Theme: This analysis examines the debate in Spain on the European Union and its Constitution, in light of the referendum held on February 20.

Summary: After years of consensus on European issues in our country, the process of ratifying the European Constitution has revealed significant differences regarding the European Union. The new dissensus on Europe is visible in the three main points of the political debate: at the civic level, in the growing distance between the opinions and attitudes of the political class, on one hand, and citizens on the other; in terms of ideology, in the appearance of major tension between the left and the right, but also –and this is new– within the left and the right; and finally, at the territorial level, in the discrepancies over tactics and principles among old and new nationalist parties.

Analysis

Results

| National Voter Turnout | ||

| Total Voters | 14,204,663 mill | 42.32 % |

| Abstention | 19,359,017 mill | 57,.8 % |

| Nation Wide Results | ||

| YES | 10,804,464 | 76.73 % |

| NO | 2,428,409 | 17.24 % |

| Blank Vote | 849,093 | 6.03 % |

| Autonomous Communities with the highest percentage of NO votes | ||

| NO | YES | |

| Basque Country | 33,6 | 62,6 |

| Catalonia | 28,0 | 64,6 |

| Navarra | 29,2 | 65,3 |

| Turnout in other Votes | |

| European Constitution Referendum 2005 | 42.3 % |

| European Parliamentary Elections 2004 | 45.1 % |

| NATO Referendum 1986 | 59.4 % |

| 1978 Constitutional Referendum | 67.1 % |

The first divide: how to build Europe without Europeans?

Figure 1. Main indicators of Europeanism among Spaniards

Source: the author, based on Eurobarometer 61/2004.

Judging by the Eurobarometer data, Spaniards are still among the greatest Euro-enthusiasts on the continent. According to these data, Spaniards are among those who most support the integration process (69% in favour, that is, 22 points above the average, and significantly above some founding members, such as France, Italy, and Germany). We are also among those who most believe that we benefit from belonging to the EU (64% in Spain, versus 48% in the European Union). At the same time, there are few European countries which identify so strongly with Europe: the percentage of Spaniards who feel both European and Spanish (58%) is among the highest in Europe, once again well above the EU average.

The Europeanism of the Spanish political class seems clear beyond any doubt. Due to our history of isolation and exclusion, Spain lacks the anti-system, ‘Europhobic’ parties that in other countries have made ‘No to Europe’ a key part of their electoral platforms. Ironically, the Europeanism expressed by the Spanish people and their political parties is such that even ‘No’ supporters gather under the banner of ‘more Europe’, ‘a different Europe’, or ‘a better Europe’. Consequently, if we extrapolate the results of eventual parliamentary ratification of the European Constitution, based on the various political parties’ declared voting intentions, we find that the constitutional treaty would receive more than 94% support in the Spanish parliament (332 members would vote in favour of ratification of the European Constitution and only 18 would vote against). Considering that only 176 members of parliament are formally needed to ratify the European Constitution, we find ourselves before a seamless, nearly unanimous Europeanism that could easily surpass the highly qualified majorities required in Spain, for example, for constitutional reform (two thirds, or 234 members, for the special reform specified in article 168 of the 1978 Spanish Constitution).

Figure 2. Votes that the European Constitution would receive in the Spanish parliament

Votes in favour, 332 (94.8%): PSOE (164), PP (148), CiU (10); PNV (7), CC (3).

Votes against, 18 (5.2%): ERC (8), IU-IC (5), BNG (2), EA (1), CHA (1), Na-Bai (1).

Source: José Ignacio Torreblanca and Alicia Sorroza, Spanish Ratification Monitor, Elcano Royal Institute, Working Paper 8/2005, 3/II/2005.

Likewise, and contrary to other countries (in the Netherlands and in the Czech Republic, for example, the referendums have been called by opposition parties, against the explicit wishes of the minority governments), the referendum is supported unanimously in the Spanish parliament. Also, according to surveys (joint CIS/Elcano Barometer, December 2004), Spaniards broadly support the idea of a referendum (with 83% of citizens in favour and only 4% against).

