Theme: The MFF 2014-20 has finally been agreed upon. Nevertheless, it is ‘perhaps nobody’s perfect budget but there’s a lot in it for everybody’.

Summary: The Multiannual Financial Framework is an extremely important tool for the EU’s long-term budgetary planning and stability. It determines the way in which the EU budget will be spent, to what political priorities it will be devoted and how it will be financed. The negotiations on the Multiannual Financial Framework 2014-20 (MFF 2014-20), which had reached a deadlock since the first attempt to reach an agreement in November 2012, were again placed on the agenda of the extraordinary European Council of 7-8 February 2013. After 26 hours of negotiations, the heads of state and government of the EU member states reached a political agreement on the maximum figures for EU-28 expenditure for 2014-20.[1] The EU Council’s President, Herman Van Rompuy, announced via Twitter: ‘Deal done! EU has agreed on MFF for the rest of the decade. Worth waiting for’. However, shortly afterwards he admitted that the MFF 2014-20 is ‘perhaps nobody’s perfect budget but there’s a lot in it for everybody’.

Analysis: The results of the negotiations on the Multiannual Financial Framework 2014-20 (MFF 2014-20) mirror the impact of the economic crisis on the budget. It was a long summit with numerous bilateral and trilateral meetings, several plenary sessions and breaks which reflected the difficulties in reaching a unanimous agreement between the 27 member states. Opinions about the European Council meeting’s outcome vary. While no head of government seemed to have lost face during the negotiation and all managed to sell the result at home as a victory, criticism and discontent have been voiced, most notably by the European Parliament.

In the context of budgetary constraints at the national level, the EU budget will shrink for the first time in its history over the period 2014-20. The overall level for commitments has been set at €960 billion, which is just 1% of the EU’s gross national income (GNI) and €15 billion less than in 2007-13.[2] This is clearly a triumph for the net contributors –also called the ‘Friends of better spending’–,[3] which since December 2010 had been demanding an EU budget in line with the austerity applied to national budgets and wanted to cap the budget at 1% of the EU’s GNI.

On the other hand, the ‘Friends of the Common Agricultural Policy’ (CAP) and the ‘Friends of Cohesion’ were also satisfied, since the resources for both headings were re-established after being sharply cut at the November summit. The agreement was a bitter disappointment, however, for the European Parliament and for all those who advocated an ambitious budget that would lead to an active stimulus to growth and job creation and to a stronger EU role in the world.

Nevertheless there are also positive signals. After the failed November summit and a negotiation process which started several years ago, the heads of state and government finally reached an agreement on this complex issue. Nothing would have been worse than failing in this important negotiation at a time of economic crisis in Europe. Within the characteristics of the negotiation process, in which the most reluctant actor sets the pace and the final outcome, it was clear that all participants would put their own national priorities forward and defend them firmly. That was the case, but at the end of the meeting all participants made concessions and accepted a compromise in order to have a new MFF and a budget for Europe. Furthermore, taking into account the structure of the EU budget which favours a ‘just return’ and the defence of acquired ‘budgetary rights’, there was really no chance for a revolutionary new EU budget. The main innovative proposals –related to new own-resources, that had been presented during the budgetary review and backed by the European Parliament– had already been blocked previously because of their sensitive nature concerning fiscal sovereignty. To conclude, the agreement is in line with the evolutionary character of the EU budget and the Council’s compromise on the new MFF 2014-20 reflects the willingness to revise the EU’s redistributive politics and a greater openness towards a debate on an institutional reform on resources.

