Original version in Spanish: Elecciones marroquíes de 2021: una nueva arquitectura política para un nuevo modelo de desarrollo.

Theme

The National Rally of Independents (RNI) party won a threefold victory in the parliamentary, municipal and regional elections held in Morocco on 8 September 2021.

Summary

Aziz Akhannouch, an increasingly prominent figure since 2016, who has been Agriculture Minister since 2007 and a key figure in the last three legislatures, secured victory for his party, the National Rally of Independents (RNI), in the parliamentary, municipal and regional elections held simultaneously in Morocco at the beginning of September. His comfortable win heralds a new political architecture that will govern the country over the course of the next legislative term and should lay the foundations of the ‘new development model’ the country has announced for the period leading up to 2035. This threefold election revealed the collapse of the Islamist Justice and Development Party (PJD), which had led the government over the previous two legislative terms and paid a heavy price for its subordination to the establishment, known in Morocco as the makhzen.

Analysis

With an almost mathematical regularity, as in every other five-year period, 8 September 2021 saw the holding of the fifth legislative elections during the reign of Mohammed VI. Such chronological regularity was absent from the long reign of his father, where states of emergency, coups d’etat, uncertainties over the relationship between power and the opposition, constitutional reforms and various interventions using the pretext of the Sahara issue imbued Hassan II’s Morocco with political instability.

The stability that may derive from such electoral regularity cannot hide the fact that the role played by elections in the country’s political development is relatively minor, given that the overarching guidelines of Moroccan politics emanate from the royal palace. These guidelines are set out, as in the days of his father, in the speeches the King gives on specific occasions each year: the opening of parliament in October, Throne Day at the end of July and the Revolution of the King and the People Day, held every August to commemorate the anniversary of his grandfather’s return from exile.

Justifiably, and with no little political realism, the leader of the Istiqlal Party, Abbas El Fassi, who led the government from 2007 to 2011, went as far as to say that his governing programme was that of His Majesty the King. The most recent example took place in October 2018 when Mohammed VI appointed an ad hoc extra-governmental commission to draw up a ‘new development model’ for the country. In April 2021 the commission submitted its general report,1 which will undoubtedly form the basis of the economic programme of the government that emerges from the recent elections.

Since the legislative elections of 2002, the first after Mohammed VI acceded to the throne, votes have been conducted with a degree of fairness and a wide margin of freedom, characterised by competitive electoral campaigns that lack the meddling of the administration and the spectre of ballot-rigging and falsification that always haunted the reign of Hassan II. They serve as a means of identifying the party whose task it will be to organise a coalition with a stable majority, albeit under the constant supervision of the Royal Council (also known as the ‘shadow government’, formed by the most influential royal advisors). In 2016 these advisors did everything possible to impose the most expedient candidate of the victorious party –dooming attempts by the charismatic Islamist leader Abdelillah Benkirane to form a government– as well as identifying the parties that he should include in his coalition. They also appoint technocrats unconnected to the parties but close to the royal palace, sometimes camouflaged under the initials of one of the so-called ‘administrative parties’, to key posts in government ministries and areas decisive to the country’s development.

A result announced in advance

It may be argued that the outcome of the 2021 elections, with the overwhelming triumph of the National Rally of Independents (RNI), was a foregone conclusion from the moment of the Justice and Development Party’s (PJD) second victory in 2016 and the failure of the Authenticity and Modernity Party (PAM), which had been the administration’s favourites to unseat the Islamists. The figure of Aziz Akhannouch, the Minister of Agriculture in successive governments since 2007 and controller of the powerful Rural Development Fund, began to emerge clearly from this moment onwards. At the extraordinary conference organised by the RNI just 20 days after the 2016 elections, Akhannouch was voted in as the leader of the party, willing to devote himself to the task of restructuring to mould it into the alternative to the governing party. Although the RNI’s results in the 2016 legislative elections had been modest, with only 37 seats out of a total of 395, taking fourth place by number of seats, its role was decisive in preventing the formation of a government led by Benkirane in coalition with the Istiqlal Party, then led by the populist Hamid Chabat.