However, despite the initial optimism that these statistics could generate, the results of the referendum confirm the emergence of the ‘political class/public opinion’ divide regarding European issues which polls where pointing at.

Table 1. Projected popular vote in the February 20 referendum

| October | October | November | December | January 4 | January 19 | |

| El Mundo | CIS | CIS | CIS/Elcano | Opina/SER | Opina/SER | |

| In favour | 36.5 | 37 | 45 | 42 | 36 | 45 |

| Against | 3.2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Spoiled ballot | 5.2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| Abstention | 12.4 | 12 | 14 | 10 | 14 | 11 |

| Undecided | 42.6 | 43 | 30 | 37 | 42 | 35 |

Source: José Ignacio Torreblanca and Alicia Sorroza, Spanish Ratification Monitor, Elcano Royal Institute, Working Paper 8/2005, 3/II/2005.

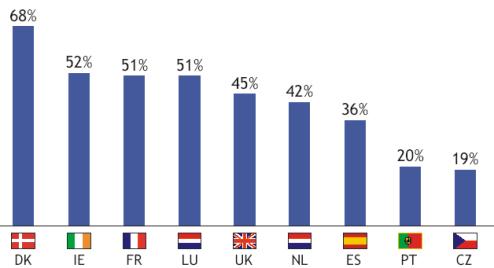

The degree to which people were informed has also been a relevant factor. In November 2004 (CIS/Elcano Barometer, December 2004), awareness of the European Constitution was extremely low: 84% of those surveyed said they knew little or nothing about it. As a result, there was a very large number of people who were undecided about whether they would participate in the referendum and about which way they would vote. The various surveys conducted throughout the autumn and before the official referendum campaign began show that participation in the February 20 referendum could easily be below 50%, given the number of people who are undecided or who have already decided not to vote. As shown in Figure 3, Spanish Europeanism contrasts with the lack of interest in actually voting.

Figure 3. Percentage of interviewees in the nine countries holding referendums who say they are ‘absolutely certain’ they will vote (Special Eurobarometer 214, 62.1/2005)

The second divide: ideological

To date, European policy in our country has been guided by consensus. Significantly, Spain was the only southern European country in which not a single vote was cast against joining the (then) EC, in the process of ratifying the Treaty of Accession in parliament. It is true that the Maastricht Treaty led to the first cracks in the Spanish left, especially in Izquierda Unida (IU) which was split between those who voted ‘Yes’ and those who abstained. However, on balance, this split was favourable to the Europeanists. Several high-profile figures in IU, who later went on to positions of responsibility in European policy –specifically, in negotiating the European Constitution– abandoned the left-wing coalition and joined the Socialist Party (PSOE).

Beyond the incipient debates on Europe as an economic venture and on the ‘social deficit’, the split between the left-wing parliamentary parties (represented by IU-IC) and the centre-left, represented by PSOE, may be old news. What is new is the fact that this split is extending to the main trade unions, who openly asked for a ‘Yes’ to the Constitution, while the anti-globalisation movements and other social movements were openly asking for a ‘No’, arguing that it is based on a neo-liberal economic model that is socially backward and subordinate to the United States.

Significantly, although IU-IC represent very little from a parliamentary perspective (five seats), nearly 28% of Spaniards agree with their argument that the European Constitution enshrines an economically-focused Europe and does not recognise the social Europe (CIS/Elcano Barometer, December 2004). For this reason, beyond the veracity of these arguments, which are sometimes quite strained, what is interesting is to consider the extent of this split in the left over the issue of Europe, what the long-term consequences of this will be, and especially, if this fracture will affect PSOE’s voters, limiting its possibilities of coming to broad agreements with the Popular Party (PP) on European policy.