Aside from this, the agreement was especially important for Spain. The fact that the country will remain a net beneficiary of the EU budget is a positive result. The Spanish negotiators managed to defend the country’s domestic preferences and improved on the results of the November Council, while the final agreement should have an indirect positive effect on the Spanish economy. Although the Spanish delegation was not necessarily to the forefront during the final negotiation, the Spanish Prime Minister, Mariano Rajoy, said that the EU budget for 2014-20 is ‘very good’ and the outcome was even beyond the expectations of both negotiators and analysts. According to first estimates by the European Commission, Spain will receive 0.2% of GDP as a global net balance throughout the period. Taking into account Spain’s growth forecasts, the figure could be around €15 billion for the seven years. This is particularly important considering that Spain’s two main sources of European funding (CAP and Cohesion policy) were subject to cuts in the current MFF 2007-13.

Table 1. Multiannual Financial Framework 2014-2020

| MFF 2007-14 adjusted for 2013[4] (€ mn, current prices) | MFF 2014-20 (€ mn, 2011[5] prices) | Variation (€ mn) | |

| 1a. Competitiveness for growth and employment | 90,203 | 125,614 | +35,411 |

| 1b. Cohesion for growth and employment | 348,415 | 325,149 | -11,159 |

| 2. Sustainable management and protection of natural resources | 412,611 | 373,179 | -39,432 |

| of which: market related expenditure and direct payments | 330,085 | 277,851 | -52,234 |

| 3. Citizenship, freedom, security and justice | 12,216 | 15,689 | +3,473 |

| 4. The EU as a global partner (excluding EDF and Emergency Aid) | 55,935 | 58,704 | +2,769 |

| 5. Administration | 55,535 | 61,629 | +6,094 |

| Total commitment appropriations | 975,777 | 959,988 | -15,789 |

| As a percentage of GNI | 1.12 | 1 | – |

Source: the authors.

This paper will attempt to explain the results of the Council negotiation, taking into account the results for Spain. We will argue that the positive results for Spain are made up of two main factors. On the one hand, Spain will contribute less to the EU budget than in the current period. On the other hand, the final agreement contains a series of extra expenditure which were not foreseen by former proposals.

The Spending Headings

Although no new proposals were tabled in the summit’s preparation, there seemed to be a changing trend in the perception of the EU’s needs. The EU cannot foster growth in the absence of some kind of investment and an increasing focus on youth unemployment. This concern emerged some weeks ahead of the Council. The EC had already proposed a youth employment package[6] in December 2012 and the topic had been raised by Van Rompuy during the summit’s preparation and by the French Prime Minister François Hollande in his speech to the European Parliament on 5 February. In fact, the MFF 2014-20’s main innovation is the creation of a specific fund to support the regions where youth unemployment is above 25%. A sum of €6 billion has been earmarked for this purpose, although only €3 billion will involve new funding. Aid measures amounting to €3 billion will be financed by the European Social Fund and another €3 billion will come from a new youth employment budget line.

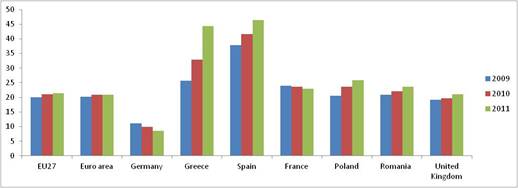

Figure 2. Youth unemployment in several EU Member States (%)

Source: Eurostat (2012).

Taking into account the Spanish labour market’s specific problems, Spain should –according to the government– receive €924 million directly from the new fund (a share of 30% of the fresh money). Additionally, in line with Spain’s demand to use the most recent data that reflect the effects of the crisis, eligibility and the number of unemployed workers concerned will be determined on the basis of 2012 figures. According to Eurostat all Spanish regions would have been eligible for the new fund based on 2011 data.