The RNI had played the role of kingmaking party for decades, having formed part of almost all governments since the 1977 legislative elections. In 2016 the RNI agreed to join the government on two conditions: the exclusion of Istiqlal and the inclusion of the Socialist Union of Popular Forces (USFP), which in turn led the withdrawal of Benkirane and his replacement by Saadeddine Othmani, the man of concessions who has now ended up leading the PJD to its resounding defeat.

One special feature of the 2021 elections is that they coincided with the holding of municipal and regional elections that are scheduled every six years. The aim was to ensure a higher turnout, given that the municipal elections have always recorded higher levels of voting than the legislative elections.

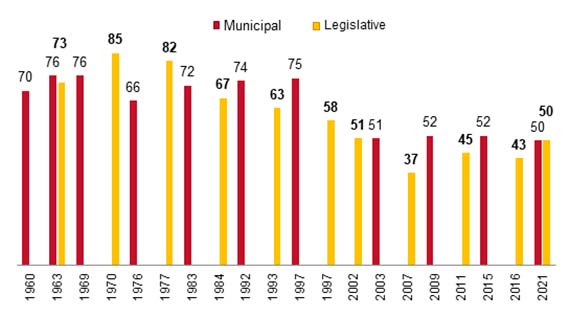

The turnouts over the course of Moroccan electoral history fall into two distinct periods: Hassan II’s reign, with very high voting percentages in both types of election, and the current monarch’s reign, where the turnout figures become more credible, hovering at around 50% in the municipal elections and below this threshold in the legislative elections, with a minimum in 2007 falling as low as 37%. In the previous legislative elections in 2016, turnout reached 43%. Exceeding this figure therefore constituted something of a challenge.

The concurrence of the two elections in 2021 ensured that the final turnout was 50.18% of the electorate, something that was triumphally announced to the media as though it were a democratic success. But this figure is an average derived from the higher turnout in rural and desert areas (as on previous occasions, the turnout figures for Saharan provinces such as El Aaiun-Saguia al Hamra, at 66.9%, have again been presented to the public as confirmation of the ‘Moroccanness’ of their inhabitants) and the much lower participation in urban areas such as Casablanca, where turnout in the Al Fida-Mers Sultán constituency, according to Medias 24, was only 19.8%. The delay in publishing the data broken down by party and by constituency prevents a more detailed analysis for the time being. Another figure that the Moroccan authorities often prefer to sweep under the carpet is the number of spoiled ballots, which in urban constituencies such as Casablanca can, according to some estimates, be as high as 25%, a phenomenon that may be interpreted as a protest vote.

These multiple elections have had a feature of additional interest, as the geographer and expert in Moroccan elections David Goeury has pointed out, namely that voters decided the political architecture of the country in one go (parliament, town halls and regional chambers), with votes cast in the legislative elections being influenced by voters’ perceptions, positive or negative, shaped by parties in their most immediate vicinity, the municipality.

This may be one of the explanations accounting for the enormous swing in the legislative election results, where the party that had hitherto led the governing coalition, the Islamist PJD, plummeted from 125 seats to just 13. Its record in charge of the town halls of the country’s largest cities (Casablanca, Fez, Tangier, Kenitra and Agadir) was controversial and patchy, and was harshly punished by the electorate. Other factors too undoubtedly contributed to the setback, however. Of the 13 seats that the party managed to win, only four were secured from the constituency lists and courtesy of the modification to the way the electoral quota was calculated, which it had opposed so fiercely, while another nine derived from the regional lists reserved for women candidates.

The electoral context

It is impossible to divorce the result from the context in which the elections were held. Employment and the economy were severely affected by a year and a half of pandemic, with a 7% fall in GDP in 2020, and scant recovery so far in 2021, despite a good year for agriculture.2 All this has taken a heavy toll, although from the healthcare perspective Morocco has achieved a notable level of vaccination, outperforming other countries in the region. But the isolation that the country has endured throughout this period, with its borders sealed, has had consequences in terms of declining tourism, including the return of over 3 million Moroccans living abroad –who surprisingly sent more money home in remittances, up by 45% on the year before–,3 contributing to increases in the rates of poverty and vulnerability.