If young people, who are better informed and better qualified, were to be become a major force in the Euro-sceptical left, this would indeed be a novelty. To date, studies of people’s identification with Europe have concluded nearly unanimously that Europeanism is directly related to the perceived benefits of belonging to the EU. For the younger and less qualified, the opportunities and benefits offered by European integration are potentially higher, making pro-European feeling more likely. By contrast, for the older and less qualified, the chances of being one of the ‘losers’ (in economic terms) of European integration is higher, and it is natural to expect more critical or even hostile attitudes from these sectors. If this should change, and young people become more sceptical or indifferent towards the integration process, this would truly be something new, since the younger generations have always been more pro-European than their elders.

Table 2. Government coalition and ratification of the Constitution

| Investiture | Constitution | ||||

| Yes | No | Abstention | Yes | No | |

| PSOE | 164 | 164 | |||

| ERC | 8 | 8 | |||

| IU | 5 | 5 | |||

| CC | 3 | 3 | |||

| BNG | 2 | 2 | |||

| CHA | 1 | 1 | |||

| PP | 148 | 148 | |||

| CIU | 10 | 10 | |||

| EAJ-PNV | 7 | 7 | |||

| EA | 1 | 1 | |||

| Na-Bai | 1 | 1 | |||

| Total | 183 | 148 | 19 | 332 | 18 |

Source: José Ignacio Torreblanca and Alicia Sorroza, Spanish Ratification Monitor,

Elcano Royal Institute, Working Paper 8/2005, 3/II/2005.

What is most significant and unusual about the current European debate in Spain is the fact that the coalition (PSOE, ERC, IU, CC, and CHA) with which the Socialist government is developing its legislative programme is not capable of presenting citizens with a united front when it comes to the European Constitution. In the general elections in March, and in the European elections in June, the PSOE made the European question in general and the Constitution in particular a key part of the collective project it wants for Spain. It is therefore understandable that many citizens are baffled by the disagreements within the governing coalition regarding the Constitution.

As Table 2 shows, of the 183 members of parliament who voted in favour of programme presented by the government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero at the time of its investiture in 2004, only 167 have announced that they will vote in favour of the ratification of the European Constitution. As a result, if the European Constitution were important enough to test parliament’s confidence in the government, then the government would lack the majority needed for parliament to ratify the constitutional treaty.

Considering the most significant criticisms made by Izquierda Unida, Esquerra Republicana and BNG, to the effect that the European Constitution subordinates Europe to the United States, destroys the Europe social model, criminalises immigration and smothers cultural diversity, it is significant that these parties and coalitions are able to consider their support of the government to be compatible with the latter’s supposed defence of policies so incompatible with their own core values and goals. Try though they may, the position of IU and ERC that this constitution is a step backward or in the wrong direction is not compatible with the government’s position that the European Constitution is a step forward. To minimise these differences by arguing that all members of the coalition that support the government share the idea of ‘more Europe’, once again means confusing citizens and robbing society of the opportunity for debate (which also happened when the Socialist party supported the candidature of Durão Barroso).

On the right, differences in opinion on the question of Europe are also evident. On the one hand, former president Aznar’s silence on the issue of supporting the European Constitution is extremely revealing, considering that his government was responsible for negotiating 447 of its 448 articles. However, two of the key issues on which the Aznar government disagreed with the new European Constitution –the reference to Christianity and the question of votes on the Council of Ministers– were not satisfied at the inter-governmental conference that closed the treaty, during the mandate of the current Socialist government, so it is no surprise that a large number of PP supporters are dissatisfied with the Constitutional Treaty.

Figure 4. Voting intentions based on the interviewee’s ideological position (percentages)

Source: Antonia María Ruiz Jiménez and Javier Noya, Los españoles ante el Tratado Constitucional y el proceso de integración europea, Elcano Royal Institue, Working Paper 62/2004, 10/XII/2004.