With regard to the spending headings, programmes under sub-heading 1a (Competitiveness for growth and jobs) are mainly focused on contributing to the fulfilment of the Europe 2020 Strategy (the promotion of research, innovation and technological development) and to the competitiveness of enterprises and SMEs. The returns from this sub-heading have been growing in Spain over the past few years. Spain could increase its share and, in the first four years of the 7th Framework Programme 2007-10, reach sixth place in the EU-27 in obtaining funds for R&D. During the period 2014-20 investment in research and development will primarily be based on excellence. However, in line with the Spanish preferences, the conclusions make specific reference to the synergies between Horizon 2020 and the structural funds in order to create a ‘stairway to excellence’ with the aim of enhancing regional R&I capacity and the ability of worse-performing and less-developed regions to create clusters of excellence. Although it is difficult to calculate the returns from this heading, spending on Heading 1a and the future Framework Programme Horizon 2020 will increase by 37% to €125.6 billion compared with the current MFF (€90 billion) and this could also imply increasing returns for Spain.

The ‘Connecting Europe Facility’ has become the real ‘balancing item’ under sub-heading 1a. The resources foreseen by the EC for this programme have been reduced from €41.2 billion to €29.3 billion. The sectors affected include transport (from €26.9 billion to €23.2 billion) and energy (from €7.1 billion to €5.1 billion) and telecom infrastructure (from the proposed €9.2 billion to €1 billion). Although the Spanish government strongly prefers the establishment of cross-border infrastructure projects, no assignation of funds to specific projects was specified. In addition, the project would have been managed by the EC in public-private partnerships, which actually would mean less direct funding from the EU budget. The impact is therefore not substantial.

As regards Cohesion Policy (sub-heading 1b), from being the leading beneficiary at around 25% of the total for the period 2000-06, in 2007-13 Spain will be overtaken by Poland and receive only 12% of total funds. This is still a good position, as Spain’s contribution to EU resources is less than 10%. In this respect, the Spanish government had a strong interest in maintaining overall spending in sub-heading 1b, ‘Economic, social and territorial cohesion’. Although the Cohesion Policy will be reduced by 3.5% from the current €348 billion, the European Council’s conclusions included a further €4 billion for Cohesion Policy for 2014-20 (compared with last November’s draft), bringing the total level of commitments for the heading 1b to €325.1 billion. The least-developed regions (including the Spanish region of Extremadura) would be the main beneficiaries of the final agreement. In general terms, investments in the EU’s Cohesion Policy will be distributed as follows:[7]

- A total of €164.8 billion for less developed regions (more than in the Commission’s proposal of €162.6 billion).

- A total of €31.7 billion for transition regions (less than in the Commission’s proposal of €39 billion).

- A total of €49.5 billion for more developed regions (less than in the Commission’s proposal of: €53.000 million).

- €66.4 billion for cohesion fund beneficiary states.

Several so-called ‘adjustments’ or ‘gifts’ were assigned under this heading to different countries in order to contribute to the final agreement. The ‘Spanish envelope’ for regions particularly affected by the economic crisis was reduced from an additional €2.75 billion (as proposed in November) to €1.8 billion, but the reduction was offset by additional funding for the Youth Unemployment Initiative. The envelope’s breakdown is as follows: €500 million for Extremadura, €624 million for the Spanish transition regions (Andalucía, Murcia, Galicia and Castilla-La Mancha) and €700 million for the remaining regions. The Spanish government’s traditional demands for a specific treatment within the Cohesion Policy for the Canary Islands as an ultra-peripheral region and for Ceuta and Melilla as remote border towns have also been fulfilled. The Spanish territories across the Mediterranean, Ceuta and Melilla, will continue to receive an extra €50 million. An envelope of €1.4 billion –the same amount as in November– is foreseen for the outermost regions, which include the Canary Islands.

With regard to the specific level of allocations to each member state, the conclusion pays special attention to regions affected by unemployment, which may be seen as a further concession to Spanish demands. In this respect, the regions exceeding the average unemployment rate of all the EU less developed/transition regions will receive an additional €1,300 (less developed regions) and €1,100 (transition regions) per unemployed person (above the average) per year. This change should imply an additional €930 million for Spain.

