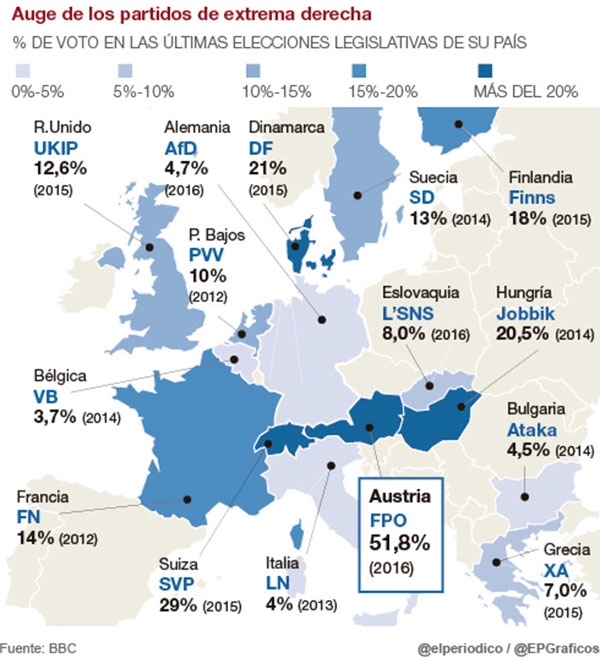

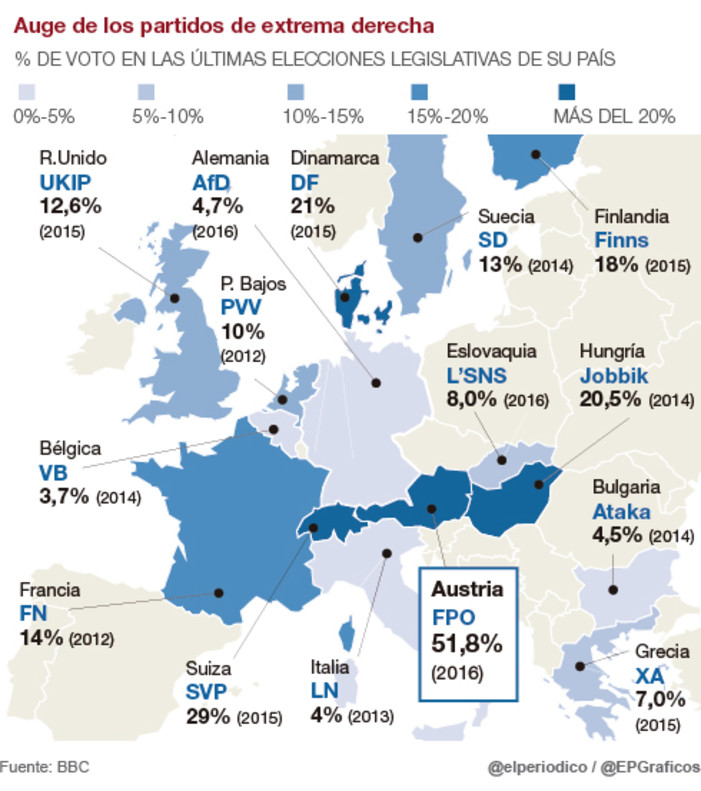

The so-called far right is currently present in most of the EU’s national parliaments, with the notable exceptions of Portugal, Spain, Ireland, Slovakia and the micro-states. It has also spread to some of the Union’s major partners in the rest of Europe, such as Serbia, Ukraine, Norway and Switzerland. What are the reasons for the swing to the right over the past five years in Europe, a continent characterised by its welfare models and shared democratic values? Rising migration often receives the most press coverage but behind the illiberal and xenophobic discourse flaunted by some, the most successful parties (Law and Justice [PiS] in Poland, the Freedom Party of Austria [FPÖ], Fidesz in Hungary or the French National Front of Marine Le Pen) are, in addition, putting forward ambitious economic plans based on subsidies to families and small businesses, and private-sector nationalisation programmes that are attracting the vote of what was the traditional left-wing electorate. The revival of the populist and radical right is therefore more than just the resurgence of racism: it represents a localism that seeks to challenge the current internationalist world order, the clash between sovereignty and globalisation.

Hence, in Poland, the PiS’s star policy during the elections was its support for families through amendments to the subsidy system, increases in parental leave and the future introduction of a zł500 (€113) monthly payment per child. In Hungary, Orbán and his populist party Fidesz have nationalised pension funds, taxed financial transactions and reduced utility bills to benefit homes and industries. However, the 0.8% GDP contraction in the last quarter, the decreasing quality of public services and the estimated high poverty levels (with 40% of Hungarians under risk of social exclusion) have propelled Jobbik, a party which is even more to the right than Fidesz, to become the country’s largest opposition party as it continues to push for increased government expenditure. In France, Marine Le Pen proposes increasing the minimum wage by 13%, tax cuts in utility bills and widespread economic protectionism. Finally, the Austrian FPÖ rejects free trade, with protectionist measures for national employees, and campaigns for more public housing and increased public expenditure on health services –thus garnering 86% of the blue-collar vote in the last presidential elections–.

The change in image and in the presentation of these movements is another key factor. The ‘official’ face of the PiS is Prime Minister Beata Szydło, a relatively unknown politician at the national level but whose moderate and conciliatory character is a great contrast to the abrasive style of the party’s founder, Jarosław Kaczyński. A similar contrast can be seen in the FPÖ, between the affable presidential candidate Norbert Hofer and its current leader, Heinz-Christian Strache. Meanwhile, in France’s National Front, Marine Le Pen expelled her father, Jean Marie Le Pen, from the party in 2015 adducing his numerous ‘faults’ and distancing herself from his anti-Semitic propensities. In addition to the new faces, a factor to consider is the calculated and superficial softening of these parties’ xenophobic discourses. Hence, they tend to publicly accept the right of asylum and the need for labour migration, praising ‘properly integrated’ migrants –thus initially and provisionally abstaining from criticising them as part of their rebranding strategy–. Their platforms claim to promote measures that, based on highly debatable criteria, will separate ‘real’ refugees from those seeking to exploit the welfare state, will restrict low-skill migrants and will introduce integration requirements based on cultural assimilation and knowledge of the national language. Finally, these parties tend to resort to economic arguments, such as the supposed reduction in wages due to downward pressure and the increase in public expenditure, thus transforming their xenophobic discourse into an appeal for protectionism that feeds on working-class disappointment and lack of job security.

The interconnection between markets and the prevailing economic frameworks, such as the Maastricht Treaty and the Eurozone, have contributed to give rise to a perception that Social-Democrats and Christian-Democrats essentially differ in their values and in the defence of certain rights than in their economic programmes. This perception’s hold on a large part of the electorate and the latter’s rejection of the austerity measures brought about by the economic recession, have caused a shift in voting preferences towards other more radical options, particularly penalising Social-Democratic parties. Hence, the rise in populist right-wing movements in Europe is not simply a reaction to the on-going migration crisis. It is, rather, a more generalised protest against globalisation by a part of the population that feels alienated from its benefits and that seeks solace from the return to sovereignty and the supposed protectionism that these parties claim to be able to provide.