On the international stage, Morocco received a notable fillip when the US President, Donald Trump, announced he was recognising Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara in December 2020, as a quid pro quo for Morocco signing up to the Abraham Accords with the establishment of full relations with Israel. The latter may have had a certain impact on the PJD’s election results, given that some of its supporters were disapproving of the shift. The tension between the Unity and Reform Movement (MUR), the ideological progenitor of the PJD and the source of its grassroots support, and the leadership of the party, obliged at the head of the government to compromise on key issues for the movement (such as the teaching of scientific and technical subjects in French and the normalisation of relations with Israel), demotivated its rank and file and made it harder to find candidates for the municipal election. Whereas the PJD entered 16,310 candidates in the 2015 municipal elections (12.46%), in 2021 it entered only 8,681 (5.51%). Meanwhile, all the other parties increased their candidate numbers, especially the RNI, which rose from 14,617 to 25,492, something that would undoubtedly impinge on the PJD’s results: 5,021 councillors elected in 2015 as opposed to 777 in 2021.

Figure 2. Candidates running in the municipal elections, 2015-21

| 2015 | 2021 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Nº | % | Nº | % |

| PAM | 18.227 | 13,92 | 21.187 | 13,45 |

| Istiqlal | 17.214 | 13,15 | 19.845 | 12,59 |

| PJD | 16.310 | 12,46 | 8.681 | 5,51 |

| RNI | 14.617 | 11,16 | 25.492 | 16,18 |

| USFP | 11.685 | 8,92 | 12.945 | 7,76 |

| MP | 10.767 | 8,22 | 12.221 | 7,76 |

| PPS | 9.675 | 7,39 | 9.815 | 6,23 |

| UC | 7.923 | 6,05 | 8.713 | 5,53 |

| FGD | 3.970 | 3,03 | 3.543 | 2,25 |

| FFD | 3.426 | 2,62 | 3.858 | 2,45 |

Source: the authors based on the Moroccan Interior Ministry’s election website, www.elections.ma.

Disaffection among the PJD rank and file became evident over the course of the legislative term. Publications such as the Al Akhbar newspaper in October 2020 and in August 2021 hespress.com, the most widely-read news website in Morocco, published figures showing the desertion the Islamist party was suffering among local and regional representatives in provinces such as Marrakech, Rabat and Fez. The PJD was not the only party affected by this phenomenon, and indeed in the year preceding the election there was an atypical number of defections recorded among local political representatives compared with the two previous elections. Such defections affected virtually all the parties and went in all directions, although the greatest beneficiary was the RNI, already perceived as a future winner.4

It was now evident that there was an official desire to remove the PJD from the government by placing it in awkward situations and forcing it to take a stance on such issues as the legalisation of cannabis cultivation for therapeutic purposes, supported by the PAM, and the application of a controversial temporary hiring system in the public sector, especially involving teachers and doctors, to meet the guidelines of international financial institutions. But the most striking example was Organic Law (04-21) relating to the House of Representatives proposed by the Interior Ministry and endorsed by all political parties in parliament on 5 March 2021 with the exception of the Islamists of the PJD (the result was 162 votes in favour, 104 against and one abstention of the Federation of the Democratic Left).5 The new electoral law sought to make it more difficult for the winning party to obtain more than one seat per constituency, something that had provided the PJD an additional number of seats in 23 constituencies in 2016 (in Tangier it secured three out of four possible seats). According to the new reading of the electoral code, the proportional representation of the ‘greatest remainder’, which had been calculated on the basis of valid votes, would now be calculated on the basis of registered voters. This meant that the higher the electoral quotient the lower the possibility any party would have of achieving it, closing the door to the accumulation of seats by the winning party. The suppression of the 3% threshold in the new law opened the way to a greater fragmentation of parliament. Paradoxically, however, the new law has not had the effect that had been sought, except for the victorious party, which would have picked up some additional seats.

