A host of studies report the growth of misinformation –from various sources– and fake news disseminated through social media and other means of transmission. But fewer focus on its real impact, something that could be less significant than supposed. Ultimately, Russian, Chinese and other bots may lead to a good deal of meddling and interference, but little in the way of real political influence. Their effectiveness may be less than is usually thought.

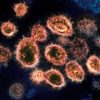

This is not to say that they are harmless. For instance, the rumour circulating to the effect that the spread of coronavirus is caused by the development of 5G mobile technology has led to the violent destruction of antennae in various parts of Ireland, the UK, the Netherlands, Germany and Cyprus. And although the idea could partly have been nurtured in the US, a recent Pew Center survey suggests that 30% of (predominantly youthful) Americans believe the virus was developed in a lab (somewhere or other), despite the lack of evidence to support such a theory. The same applies to a lesser extent in Europe. All this is part of the battle currently being waged to control the narrative, intensified in a year when the presidency of what is still the most powerful country in the world is again up for grabs.

In the 2016 presidential election, interference from Russian quarters –to the benefit of Donald Trump and the detriment of Hillary Clinton– was clear at various levels, and there are fears of a re-run of a similar operation in this crucial 2020. Stealing information from the Democrats’ campaign headquarters, using it and spreading fake news is one thing. But what is the actual level, the effectiveness, of this purported impact? A major study by Christopher A. Bail et al. on the impact of the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA) on the political attitudes and behaviour of Twitter users in the US comes to the conclusion that it was minimal, at least in terms of greater polarisation. This is despite the fact that users of the platform tend to live inside ‘echo chambers’ and have a high interest in politics. The IRA is extremely active. In 2016 alone it published more than 57,000 messages on Twitter, 2,400 on Facebook and 2,600 on Instagram. The study is based on 1,239 Twitter users, both Republicans and Democrats, at the end of 2017, combined with unpublished data about the IRA. In fact, only 11.3% of the participants in the study’s survey interacted directly with the Russian bots. Although the conclusions leave important questions about the impact of the Russian misinformation and manipulation campaign unresolved, this preliminary effort is the first major study of the problem.

A well-known earlier study published in 2018 in the journal Science, which analysed 126,000 rumours in English tweeted by 3 million users over the course of 10 years, concluded that ‘truth simply cannot compete with hoax and rumour’. As an article in The Atlantic put it, ‘falsehood consistently dominates the truth on Twitter… false rumours… penetrate deeper into the social network, and spread much faster than accurate stories’. However, another recent study concluded that fake news websites may not have a major effect on elections. In 2016, 44% of predominantly right-wing voters viewed at least one of these websites. Notwithstanding this, the same voters also accessed many legitimate news stories online.

If these studies are correct, it seems not only that bots are relatively insignificant when properly measured but that the same can also be said of fake news stories, broadly defined as ‘deliberately false or misleading information passed off as legitimate news’. A study by Duncan Watts et al. also points in this direction, firstly because, at least in the US information ecosystem, television dominates other media, including social media, in terms of news. Fake news comprises only about 1% of the general consumption of news and 0.15% of Americans’ daily media diet. Furthermore, news on its own accounts for a small fraction of media consumption, at least in the US. Consumers look for other things from the media.

By all events, the issue of the infodemic and its penetration reveals widespread insecurity in the West. There does not seem to be the same fear running the other way in Russia, or in China, which is still on the learning curve in this field of misinformation and operations of influence, as the Czech expert Ivana Karásková points out. The US, of course, has a President who has positioned himself as the misinformer-in-chief.