As Figure 4 shows, the farther voters are to the right on the political spectrum, the more likely they were to abstain from voting or to be indecisive about what to do on February 20. According to available data, nearly a quarter of Spaniards (23%) accept the message given out by the Partido Popular to the effect that Spain is losing relative weight with the European Constitution. Less than half (48%) of PP voters believe the European Constitution is good for Spain. This makes it fair to say that the fate of this referendum is in the hands of voters and sympathisers of the Partido Popular.

The third divide: the territorial issue

The visible discontent of nationalists with the European Constitution is easy to diagnose, but it is very difficult to predict where it will lead. For the ‘classic’ nationalists (PNV and CiU –historically and instinctively pro-European–), this constitution merited a qualified ‘Yes’. For the ‘new nationalists’ of Esquerra Republicana and Bloque Nacionalista, and also for the younger grassroots of the traditional nationalist parties, less ‘socialised’ in the culture of European policy, the European Constitution merited a ‘No’. As the internal dispute in Convergencia Democrática made clear, the generational factor appears to play a large role in this debate. Undoubtedly, the PNV is supporting a ‘Yes’ vote for strategic reasons that have much to do with the desire and need not to put the Ibarretxe Plan on a collision course with the European Constitution. However, beyond the idiosyncrasies of each party, there are more generic and broader reasons that explain the discontent nationalists feel towards European construction.

First of all, it is clear that this discontent is not exclusive to Spain. For some time now, regions with strong identities, unique political projects and legislative autonomy have been expressing their dissatisfaction with the insufficient institutional presence of regions in the European decision-making process. This is due to the merely consultative character of the Committee of Regions and to the de facto bleeding of powers that European construction has meant for many of them, as the European Union has absorbed a large number of law-making powers that were once in the hands of the regions, such as the environment, education and culture. This bleeding process, first detected in the early nineties by the German Länder, is the origin of the debate on subsidiarity. A decade later it remains unresolved.

To further complicate things, regions with legislative autonomy and great economic power, such as Bavaria and Catalonia, have witnessed in recent years how several small states (Slovakia, Croatia and the Baltic states) have received, or will soon receive, the full benefits of EU membership after openly choosing secessionist options, while some historically autonomous regions –despite their larger population, stronger identity and higher income– have fallen behind in terms of representation and participation in European policy making.

Secondly, for the nationalists, an unanticipated and undesired result of European integration has been the significant strengthening of the executive power of the states, through the transfer of powers to the supranational level. Many nationalists believed that European construction would involve a dual process in which states and governments would condense upward and downward, towards the EU and towards the regions. In fact, however, the governments of European states have acquired legislative powers in the EU which they previously lacked at the national level, as well as powers of coordination and negotiation that have given them an advantage on the domestic playing field. Those who hoped that the states would be diluted in a supranational sea, allowing the regions of Europe to emerge in a sea of multi-level governance, certainly have reason to be disappointed. Also, in the final analysis, the process of integration inevitably means a process of harmonisation, while most of the nationalist projects set out to establish differences. It is easy to proclaim the European slogan, ‘Unity in Diversity’, but it is difficult to put in practice, since practically any measure that can be adopted to strengthen nationalist projects (quotas, selective incentives and so on) will affect some established power or right at the European level (such as non-discrimination and domestic market issues), forcing the Commission or the competent EU institution to monitor these policies strictly.

Nationalist discontent with the European Union also has its roots within national borders. In Spain, despite the fact that our territorial structure resembles that of other federal states in Europe (Belgium, Germany and Austria), the internal organisation of the process of forming European policy is closer to that of more centralised states (France, Ireland and Denmark). This ‘federal blindness’ on the part of the Spanish state, as it has sometimes been called (see Martín y Pérez de Nanclares, Elcano Royal Institute, Working Paper 55/2004), is responsible in large part for nationalist discontent with the EU. Although it seems that the groundwork has recently been laid for a significant opening of European policy to the participation of the autonomous communities, as well as for satisfying the linguistic pretensions of these players, in Spain we are still far from finding a natural way to develop European policy based on horizontal cooperation among the autonomous communities and vertical cooperation between them and the government.