These elections had the highest number of registered voters in Morocco’s electoral history, at 17,983,490, which is 2,280,837 more than in the legislative elections in 2016. As is customary in the run-up to elections, the authorities used the electoral lists website (www.listeselectorales.ma) as a means of informing, and above all, encouraging the registration of the youngest citizens in order to catalyse electoral participation. However, the pyramid of voters shows an under-representation of young people aged 18-24. In the 2021 electoral census this age group accounted for 8% of voters according to the Interior Ministry, whereas in the forecast for 2021 released by the High Commission for Planning (HCP) they account for 17%, which means that around 2,800,000 were not included in the lists. At least 7 million Moroccans with the right to vote, in addition to those living abroad, remain missing from incomplete electoral lists thanks to the method of compilation, which is reliant on citizens’ voluntary registration.

The electoral campaign: the primacy of the virtual realm

The electoral campaign, which ran from 26 August to the day prior to the ballot, took place in an atypical atmosphere affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and its fallout. During the two weeks it lasted, the country was subjected to a nocturnal curfew beginning at 9pm, at a time when daily infections and deaths reached unprecedented numbers, exceeding 10,000 and 150, respectively. The possibility was even considered of postponing the election if the situation deteriorated, given that the population was more concerned about healthcare and above all the socio-economic situation than about politics.

In order to safeguard the electoral process, however, the government imposed drastic measures to contain the pandemic; these had the effect of diluting the election campaign, which previously would have had a much more visible presence on the country’s streets. After an initial ban and in response to the insistence of the political parties, the government ended up authorising the distribution of printed matter (leaflets, lists of candidates, manifestos, etc), canvassing in the streets by groups not exceeding 10 people and five vehicles, and the holding of rallies attended by no more than 25 people. Consequently, with very few exceptions, the political parties and their candidates decided to transfer a major part of their campaigns online. This was by no means an innovation, because in earlier elections (those of 2011, 2015 and 2016) virtual campaigns had already played a fundamental role among urban populations, which include the greatest consumers of new technology. Moreover, the most important social debates that have taken place in Morocco in the last decade have migrated, as in other countries with authoritarian or semi-authoritarian regimes, to the social media. It was there that in 2018 the most successful consumer boycott in terms of popular participation was organised against the Danone brand of yogurts, the Sidi Ali brand of bottled water and the Afriquia chain of petrol stations, owned by Aziz Akhannouch, ‘as an act of protest against the corruption and despotism of the large corporations that participate in the impoverishment of the people’.

As soon as the election campaign got under way social media were rapidly inundated by party political adverts and candidates’ photos. According to the sociologist Said Bennis, most political parties’ virtual campaigns used outdated tools and formats exhibiting scant creativity that were indistinguishable from campaigns in the street. The RNI’s campaign was the most creative however, and it was evidently run by professionals. It was based on brief and direct audio-visual messages and slogans. It relied on sponsored advertising in the social media to ensure its image and rhetoric reached the great mass of voters. Meanwhile, the online realm enabled the few political voices calling for a boycott, the leftist An-nahj Ad-dimuqrati party and the Justice and Spirituality Islamist association, to run their own campaign unmolested by the authorities.

Virtual campaigning did not, however, reach the entire electorate or all generations, and the political parties were obliged to take a more in-person approach to the rural population and more marginalised districts. It was in these areas that the majority of complaints about the widespread use of money to secure votes were recorded, lodged particularly by the PJD, the Party of Progress and Socialism (PPS) and the Unified Socialist Party (PSU).Figure 3. The results of the threefold election, 2021 and 2015-16

| Moroccan election results 2021 | Moroccan election results 2015-16 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Members of Parliament 2021 (1) | Councillors 2021 | Regional councillors 2021 | Members of Parliament 2016 (2) | Councillors 2015 | Regional councillors 2015 |