With regard to the safety nets for transition regions, Spain’s demands have been partially met. The Spanish government demanded fair gradual exit strategies for regions which are leaving the Convergence Objective in order to avoid abrupt changes in the funding received. According to the final agreement all Spanish regions whose per capita GDP for 2007-13 was less than 75% of the EU-25 average, but whose per capita GDP is above 75% of the EU-27 average during 2014-20, will receive the minimum level of support of 60% of their former allocation, 6% less than the Commission’s proposal in June 2011.

As a counterpart to these positive results, the Spanish government could not prevent the inclusion of a macro-economic conditionality clause which for the next framework establishes a close link between Cohesion Policy and the Union’s economic governance. This will mean that receiving Structural Funds will be conditional on fulfilling the commitments of the Stability Pact, the European Stability Fund and the procedure on excessive macroeconomic imbalances.

Spain is the second-largest recipient of CAP funds after France in the MFF 2007-13 and receives nearly €7.5 billion per year from this budget heading. Commitment appropriations for heading 2, ‘Sustainable growth: Natural resources’, which covers agriculture, rural development and fisheries, increased slightly with regard to last November’s proposal, from €372.2 billion to €373.18 billion, although they continue to decline compared with the current MFF. Of this amount, €277.85 billion will be allocated to market-related expenditure and direct payments. The rural development budget will be €84.94 billion. Compared with the current MFF, agricultural expenditure has been reduced by an average 11%, reflecting the budget’s updating.

Nevertheless, for the Spanish Agricultural sector, which is facing particular structural challenges, the agreement maintains an additional investment of €500 million for rural development. A new reserve will also be included under heading 2, with €2.8 billion allocated to support major crises affecting agricultural production or distribution. In line with the Spanish government’s demands, member states will also have a greater flexibility to distribute amounts (15% of the total) between both pillars of the CAP, which could increase the direct payments available to Spanish farmers.

One ‘victim’ of the negotiation has been heading 3, ‘Security and citizenship’, which has been cut to €15.7 billion, compared with €16.7 billion in the previous proposal, although there is a small improvement with regard to the current MFF. The Spanish government had demanded more financial resources for a common security and defence policy, as well as for police and judicial cooperation (specifically Frontex and Eurojust). Its demand has been met and, in addition, spending on heading 3 will have a special focus on insular societies that face disproportional migration challenges.

A further victim is heading 4, Global Europe, which was reduced from €60.67 billion to €58.70 billion during the Council negotiations. But the final agreement on this heading is also an improvement with regard to the current MFF. Although all member states benefit from spending on this heading it is not considered in the calculation of the national net balances. This is also true for heading 5, ‘Administration’, which has been cut from €62.63 billion to €61.63 billion. Nevertheless, compared with the current MFF, administrative expenditure will rise by 9.1% due to increases in pensions and the creation of a new European External Action Service.

These last cuts imply a saving of resources for Spain and have a positive impact on the net budgetary balance.

Revenue

Although there have been no important changes on the revenue side of the EU budget, the final agreement contains a commitment that the European Council will continue to work on the Commission’s proposal for a new own-resource based on value-added tax. Furthermore, a debate will be launched to examine if the Financial Transaction can become the basis for a new own-resource for the EU budget for at least some member states. One of the negotiation’s important results was that Spain will contribute less to the EU budget than in the current period.[8] This lower contribution is due to three factors: (1) the EU budget is lower; (2) some countries’ rebates or ‘cheques’ have been cut slightly[9] –although the UK’s rebate remains unchanged and Germany and Denmark will receive a new annual rebate of €130 million, the Netherlands’ €1.15 billion rebate is reduced to €695 million and Sweden’s €325 million has been cut to €160 million, while Austria will benefit from a gross reduction in its GNI contribution of €30 million in 2014, €20 million in 2015 and €10 million in 2016–; (3) there is an increase in the percentage member states can receive as compensation for the collection of Traditional Own Resources.

The review after two years (2016) will help to determine whether the budget needs to be adjusted.[10] In this respect, member-state contributions based on GNI could be revised to take into account more updated economic figures. This could also benefit Spain which is in the middle of a deep economic crisis.