Figure 5. Intention to vote in Catalonia, the Basque Country, and the rest of Spain (percentages)

Source: Antonia María Ruiz Jiménez and Javier Noya, Los españoles ante el Tratado Constitucional y el proceso de integración europea, Elcano Royal Institute, Working Paper 62/2004, 10/XII/2004.

Given all the above, and as shown in Figure 5, there was considerably more intention to vote ‘No’ in Catalonia and the Basque Country than in the country as a whole, though the level is very low in absolute terms.

In the same way that the left is quite convinced that the European Constitution is socially insufficient, and the right is sure that Spain will lose relative weight in the EU, a significant number of nationalists share the opinion that the European Constitution does not recognise the identity of culturally distinct groups (20% of the national total, rising to 50% in nationalist circles). Given this structure of public opinion, once again, as occurred in the constitutional referendum of 1978 and in the referendum on NATO (which did not receive majority support either in the Basque Country or in Catalonia), the results on February 20 in Catalonia, the Basque Country and Navarra have been asymmetrical in terms of the rest of Spain. This would provide fodder for arguments positing the existence of separate realities with specific practical and symbolic needs that must be addressed in order to avoid paying a high price in terms of the legitimacy of the political system.

Conclusion

A campaign incomprehensible to citizens

This referendum campaign has been characterised by scarce discussion and exchange of arguments between the left and the right, and between the national and nationalist parties. This does not mean that there has been no debate. On the contrary, the debate has been very rich in the sense that it is forcing the left, the right and the nationalists to discuss their Europeanism and the compatibility of their respective European projects, and to stop being simply intuitively European. For the nationalists, for example, the debate has centred on how to defend their own identity in the constitutionally enlarged Europe. For the left, the problem resides in how to rebalance the economic Europe with the political and social Europe, without paralysing the Union or sending it spiralling into crisis. Finally, for the right, the debate seems to have focused not so much on how to Europeanise Spain, but on how to remain in Europe while at the same time maintaining the greatest decision-making capacity and autonomy.

However, these three debates do not mesh well with the logic of electoral competition among parties and it has proven difficult to articulate them around a ‘Yes’, ‘No’ or simple abstention. In fact, the messages that the political parties have been sending out to their supporters contained dissociations that may be incomprehensible, generating confusion. The Partido Popular, for example, has tended to argue ‘Yes’, based on the idea that the treaty is good for Europe, although not necessarily for Spain (‘it could be better for Spain’, is the term used by the PP’s Mariano Rajoy in its electoral message). The PSOE, meanwhile, has used the opposite argument (that Spain is doing well in Europe, even though we would like ‘more and better Europe’, nearly accepting that ‘other Europe’ referred to by the left). Finally, the nationalists appear to have taken a doubly negative stance: this model is neither good for us nor is it the Europe we want to see.

With all these intermeshed and confused strands, it is not strange that the campaign and debate on the referendum has been an odd one. Once again, as occurred in the last European elections, the left-right competition that citizens are used to, no longer has served to form their opinions and guide their votes when it comes to European issues. Europe appears to be the object of a strange dispute, impossible to fit into the terms of reference that citizens normally use. Prolonged exposure to these contradictions seems to be generating a permeating scepticism about European construction that we ought to observe with attention. An initial conclusion arising from this referendum is that, Spanish political parties must reconsider the coherency of their arguments and present these problems more openly to their supporters. As in France, where the internal debate in the right and the left is very intense, the political parties must continue talking to their voters about Europe, and must do so with better and more sophisticated arguments, if they hope to win their hearts and minds to the European cause.

José Ignacio Torreblanca

Senior Analyst, Elcano Royal Institute