| RNI | 102 | 9.995 | 196 | 37 | 4.408 | 90 |

| PAM | 96 | 6.210 | 143 | 102 | 6.655 | 135 |

| Istiqlal | 81 | 5.600 | 144 | 46 | 5.106 | 119 |

| USFP | 35 | 2.415 | 48 | 20 | 2.656 | 46 |

| MP | 29 | 2.253 | 47 | 27 | 3.007 | 58 |

| UC | 18 | 1.626 | 30 | 19 | 1.489 | 27 |

| PJD | 13 | 777 | 18 | 125 | 5.021 | 173 |

| PPS | 22 | 1.532 | 29 | 12 | 1.766 | 23 |

(1) The MDS won three seats, the FFD three and the FGU and the PSU one each.

(2) The MDS won three seats, the FFD two and the PGVM and the PUD one each.

Source: the authors based on the Interior Ministry’s election website, www.elections.ma.

The threefold elections of 2021 enabled a broad correspondence to emerge in the overall results of the three institutional spheres concerned, demonstrating the dominance of the RNI in all three, followed by the PAM and Istiqlal, to make up a trio of parties that stand out from the other political groupings. They were followed, in a second tier, by the USFP and the Popular Movement (MP), and in a third tier by the Constitutional Union (UC), the PPS and the PJD, reduced to a rump with a symbolic representation like the one it obtained in its first legislative term in the parliament of 1997-2002.

The delay, now chronic, in publishing the results broken down by parties, constituencies and regions prevents a more detailed analysis of the results from being conducted for now. At the time of writing this paper almost two weeks after the elections were held, the total votes received by the parties at the national level, the number of abstentions by constituency and the spoilt ballots at the various levels –a significant number given the way they have increased since independence– remain unknown.

As on previous occasions, the elections were monitored by 70 observers belonging to 17 international organisations and a total of 7,120 national observers: 4,500 accredited by the National Human Rights Council (CNDH) and 2,620 by a network of 23 associations.

All of them highlighted the example set by Morocco in terms of the peaceful handover of power, respecting the verdict of the ballot box. On election night itself, having learned of the provisional results, Othmani, Secretary General of the PJD, congratulated the Secretary General of the RNI on its victory before tending his resignation and that of other members of his party’s general secretariat in the wake their defeat, in another new development in the country’s political practice.

Whereas the statement released by the outgoing Secretary General alleged ‘serious incidents’ recorded in the electoral colleges, critical voices within the PJD, like that of Amina Maa El Aynain, sought to explain the electoral debacle in terms of the deterioration in the party’s image from the time Othmani was appointed head of the government and his election as the new Secretary General of the PJD, placing an especial emphasis on the way in which he ‘sidelined’ his predecessor Abdelillah Benkirane, one of the most charismatic and popular leaders among the rank and file of the party and the country in general.

It is clear that the party in government over the course of the last decade suffered a severe electoral backlash for pursuing unpopular policies, especially in regard to temporary employment contracts, the suppression of the Compensation Fund, the rise in the retirement age and the wage cuts that led to a fall in the purchasing power of wide swathes of the population, especially during the pandemic. Also pertinent in this regard are the remarks made by Reda Dalil, leader writer at the French-language weekly publication TelQuel, about the PJD’s incompetence in managing the cities it governed, its impotence vis-à-vis the royal palace, its ineptitude when it came to moralising about public life, even the hypocrisy in terms of the conduct of its representatives and the concessions it has had to make in its 10 years in government. Taken together this all served as a breeding ground for detractors within and outside the PJD when it came to finding a culprit for the country’s predicament.

