Like in the nineties, globalization has become, anew, a buzzword in political, sociological and economic debates. Moreover, it has been a major issue in two of the most important recent political campaigns in Western countries: the Brexit referendum and the US presidential elections.

An increasing number of analyses are now dealing with the magnitude and evolution of globalization –is the world too globalized? too little? is the world globalizing or de-globalizing?– and with its effects –is globalization a good or a bad thing?–.

This debate might prove confusing as there is not even a consensus on the concept and definition of globalization, nor, therefore, on how to measure it. In spite of this, several studies have tried to define and measure globalization –take, for instance, the KOF Globalization Index elaborated by ETH Zürich–.

The Elcano Global Presence Index is not exactly an index of globalization but its results might provide with some inputs for this debate. Global presence is the extent to which countries project themselves out of their borders in the economic, military or soft domains. It is currently calculated for 90 countries and can be tracked back to 1990. Therefore, the aggregated value of global presence for all countries rated by this index could be described as the foreign policy space.

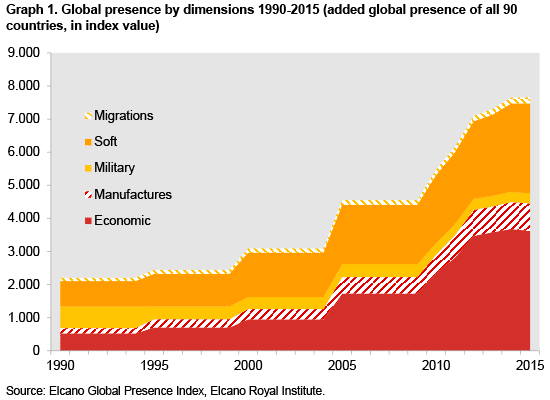

As pointed out in the latest edition of the Elcano Global Presence Report, after a period of rapid growth starting in the mid-2000s, since 2012, the rate of growth of such space has slowed down dramatically. And this indicates that there has actually been an intense process of globalization going on, particularly in the 2000s and first half of the 2010s, as ‘Brexeteers’ and ‘Trumpists’ point out. Aggregate global presence has increased by 3.5 times between 1990 and 2015, though at very different speeds over that period. Between 1990 and 2012, the average rate of growth was over 10%, but this fell to less than 2.7% for the 2012-2015 period. Moreover, it could be said that this foreign policy space almost stagnated in 2014 and that it only increased by 11 points in the last year (a 0.14% increase between 2014 and 2015 , Graph 1). In short, we have witnessed an intense process of internationalization that seems to slow down or even stagnate more recently.

Different dimensions have contributed to this trend to different extents. Economic presence has been the main driver of the expansion of total foreign policy space for these two and a half decades. The added value of economic presence of all countries was 6.5 times higher in 2015 compared to 1990; while in the case of soft presence it was just over 3 times higher, military presence has been cut by half. During the 1990-2012 period of rapid global presence growth, the economic dimension increased at an annual average rate of 23.7%; much faster than soft presence (8.6%) and coinciding with a decrease of aggregate military presence (-2.7%).

In short, globalization has been mainly, but not only, an economic process.

This can also be analysed by specific variables of global presence. Taking a closer look at trade in manufactures (within the economic dimension) and migration (part of the soft dimension) reveals that not only these two variables –often pointed out as the main drivers and threats of globalization– are only two of the multiple facets of the whole external projection of countries. Also, their weight is becoming less representative over time.

According to the Population Division of United Nations, the number of international migrants has increased 3.5 times during the last three decades and a half (from 94 to 243 million people). Trade of goods, that represented 29% of world GDP in 1980, now accounts for 45% of world GDP –despite the decline in recent years–; that is, it has multiplied by 17. So, yes, manufactures production has shifted to different countries, current account balances have opened and, despite the prevailing barriers, international migrants have increased in number.

However, what this presence index is telling us is that external projection and, therefore, globalization is about much more than these two variables. Manufactures represented 23% of total economic presence in 1990. This figure had decreased to less than 19% in 2015. Something similar happens with migration: 11% of soft presence in 1990 and only 6% in 2015. Meanwhile, new forms of global presence, such as digital exchanges, trade of services, financial interdependences, or development cooperation have appeared or increased and shaped the globalization process. Nevertheless, it is also true that not all the different components of globalization have the same impact and this also varies from one country (or even small community or particular sector) to another.

Recent political, social and economic events require re-opening the debate on globalization: its extent, its limits (if any), its causes and its consequences. However, in order to do so, a deep understanding of how the globalization process has transformed itself and what it has become is mandatory.