In their approach to bombing Syria, the different major powers are by no means pursuing the same strategic or political ends, or even justifying themselves on the same legal basis. The latest is Russia, which has been accused by the US of ‘throwing gasoline on the fire’. Although one of Russia’s targets, as of the rest, is Daesh –the self-styled Islamic State (IS)–, its first bombs have fallen on rebels fighting the regime of Bashar El Assad, to make it clear to all that it is there to preserve it. Of course, among the rebels there may be al-Qaeda militias and certainly the Russians have also attacked positions held by the IS.

The legal basis for bombing Syria varies according to who is involved, and partly reflects these different views. The Security Council has stated on several occasions, for instance in Resolution 2170 (2014), that the IS is a threat to international peace and security and called on UN Member States to take all appropriate domestic measures to counter it. Although it has never explicitly authorised the use of force, many legal experts do not consider it necessary. The international coalition –that also includes several Arab countries and Turkey– is acting at the request of the Iraqi government, which considers it is being attacked by the IS and has invoked the principle of ‘collective self-defence’ (art.51 of the UN Charter). The fact that it would also be necessary to bomb Daesh in Syria does not seem to be a problem to the coalition (although it has been for the British and French when the idea was first mooted, but is apparently no longer so) as it is a non-state actor and no-Syrian forces are under attack. In fact, the Assad regime has not protested too loudly about the issue.

The rejection of the use of force by the House of Commons in 2013 to penalise the Assad regime was a different case because it implied bombing Syria due to its use of chemical weapons against the rebels. It was the option Obama tried to promote and that he ultimately ruled out on account of the opposition of Russia, which managed to reach an agreement with Damascus for inspectors on the ground to remove any chemical weaponry. Cameron intention is to request a new vote in Parliament, but this rime for the UK to join the international coalition’s bombing campaign against the IS in Syria (as it is currently doing in Iraq). Times have changed and the refugee crisis is also a consideration.

France, which is also operating in Iraq, claims its actions are justified by ‘self-defence’, although now on an individual rather than collective basis. Its attacks against Daesh in Syria have come more than a year after the terrorist outrages in Paris for which it partly claimed responsibility, but admittedly only a short time after the recent failed attempt to blow up a high-speed train. Russia, which is not part of the international coalition, has the most solid legal basis for its action, as it is at the request of the ‘legitimate’ (a term used by Putin in his first speech in a decade at the UN General Assembly) Syrian government.

The goals pursued by Putin, who has regained the initiative on both the regional and world stages, are several. It is true that Daesh is a threat to everyone, including Russia and Iran. But in its struggle for power and influence with the US and Europe, Moscow also intends to make it clear that the West has not isolated it following its intervention in the Ukraine. It has approached Iran, which is also bombing Syria independently of the international coalition led by Washington. It is unclear what has been the result of the talks between Obama and Putin in New York, although, sensibly, at least the US and Russian military forces military and Russia are coordinating themselves to prevent potentially disastrous accidents. Meanwhile, the annexion of Crimea has already been forgotten, and fighting has temporarily ceased in the eastern Ukraine. Putin, Poroshenko, Merkel and Hollande gathered in Paris on Friday, 2 October, to strengthen the implementation of the agreements of Minsk that provide a greater autonomy to the pro-Russian region. Again, the truce has been a triumph for Putin.

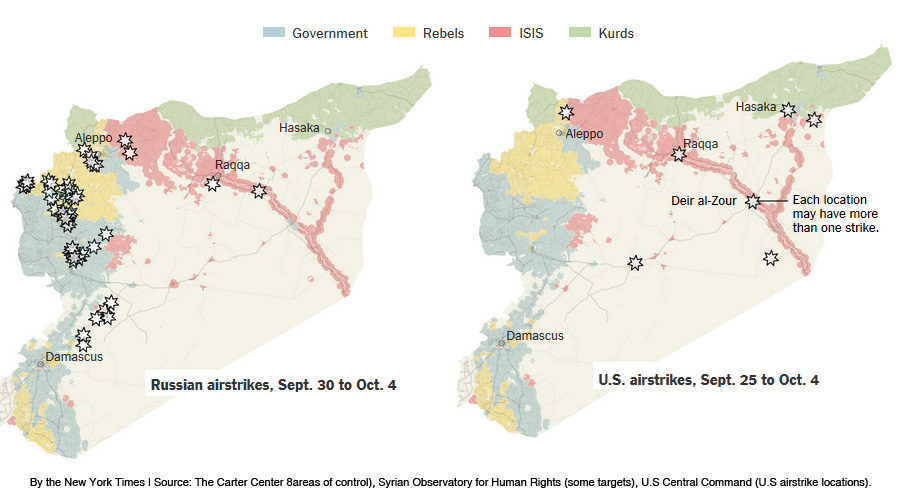

The West does not have not a single vision for Syria and the unfortunate US bombing attack on a hospital run by of Doctors Without Borders in Kunduz (Afghanistan) does little to help. There is agreement against Daesh, certainly, but not on the country’s future or on whether Assad is part of the problem or of the solution. In his speech at the UN, Obama made it clear that he wants both Daesh and the regime to go. They are part of the same equation. In this the British are in agreement. But Italy’s Matteo Renzi does not share that view. Neither do the French entirely agree, claiming –in the words of their head of diplomacy, Laurent Fabius– that ‘elements of the regime in Syria and of the moderate opposition are needed’ and that ‘it will be a failure to impose Assad on Syria’s future, and if he is required to excuse himself things will not progress’. That is, we must deal with the devil. The priority is first to finish off Daesh, or at least slowdown its progression, and then foster a national pact in Syria. In this the Spanish position is in agreement. And although it may not be ideal from a moral standpoint, it might be the only way out. Russia is filling a strategic vacuum. Dislodging El Assad is not in itself a strategy, as aptly commented by Richard Haass –an expert on the area and president of the Council on Foreign Relations in the US–. Regime collapse might lead the country to break up, even though it has already been split into three pieces: the one still controlled by the regime and the other two that are in rebel hands and occupied by Daesh. But how strong is the regime? To have had to ask for Russian help in addition to Iran’s indicates a certain degree of weakness.

Ultimately, no solution will be possible without Russian and Iranian cooperation and competition between Russia and the US will simply make a solution a more distant prospect. Meanwhile, that beguiling principle of having the ‘responsibility to protect’ seems to have been consigned to oblivion.