long-range strikes instead, and Chancellor Merz has also not committed the country to any military participation in a European reassurance force for Ukraine. While it is unlikely that Germany could entirely excuse itself from such an effort, it demonstrates that despite its increase in defence spending, Germany does not see itself in a military leadership role in Europe, but in a cooperative quad with France, the UK and Poland. This will also be the likely format to address any challenges related to a potential end of US security guarantees in Europe.

A (potential end of the) US role in Europe

The new German government and its Chancellor Friedrich Merz pursue a two-pronged strategy in dealing with the risk of a potential end of US security guarantees in Europe: (a) buy time and keep the US engaged; and (b) build up European defence capabilities but keep the door open to the US (ie, no ‘European strategic autonomy’ that seeks to fully decouple from the US). Berlin considers the most likely scenario a reduction of the conventional US presence in Europe, while the nuclear umbrella remains intact. The US could withdraw the additional 20,000 troops placed in Europe after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 or even go beyond that number. These troop withdrawals could also affect Eastern Europe and the presence of NATO deterrence forces there, established after 2014. The US force posture review will give more clarity, but there is no reason to be naive: the Pentagon is dominated by Euro-sceptics who would like to withdraw significantly from Europe and to relocate to the Indo-Pacific. While lawmakers on the Hill try to counter such thinking, it remains a serious possibility. The US ambassador at NATO, Matthew Whitaker, has repeatedly stated that there will be a phased approach of US troop withdrawals that should leave no ‘strategic gaps’, but how exactly this will look remains uncertain. The US could also decide to move the nuclear weapons stationed in Germany to Poland, which has asked for it.

For Germany, a reduction of US conventional presence would pose two problems.

First, if that reduction includes Eastern Europe, how to replace the US conventional troop presence in Eastern Europe credibly? Germany is the lead nation in Lithuania and has just promised to station a brigade there as a deterrent. However, it already has major problems in mobilising a brigade and the necessary equipment. Going beyond a brigade presence, for instance for other Baltic states, would be a significant strain on the German army. And, ultimately, a German troop presence has less deterrence value in Russian eyes than a US troop presence, which might require thinking about even larger numbers.

Secondly, if the US reduces its conventional troop presence, how credible will its nuclear umbrella still be? This is a question that European politicians, such as Helmut Schmidt, were constantly occupied with during Cold War times: how to convince Moscow that in the event of an attack on a European ally, the US would actually risk one of its own cities in a nuclear exchange for the defence its ally? The solution was and always has been that a US conventional troop presence increases credibility, since a US soldier harmed by an aggression would always be followed by a US response. Furthermore, would a US troop withdrawal, even if coordinated with European allies, be perceived by Moscow and Beijing as a green light for their own spheres of influence?

The approach of the new German government is to uphold US credibility at all costs. Immediately after his election, Friedrich Merz openly talked about the need to become independent from the US. Such talk has completely disappeared. The strategy now is to not question the US commitment to Europe publicly, to keep the US engaged as long as possible, to buy time until Europeans have built up their defence capabilities, and to hope that this will result in a stronger European pillar in a continuing US-led NATO, instead of a European NATO without the US. For that purpose, Germany has made the most significant step of finally using the fiscal flexibility that its debt brake has allowed for to invest massively in defence (everything beyond 1% of GDP on defence spending can be financed via debt now), a move that few other European countries can emulate. This basically means limitless defence spending and has made it easier for Germany to agree to the 5% target that Donald Trump demanded (in Mark Rutte’s version of 3,5% for direct defence spending and 1,5% for resilience, infrastructure, etc). With this move, Germany has not only taken away a major point of criticism from the Trump Administration –Germany’s lack of investment in its own defence– but also opened the door for significant European defence investments. This is just in time ahead of the NATO summit in The Hague at the end of June, where defence spending, but also the trade and tariffs war, and negotiations with Ukraine and Russia can come up and disrupt the summit in any imaginable way. It will be the first test if Germany’s strategy to deal with these interlinked transatlantic tensions will be successful.

[1] This text is based on a presentation for the workshop ‘The future of the transatlantic relation’ that took place on 8 April and was organised by the Prince of Asturias Chair at Georgetown University, the Elcano Royal Institute and FLAD.