A trend characteristic of our times, one that has been addressed before in this blog, is the hollowing out of the middle classes, globally and especially in the Western industrialised world. It applies particularly to the US where, as a proportion of the population, these classes have shrunk compared with 50 years ago. It explains major phenomena, from some of the problems with democracy, to protectionist tendencies and populist movements, especially those of the far right. Without this decline it would not have been possible to account for Trumpism and the partial shutdown of trade, especially with China. In the US, however, a twofold and significant phenomenon is unfolding that may be being replicated in Europe: together with the decline of the middle classes, the growth, in both number and wealth, of the high-income classes, something that creates a new type of inequality –it is not a matter simply of the super-rich– based fundamentally on the education received; and a swelling of the ranks of the lower classes. In other words, a polarisation of class sizes. In recent years the numbers who have not received a university qualification or its equivalent have fallen in the US, while those who have secured one have climbed the social ladder.

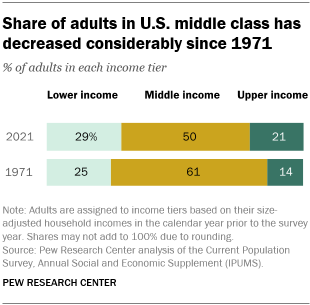

A recent study conducted by the Pew Center reports that the share of adults living in middle-class households in the US fell from 61% in 1971 to 50% in 2021, a fall of 11 percentage points in the last 50 years. This compares with an increase of seven percentage points in the higher-income classes, whose share rose from 14% to 21%. Those in the lower-income group rose from 25% to 29%. The phenomenon has been building for some time but accelerated with the fallout from the pandemic. The working, middle and upper-income classes all succumbed and emerged from the Great Recession, which began in 2008, at the same time, according to another Pew study. But the financial hardship attributable to the COVID-19 recession in the US was predominantly borne by low and middle-income families.

These trends over the past five decades do not mean impoverishment but rather increased inequality. Household income in the US grew considerably between 1970 and 2020 (by 50% in 2020 terms, with the median annual income rising to US$90,131). But it did so more in high-income families (69% and US$219,000) and less in low-income families (45% and US$29,963). And while blacks and Hispanics made progress, they made less than whites and Asians. The greatest gains, as already suggested, were made by graduates –underlining the role of education in social ascent and its absence in social decline– and those now aged over 65, the baby boomers. Inequality has nevertheless grown and persists between men and women.

Another study, from the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations and the Lester Brown Center on US Foreign Policy, reveals that these differences have political consequences. It is more likely that the 48% who describe themselves in this survey as belonging to the middle class identify themselves as Republicans than low- and high-income Americans, who tend to see themselves more as ‘liberals’, in the American sense, akin to ‘centre-left’. This is well understood by the Democrats, who in recent years have lost part of what used to be their ‘natural’ sociological base in this declining middle class.

To restore it, the current president, Joe Biden, advocates among other things ‘a foreign policy for the middle classes’, aimed at simultaneously addressing the challenges to the US both domestically and abroad; as far as protectionism and the policy towards China are concerned, some view this as Trumpism under a more moderate guise. The aforementioned survey suggests it is an approach that resonates and earns the support of the American public, acutely aware of the jobs and salaries that have been lost to China and other Asiatic countries. These voters are less interested than the administration in promoting human rights and democracy abroad, and much more in trade restrictions on China and industrial policies that benefit US companies. Policies to curb inflation –which has such a great impact on middle and low-income classes– are also a priority for governments, starting with Biden’s, European ones too. That said, there are doubts whether trade policy will work as a means of resolving US society’s problems of inequality.

None of this means the outright rejection of globalisation as such. A record number (68%) of Americans now consider that globalisation is generally good for the US, and almost three quarters that international trade is beneficial for US consumers, their own standard of living, for technology companies, the economy and agriculture. Clear majorities believe that improving public education (73%), strengthening democracy in the country (70%) and reducing racial (53%) and economic (50%) inequality are highly important for preserving US global influence. In other words, that the strength of the US starts at home. The majority of citizens believe that maintaining economic dominance (66%) and military superiority (57%) are key factors in US global influence.

These American trends towards a hollowing out of the middle classes are paralleled in the rest of the Western world, and have a certain causal relationship with the post-industrialisation and technology revolution that is under way. If the phenomenon persists it may lead to societies of thirds: one third high income, one third middle class, and one third low income, which will have, as in the US, its impact on the way democracy functions, something that has already been seen in recent years.

On a worldwide scale, there has also been a reduction in the global middle classes. The present author has been warning for some time of a possible clash of middle classes, between those in the developed world who do not want to fall back, and those in emerging economies who want to continue their ascent. It is a clash that may have been exacerbated by the uneven impact of the pandemic, and now the war in Ukraine, which in the Global South tends to be viewed as a conflict between great ex-colonial or imperial powers.

Image: White wooden houses in Chicago (US). Photo: Taylor Wilcox @taypaigey.