Prospects for the formation of the government

After learning of the RNI’s victory, King Mohammed VI gave the task of forming a new government to its leader Aziz Akhannouch, who immediately entered into talks with other parties. The options available to him for building a stable majority (the absolute majority is 198 seats) range from an alliance between the three victorious parties, which would total 269 seats, or an alternative alliance with one or the other of the winning trio. The political scientist Mustapha Sehimi, who has been one of the greatest experts in electoral matters since 1976, sees the entry of the Istiqlal party into the government as more plausible, given the moderate image its leader Nizar Baraka has bestowed upon it, along with the USFP, its former partner in the Kutla Dimuqratia (the bloc that made up the nucleus of the alternating government between 1998 and 2002), and which remained in government until 2011. It would thereby amass 218 seats, a comfortable majority to which it might be possible to add the MP, strong among rural areas and the Amazigh, thereby totalling 247 seats. Such an alliance, argues Sehimi, would go down better with public opinion than the inclusion of the PAM in the government, a party with internal divisions (its leader, Abdellatif Ouahbi, who campaigned against the RNI, was undermined after the elections by a section of the party interested in joining the government), whose image as a party moulded by the administration and the royal palace works against it.

On 17 September the PAM national committee accepted Akhannouch’s invitation to join the governing coalition, forcing Istiqlal to bring forward the meeting of its leadership, which it had planned for 25 September, giving carte blanche to Nizar Baraka to negotiate its admission into the executive. If a government comprising the three large winning parties is formed, the problem would arise of distributing posts in an executive that is unlikely to be gung-ho in the prevailing circumstances and in which the RNI will try to control the ministries that are key to the economy. The opposition will be in the hands of a greatly weakened PJD, while the other parties in the parliamentary spectrum (the MP, USFP and UC), accustomed to always acting as bit players in the government, will be relegated to a secondary role. There may be one exception: the PPS, which in recent years has been a loyal ally in PJD governments and will face the dilemma of whether it should swell the opposition ranks.

The opening of parliament, due to take place on 8 October, obliges the formation of the government to be speeded up, although acceptance by the possible partners is subject to approval from their respective national committees. It would be an achievement for Akhannouch to have a government in place before the new legislature opens, avoiding the months of instability and uncertainty that marked the forming of earlier governments by Abderrahmane Youssoufi in 1998, Abdelillah Benkirane in 2011-12 and Saadeddine Othmani in 2016.

Conclusiones

The RNI party emerged as the clear winner in the threefold elections held in Morocco on 8 September. Its wide margin of victory heralds a new political architecture which will preside over the country for the five years that the forthcoming legislative term lasts. This period will lay the foundations for the ‘new development model’, designed to last until 2035. This model, promoted by the royal palace and unveiled last April, is likely to form the basis of the economic programme of the government that emerges from the recent legislative elections.

Bernabé López García

Honorary Chair of Arab and Islamic Studies at the Autonomous University of Madrid and codirector of the International Mediterranean Studies Workshop (TEIM)

Said Kirhlani

Doctorate in Arab and Islamic Studies and lecturer-researcher at the King Juan Carlos University | @saidkirhlani

1 See ‘Le nouveau Modèle de développement: Rapport Général’, Commission Spéciale sur le Modèle de Développement, April 2021.

2 Government finances recorded a budget deficit of DH40.6 billion at the end of August 2021, according to L’Economiste, ‘Le déficit budgétaire à 40,6 milliards de DH à fin Août’, 13/IX/2021.

3 See ‘Explosion des transferts de MRE en 2021 (+45% à fin Juillet)’, Media 24, 1/IX/2021; ‘Hausse spectaculaire des transferts de la diaspora marocaine (MRE)’, Financial Afrik, 3/VII/2021.

4 Abdelali El Hourri (2021), ‘Vague de démissions au Parlement: un reflet du mercato politique’, Medias 24, 7/IX/2021.

5 Lahcen Bensassi (2021), Las leyes electorales que marcan las citas electorales de 2021 con las nuevas reformas (القوانين الانتخابية المؤطرة لاستحقاقات 2021 مع التعديلات الأخيرة ), Rabat, Ar-risala.

6 Jaouad Bennis & Abdelhadi Samadi (Eds) (2021), Boycott, réseaux sociaux et communication de crise au Maroc, Force Equipement, Rabat.

Morocco’s Parliament building in Rabat. Photo: Pedro (CC BY 2.0)