Why do young European-Arab Muslims, and converts, go to join the Islamic State (ISIS or Daesh) to fight or sacrifice themselves, in Syria, Iraq and Libya, among other places, and, when they return, in Europe itself? It is essential to find out. The explanation frequently comes more from anthropology and psychology than security experts, who are increasingly incorporating such disciplines.

The summary that follows is taken from a range of sources, but principally from the research and writings of Scott Atran, an anthropologist who has carried out a great deal of fieldwork in the combat zone, has testified to the US Congress, is Research Director at the CNRS in Paris and Professor at the University of Oxford, and was recently in Madrid; and Nafeed Hamid, a cognitive science researcher and specialist in radicalisation and terrorism, who has co-written various highly interesting articles with Atran. A starting point, however, is that there is no single cause that can account for this complex phenomenon.

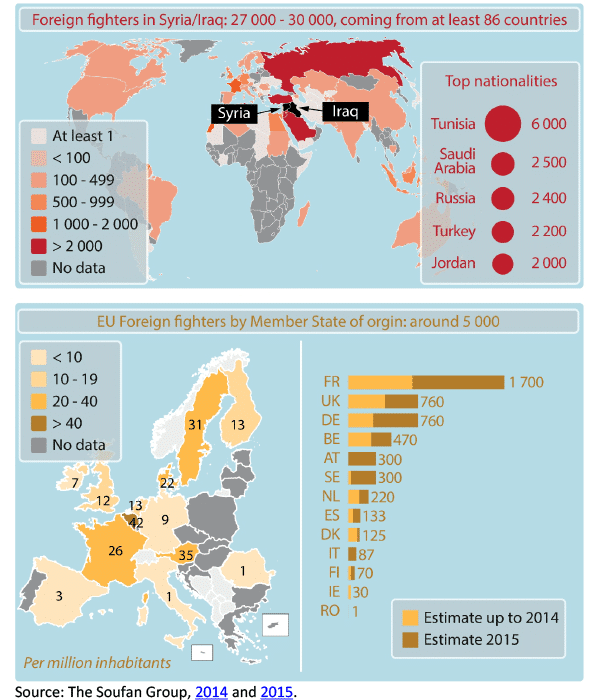

Numbers

Some 5,000-6,000 young people (others speak of 3,000) have left Europe, predominantly from France, Germany and the UK. This sounds like a lot in absolute terms, but in relative terms it is not. According to the French Prime Minister, Manuel Valls, it accounts for 0.03% of the Muslim population in France (0.14% in Belgium). The hubs of radicalisation vary: in some cases districts and prisons, as in France, or universities in the case of the UK.

Spiritual force

The indigenous ISIS fighters are significantly less brave than the foreigners, who exhibit more passion. As one of them says, ‘Better an end to the suffering inflicted by the status quo, with the hope of something better, whatever suffering and horror it takes’, which is an apocalyptic view to say the least. The ISIS fighters and terrorists have a ‘spiritual force’ (which is not the same as a religious force) that their enemies lack, and it drives them to make sacrifices. On the opposing side, only the Kurds, who have a conviction of their ‘Kurdishness’, and the much less numerous Yazidis, have a comparable force.

Frustration

Many feel marginalised. They feel neither Arab –they speak the language poorly– nor from the country of their parents or grandparents, nor the country where they live. They do not come from the middle classes, like the founders of al-Qaeda –made up mainly of engineers–. Although the recent arrest in Pinto (Madrid) of Aziz Zaghnane, a Moroccan marketing director and headhunter, accused of being a talent-spotter for ISIS and of organising a Jihadist recruitment cell, may indicate a change, at least in the elite. ISIS is redeploying its leaders in Europe with the greatest capacity for attracting new recruits. ISIS knows very well how to convert the feeling of unhappiness that arises from a sense of marginalisation into anger and subsequently into a thirst for revenge and violence. The thirst for vengeance is of great importance for ISIS.

Adventure and romanticism

The search for adventure, mixed with a certain romanticism and the idea of having a meaning in life is what sets these young people off.

Younger

They are getting progressively younger: teenagers and post-adolescents. The group that is growing fastest is aged between 11 and 17.

Money

This also motivates them. ISIS pays them little, but it pays.

Friends first

The network of friendships is the number one factor: 80% are recruited through groups of friends, whether physical or virtual on the Internet. Also significant in some cases are educational environments. The family, including of course the parents, count little, although in some networks the role of mothers is growing.

Sexual relations

For men, the promise that they will be given women, whether as wives or as mere sex slaves, is also an important factor for the youth who join ISIS to fight in the Middle East.

More women

The number of women joining ISIS is growing all the time. They account for one out of every eight fighters leaving Europe. They do so for the same reasons as men, as well as humanitarian reasons (they want to act as doctors, nurses, etc.). And they want to turn into soldiers, combatants, although on arriving they often find they are used for other purposes. They are essentially post-feminist and post-adolescent.

Religion is not the main factor

Jihadists do not usually have a profound religious training, nor are they regular mosque-goers. Many were not even believers prior to joining their networks, in which however they become a species of born-again Muslims, with a highly simplified and radical idea of Islam. And there are more and more converts of a non-Arabic and non-Muslim background (6% of Belgian fighters).

France is setting up Jihadist de-radicalisation centres. They are not easy or quick to get up and running, but more important would be to implement policies tackling the frustration of these young people, which provides the breeding ground for a minority of violent radicals. The election of the Labour candidate Sadiq Khan, the Muslim son of Pakistani immigrants, to the mayoralty of London, is a step in the right direction and a promising sign.