Conclusions: The EU –soon to comprise 28 members– will have an austerity MFF up until 2020. Nevertheless, the political agreement on the MFF 2014-20 reached by the European Council on 8 February can be considered to be positive for Spain. First analyses indicate that Spain will remain a net beneficiary throughout the period. The Spanish negotiators defended their national preferences and improved the results of the November Council in several issues. The Spanish government has been in favour of giving more importance to unemployment criteria (especially youth unemployment) and to additional criteria such as the technology gap in the future Cohesion and R+D policies, as well as defending a strong CAP budget. Although Spain will have moderate gains from the EU budget, compared with the MFF 2014-20 the main objectives may be reached in a very difficult context.

This MFF is a crisis budget and this is the first time it has been reduced. Nevertheless, there have been some other novelties. Although the major part of EU investments in 2014-20 will be in the ‘historical’ spending areas –agriculture and cohesion policies–, they will both undergo significant cuts, while funding for the heading ‘growth and jobs’ –including research, infrastructure investment and education– will receive a significant boost. This follows a long-term trend of moving away from the more traditional spending areas towards horizontal issues. Furthermore, the increasing percentage of resources earmarked for specific policy objectives also fosters a paradigm shift from a redistributive-budget towards a governance budget. Moreover, other innovations include: alternative financial instruments, an enhanced role for the European Investment Bank, macroeconomic conditionality and an increased flexibility to use unspent resources in other headings.

Besides these modifications and innovations, what is disappointing is what has happened since the budgetary review started in 2007. In addition to its role in offering budgetary stability, the MFF also has a symbolic function: a larger budget would have sent an important political message. The creation of the fund dedicated to address youth unemployment will have to try to offset the clear failure in meeting the public opinion expectations and the objectives considered by the Commission and European Parliament in their initial documents. The MFF 2014-20 has been agreed upon, and this is good, but it will not be a strong instrument to tackle the crisis.

The European Council states at the beginning of its conclusions: ‘Looking to the future, the next MFF must ensure that the European Union’s budget is geared to lifting Europe out of the crisis. The European Union’s budget must be a catalyst for growth and jobs across Europe, notably by leveraging productive and human capital investments’. However, the final agreement failed to match its words with deeds. Considering the increased responsibilities at the EU level introduced by the Lisbon Treaty, the question is if all the EU’s policy objectives for the next seven years can possibly be met by this crisis budget.

Mario Kölling

Centre of Political and Constitutional Studies

Cristina Serrano Leal

PhD in Economics and Economic and Trade Counsellor (Técnico Comercial y Economista del Estado)

[1] European Council Conclusions, Brussels, 8/II/2013.

[2] COM(2012) 184 final, Brussels, 20/IV/2012.

[3] The signers of the Friends of the Better Spending Non-paper were Austria, Germany, Finland, France, Italy, the Netherlands and Sweden.

[4] COM(2012) 184 final, Brussels, 20/IV/2012.

[5] European Council Conclusions, Brussels, 8/II/2013.

[6] http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=89&newsId=1731.

[7] With three types of regions, defined on the basis of how their per capita GDPs –measured in purchasing power parities and calculated on the basis of Union figures for 2007-09– relate to the EU-27’s average GDP for the same period: (a) less developed regions, whose per capita GDP is less than 75 % of the EU-27’s average GDP; (b) transition regions, whose per capita GDP is between 75% and 90% of the EU-27’s average GDP; and (c) more developed regions, whose per capita GDP is over 90% of the average EU-27 GDP.

[8] According to Mariano Rajoy, this would mean additional savings of €3.3 billion.

[9] ‘Rajoy arranca 15.000 millones al presupuesto comunitario 2014-2020’, Expansión, 9/II/2013.

[10] Fabian Zuleeg, ‘The EU Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF): Agreement but at a Price’, European Policy Centre, 11/II/2013.