The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), an obscure but important body with headquarters in The Hague, did not enter into questions of sovereignty, but in the complaint lodged by the Philippines against China in 2013 it ruled in 501 densely-worded pages last week that Beijing’s claims to certain rocky outcrops in the South China Sea lacked any legal basis, and therefore do not provide any right to control the surrounding waters. The verdict will not have any practical consequences because China, which does not recognise the tribunal’s jurisdiction in the case, will not cease to act as it has been doing so far. But it strengthens, juridically at least, those who oppose Beijing’s attempts to control this important shipping route; and it could end up bringing the sides to the negotiating table.

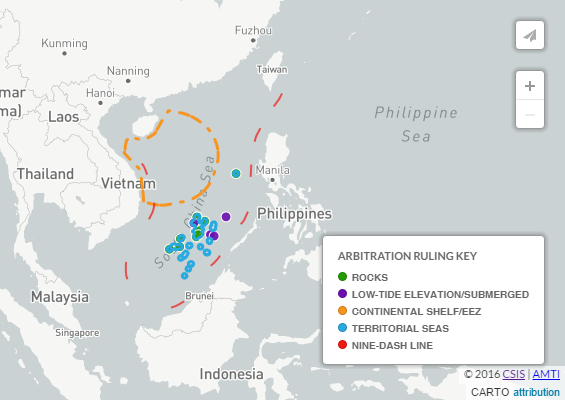

The court’s five judges did not go into the question of who has sovereignty over the outcrops, which include the Spratly Islands, the Paracel Islands, the Scarborough Shoal –over which Beijing has taken economic sanctions against Manila in recent months– and other atolls. These form a crucial part of the route towards the Malacca Strait, a sea lane of the utmost importance that plays a pivotal role in globalisation. The Court restricted itself to ruling on the implications of the outcrops for control of the surrounding waters, based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), signed in 1982 but in force only since 2008 and ratified by 167 States, including China. If the outcrops in question had been islands, they would have created a right to an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of 200 nautical miles and dominion over their resources (underground oil and gas, fishing, etc). If it is a question of rocks, outcrops and reefs incapable of sustaining human life and economic activity, such rights extend to only 12 nautical miles. And if the land only emerges at low tide, it does not confer any economic rights at all. In general, although not entirely, the Philippines retain the 200 nautical miles of the EEZ off its coast.

The geopolitics of the situation –an issue that the tribunal did not touch on– is even clearer in terms of the implications for maritime shipping than for undersea resources. 70% of the world’s seaborne trade passes through the region (and further afield, 80% of Japan’s trade and its essential supplies of oil and gas). Neighbouring countries –such as Malaysia, Brunei, Vietnam, Taiwan and Indonesia, and, further away, Japan– which are also embroiled in disputes of this kind with China, and with each other, have declared themselves satisfied with the ruling.

One factor that complicated the tribunal’s decision was that China –and other countries– had constructed artificial platforms on some of the outcrops in question. As well as rejecting Beijing’s claims, the judges find that China has done irreparable damage to the maritime environment by constructing in areas that are part of the Exclusive Economic Zone of the Philippines.

Although the Court has no practical means for enforcing its rulings –the UN Security Council, where China wields a veto, would need to take up the matter– the judgement may be seen as a victory for international law. Or perhaps not? China, which has claimed sovereignty over the region since 1949 when it first unveiled its famous ‘Nine-Dash Line’, enclosing 85% of the South China Sea, considers the verdict to be null and void. Although it has never specified what it wants to control within this line, it will continue with its policy of faits accomplis and military deployments, notwithstanding the fact that it may end up trying to negotiate with the Philippines. As Mario Esteban rightly points out, the PCA’s ruling also represents a major setback for Taiwan’s opposing claims to the South China Sea.

The US under Barack Obama (and Hillary Clinton when she was Secretary of State) deems it to be a matter of vital interest that no single power controls these waters. While there has been military tension between the US and China in the region, Washington has remained formally neutral; the Americans support the ruling, however, despite the fact that they never ratified the Convention on the Law of the Sea on which the judgement rests (they did however sign it, in 1994). Meanwhile Japan has a distinct but related dispute with Taiwan regarding the Okinotori coral atoll, not about sovereignty, which is accepted as Japanese, but about its characteristics and what these entail in terms of territorial waters and the Exclusive Economic Zone for Japan.

It is important to avoid military escalation. As a Brookings report points out, ‘in pushing back Chinese assertiveness’ in the area ‘the United States must be careful not to inadvertently contribute to the militarisation of the region’. Indeed the Obama Administration, despite its naval and aerial movements and manoeuvres, has warned against the militarisation of these disputes. The PCA’s ruling has already brought about increased tensions, even if they lead to some kind of negotiation. But the case also reveals the contempt China shows for international institutions when the latter do not fit its agenda (as, for that matter, the US showed in the context of Nicaragua in the 1980s at the International Court of Justice). For its part China is fully committed to its great project of geopolitical engineering –or ‘connectography’, to borrow Parag Khanna’s terminology–, namely the new Silk Road, otherwise known as ‘One Belt, One Road’. Traversing both land and sea, the project’s goal is precisely that of reducing China’s dependence on supplies and exports travelling via the South China Sea; a sea that, for the time being, it still seeks to control.